Arthritis Research & Therapy Vol 6 Suppl 2 Yocum Review Effective

advertisement

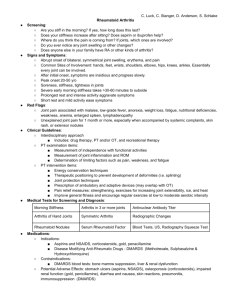

Arthritis Research & Therapy Vol 6 Suppl 2 Yocum Review Effective use of TNF antagonists David Yocum University of Arizona Arthritis Center, Tucson, AZ, USA Corresponding author: David Yocum (e-mail: yocum@u.arizona.edu) Received: 17 Jul 2003 Accepted: 6 Aug 2003 Published: 21 Jun 2004 Arthritis Res Ther 2004, 6(Suppl 2):S24-S30 (DOI 10.1186/ar997) © 2004 BioMed Central Ltd (Print ISSN 1478-6354; Online ISSN 1478-6362) Abstract Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists are biologic response modifiers that have significantly improved functional outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA is a progressive disease in which structural joint damage can continue to develop even in the face of symptomatic relief. Before the introduction of biologic agents, the management of RA involved the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) early in the course of disease. This focus on early treatment, combined with the availability of the anti-TNF agents, has contributed to a shift in treatment paradigms favoring the early and timely use of DMARDs with biologic therapies. Improvement in symptom control does not always equate to a reduction in disease progression or disability. With the emergence of structurerelated outcome measures as the primary means for assessing the effectiveness of antirheumatic agents, the regular use of X-rays is recommended for the continued monitoring and evaluation of patients. In addition to the control of symptoms and improvement in physical function, a reduction in erosions and joint-space narrowing should be considered among the goals of therapy, leading to a better quality of life. Adherence to therapy is an important element in optimizing outcomes. Durability of therapy with anti-TNF agents as reported from clinical trials can also be achieved in the clinical setting. Concomitant methotrexate therapy might be important in maintaining TNF antagonist therapy in the long term. Overall, the TNF antagonists have led to improvements in clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients with RA, especially those who have failed to show a complete response to methotrexate. Keywords: etanercept, infliximab, rheumatoid arthritis Introduction Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease that affects approximately 1% of the world’s population. It is characterized by a loss in functional capacity resulting from decreased structural integrity of the joints, diminished muscle strength and tone, and a variety of psychosocial factors. A 10-year outcomes study of 183 patients with early RA showed that most (94%) are able to manage daily life activities. On the basis of disability scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), a self-reported measure of functional impairment, 20% of patients had no disability, 28% were mildly disabled, and 10% were seriously disabled [1]. Treatment strategies have traditionally involved the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic agents (DMARDs) and, S24 more recently, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists. To optimize the functional outcomes of patients with RA, it is essential to examine the role of these newer agents in preventing disease progression and, potentially, in producing a cure. This examination requires several considerations, including (1) the importance of treating patients early, (2) the fact that improvements in symptom control do not necessarily signal reduced disease progression and disability, (3) the emergence of structurerelated parameters as a primary means of assessing response to therapy, (4) therapeutic alternatives for patients who do not respond satisfactorily to one anti-TNF agent, and (5) discontinuation rates and whether they influence therapy, given the desire for durable clinical responses. ACR = American College of Rheumatology; AE = adverse event; ATTRACT = Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy; CI = confidence interval; DMARDs = disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; ERA = Early Rheumatoid Arthritis; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; NSAID = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RA = rheumatoid arthritis; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. * * Delayed treatment