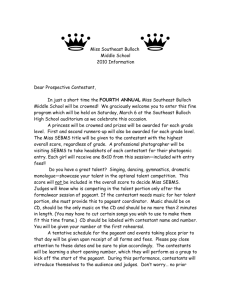

The Miss America Organization is the world`s

advertisement