Potatoes Royal Soc - Science behind your Garden

advertisement

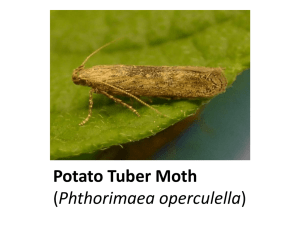

Potatoes Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum subspecies tuberosum) belong to the Solanaceae family that includes other important vegetables, such as tomatoes, eggplants and capsicum peppers, as well as some common weeds including nightshade and tobacco. Potatoes are annual plants that grow during the warmer months. The green tops die off or are killed by frosts as winter approaches. The potato tubers are actually swollen stems that grow under ground. If the tubers remain in the ground or are replanted after harvest they will send up shoots during the following spring and develop a new crop. The history of potatoes Potatoes originated in the South American countries of Peru and Bolivia. They were a staple crop in the high Andes, the mountain chain running the length of the continent, where they have been grown for several thousand years. The earliest record of potatoes in Europe comes from Spain and is dated 1573. The spread of the potato through Europe as a food item, rather than as a botanical curiosity, was a gradual process but by the 17th century it had become an important food crop especially among the poor. In Ireland during the 1800s many of the rural poor were living almost exclusively on potatoes with a little milk if they were lucky. This was possible because the potato is the best all round bundle of nutrition known to man. The earliest report of potatoes being grown in New Zealand comes from the French explorer de Surville in 1769. Captain Cook planted a garden in the Marlborough Sounds on his second visit in 1773. The Maori people were quick to see the advantages of the potato over their traditional root crop, kumara, particularly the ability of potatoes to grow in cooler climates, higher yields and easier storage. Potatoes soon became an important agricultural crop in New Zealand, both for domestic markets and export. The potato varieties grown in the 19th century were usually deep-eyed and much rougher shaped than those seen in the market today. A combination of plant breeding, better agronomic practises and less virus has seen major increases in yield and quality. In the 1920s yields averaged about 13 tonnes/ha but have risen to over 30 tonnes/ha today. Fifty years ago virtually all potatoes were marketed fresh and prepared and eaten in the home. Today over half the New Zealand potato crop is processed. French fries and crisps are the main products but a number of other lines are produced. However, such is the popularity of the potato that it remains the top selling vegetable in New Zealand. Interesting fact The potato is the fourth most widely grown food plant in the world after wheat, corn and rice. Worldwide 300 million tonnes are produced each year. A field of potatoes produces more calories and protein, more quickly, than any other crop. Planting and harvesting Potatoes are one of the few vegetable plants that are grown from a vegetative propagule, the seed tuber, as opposed to a true seed. This has important repercussions for the health of subsequent plants, because diseases, particularly viruses, can build up in the growing plant, including the tubers. When a tuber is replanted the following season the diseases accompany it and are transferred to the new plant. During the 1920s potato growers and the New Zealand Department of Agriculture realised the significance of planting diseased potato tubers, so a seed certification scheme was set up to provide growers with clean/healthy seed tubers. Designated seed tuber crops were grown in areas where aphids (the main vector for the spread of potato viruses) were less prevalent, such as the Canterbury foothills. Also any diseased plants were regularly removed during the growing season, and the crops were checked by inspectors who certified the health of the crop. Today most seed tubers are initially derived from tissue cultured plantlets that are completely clear of all diseases. Seed tubers are grown in the field under high levels of control until finally they are sold as table potatoes. Under this scheme growers do not save seed tubers from their own crops as they are constantly starting with new healthy stock. Home gardeners can also enjoy the benefits of high-health seed tubers by buying certified seed tubers rather than risking planting untested stock from an unknown source. Since potatoes produce their crop under the soil, it is important that soil conditions are suitable. A silt loam is the ideal soil for potatoes. Heavy clay soils tend to restrict the development of tubers while sandy soils fail to hold moisture critical for this fast growing plant. Both clay and sandy soil types can be improved by adding compost and manures. Potatoes prefer a slightly acid soil (pH 5–6) so avoid applying lime to areas where potatoes are to be grown. The potato crop requires large quantities of nitrogen and potassium (around 20 g/m2 each for a top crop) and lesser amounts of phosphate. Farmers usually obtain a soil test to help decide how much and