the colombian crisis in historical perspective

1

THE COLOMBIAN CRISIS IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Catherine C. LeGrand

Department of History

McGill University

April 2001

The purpose of this informal paper is to give those with relatively little background on Colombia some insight into the history of the country, the nature of the conflicts, and problems in understanding what is going on and finding solutions. The endnotes suggest further readings, both in English and Spanish. I thank Nancy Appelbaum for suggesting the structure of this essay and for co-authoring the first five pages.

2

Colombia today is in major crisis. Large areas of the countryside are controlled by guerrilla groups (there are 20,000 guerrillas in arms) and paramilitary forces (the paramilitaries claim 7,000 to 11,000 members). The government has no legitimate monopoly of force and is extremely weak; it does not and cannot effectively protect its citizens. Ninety-five percent of crimes never come to trial, judges receive death threats, and the army itself is accused of human rights violations. Since 1985 there have been 25,000 violent deaths per year, a total of 300,000 murders over the past decade and a half. Homicide is the leading cause of death for men between the ages of 18 and 45, and the second leading cause for women. In 2000, 1,800 people died in massacres and more than 3,500 were kidnapped for ransom.

Politicians, journalists, university professors, human rights workers, trade unionists, peasant leaders, and church activists are threatened, and disappearances and assassinations are daily occurrences.

1 Close to two million people, mostly the rural poor, have been displaced and are now refugees inside the country, while another 1.1 million Colombians, educated members of the upper and middle classes, have departed since 1996 for the

United States, Europe, and other Latin American countries (mainly

Ecuador and Costa Rica).

2 Meanwhile, since 1999, the economy has gone into deep recession, the worst Colombia has experienced since the 1930s.

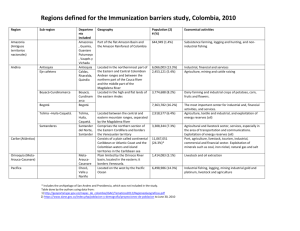

North Americans tend to associate violence in Colombia with the drug trade. Indeed, Colombia is the world's major supplier of cocaine and an increasingly important supplier of heroin. One year ago, Colombia suddenly leapt into the news in North America because the U.S. Congress, at President Bill Clinton's urging, voted to send $1.3 billion dollars mainly in military aid to

Colombia to fight the drug war. The Colombian government was already the largest recipient of U.S. military aid in the hemisphere and the third largest in the world, after Israel and

Egypt. About 80 percent of the additional $1.3 billion allotted to what is known as "Plan Colombia" will go to train three new

Colombian anti-drug army batallions and purchase military hardware, including fleets of brand new Blackhawk and Huey helicopters.

3

The stated aim of this controversial escalation in U.S. involvement in Colombia is to significantly reduce cocaine consumption in the United States (which is viewed as a problem of national security) by eradicating production of the coca plant in the southern jungles of Colombia. According to the United States, the Colombian government is fighting a life and death struggle against drug lords in cahoots with left-wing guerrillas.

4

In this paper I will argue that drugs are only part of a much more complicated story. United States policy does not take account of the complexity of the Colombian situation, the fact that the actors in the violence are not one or two forces, but several, and that parts of the military itself and certainly the paramilitaries have links to drug traffickers too. Many critics

3 of Plan Colombia fear that massive U.S. aid is a cover for United

States involvement in counterinsurgency warfare against Colombian guerrilla groups.

5 Moreover, it is part of a broader problem of militarizing what is a domestic health issue in the United

States.

The present violence in Colombia has deep historical roots.

6

My aim is to shed light on the historical background to the present crisis, drawing partly on my own research but much more on the work of Colombian historians and social scientists, especially those associated with the Jesuit Center for

Investigation and Popular Education (CINEP) and the Institute of

Political Studies and International Relations (IEPRI) at the

National University in Bogotá.

7

Let me begin with an overview of Colombian geography and demography, which is essential to understanding the layout and agrarian dimensions of the conflicts today. The size of

Arkansas, Texas and New Mexico combined, Colombia has a population of 42 million people. The western half of the country is broken by three dramatic ranges of the Andes mountains.

During the colonial period, the Spanish first settled in the cool, healthy mountains; there they founded Santafé de Bogotá, today Colombia's capital, and Medellín, presently its industrial center. Beyond the mountains lie the hot lowlands which include the Pacific coast (the Chocó region) and the Caribbean litoral where the Spanish colonial ports of Cartagena and Santa Marta still attract tourists. The tropical lowlands also include the southern Amazonian jungles, the vast Eastern Plains (the Llanos), and the valley of the Magdalena River (Colombia's Mississippi) which runs from deep in the interior between the eastern and central mountain ranges north to the bustling port of

Barranquilla on the Caribbean. The great majority of the population lives in the mountains and is Spanish-speaking, of mixed Spanish and native Indian descent. Along the Pacific and

Atlantic coasts, one finds significant black and mulatto populations and in the Magdalena valley, many people of mixed ancestry (Indian-black-Spanish). The eastern half of the country, the endless grassland plain that extends into Venezuela, always sparsely populated by cowboys and a few native hunting and gathering groups, has recently attracted international companies since the discovery of major oil deposits there in the past twenty years.

