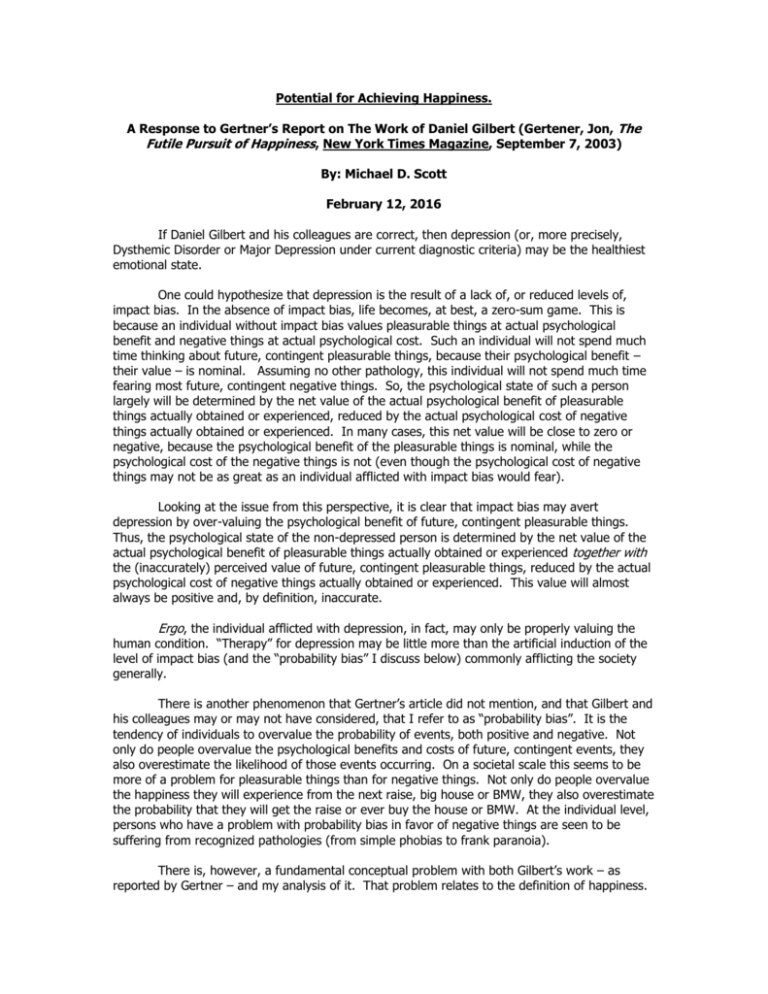

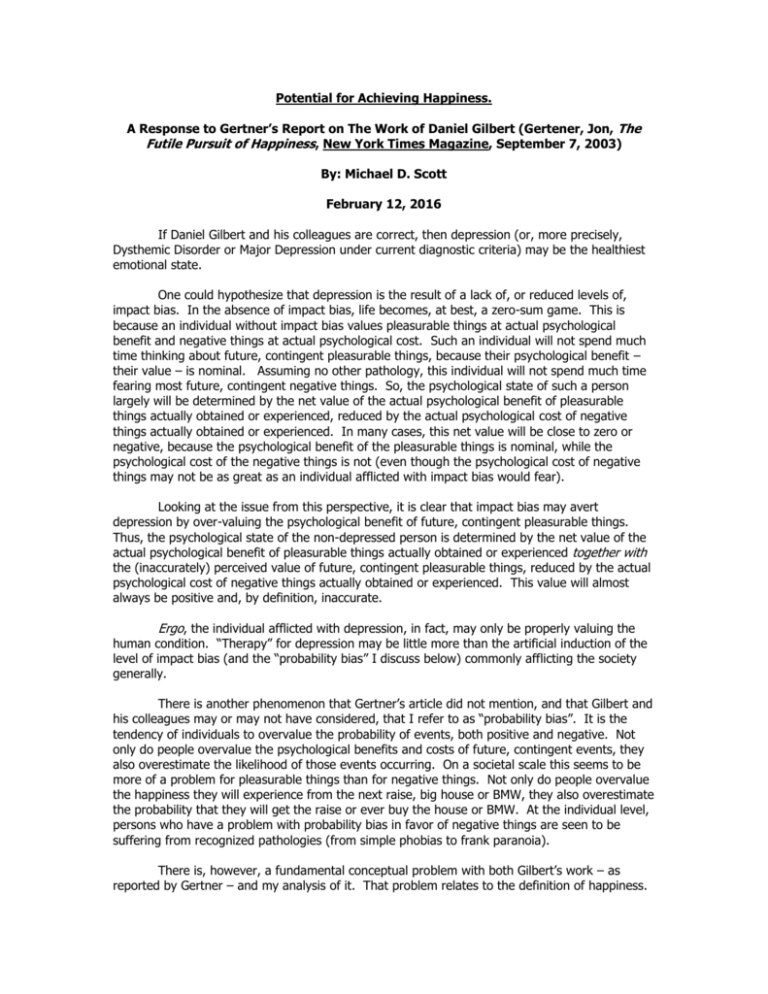

Potential for Achieving Happiness.

A Response to Gertner’s Report on The Work of Daniel Gilbert (Gertener, Jon, The

Futile Pursuit of Happiness, New York Times Magazine, September 7, 2003)

By: Michael D. Scott

February 12, 2016

If Daniel Gilbert and his colleagues are correct, then depression (or, more precisely,

Dysthemic Disorder or Major Depression under current diagnostic criteria) may be the healthiest

emotional state.

One could hypothesize that depression is the result of a lack of, or reduced levels of,

impact bias. In the absence of impact bias, life becomes, at best, a zero-sum game. This is

because an individual without impact bias values pleasurable things at actual psychological

benefit and negative things at actual psychological cost. Such an individual will not spend much

time thinking about future, contingent pleasurable things, because their psychological benefit –

their value – is nominal. Assuming no other pathology, this individual will not spend much time

fearing most future, contingent negative things. So, the psychological state of such a person

largely will be determined by the net value of the actual psychological benefit of pleasurable

things actually obtained or experienced, reduced by the actual psychological cost of negative

things actually obtained or experienced. In many cases, this net value will be close to zero or

negative, because the psychological benefit of the pleasurable things is nominal, while the

psychological cost of the negative things is not (even though the psychological cost of negative

things may not be as great as an individual afflicted with impact bias would fear).

Looking at the issue from this perspective, it is clear that impact bias may avert

depression by over-valuing the psychological benefit of future, contingent pleasurable things.

Thus, the psychological state of the non-depressed person is determined by the net value of the

actual psychological benefit of pleasurable things actually obtained or experienced together with

the (inaccurately) perceived value of future, contingent pleasurable things, reduced by the actual

psychological cost of negative things actually obtained or experienced. This value will almost

always be positive and, by definition, inaccurate.