what fertiliser to apply but this may not be practical for a home garden. Care should be taken with nitrogen as high rates can result in excessive foliage, late tuberization and watery tubers. If little fertiliser has been added in recent years up to 50 g/m2 of a balanced fertiliser could be worked into the soil prior to planting. Be careful not to apply fertiliser near the planted tuber as burning of the tender emerging shoots can occur. In fertile soils a light dressing of 10 g/m2 should be enough. Four to six weeks after planting a side dressing of 5 g/m2 of nitrogen could be useful if the crop is not as green and vigorous as expected or you suspect heavy rains may have washed some of the nitrogen out of the soil. Potatoes are frost tender, although they will tolerate light frosts and frost-damaged plants may come away again from beneath the soil. Thus, unless the potato tops can be covered, the seed tubers should be planted to emerge after most frosts have finished, which is from the end of October in southern areas of New Zealand. Potatoes can be planted at any time of the year in northern New Zealand. The potato tops usually take a couple of weeks to emerge from the ground. A technique known as pre-sprouting or chitting can be used to hasten crop development. The seed tubers are spread out in a warm, dry place under indirect light to encourage sprouts to form. The tubers should be planted when short, green sprouts appear and only those tubers with strong sprouts should be selected. If the seed tubers are kept in the dark the sprouts will etiolate (grow long and white) and are susceptible to damage during planting. Potatoes are planted either as an early crop, where tubers are harvested when small and eaten immediately, or as a main crop, where tubers are left to grow bigger and develop a thick skin which enables them to be stored for up to 6 months, depending on the variety. The seed tubers should be planted about 50 mm (early crops) to 100 mm (main crops) deep, with 250 mm (early crops) to 350 mm (main crops) between plants within a row. Rows should be 500–600 mm apart. When the plants are 200– 250 mm high they should be moulded up by drawing soil from within the row. Moulding up fulfils four objectives – it helps support the growing plant, kills weeds, prevents developing tubers becoming green, and protects tubers from tuber moth and blight spores. Once the plants are well established regular water is essential for good yield and quality. Uneven watering causes stress both to the tops, which create the nutrition for the developing tubers, and the tubers themselves, which can suffer physiological problems such as second growth and internal disorders. Harvest time depends on how impatient you are! After about 60 days from emergence small tubers will usually be present and they will increase in size until the tops die off. So it is a trade off between a low yield of very tasty immature potatoes and a bigger yield of mature ones. After the potato tubers have been dug up from the ground, they should be left to dry in the air for at least an hour, since moisture can encourage disease to develop during storage. When digging potatoes some damage is inevitable. Separate out any damaged potato tubers before storage and use these immediately, as the damaged tubers can easily become infected by diseases, which can then be transmitted to undamaged tubers. The tuber is capable of healing minor skin damage like scuffing, and keeping the tubers in warm, dark conditions for the first 2 weeks can help this process. After this time, store the tubers in a cool (ideally 5°C), dark, dry, rodent-free place. Avoid storing potatoes in warm temperatures, as this will encourage sprouting. Tubers are vulnerable to bacterial soft rot if they are exposed to moisture after tops have died. Ground storage (leaving the tubers in the soil until they are required) is possible, but not in soils that may become waterlogged. Popular potato cultivars in New Zealand Over the years hundreds of potato varieties have been grown in New Zealand. Some old favourites like Red Dakota, Aucklander Short Top, Epicure and Arran Baner have now been superseded but there are many others to choose from. Currently certified seed of over 50 potato cultivars is available to commercial growers. Some of these are grown especially for processing and others are new varieties being tested. The selection listed below are generally available to home gardeners. Early maturing cultivars that are usually best dug immature and eaten immediately Cliffs Kidney: requires fertiliser and water to get the numerous kidney-shaped tubers to a good size. Jersey Benne: as for Cliffs Kidney Liseta: vigorous variety with large, yellow-fleshed tubers. Swift: produces very little top growth but has very early yields of oval, cream-fleshed tubers. Mid-season cultivars that can be dug immature or left till mature Ilam Hardy: probably the easiest variety to grow but better suited to earlier harvest as it can become misshapen if left for maximum yield. Driver: good eating quality Maris Anchor: best as either