8 Finally, in the southern jungles, one finds scattered native Indian villages along the rivers that combine manioc agriculture with fishing and hunting. (Native people comprise only 3 percent of Colombia's population.

9 )

During the period of European colonial rule, from 1524 until

1819, some Spaniards consolidated large estates (haciendas) with tenant labor in the highlands around Bogotá and others ran cattle on the Caribbean coast. In the highlands one found some Indian communities (resguardos) and some small peasant holdings too, and, from the province of Antioquia, around Medellín, and the

Chocó, Spaniards exported gold from mines or panned the streams using slaves imported from Africa.

10

4

To grasp the agrarian dimensions of the current crisis, it is important to understand that the radius of Spanish economic activity in colonial times was relatively narrow; much land in the middle altitudes of the mountains and the lowlands remained

Crown or public lands (terrenos baldíos), forests or grasslands owned by no one and open to homesteading.

11 Thus, whereas the

United States and Canada both had western frontiers, Colombia possessed many scattered internal frontiers, including the

Magdalena River Valley, the Eastern Plains, and the southern jungles.

Like most other Latin American countries, after

Independence Colombia had trouble finding profitable export products. Finally, after 1870, Colombia began exporting coffee, and the coffee economy continued to expand in the twentieth century, shifting out of the eastern mountain range into the central cordillera to the south of Medellín.

12 Meanwhile, around

1900 the Boston-based United Fruit Company started up export banana plantations around Santa Marta, and the introduction of barbed wire and new pasture grasses precipitated a significant expansion of cattle ranching. The result of these novel economic activities (and the building of railroads, which also began in the 1870s) was that people began migrating out of the highlands into the middle altitudes and lowlands which became the epicenter of commercial production in the late nineteenth century.

Peasants left haciendas or small farm areas where the land had overfragmented to stake claims on public land down the mountain.

Such frontier settlers, known as colonos, cleared public land and put it into cultivation, but often a decade or so after they arrived, land sharks appeared on the scene, threatening to take over their fields with fabricated property titles. So the growth of agricultural exports stimulated colonization movements of poor people into previously unsettled areas, often followed by the privatization of the land by men with resources who succeeded in consolidating large private properties.

13 Often this enclosure process, by which homesteaders were expropriated, led to social conflict over public lands between peasant settlers and land entrepreneurs seeking to form profitable new haciendas in economically dynamic regions. This is the major form of rural conflict in Colombia historically and it is the major form today.

14

In sum, in colonial times, the Spanish tried to establish large estates and turn native Indians into tenant farmers, and they succeeded in doing so around Spanish cities. After

Independence one finds similar tendencies in wider areas of the country, regions that had remained public lands but in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries took on new value because lucrative commercial crops could be produced there.

With this historical geography in mind, let us turn now to the historical roots of the current violence in Colombia.

Colombian scholars emphasize that there is not just one but rather a multiplicity of violences afflicting the country today.

These include an enormous escalation in crime over the past two

5 decades, conflicts between youth gangs, and the so-called "social cleansing" groups that attack prostitutes, homosexuals, and drug addicts in cities. There are many forms of non-political as well as political violence.

15 In this paper I will focus specifically on political violence which is of direct interest for North

Americans who are concerned with human rights and possibilities for peace, who want to understand the implications of Plan

Colombia and who want to explore how international players might play a positive role in bringing the violence to an end.

The main domestic actors in the current political violence are: the civilian government, the guerrilla groups, the drug traffickers, the paramilitaries, the Colombian army, and civil society. The best way to make sense of what is going on is to examine these overlapping yet distinct forces one by one.

The Civilian Government

Colombia has not experienced military dictatorship like so many other Latin American countries. What is confounding about the current violence and the widespread violation of human rights is that it is occurring in what appears to be a political democracy.

Soon after Independence, in the 1830s and 1840s, two political parties took form in Colombia, the Liberals and the

Conservatives. Soon everyone came to identify themselves as

Liberal or Conservative: indeed loyalties to one or the other political party became primary, almost hereditary loyalties in the nineteenth century. It has often been said that in Colombia, one is born Liberal or Conservative; Gabriel García Márquez's novel In Evil Hour (La Mala Hora) vividly portrays how such affiliations were lived at the local level. Both the Liberals and the Conservatives were multiclass parties, led by elites and including middling groups and urban and rural poor. During the nineteenth century, numerous civil wars between the two parties errupted: indeed it is said that for 33 years of that century, civil wars were going on in one or another part of the country.