Ergo, the individual afflicted with depression, in fact, may only be properly valuing the

human condition. “Therapy” for depression may be little more than the artificial induction of the

level of impact bias (and the “probability bias” I discuss below) commonly afflicting the society

generally.

There is another phenomenon that Gertner’s article did not mention, and that Gilbert and

his colleagues may or may not have considered, that I refer to as “probability bias”. It is the

tendency of individuals to overvalue the probability of events, both positive and negative. Not

only do people overvalue the psychological benefits and costs of future, contingent events, they

also overestimate the likelihood of those events occurring. On a societal scale this seems to be

more of a problem for pleasurable things than for negative things. Not only do people overvalue

the happiness they will experience from the next raise, big house or BMW, they also overestimate

the probability that they will get the raise or ever buy the house or BMW. At the individual level,

persons who have a problem with probability bias in favor of negative things are seen to be

suffering from recognized pathologies (from simple phobias to frank paranoia).

There is, however, a fundamental conceptual problem with both Gilbert’s work – as

reported by Gertner – and my analysis of it. That problem relates to the definition of happiness.

Unfortunately, this raises issues – either philosophic or theological – on which there is no

fundamental agreement in the scientific community. Philosophically, it seems that the Gilbert

work has focused to a significant extent on materialistic pleasures (although admittedly some of

the work has involved interpersonal relationships and other non-materialistic goods). A definition

of happiness may be inaccurate to the extent it is rooted in the empirical, materialist traditions of

John Locke and David Hume. The issue can also be approached theologically with the same

result. In short, there are philosophical and theological approaches to happiness that are more

sophisticated than those Gilbert seems to have looked at. Viewing “happiness” in terms of

personal peace, achievement of goods for the benefit of others, or maximizing life’s potential

other than in material terms makes true happiness both achievable and worth achieving.

2003 – Michael D. Scott. All Rights Reserved.