Early treatment Available online http://arthritis-research.com/content/6/S2/S24 Table 1 Figure 1 12 14 Improved symptom control with disease progression 8 10 Score Parameter Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Outcome 4 6 0 2 0 6 12 18 24 Months Study of delayed and early treatment on disease outcome in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis (RA). *P<0.05 compared with the delayed-treatment group. Adapted, with permission, from Excerpta Medica [2]. The importance of treating patients early more timely use of DMARDs [4] and biologic therapy [5,6]. A panel of rheumatic disease experts has issued a consensus report addressing the role of TNF antagonists in patients with RA; the panel stated that TNF antagonists may become first-line agents in the treatment of RA and should not be reserved for patients with advanced disease [6]. Improvements in symptom control do not necessarily signal reduced disease progression and disability A study by Wolfe investigated the relationship between HAQ disability scores and the clinical course of RA in One nonrandomized, comparative study of pre-biologic 1843 patients [7]. Analysis of 1-year, 2-year, and therapies (namely standard DMARDs) compared the 3-year effects of delayed and early treatment on disease outcome in 206 patients with probable or definite recentonset RA as defined by the 1958 and 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, respectively [2,3]. The delayed treatment group (n=109) received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) followed by the administration of standard DMARDs – chloroquine or salazopyrine – at a mean of 123 days after diagnosis. The early treatment group (n=97) received NSAIDs with standard DMARDs at a mean of 15 days after the diagnosis (Fig.1) [2]. Results at 2 years indicated less radiographically evident joint destruction in the early-treatment group than in the delayed-treatment group (median Sharp scores: 3.5 versus 10; P<0.05). Thus, even with non-biologic therapies, a delay in therapy resulted in poorer outcomes. The advantages of the early initiation of therapy combined with the introduction of newer antirheumatic agents (such as the TNF biologic response modifiers) have shifted treatment models toward the earlier and Mean SJC 5.2 3.5 2.4 Redu ced sympt oms Mean TJC 13.7 9.0 6.5 Redu ced sympt oms Mean pain 22.4 13.4 11.1 Redu ced sympt oms Mean Larse n 5.6 12.3 16.9 Incre ased struct ural ind ex da ma ge SJC, swoll en joint count (maximum score 44); TJC, tender joint count (maximum score 53). Data on file, Centocor, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA. Sharp score data from this study indicates that HAQ disability scores might increase gradually with significant increases in structural damage, as assessed by Larsen index scores (data on file, Centocor, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA) (Table 1). There might also be a discrepancy between disease course and the presence of clinical indicators of disease such as pain, swollen joint count, and tender joint count. Wolfe and Sharp compared clinical disease assessment and radiographic progression in 256 patients with RA who were seen within 2 years of disease onset and were followed for up to 19 years [8]. On the basis of Sharp scores, joint-space narrowing, and erosion scores, it was concluded that RA progresses at a constant, linear rate that is neither greater in early RA nor reduced later in the course of disease (Fig.2), and that other factors (such as mean erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], mean grip strength, rheumatoid factor positivity, and swollen joint count) serve as independent predictors of radiographically evident joint destruction [8]. The emergence of structure-related parameters as a primary means of assessing response to therapy The 2002 ACR Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis state that the ultimate goals of RA management are the prevention or control of joint damage, the prevention of loss of function, and the amelioration of pain [5]. Kirwan described a potential pathogenic pathway for RA that supports these principles, showing a possible correlation between clinical symptoms and X-ray changes in RA (Fig.3) [9]. As assessment of structural damage in RA is emerging as an important method of evaluating disease outcomes, radiographs (that is, X-rays), have become essential