The seemingly interminable fighting culminated in the great War of a Thousand Days (1899-1902) which affected the whole country, killing, it is said, 100,000 people.

16

Of course, Liberal and Conservative parties also existed in most other Latin American countries in the nineteenth century.

What is unique about Colombia is the depth of party affiliation.

The parties were the first supra-local institutions with which people identified (most scholars of Colombia would say that the state took form later). And these parties have endured: Colombia is the only country in Latin America today where political parties that originated in the nineteenth century continue to dominate the political scene. In the 1930s and 1940s, Colombia did not give birth to an important populist party like APRA in

Peru, the Peronists of Argentina, or even the Mexican PRI. In

Colombia the emergence of the middle and working classes as political actors in the twentieth century was contained and constrained within the old two-party system.

17 Students of

6

Colombia question, then, what impact the extraordinary continuity of the two-party system has had on the formation of the Colombian state and its evident weakness. They question, too, whether or not emergent social sectors have been able to find real political expression for their concerns.

18

After peace treaties that ended the War of a Thousand Days in 1902, an exhausted Colombia experienced forty years of peace.

But violence broke out again in the late 1940s. The years 1946 to 1965 in Colombia are known simply as La Violencia. After the

U.S. Civil War and the Mexican Revolution, the Colombian

Violencia of the 1950s is the civil conflict in the Western

Hemisphere which killed the most people: it left 200,000 dead.

Some people say La Violencia began with the elections of

1946 in which the Liberals lost the presidency to the

Conservatives. But violence really errupted when the great

Colombian Liberal populist politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was murdered in the streets of Bogotá on April 9, 1948. Gaitan's death set off the largest urban riot in Latin American history, the Bogotazo, and it intensified tensions between Liberal and

Conservative party elites, which some say soon precipitated the breakdown of the state.

19 Political conflicts between party leaders set off a war in the countryside between peasant Liberals and Conservatives. During the late 1940s and early 1950s,

Conservatives controlled the government and military, and they also armed peasant groups which they turned into semi-military or irregular, what we call paramilitary, forces. In self-defense and retaliation, Liberals formed guerrilla groups to fight the

Conservatives and the government.

There are many interpretations of La Violencia of the 1950s.

Some see it as a renewal of the nineteenth century civil wars between Liberals and Conservatives, while others interpret it as a Conservative offensive against the followers of Jorge Eliécer

Gaitán. Still others say that the breakdown of the state released a multitude of local conflicts, some political and others socioeconomic. Still others see La Violencia as an abortive social revolution or, alternatively, as an offensive of landlords and business people against peasants and their allies who had begun to push for land redistribution.

20

Those who would make sense of continuities and changes in

Colombia should note that La Violencia of the 1950s was mainly a conflict between Liberals and Conservatives and those who died were mainly poor people in the countryside. In contrast, today the conflict between Liberals and Conservatives is no longer relevant. While these are still the main political parties in

Colombia, they are not the protagonists of the conflicts. Also, today's violence affects everyone -- both urban and country dwellers and the upper and middle classes as well as popular groups. Today the powerful -- presidential candidates, congressmen, and business people -- are targets of the violence, as are the rural poor. Furthermore (it is important to remember) in the 1950s, there was no drug trade in Colombia; at the time of the first Violencia, Colombia did not produce cocaine, marijuana

7 or heroin. These are new export crops. Thus the character of

Colombian violence has undergone major changes in recent times.

By 1958 the Liberal and Conservative elites became alarmed by the situation and fearful that social conflicts were getting out of control; so the leaders of the Liberal and Conservative parties came together to make peace through a political pact known as the National Front (Frente Nacional). The National

Front of 1958 was an agreement between the Conservative and

Liberal party directorates that they would alternate the presidency and divide political offices for the next fifteen years (1958-1974). So elections continued to be held, but everyone knew who would win: first a Liberal president, then a

Conservative, then a Liberal again. This was a kind of elitist, restricted democracy, in large measure a return to the "politics of gentlemen" who arranged the affairs of the nation over drinks at the Jockey Club.

21

The problem, then, was that there was no real change. The

National Front system was a formal democracy with two political parties and elections every few years, but as industrialization occurred and more people moved to cities, as society became more complex, and new social movements took form, they could not find independent political expression.