an early crop or left to fully mature and has a reputation for good eating. Desiree: a popular general-purpose red-skinned variety. Karaka: a vigorous grower that is prone to tuber cracking under some conditions but has exceptional flavour as a boiled potato. Nadine: needs good growing conditions to yield well; although its lack of taste may not appeal to all, it is attractive and boils well. Main crop cultivars that are best left to fully mature – suitable for storing Rua: a very late maturing cultivar; probably the best available for long term storage. Moonlight: a recent release that is rapidly increasing in popularity due to heavy yielding ability and good flavour. Red Rascal: a high yielding red-skinned cultivar with good eating quality and medium–long storage. Agria: the most popular yellow-fleshed cultivar with a reputation for good flavour. Nutritional Value New Zealanders consume about 60 kg of potatoes per person every year. While potatoes are a primary source of carbohydrate they also contain significant amounts of other minerals and vitamins. For example, a medium sized potato (approximately 150 g) contains about 45% of a person’s daily requirement for vitamin C, 21% for potassium, 12% of dietary fibre and 10% of vitamin B6. Many of these minor elements are in a readily digestible form, which makes their contribution to the diet even more important. Coloured potatoes also contain antioxidant compounds, such as carotenoids and anthocyanins, which may provide health benefits. While the protein content of potatoes is only around 5%, the ‘biological value’ of that protein is 73, which is second only to eggs at 96, and way ahead of maize at 54 and wheat at 53. The biological value is an index of the amount of nitrogen absorbed from a food and retained by the body for growth and maintenance. Potatoes contain no fat but often this is added during the cooking and serving process. A wide range of methods can be used to cook potatoes, including boiling, baking, roasting, microwaving, steaming and frying. If potato tubers are exposed to light they will turn green due to the formation of the pigment chlorophyll. This colouration is also associated with the build-up of a bitter, toxic substance called solanine. Although poisonous, solanine is found no deeper than about 3 mm and is easily removed during peeling. Most modern potato cultivars have very low levels of solanine. Pests and Diseases Like any plant the potato is subject to various pests and diseases, although in New Zealand there are few pests of consequence. Diseases that destroy leaves affect tuber growth by reducing the ability of plants to photosynthesise, while those diseases that damage the stem disrupt the transport of nutrients from the leaf to the tuber. Other diseases infect the tuber causing rots. Integrated Garden Management for potatoes While chemical formulations are available for control of most pests and diseases they are often not the most practical solution in a small garden. In addition, many home gardeners prefer to use non-chemical methods of control. Successful control requires an understanding of the life cycle, environmental requirements and the level of damage caused by the pest or disease. Prevention is usually the first line of defence against pests and diseases, followed by early observation and identification. Integrated Garden Management (IGM) techniques can then be selected and applied in a multi-pronged approach towards control. These are described below and include crop rotation, choosing resistant cultivars, altering planting and harvesting dates, sowing clean seed tubers, controlling weeds, managing crops properly, applying sufficient fertiliser and water, utilising biological control agents and applying chemicals. Crop rotation It has long been known that repeated cropping in the same site can lead to a build-up of disease in the soil. Potatoes are no exception and while not often easy in a small garden you should try and avoid replanting the crop in the same part of the garden. Diseases such as Rhizoc, some tuber-rotting fungi, nematodes and powdery scab may survive in the soil or on tubers remaining from the previous crop. Digging all tubers at harvest time is sometimes difficult but tubers left in the ground do offer diseases a host on which to overwinter and a source of infection for subsequent crops. Similarly, putting rotten or infected tubers into the compost heap is unwise as diseases may survive and be spread back into the garden with the compost. Resistant cultivars Unfortunately no cultivars are resistant to every pest and disease. However, by identifying the most problematic disease in your area it may be possible to plant an appropriate cultivar. For example, if your garden suffers from powdery scab then planting Red Rascal, Moonlight, Swift or Nadine should reduce the problem. If late blight is prevalent in your region then Red Rascal, Moonlight, Rua, White Delight or Agria may help. Planting and harvesting date In some cases it may be possible to reduce the incidence or severity of a pathogen by altering the planting