tools not just for the diagnosis of RA but for continued monitoring. Radiographic findings can be reported with the Sharp score or the Larsen index. The total Sharp score is derived from the combination of erosion and joint-space narrowing S25 Arthritis Research & Therapy Vol 6 Suppl 2 Yocum Initiating eventInitiat ing event Figure 3 Sharp score JSN score JE score Figure 2 100 80 Structural damage progressi on Synovitis PannusSynovitis Pannus 60 4 0 Pain andClinica stiffne l ssPain symptom and s stiffne ss 2 0 0 0 Disease duration (years) 5 0 5 0 1 1 2 1 2X-ray changes Figure 4 Change in Sharp scores, joint-space narrowing (JSN), and joint erosion (JE) scores showing that rheumatoid arthritis progresses at a constant, linear rate. Adapted, with permission, from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [8]. 5 Swellin gSwelli ng Joint-spa ce narrowing Joint-spa ce narrowing Joint erosio nsJoin t erosio ns Potential pathogenic pathway for rheumatoid arthritis, supporting–0. 5 a relationship between structural damage and clinical symptoms. Adapted, with permission, from Excerpta Medica [9]. 4.00.0 0.50.5 4 3 2 1 0 –1 scores. Joint-space narrowing is not a major contributor to the overall Larsen index score [10]. –2 P value vs MTX <0.001 The Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (ERA) trial compared the efficacy of etanercept and methotrexate in 632 patients with early RA [14,15]. This trial consisted of a 1-year blinded phase [14] and a 1-year open-label extension phase [15]. Results at 2 years showed a significantly decreased incidence of structural joint disease in the etanercept-treated patients, as determined by changes in Sharp score (P=0.001) and erosion score (P=0.001); however, there was no statistically significant difference in joint-space narrowing scores (Fig.5) [15]. These two trials show how TNF antagonists have raised the standard of treating patients with RA on the basis of their shown ability to produce significant improvements in clinical parameters (such as ACR response) and to retard the radiographically assessed progression of joint damage. <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 Data from the ATTRACT (Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis With Concomitant Therapy) study showing the superiority of infliximab plus methotrexate (MTX) over methotrexate alone, as determined by the median change in the modified Sharp score. Data from [12]. Both Sharp and Larsen scores have been used to report outcome assessment data in clinical trials of TNF antagonists. The Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis With Concomitant Therapy (ATTRACT) was a 2-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that showed that the TNF antagonist infliximab, in combination with methotrexate, was superior to methotrexate alone in improving the radiographic outcomes of patients with RA [11–13]. At the 52-week endpoint, the infliximab-treated patients showed improvements in erosion, joint-space narrowing, and Sharp scores (Fig.4) [12]. S26 Although radiographic evidence of disease progression is frequently assessed by Sharp scores, clinical data are usually assessed by ACR criteria, such as the ACR20. Achievement of an ACR20 response indicates a greater MTX + placebo (n = 63) 3 mg/kg q 8 wk 3 mg/kg q 4 wk 10 mg/kg q 8 wk (n = 71) (n = 71) (n = 77) 10 mg/kg q 4 wk (n = 66) than 20% improvement in tender and swollen joint counts and at least three of the following disease activity variables: the patient’s assessment of pain, the patient’s global assessment of disease activity, the physician’s global assessment of disease activity, the patient’s assessment of physical function, and the ESR or the C-reactive protein level [5,16]. However, failure to achieve an ACR20 response should not necessarily be interpreted as a failure of therapy. Preliminary subgroup analysis data from the ATTRACT study indicate that in patients who failed to achieve an ACR20 response (that is, non-responders), those treated with infliximab and methotrexate showed a greater improvement in ACR20 response than the patients treated with methotrexate alone (Fig.6) (data on file, Centocor, Inc.). Thus, the regular use of Methotrexate 20 mg Etanercept 25 mg Figu re 5 Available online http://arthritis-research.com/content/6/S2/S24 Figure 6 ACR 20 Responders ACR 20 Non-Responders * ** n =34 *N=40 N=25 N=31 n =38 n =10n =33 n =32 n =38 n =28n =40 n =25 n =31 3.5 3.2 -1.7 -2.0* * 5.0 3.6 1.9 3.0 1.3 0.7* 0.7 2.5 2.0 1.5 4.3 4.0 1 . 