22

Beyond this need for the "democratization of democracy", those who have studied Colombia also emphasize that the Colombian state was very weak. Party affiliations, embodied in patronclient relations, took precedence; business and large landowning groups organized strong private gremios (lobbying groups) that played a major role in making economic policy; and the government did not have much of a presence in large areas of the country, especially in frontier zones of recent settlement. Also,

Colombia is very regionalized: there is not much sense of nation.

23

The Guerrillas:

In the early 1960s, out of the Liberal guerrilla movements of the first Violencia emerged a new kind of guerrilla -- armed left-wing movements that challenged the system. These new movements were inspired by the Cuban revolution and Fidel

Castro's success in using guerrilla tactics to take power (this is the period when young people all over Latin America sought to emulate Fidel and Che, and various small guerrilla groups, including the Sandinista Liberation Front in Nicaragua, took form). But in Colombia, the new guerrilla movements also had domestic roots, for the guerrillas that challenged the political monopoly of Liberals and Conservatives emerged directly out of the armed groups of the preceding decade.

During the 1970s and 1980s, several guerrilla organizations were active in Colombia.

24 I will focus here on the two main groups that remain active today: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN).

FARC is the oldest guerrilla army in Latin America and the largest and most important in Colombia. Founded in 1964, it

8 emerged out of the Colombian Communist Party and radical

Liberalism at the end of the first Violencia. Like other Latin

American Communist parties, the Colombian Communist party (PCC) was formed in the late 1920s, which happened to be a period of agrarian unrest in coffee regions in the eastern and central cordilleras. Although numerically small, the PCC involved itself almost immediately in these struggles over Indian communal lands, the rights of tenant farmers, and public land claims. This early rural orientation of the Communist party in Colombia and particularly its success in putting down roots in several areas of the countryside, some not far from Bogotá, is unusual in the

Latin American context.

25 During the Violencia of the 1950s, several parts of western Cundinamarca, southern Tolima, and Huila where the Communist party had generated support twenty years earlier came to be known as "independent peasant republics".

These Communist-influenced rural redoubts became refuge zones for peasants fleeing from partisan violence.

At the end of the first Violencia, in the early 1960s, the new National Front government attacked these peasant republics with aerial bombing, and people streamed out of them towards new frontier regions in the eastern plains and the northern part of the southern jungles. These refugees saw the state as the enemy because the government was attacking them. The new migrations became self-defense movements of armed colonization that went off in the by now familiar way to settle new areas of public lands and engage in subsistence agriculture. The FARC guerrilla movement originated in these colonization movements and settlement areas of the late violencia became FARC's local power bases.

26 FARC, then, was a real peasant movement, a response to official violence and military repression; in the 1960s and

1970s, FARC's strength lay in distant rural areas with virtually no state presence. It just so happened that these areas were apt for raising coca and, in the early 1980s with the international drug economy in full expansion, peasants in these areas began raising coca commercially.

27

In 1982, the Colombian government under Conservative

President Belisario Betancur began peace negotiations with the guerrillas. (It is important to note that peace negotiations have been going on for a long time in Colombia; indeed, they antedate the peace initiatives in El Salvador and Guatemala.

28 )

Many members of FARC agreed to put down their arms and create a legal political party. Thus in the mid-1980s out of FARC a new political party was born, known as the Patriotic Union (Unión

Patriótica -- UP). Over the next decade, members of the

Patriotic Union party who ran for political office, got involved in the union organizing, and so on, were assassinated by hired killers on motorcycles, called sicarios. More than 2,000 people associated with the Unión Patriótica political party were murdered in the late 1980s and early 1990s and the party was wiped out.

29 This experience -- and the murder of many of the more moderate, more politically oriented members of FARC who had joined the UP -- has influenced FARC's attitude toward peace

9 negotiations in the present.

In the early 1980s, when negotiations began, FARC had approximately 3,000 guerrillas in arms. In the past decade, especially the last five years, it has expanded exponentially in numbers and geographical reach.

30 Today FARC is especially strong in the southern jungle areas of Guaviare, Caquetá and

Putumayo (destinations of the armed colonization of the 1960s), but it has more than seventy fronts scattered all over the country, some very near Bogotá, with a total of 17,000 fighters in arms, one quarter of whom are women.

31 Whereas in the 1960s and 1970s, FARC was a self-defense movement that sought to be left alone in the outback, today it takes police stations, ambushes army patrols, and overruns army bases. It finances itself through kidnapping for ransom and taxing the production of coca, much of which is cultivated in regions under FARC influence. Traditionally guerrilla groups in Latin America kidnapped asking for the release of political prisoners and publicity for their political programs. In recent years, FARC has practiced on a large scale the kidnapping of men, women and children in cities and rural areas for immense sums of money.

