My Reflection #1

advertisement

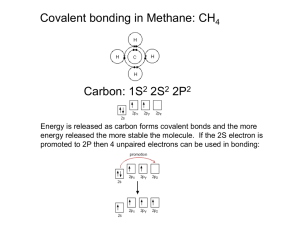

Miha Lee’s SLO Reflection #1 1 Misconception Report for Reflective Practice (High School Students’ Alternative Ideas about Chemical Bonding) BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF ASSIGNMENT The assignment is about high school students’ alternative ideas regarding chemical bonding. I reviewed a few research papers (Boo, 1998; Coll & Taylor, 2001; De Posada, 1997; Taber, 1995; Taber, 2000; Taber, 2003) in order to find out what students’ ideas about chemical bonding are “after” chemistry instructions and what they imply for chemistry education. First of all, I found the terms for students’ misunderstanding. They include: naive beliefs, preconceptions, alternative frameworks, children’s science, naive theories, naive conceptions, intuitive beliefs, intuitive science, learners’ science, and misconceptions. The term alternative conception is used to mean students’ ideas, manifested “after exposure to formal models or theories”, which are still at odds with those currently accepted by the scientific community. Especially, when an alternative conception is used with consistency over more than one context or event, it is referred to as an alternative framework. This investigation also revealed prevalent and consistent alternative conceptions about chemical bonding across a range of ages and cultural settings. Taber named those alternative conceptions as the Octet Framework because the most common and strong misconceptions have something to do with the octet rule. A majority of students believed that the main cause for chemical bonding was for atoms to obtain their full outer shells. The octet framework was created by chemistry instruction with the octet rule and Lewis model. The features of the octet framework were pursued and explained. Furthermore, I examined how the octet framework affects students’ ideas of chemical bonding. I provided a variety of exemplary misconceptions with respect to ionic bond, covalent bond, metallic bond, and intermolecular bond. The misconception of energy and reaction associated with chemical bonding was also explored. What caused the alternative conceptions was summarized. The most potent cause of the common misconceptions of high school students is the fact that the contents of chemical bonding in high school chemistry books heavily rely on such simple model as the octet rule. I suggested a few ways to fix the problem. Miha Lee’s SLO Reflection #1 2 CONNECTIONS TO THE SLO OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE In chemistry, chemical bonding is a fundamental conception that explains the behavior and change of matter. As a result, my teaching always begins with chemical bonding, but it seems difficult for my students to understand it because it is abstract. This is why I chose the topic chemical bonding for this assignment. When I read research articles for this assignment, I myself could make my pedagogical content knowledge about chemical bonding deeper enough to improve my teaching for my students. The cognitive theory in science education suggests that students’ prior knowledge provide the bedrock on which new ideas can be anchored for student learning. While appropriate conceptions can act as bridges (or stepping stones) to a new understanding, inappropriate conceptions can act as barriers. So, as a teacher I need to be familiar with and fully aware of students’ misconceptions so that I could help students move on from their alternative ideas to scientific ideas. This assignment assisted me to build up my pedagogical content knowledge that guides me to design my instruction to modify the misconceptions and promote conceptual understanding. The pedagogical skills that I learned to improve my students’ learning seem to be how to elicit students’ misconceptions and how to help my students confront with their misconceptions. REFLECTION What I learned from this assignment was that teachers’ convenient habits of thinking and talking are often taken by learners as absolute and literal meanings rather than being recognized as short-hand. Therefore, we should give heed to the use of such simple model as the octet rule when we teach chemical bonding. We should try to introduce my aspects of chemical bonding as a theory to explain matter’s properties. When we teach science, we present curriculum models that are designed to be matched to the level of complexity and abstraction that students can most benefit from. The optimum level of simplification is simple enough to allow students to understand and learn about the topic, yet also rigorous enough to provide a basis for students to develop further more advanced models later in their studies. Then, what should I do in order to prevent students from having these misconceptions from my instruction and help students develop more sophisticated and scientifically valid ideas? Students’ misconceptions do not fall down unless science teaching Miha Lee’s SLO Reflection #1 3 permits constructions of reasonable and accessible another ideas. This cannot happen by means of a single operation: students must be conscious of their misconceptions, ideas must be confronted, students must take on new models accessible to their minds (Strike & Posner, 1992); and finally, students must learn to distinguish the context (macroscopic vs. microscopic) in which different conceptual schemes can be applied (diSessa, 1993). Thus, I will make a number of changes in my instruction of chemical bonding: • introduce the driving force of chemical bonding and reaction. Chemists view the driving force for all chemical bonding and reactions as the decrease in energy of the system or the increase in entropy of the universe (Boo, 1998; Taber, 2003). For this reason all elements except the noble gas exist in states chemically bonded, not isolated, because they are energetically stable in those states; • introduce a general notion of bonding based on electrostatic interactions, before exploring specific bond types in detail. • emphasize bonding as the interactions that hold structures together rather than being related to developing full shells. • consider changing the order of teaching about bonding types to avoid inappropriate specific aspects of one model being transferred to others. It has been suggested that complexity increases from metallic, to ionic, to giant covalent, to simple covalent structures (Taber, 2003); • take time when introducing the “sea of electrons” notion to explore the metaphor so that learners can use it as the basis for a scientifically appropriate model. When we teach science using metaphors and analogies, we need to check the cartography of learner’s cognition before dropping an Ausubelian anchor such as the sea of electrons metaphor so that learners make the intended sense of them and are not left to guess what the relevance is (Taber, 2003); • introduce a general notion of bonding based on orbital theory. High school student learn orbital and electronic configuration of atoms, so they need to know that when atoms “overlap” their atomic orbitals, they form molecular orbitals that consist of chemical bonding. In summary, I learned the value of studies that explore learners’ changes in thinking in depth. So, I will go further to identify alternative conceptions or preferred mental models in other topics. What’s more, I will devise ways of teaching in which students can develop and change their mental models so that they can bring them closer to scientific understanding.