2 2.5 1.3 0.5* 3.0 0.5 2.0 1.3* 0.0 1.0 1.0 0.0 0.5 0. 0 * P = 0.001 1 . 2 -1 .0 Total Sharp score Joint erosion Joint-space narrowi ng Data from the ERA (Early Rheumatoid Arthritis) trial showing the superiority of etanercept over methotrexate, as determined by improvements in erosion and Sharp scores, but not joint-space narrowing score at 2 years. Adapted, with permission, from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [15]. radiographic imaging, including X-rays, can be considered an important component of the overall assessment and evaluation of patients with RA. Therapeutic alternatives for patients who do not respond satisfactorily to one anti-TNF agent The failure of a patient to respond to a single TNF antagonist should not be taken to mean that the patient is refractory to all TNF antagonists. Studies have shown success with infliximab in patients who have failed to respond to etanercept therapy, and vice versa. In one study, investigators in community rheumatology practices documented the efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with an inadequate response to etanercept [17]. After four infusions of infliximab, patients experienced reductions in mean tender joint counts (57%), mean swollen joint counts (66%), ESR (20%), and mean daily prednisone requirement (38%) Methotrexate alone Infliximab 3 mg/kg q 8 wk + methotrexate Infliximab 3 mg/kg q 4 wk + methotrexate Infliximab 10 mg/kg q 8 wk + methotrexate Infliximab 10 mg/kg q 4 wk + methotrexate (Table 2) [17]. Although this study lacks the structure of a randomized controlled clinical trial, it provides preliminary data that TNF antagonist therapy should not be abandoned in the face of an apparent initial unsatisfactory response. Do discontinuation rates influence therapy? Discontinuation rates of a pharmacologic agent, including antirheumatic agents, can influence therapy. Discontinuation rates can serve as a reasonable guide to the efficacy or safety of an agent. Before definitive conclusions can be made, other variables should be considered, for example the phase of therapy (such as acute, continuation, maintenance), reasons for the discontinuation (such as lack of efficacy, toxicity, adverse events [AEs]), associated symptoms or intercurrent illness, and drug profile (including Prelim inary radiog raphic data from the ATTR ACT (Anti-T umor Necro sis Factor Trial in Rheu matoid Arthriti s With Conco mitant Thera py) study, indicat ing the superi ority of inflixi mab plus metho Table 2 Clinical changes after a switch from etanercept to infliximab Post-infliximab Pre-infliximab (4 doses; Parameter (baseline) week 14) Outcome Mean tender joints (n) 17.1 7.3 57% reduction Mean swollen joints (n) 11.2 3.8 66% reduction ESR (mm/h) 33 26.5 20% reduction Mean prednisone dosage 9.2 5.7 38% reduction (mg/day) ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Data from [17]. previous medications and concomitant therapy). Discontinuation rates can also serve as a reflection of the chronic, aggressive course of the disease, which can require more than one therapy or can sometimes involve the switching of agents to achieve satisfactory clinical outcomes. For a better understanding of how discontinuation rates affect therapy in the era of anti-TNF agents, a review of the discontinuation rates with DMARDs based on three large studies is presented [18–20]. According to a Markov model based on the Arthritis, Rheumatism, and Aging Median change from baseline (Sharp scores) Change in Sharp scores/2 years trexate over methotrexate alone in patients who did and did not S27 achieve an ACR20 (that is, ACR20 responders and non-responders). ACR20 is a more than 20% improvement in tender and swollen joint counts and at least three of the following disease activity variables: the patient’s assessment of pain, the patient’s global assessment of disease activity, the physician’s global assessment of disease activity, the patient’s assessment of physical function, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level. *P<0.05 versus placebo. Data on file, Centocor, Inc., Malvern, PA, USA. Arthritis Research & Therapy Vol 6 Suppl 2 Yocum Table 3 Discontinuation rates at 1 year for anti-TNF agents in randomized clinical trials No. of Trial patients Patient characteristics