While FARC says that it only targets the rich, many middle class people feel "kidnappable". This is true especially since FARC recently began the practice of "miraculous fishing" (la pesca milagrosa), which involves setting up roadblocks on highways and kidnapping people out of cars or buses after verifying their credit ratings by radio or laptop computer.

32

In the summer of 2000, FARC entered into peace negotiations once again, this time with the government of President Andrés

Pastrana who was elected on a peace ticket in 1999. These negotiations have not, however, made much progress and many doubt that FARC is serious about making peace. Meanwhile, because the negotiations are being carried out without a cease-fire, all sides are using force to strengthen their positions at the negotiating table.

The other guerrilla group active in Colombia today is the

National Liberation Army (Ejército Nacional de Liberación or

ELN). The ELN was formed in Santander in the early 1960s, around the same time as FARC, by Colombian university students who had gone to Cuba. ELN strongholds are the northwest of the country and the valley of the Magdalena River between Santander and

Boyacá on the east bank and Antioquia on the west. Like FARC, the ELN is strong in recent colonization areas where there are ongoing conflicts over land, and it is also strong in regions of historic and recent oil exploitation. The ELN is the guerrilla movement that Camilo Torres, the first Latin American priest to take up arms, joined, and until his recent death of natural causes, the organization's leader was a defrocked Spanish priest.

So beyond its Cuban inspiration, the ELN also finds its roots in the Liberation Theology movement in the Latin American Catholic

Church.

33 The ELN is significantly smaller (and weaker) than

FARC, with perhaps 5,000 adherents. In recent years, it has

10 engaged in spectacular mass kidnappings, and attacks on oil pipelines and electrical pylons, which many regard as a sabotage of the national economy. The ELN and the Colombian government are on the verge of entering into peace negotiations, with some

German church people attempting to play a mediatory role.

FARC and the ELN have rarely directly confronted each other, but they do not collaborate either in any concerted way, and in some zones they are in competition for popular support. The government's peace processes with each guerrilla group are entirely separate.

A few general comments about the guerrillas are in order.

First, they are particularly strong in colonization zones where there has never been a positive state presence. In these regions, they take on the role of local government. It is estimated that at present guerrilla groups have strong influence in at least one third of Colombian rural counties (municipios), which means they have a major say there in who is elected and how municipal funds are spent. In such zones, the guerrillas are responsible for road-building, education, and the provision of health services, and they tax most productive activities, including the highly profitable coca crop. Thus, the guerrillas have strong territorial control in many parts of the country, and some guerrilla territories have been legalized over the last three years by the Pastrana government's decision to demilitarize a large FARC-dominated area around San Vicente de Caguán as a precondition for peace negotiations to begin. This was, needless to say, a very controversial decision.

This situation leads to the crucial question of how is the

Colombian government to reestablish control and/or legitimacy in such regions? If and when peace negotiations come to fruition, is there a possibility that the guerrillas may remain the local government there, reestablishing connections with the national government?

34

During the past fifteen years, struggles over local political power have intensified in Colombia in part because of institutional reforms. Before 1988 departmental governors and local mayors were appointed by the central government. In an effort to democratize the political regime by decentralizing it so as to encourage greater participation, the Colombian government reformed the system to allow the popular election of mayors and governors.

35 This has had the unexpected effect of intensifying struggles over local control which have often turned violent, pitting local Liberal or Conservative political bosses

(traditional gamonales) against candidates from new groups including in the 1980s, the Union Patriótica party, and in the

1990s, the guerrillas and the paramilitaries.

36

Two further issues to be considered are the impact of the development of coca production on the guerrilla organizations since the 1980s and the relation of the guerrillas to social movements. Has drug money corrupted the guerrillas, and will a rich guerrilla seriously negotiate? According to Colombian

Prosecutor General Alfonso Gómez Méndez, just as drug money has

11 corrupted society and the establishment, it has also corrupted the anti-establishment.

37 Kidnapping and extortion have weakened the ethical bases of guerrilla action and undermined its social legitimacy. In Colombia it is generally believed that neither

FARC nor the ELN any longer has much of an ideological vision and that they are not doing much political organizing; rather they

(and particularly FARC) are engaged in war as business.

38

Why, then, the expansion of the guerrillas in numbers and military strength? Do the guerrillas represent "the people"?

Most would say no, but that rather the guerrillas and the paramilitaries are struggling over control over territory as a way to control people. Where there are guerrillas, where there is violence, there social movements are wiped out.

39

The Drug Traffickers and the Paramilitaries

Twentieth century Colombia has been mostly known for coffee and, among literary aficionados, for bananas (because of Gabriel

García Márquez's Nobel-prize winning novel One Hundred Years of

Solitude). But in the last forty years, Colombia experienced the sudden emergence of entirely new export products -- drugs.