later or harvesting earlier. Planting later after soil temperatures have risen will help prevent Rhizoc and powdery scab damage, while earlier harvest may avoid tuber moth damage. Clean seed tubers Seed tubers are potential vehicles for disease transmission. Virtually all fungi, nematodes and viruses can be carried into the following crop on seed tubers. The pests and diseases or their symptoms are not always visible, and in the case of viruses are never apparent. While certified seed may not be completely disease-free, it has been grown to specified standards and offers the best chance of at least starting off with healthy plants. Weed control Controlling weeds helps remove reservoirs of disease. For example, potato leaf roll virus can be found in nightshade and Verticillium wilt in Shepherd’s purse and dandelion. Crop management and hygiene A good mould will help reduce infection from blight and the ability of tuber moth to infest tubers. Keeping the crop watered not only helps yield but prevents the soil cracking open, which can expose tubers to tuber moth and cause them to green. Burying crop debris will help prevent carryover onto subsequent crops. Fertilisers and manures There is some evidence that vigorously growing crops are less susceptible to infection. Alternaria blight will often attack weaker plants first. Good growing conditions and adequate fertiliser will help. However, excessive nitrogen fertiliser or nitrogen that is applied late in the season can lead to late maturity and susceptibility to bacterial soft rot. High soil pH (above 6.0) is conducive to common scab. Animals feed on potatoes infested with powdery scab will produce manure containing scab spores that can then infest subsequent crops. Care should be taken at planting with the placement of manures or fertilisers; developing sprouts can be burnt so place fertiliser below and to the side of seed tubers. Chemicals If all else fails it may be necessary to use chemical sprays or dusts. Always read the directions carefully and follow them. Increasing the rate of chemical is not a substitute for correct application. If repeated applications are required, try and use a chemical from a different chemical group to avoid the build-up of resistance within the pest or disease population. Pests, diseases and disorders of potatoes The main diseases causing crop loss in New Zealand and their control are outlined below. Several serious diseases that are not present in New Zealand are also briefly described to allow gardeners to be aware of them and understand the need to prevent them becoming established in this country. Fungal diseases Late blight (Phytophthora infestans). This disease is potentially the most devastating disease of potatoes. It suddenly appeared in Ireland in 1845 and 1846, and rapidly spread across the country, turning potato tops black within days and causing tubers to rot in the ground. The resulting famine resulted in an estimated one million lives lost and a further million emigrating to escape the abject poverty. The first symptoms of the disease on leaves are brown-black lesions that eventually spread across the entire leaf. On the underside of the leaf white ‘furry’ fungal growth can be seen. The disease can then spread to the tubers by spores being washed down the stems and into the soil. Mild, moist or humid conditions promote late blight. The blight spores do not survive long outside the host plant and persist from one season to the next on tubers either left in the ground or in storage. Early blight or Alternaria (Alternaria solani). The name early blight is problematic in New Zealand as the disease usually occurs late in the crop’s life, while late blight can occur at any time. The name Alternaria is probably less confusing. The first symptoms of this disease occur on the leaves in the form of small concentric rings of dead tissue which become angular where they are bordered by leaf veins. Alternaria can eventually completely defoliate the plant. Tubers are only infected where damage has occurred. The disease is favoured by hot, dry conditions with periods of humidity (e.g. after irrigation) to allow spores to spread. Stem canker or Rhizoc (Rhizoctonia solani). This fungus can affect the plant in two ways. Initially it attacks the sprouts as they push up to the soil surface girdling the stems and causing death of the stem. The other symptom of this fungus is seen as hard, black, dirt-like sclerotia that cannot be washed off the tubers. Apart from providing inoculum for stem canker in the following season this form of the disease is mainly a cosmetic problem. Verticillium wilt (Verticillium dahliae and V. albo-atrum). This disease is not common in home gardens unless the area has been continuously cropped with potatoes for several years. Specific symptoms are difficult to diagnose, as potatoes with the disease tend to look like they are dying down normally but this may occur earlier than usual. The disease can also be carried by some common garden weeds, such as shepherd’s purse and dandelions, so weed control is an important component