Regimens Discontinuation rates (%) ATTRACT [12] 428 Active RA despite methotrexate therapy; Infliximaba21 mean duration 9–12 years 3 mg q 4 weeks a3 mg q 8 weeks 10 mg q 4 weeks 10 mg q 8 weeks Placebo(weekly) 50 ERA [14] 632 Early RA; Etanercept mean duration <1 year (i.e. 11–12 months) 25 mg twice weekly 15 Methotrexate (mean, 19 mg) weekly 21 aAll groups also received methotrexate, mean 16–17 mg/week. ATTRACT, Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis With Concomitant Therapy; ERA, Early Rheumatoid Arthritis. S28 Medical Information System (ARAMIS) postmarketing surveillance cohort (n=4285 consecutively enrolled patients with RA who were followed up for 17,085 patient-years), 46–60% of patients initially receiving methotrexate alone would still be on methotrexate alone or with a DMARD after 5 years [20]. When patterns of drug use in patients with RA in a community setting were evaluated, drug discontinuation and medication switching were observed to be common [19]. Almost 20% (1300 of 6944) of patients who took at least one antirheumatic drug during the study year used a DMARD, with methotrexate being the most frequently used. Of the DMARD users, 23% discontinued the drug during the study year, 19% were taking other concurrent DMARDs, and 16% added another DMARD. DMARDs were often used with other (that is, non-DMARD) agents, because 63% of DMARD users were also taking an NSAID and 61% were taking a corticosteroid [19]. Aletaha and Smolen [18] evaluated the treatment patterns with traditional DMARDs and their changes during the two decades before the introduction of newer antirheumatic agents. The study involved 593 patients with RA who were followed from their first presentation in the clinic throughout the course of their disease, of whom 222 patients received their first DMARD during the study [18]. Before 1985 most (65–90%) of initial DMARDs were gold compounds, whereas after 1985 methotrexate was the initial DMARD in 29% of new patients. Patients with high disease activity were more likely to be receiving methotrexate than other DMARDs, and first DMARDs in new patients were used for longer than subsequent DMARDs, because they were more effective [18]. On the basis of an analysis of 122 controlled trials and observational studies involving 16,071 patients with RA, Hawley and Wolfe [21] concluded that good retention rates in studies lasting 3–12 months were not representative of long-term results, although the retention rates observed in controlled and observational studies were similar during the first treatment year. Discontinuation rates for anti-TNF agents as observed in two long-term, randomized RA trials, one involving infliximab (ATTRACT) and the other etanercept (ERA), are listed in Table 3 [12,14]. These trials differed in terms of study size (428 versus 632 patients), stage of RA (laterstage [active] versus early), and regimens (anti-TNF therapy plus a DMARD compared with placebo plus a DMARD [ATTRACT], versus anti-TNF monotherapy compared with a DMARD [ERA]). In the ATTRACT study, in which patients were randomized to receive 3 or 10mg of infliximab every 4 or 8 weeks, or placebo, with methotrexate given to all groups, 54-week data showed that discontinuation rates due to AEs were about 8% (26 of 340) in infliximab-treated patients compared with about 16% (7 of 44) of patients in the placebo-plus-methotrexate group [12]. The discontinuation rates due to lack of efficacy were about 12% (40 of 340) in the infliximab-treated patients compared with about 73% (32 of 44) in the placebo-plus-methotrexate group. In the ERA trial, in which patients were randomized to receive 10 or 25mg of etanercept twice weekly, or methotrexate weekly, discontinuation rates due to AEs or elevated aminotransferase levels were 6% for the group receiving 10mg of etanercept, 5% for the group receiving 25mg of etanercept (P<0.001 versus methotrexate), and 11% for the methotrexate group [14]. Lack of efficacy was the reason for discontinuation in 7% and 5% of patients in the groups receiving 10 and 25mg of etanercept, respectively, versus 4% in the methotrexate group [14]. The chronic course of RA merits long-term maintenance therapy. Efforts to lower discontinuation rates have included the administration of methotrexate together with anti-TNF agents. Support for enhanced therapeutic efficacy with this approach has been documented [22,23]. Maini and