40

First came marijuana in the 1960s and early 70s: pot-heads in

North America created a big demand, the U.S. sprayed the Mexican crop with chemicals, and Colombian suppliers moved into the void.

Marijuana growing and trafficking concentrated on the Caribbean coast in La Guajira, a traditional contraband area, and

Magdalena, in the Santa Marta banana zone from which the United

Fruit Company had just withdrawn. Marijuana in Colombia was a boom-bust industry: immensely profitable in the 1970s, Colombia's advantage soon evaporated as North American producers began to supply their own markets.

Then came cocaine in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Cocaine, then crack, emerged as the new drug-consumption fad in the United States.

41 Cocaine processors and overseas marketers from the big cities of Medellín and Cali eagerly stepped up to supply the demand; they began by processing coca produced in Peru and Bolivia by native Indian peasants. (Initially, only native people knew how to raise the coca plant, a pre-Columbian Andean crop used to treat colic, altitude sickness, hangovers, and hunger.) Before the 1980s, Colombians did not grow coca on a large scale, and they did not consume cocaine. The Colombian

"drug lords" who emerged in the 1980s were mainly people of lower middle class origin, entrepreneurs who responded to international demand, seeking social and economic mobility within Colombian society.

42

In the 1980s as Peruvians and Bolivians began processing their own coca and the United States implemented eradication campaigns, Colombians began producing the coca plant commercially. In the 1980s, thousands of families migrated out of the settled mountainous center of Colombia into the southern regions (the northern Amazonian jungle) where they cleared the forest and began producing coca on small farms. Traffickers went with them to buy the coca, process it, and arrange transport to

12 foreign markets. And the FARC guerrilla movement was already there in the new producing zones, or it soon expanded into the regions of new settlement. FARC was the local government; FARC taxed the growers, the traffickers, the truckdrivers, the shopkeepers. Raising coca was a prosperous way of life for all concerned: it is estimated that FARC today makes about half of its income or between $200 and $500 million U.S. dollars per year by taxing coca production and cocaine processing.

In Colombia drug trafficking relates to land in yet another way. The big drug lords in Medellín and Cali, smart entrepreneurs from humble backgrounds, were getting rich. They wanted to bring the drug money they made outside the country back to Colombia, and one of the major investments they made was in cattle ranching. From the early 1980s on, there is a clear pattern of cartel members investing drug profits in huge tracts of land for cattle ranching in the Magdalena River Valley, the

Eastern Plains, lowland Antioquia, and Córdoba. Economists who study the internal impact of the drug trade on Colombia emphasize that the drug lords did not invest in productive agriculture; indeed the economic resources of the drug producers have generally been used in non-productive and inefficient ways.

43

Because of the narco-investments, a significant trend toward the concentration of landholding is distingishable in cattle ranching regions since the early 1980s.

44

Meanwhile, in the same years, the guerrillas sought to get money by kidnapping the wealthy for ransom. And since the drug lords were becoming spectacularly rich, the guerrillas began kidnapping their relatives in Medellín and Cali. The drug lords and their families were, of course, terribly upset: in retaliation Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellín cartel, formed a paramilitary death squad to kill guerrillas called

"Muerte a los Sequestradores" (Death to the Kidnappers or MAS).

Also, the new drug-trafficking landlords formed private armies to protect their cattle ranches against guerrillas who might tax them and against peasants who might contest their land claims.

(These were former public land areas where social relations were conflictual.) So, beginning around 1982, many paramilitary groups took form that took the law into their own hands. They adopted some of the methods and organizational techniques of the guerrillas to retaliate against them. Such paramilitary groups were actually sanctioned by Colombian law from 1968 until 1989.

45

Where guerrillas were strong, the government stationed military batallions and intimate collaboration developed between large landowners (cattle ranchers and in some areas palm oil and banana producers), paramilitaries and specific military commanders who facilitated their activities. This collaboration, documented by Human Rights Watch, is so close that some international observers call the paramilitaries "irregular forces of the state". Many men who participate in paramilitary abuses are off-duty military or police.

46

During the 1990s, the paramilitaries have expanded greatly in size and have created a national organization called

13

Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) that claims 5,000 to 11,000 men in arms, a significant number of whom may be guerrilla defectors. AUC is led by Carlos Castaño, whose father was kidnapped and killed by FARC. The Castaños are drug traffickers themselves, operating through the Darien to Panama; Colombian judicial authorities have located paramilitary drug processing laboratories in the department of Antioquia.