of minimising disease risk. Providing good growing conditions (soil, fertiliser and water) for the potato plants and crop rotation should be practised to reduce sources of the disease. Bacterial diseases Black leg and bacterial soft rot (Erwinia carotovora). Black leg causes a black soft decay of the stem with resultant wilting and eventual death of the tops. Soft rot, as the name implies, results in a wet rot of tubers with a deligniated boundary between rotted and healthy tissue. Infected tubers form a source of inoculum for future generations. Black leg is favoured by cool, wet soils followed by high temperatures after plant emergence. Tubers are more susceptible to soft rot if exposed to free water and warm conditions. It is thus most prevalent in washed potatoes stored in plastic bags during the summer Scab. Common scab and powdery scab (actually a protozoan) both affect the tuber surface leaving it covered with corky, blister-like swellings. Common scab is prevalent in high pH soils that are dry at tuber formation. Powdery scab is more likely when soil conditions are cool and damp at tuberisation. Soilborne inoculum and infected tubers are the main source of infection. Nematodes Potato cyst nematode (Globodera spp.). This pathogen manifests itself by causing stunted yellow groups of plants in the field. Potato roots of infected plants contain tiny worm-like nematodes that are removing nutrients from the plant. Later they hatch into cysts, small spheres just visible to the naked eye, which remain attached to the surface of the roots. Each cyst contains 300-400 eggs capable of reinfecting a new potato crop. Viruses Virus diseases are seldom lethal initially but they debilitate the plant and reduce yield. If virus-infected seed tubers are planted, they transfer the virus into the resulting crop. The virus then multiplies further and causes severe losses in yield. The two most serious potato viruses in New Zealand are potato leaf roll virus and virus Y. Both these viruses are transmitted by aphids, primarily by green peach aphid, but many other aphids feed on the potato leaves and are capable of transmitting the viruses. Insects Potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella). This is a small grey-brown moth, about 10 mm long with a wingspan of about 12 mm. The white, oval eggs are laid on the underside of potato leaves and on exposed potato tubers. Larvae are grey or yellow-white with a dark brown head and reach a length of 15-20 mm. Larvae hatching on potato leaves form mines by tunnelling between the external leaf layers, and this action can completely destroy plants. Larvae hatching on tubers enter through the "eyes" and develop narrow tunnels into the tuber. Larval droppings can be seen at tunnel entrances. The potato tuber moth is found throughout New Zealand, particularly in areas with hot dry summers. Aphids. It is rare for aphids to cause direct damage to potato plants. Only when numbers are really excessive do they suck enough sap from the plant to cause serious damage. As explained above, the real threat is their potential to spread virus in seed crops. Physiological disorders A number of yield and/or quality lessening disorders can occur in potato tubers in the absence of pests and diseases. Some of the most common are listed below. Secondary growth, which results in irregular or knobby tubers, is caused by uneven growth. Cracks, which are medium to large splits or cracks in the tuber surface caused by watering after a dry spell. Hollow heart is a cavity in the centre of the tuber caused by rapid growth. Fleck or internal rust spots are small 1-2 mm brown flecks within the tuber flesh caused by the plant reabsorbing moisture from the tuber to support the tops. Blackspot is a blackened area just below the surface, but not visible until the potato is peeled. It is caused by an impact either from dropping the tuber or dropping something on it. Serious pests and diseases not yet present in New Zealand Wart. This disease results in the tuber surface becoming covered in corky, wart-like growths. The tuber is unusable. Isolated outbreaks of wart have been reported in the south of the South Island but fumigation has controlled them. Bacterial ring rot. A plant infected with this disease eventually wilt and the tubers suffer a light brown crumbly rot. Often a ring forms between the cortex and pith of the tuber. Colorado potato beetle. These yellow and black stripped adult insects and larvae are voracious feeders, which if left uncontrolled can decimate foliage. A final word The potato is not a humble vegetable as is often quoted. It is a fascinating crop to grow and rewards the grower with a high yielding, nutritious, versatile food. For those with a small garden try growing potatoes in car tires. Start with a couple of tires stacked up and filled with compost. Plant two or three seed tubers and as the plant grows add tires and cover the base of the plant with more compost and soil. Keep up the water and nutrients and see if you can approach the reported yield of over 15 kg of potatoes! Russell Genet 21 12 04