colleagues conducted a 26-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 101 patients with active RA exhibiting an incomplete response to methotrexate (about 9–15 mg per week for the last 3 months before the study) [22]. Patients received either infliximab 1, 3, or 10mg/kg intravenously with or without methotrexate 7.5mg per week, or placebo plus methotrexate 7.5mg per week intravenously at weeks 0, 2, 6, 10, and 14; follow-up continued until week 26 [22]. Results showed that when infliximab (at all dose regimens in the study) was administered together with infliximab and weekly methotrexate, 60–80% of patients attained a Paulus 20% response for up to 14 weeks, and 50–60% of patients sustained a response after the cessation of treatment until the end of the study [22]. In the ATTRACT study, the combination of infliximab and methotrexate over 30, 54, and 102 weeks provided significant, clinically relevant improvement in a majority of patients with RA who had an incomplete response to methotrexate alone; however, discontinuation rate data at 102 weeks have yet to be made available [11–13]. As more data from long-term trials that involve these agents accumulate, focusing on discontinuation rates and correlating safety and efficacy parameters, the role of concomitant methotrexate in the long-term maintenance of anti-TNF therapy will be clarified further. Aside from clinical trial data, clinical practice data report the discontinuation rates of anti-TNF agents. A 2-year Swedish study conducted in seven clinical centers evaluated the anti-TNF agents infliximab (n=135) and etanercept (n=166]) and a newer-generation DMARD, leflunomide (n=103), for efficacy (based on ACR response criteria) and tolerability (based on survival and AEs) in patients with RA [24]. Initial doses of the agents in this study were 3mg/kg intravenously at weeks 0, 2, 6, and 12 and every 8 weeks thereafter for infliximab, and 25mg subcutaneously twice weekly for etanercept; appropriate dose adjustments and switching to another of the three agents were allowed after withdrawal from one treatment [24]. On the basis of ACR20 and ACR50 responses, the TNF antagonists performed significantly better than the newer DMARD, and no significant differences were noted between the efficacy of infliximab and etanercept at 0.5, 1.5, 9, and 12 months [24]. At 3 months, ACR20 and ACR50 responses were noted in a greater percentage of patients who received infliximab than leflunomide (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively), whereas ACR20 and ACR50 responses were noted in a greater percentage of etanercept-treated and leflunomidetreated patients at 3 months (P<0.001) and 6 months (P<0.05) [24]. Survival data showed that 75%, 79%, and 22% of A v a i l a b l e patients continued to receive infliximab, etanercept, and leflunomide, respectively, after 20 months (for 24-month discontinuation rates of 25%, 21%, and 78%, respectively) [24]. In the infliximab-treated and etanercepttreated patients in this study, AEs were the primary cause of drug discontinuation. There were 2.8 life-threatening AEs per 100 treatment-years (namely anaphylactoid reaction, mesothelioma, and severe pharyngitis) and 10.0 o n l i n e h t t p : / / a r t h r i t i s r e s e a r c h . c o m / c o n t e n t / 6 / S 2 / S 2 4 serio us AEs per 100 treatment-years (namely allergic reactions, bacterial infections, Hodgkin’s/non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, thrombocytopenia, lupus-like reaction, discoid lupus) with infliximab. Etanercept-treated patients experienced 1.3 fatal AEs per 100 treatment-years (namely gastroenteritis, immunocytoma of the breast, and myocardial infarction) and 7.0 serious AEs per 100 treatment-years (namely myocardial infarction, bacterial infections, uterine cervical carcinoma, leukemia, malaise, leucopenia, Bell’s paralysis, cutaneous vasculitis, discoid lupus) [24]. An electronic medical record system was used to review all patients seen in a university rheumatology clinic (the Arizona Arthritis Center at the University of Arizona) who had been treated with infliximab (n=118) or etanercept (n=90) between February 1998 and May 2002 [25]. Data were collected on diagnosis, disease duration, dates of therapy, reasons for treatment discontinuation, and AEs and serious AEs. Most (82%) of the 208 patients in this study had a diagnosis of RA [25]. Kaplan–Meier analysis