47

The paramilitary groups emerged out of the cattle ranching areas of northern Colombia (the departments of Córdoba and

Bolívar), but in the last few years, like the guerrillas, they have significantly expanded their radius of action. The paramilitaries are highly organized, have urban as well as rural operatives, and now carry out operations all over the country.

Last year they actually boarded planes and flew into zones of guerrilla influence in eastern Colombia and south into Putumayo to massacre peasant villages there.

The paramilitaries (or "paras") call themselves anticommunist nationalists and demand political recognition. Carlos

Castaño gives interviews to the national media and demands representation at the peace negotiations.

48 Vehemently opposed to this, FARC says that peace negotiations cannot come to fruition until the government controls or disbands the paramilitaries.

On the ground, the paramilitaries engage in extortion and struggle with the guerrillas for territorial control. The form this takes is constant attacks on civilians whom the paras allege to be guerrilla sympathizers. In the 1980s the paramilitaries were responsible in part for the extermination of the Patriotic

Union party; in the 1990s they threaten and assassinate human rights workers, unionists, journalists, and professors, and they carry out the great majority of massacres in the countryside

(last year 405 massacres, more than one a day).

49 The paramilitaries are responsible for the displacement of thousands upon thousands of peasants as they carry out a dirty war against the civilian population in rural areas.

50 Without directly confronting the guerrillas, the paras seek to wrest control of territory from the guerrilla by expelling the civilian population and then to provide security for large estates, the vast cattle ranches that are consolidating there. The paras charge tribute for the protection they provide. So they are carrying out a reverse agrarian reform, expelling peasants to take over land.

The Military

What of the Colombian military? Historically the Colombian military has not played an autonomous political role.

51 The

Colombian armed forces did not take national political power in the 1960s and 1970s as did so many other Latin American militaries. Because it was functioning within a stable, elitist, formally democratic political order, the Colombian military remained subordinate to the civilian government. But the organization, mentality, values, and behavior of the Colombian military would be profoundly shaped by its very early involvement

14 in guerrilla warfare. This is an army predicated on counterinsurgency.

For fifty years the Colombian army has been continuously embroiled in fighting a war was within the country against guerrilla forces. In this situation of prolonged internal conflict, the military naturally became more and more influential in elaborating state decisions related to public order. Thus, over time, the Colombian military became a political actor although it did not take direct control of the national government. It is also important to realize that since World War

II, the United States has been the major foreign influence on the

Colombian military; the Colombian army was the only army in Latin

America to send troops to fight in the Korean War.

In the 1960s when the National Security doctrine, which focused on the threat of internal Communist subversion, was being elaborated (the national security doctrine that would profoundly affect all Latin American militaries), it made absolute sense to

Colombian officers. They were fighting Communist guerrillas inspired by the USSR and Cuba, they were being instructed in U.S. army schools, and in the 1970s they were reading training manuals produced by the militaries of Argentina, Chile and Brazil. From the 1960s on, as the Colombian government gave the military a carte blanche in fighting the anti-guerrilla war, the state and army became increasingly intertwined. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, some Colombian political scientists say, a partial military occupation of the civilian state had occurred.

Particularly during the presidency of Julio César Turbay Ayala

(1978-82), progressive unionists, intellectuals and students were labelled Communist sympathizers and roughed up, and both military and civilian officials expressed a polarized view of the world with great fear of "the internal enemy".

The government and the army agreed that, faced with a grave internal war, Colombia was experiencing exceptional times. So for decades Colombia lived under continuous and repeated declarations of state of siege. This does not mean that there were curfews; rather a legal state of siege legitimizes judgement of civilians by military tribunals when national security is threatened. In these years as well, the police were militarized, and the army became involved in state development projects (road-building, literacy programs, and health initiatives).

Furthermore, the civilian government declared certain conflictual areas militarized zones with military mayors. This occurred, for example, in the middle Magdalena River Valley around the oil town of Barrancabermeja. Often in these militarized zones particular commanders and troops forged very close relationships with landlords, drug traffickers, and paramilitaries.

52

Over time a kind of fragmentation occurred: we see a multiplication of guerrilla fronts, of army batallions in rural areas, and of paramilitary groups. What the guerrillas, soldiers and paramilitaries actually did and how they related to local populations varied, depending on local socioeconomic and

15 political circumstances.

The major problem, according to political scientist

Francisco Leal Buitrago, is that the civilian government never directly addressed the thorny question of what the relations between democratic governance and the armed forces should be under conditions of prolonged insurgency. The Colombian government never defined and enforced a role for the military that respects civilian legality, institutions, and human rights in a situation of ongoing internal warfare.