for the discontinuation of any anti-TNF therapy showed a mean medication duration of 768 days (95% confidence interval [CI] 693–843 days) with a maximum follow-up time of 1260 days [25]. For infliximab, the mean time to discontinuation was 931 days (95% CI 844–1018 days), with 32 (27%) of 118 patients discontinuing infliximab. After 15 months there was a 0% rate of discontinuation with infliximab [25]. For etanercept, the mean time to discontinuation was 595 days (95% CI 491–700 days), with 58 (64%) of 90 patients discontinuing etanercept [25]. The log-rank test coefficient for the difference between survival curves for the two groups was 20.03 (P<0.01) and the Gehan–Breslow coefficient was 16.01 (P<0.001) [25]. The investigators documented a low probability of discontinuations of infliximab after 1 year of treatment and concluded that, on the basis of the results of the survival analysis of the data from their practice, patients receiving infliximab remain on therapy significantly longer than those on etanercept [25]. Conclusion Clinical trials and community findings support the efficacy and safety of the current TNF antagonists. To optimize comprehensive therapeutic outcomes in clinical practice, DMARDs or anti-TNF agents, or both, should be instituted early, and patient status and response to therapy should be monitored on a regular basis by using X-rays and radiographic scores. Structure-related parameters are emerging as a most important measure of outcome by which the efficacy of antirheumatic therapies are evaluated. In addition to a reduction of symptoms and improvement in physical function, optimal reductions in erosions and joint-space narrowing should be part of the goals of therapy. Patients who show an unsatisfactory response to S29 S30 Arthritis Research & Therapy Vol 6 Suppl 2 Yocum one anti-TNF agent should be started on another. Adherence to therapy is an important element in optimizing outcomes, and durability of therapy can also be achieved in the clinical setting. Finally, the concomitant administration of methotrexate might be important in the maintenance of TNF antagonist therapy in the long term. Overall, the TNF antagonists have provided significant improvements in clinical and radiographic outcomes for patients with RA, especially those who have had an incomplete response to methotrexate therapy. Competing interests DY is, or has been, a speaker for Centocor, BoehringerIngelheim and Amgen, is a consultant for Centocor, Novartis and Boehringer-Ingelheim, and has received grants from Centocor, Amgen, Abbott, Medimmune, Alexion and Novartis. Acknowledgement The transcript of the World Class Debate for ACR 2002 has been published electronically in Joint and Bone. This article, and others published in this supplement, serve as a summary of the proceedings as well as a summary of other supportive, poignant research findings (not included in the World Class Debate ACR 2002). References 1. Lindqvist E, Saxne T, Geborek P, Eberhardt K: Ten year outcome in a cohort of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: health status, disease process, and damage. Ann Rheum Dis 2002, 61:1055-1059. 2. Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, vander Horst-Bruinsma IE, Zwinderman AH, Breedveld FC, Hazes JM: Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med 2001, 111:446-451. 3. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS: The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988, 31:315-324. 4. van der Heide A, Jacobs JWG, Bijlsma JWJ, Heurkens AHM, van Booma-Frankfort C, van der Veen MJ, Haanen HC, Hofman DM: The effectiveness of early treatment with ‘second-line’ antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996, 124:699-707. 5. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines: Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46: 328-346. 6. Wolfe F, Cush JJ, O’Dell JR, Kavanaugh A, Kremer JM, Lane NE, Moreland LW, Paulus HE, Pincus T, Russell AS, Wilskie KR: Consensus recommendations for the assessment and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001, 28:1423-1430. 7. Wolfe F: A reappraisal of HAQ disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43:2751-2761. 8. Wolfe F, Sharp JT: Radiographic outcome of recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a 19-year study of radiographic progression. Arthritis Rheum 1998, 41:1571-1582. 9. Kirwan JR: Systemic low-dose glucocorticoid treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2001, 27:389403. 10. Van Der Heijde D, Simon L, Smolen J, Strand V, Sharp J, Boers M, Breedveld F, Weisman M, Weinblatt M, Rau R, Lipsky P: How to report radiographic data in randomized clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis: guidelines from a roundtable discussion. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 47:215-218. 11. Maini R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F, Furst D, Kalden J, Weisman M, Smolen J, Emery P, Harriman G, Feldmann M, Lipsky P, for the ATTRACT Study Group: Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor aa monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant m et h ot re x at e: a ra n d o m is e d p h a s e III tr ia l. L a n c et 1 9 9 9, 3 5 4: 1 9 3 21 9 3 9. 12. Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DMFM , St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breed veld FC, Kalde n JR, Smole n JS, Weism an M, Emery P, Feldm ann M, Harrim an GR, Maini RN, for the Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis With Concomitant Therapy Study Group: Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000, 343:1594-1602. ®13. Lipsky P, van der Heijde D, St Clair W, Furst D, Kalden J, Weisman M, Breedveld F, Emery P, Keystone E, Harriman G, Maini R. The ATTRACT Investigators: 102-week clinical and radiologic results from the ATTRACT trial: a 2-year, randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial of infliximab (Remicade) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43 (Suppl):1216 14. Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Wasko MC, Moreland LW, Weaver AL, Markenson J, Finck BK: A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000, 343:1586-1593. 15. Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, Wasko MC, Moreland LW, Weaver AL, Markenson J, Cannon GW, Spencer-Green G, Finck BK: Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46:1443-1450. 16. Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, Katz LM, Lightfoot R Jr, Paulus H, Strand V: American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995, 38:727735. 17. Shergy W, Harshbarger JL, Lee W, McCain J, Schmizzi GF, Snow DH, Puett DW, Makarowski WS: Commercial experience with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients switching from etanercept to infliximab. Presented at the 3rd Annual European Congress of Rheumatology (EULAR) 2002 in Stockholm, Sweden, on 12–15 June 2002. 18. Aletaha D, Smolen JS: The rheumatoid arthritis patient in the clinic: comparing more than 1300 consecutive DMARD courses. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002, 41:1367-1374. 19. Berard A, Solomon DH, Avorn J: Patterns of drug use in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2000, 27:1648-1655. 20. Wong JB, Ramey DR, Singh G: Long-term morbidity, mortality, and economics of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001, 44:2746-2749. 21. Hawley DJ, Wolfe F: Are the results of controlled clinical trials and observational studies of second line therapy in rheumatoid arthritis valid and generalizable as measures of rheumatoid arthritis outcome: analysis of 122 studies. J Rheumatol 1991, 18:1008-1014. 22. Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Davis D, Macfarlane JD, Antoni C, Leeb B, Elliott MJ, Woody JN, Schaible TF, Feldmann M: Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor aa monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1998, 41:1552-1563. 23. Maini RN, Feldmann M: How does infliximab work in rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res 2002, 4 (Suppl 2):S22-S28. 24. Geborek P, Crnkic M, Petersson IF, Saxne T: Etanercept, infliximab, and leflunomide in established rheumatoid arthritis: clinical experience using a structured follow up programme in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2002, 61:793-798. 25. Power DJ, Villanueva I, Yocum DE, Nordensson KA: Comparison of survival curves between infliximab and etanercept: medication discontinuation as event [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46:S171. Correspondence David Yocum MD, Professor of Medicine, Director, Arizona Arthritis Center, University of Arizona, Health Sciences Center, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA. Tel: +1 520 626 6399; fax: +1 520 626 5018; e-mail: yocum@u.arizona.edu