53

In the early 1980s a significant change began as the

National Security doctrine came under serious criticism throughout Latin America. Military governments in much of South

America gave way to civilian, democratic regimes. Colombia is part of this trend in its own specific way. In 1982 President

Belisario Betancur initiated peace negotiations: he expressed his desire to deal with the various guerrilla groups politically rather than militarily, that is, to incorporate them into democratic life as political parties. So President Betancur raised the state of siege, proclaimed amnesty for the guerrillas, and opened dialogue with them, and he did not allow the military to play a major role in the peace negotiations. Betancur also established a Presidential Commission for Human Rights; indeed, in the late 1970s and early 1980s some people in Colombia began to talk seriously about human rights.

54

As the peace process got underway, discussion also began about the need to trace the line between legitimate military actions and military excesses or what now began to be called military violations of human rights. The violation of human rights by the military and the paramilitaries it collaborated with stemmed from the military's embrace of the Doctrine of

National Security and the fanatic anti-Communism it implied. For this reason, military officials opposed the peace process and this new talk of human rights because it limited their normal capacity for operations. They saw it as an underhanded way for

"the subversives" to expand their influence and attack the nation.

Since the other participants at the Berkeley conference

"Colombia in Context" will concentrate on what happened in the

1980s and 1990s 55 , in closing I want only to mention a few crucial elements that should be kept in mind.

First, peace negotiations in Colombia have been going on -- with fits and starts -- for twenty years. In the late 1980s,

President Virgilio Barco came to an agreement with the M-19 guerrilla movement, which turned itself into a legal political party.

56 In 1990 President César Gaviria called a constituent assembly to write a new Constitution for the first time since

1886. The hope was that the Constitution of 1991 would bring peace by creating more decentralized, more participatory institutions, thus strengthening and legitimating the state by making it more inclusionary. Despite the best intentions, it did not work.

57 Ironically efforts at peace negotiations and at constitutional reform to provide the legal base for a more

16 pluralistic, democratic Colombia were taking place iin the same years that the leftist insurgency and the paramilitaries gathered strength and the Colombian state became more and more unable to cope.

Second, I want to emphasize that the regions where new commercial crops and export products have developed over the past forty years are the most violent places in Colombia today. These include areas of coca production in the southern jungles

(Guaviare, Putumayo) which are the bases of the FARC guerrilla movement and targets of paramilitary incursions and aerial spraying, the cattle ranching zones of the Magdalena River valley and the Atlantic coast, the oil areas of the Eastern Plains, and the new banana zone of Urabá near the Panamanian border. Most are recently colonized public land areas without a history of effective state presence. They are also areas of Indian, black, and mixed race people who seem to have experienced more death and displacement than other Colombians.

58

One final point: over the past few decades, we see the emergence of many interesting new social movements: a national peasant movement that later fell apart, a national aboriginal organization, various regional initiatives of Afro-Colombians, civic strikes (paros cívicos), coca unions, movements of urban settlers, of refugees, human rights organizations, peace movements.

59 So what is Colombian civil society? What role has it been playing, and what role can it play in bringing the conflicts to an end? Much of the Colombian writing indicates that civil society is very weak and fragmented and lacks influence in Colombia.

60 One major question is: has the violence of the last twenty years undermined social movements and made them impossible; or alternatively has it generated new movements, new kinds of concern and unity essential to bringing the violence to an end? What are the effects of the drug economy on popular mobilization? What are the effects of the economic recession?

And what effects will Plan Colombia have?

To conclude, in this essay I have tried to explore the current Colombian situation by not focusing solely on drugs and hardly at all on the United States, but rather by conveying some insight into the internal complexity of the situation and its historical roots.

What we have in Colombia is a weak government trying to deal with increasingly strong private forces who are using violent means to accumulate economic resources (money, land); to establish control over whole regions or territories; and to seek political advantage. The guerrillas are playing on antiimperialism and nationalism; the paramlitaries play on anticommunism and nationalism; the government is asking for foreign aid, says it wants to negotiate, yet at the same time is militarizing. The government has no workable judicial system, it does not control force in the country or even its own military, and it is losing control over many regions of the country. The worsening Colombian crisis is generating great nervousness in neighboring countries such as Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela and

17

Panama who express concern that the war and its human devastation may be expanding into the Amazon basin and into the Darien rainforests of Panama.

The nature of the violence has changed a great deal since the 1950s. Although some observers maintain that war in Colombia has been going on for fifty years, it is important to recognize that there was no drug trade in the 1950s, no left-wing guerrilla movements, and no paramilitaries as there are today.

61 Now the violence is affecting the whole society -- all regions of the country and all social classes, though some much more directly than others. And today's violence is combined with a serious economic recession and high unemployment, which fuels the recruiting of young people by the paramilitaries and the guerrillas. The responsibility of the Colombian state for the situation is not entirely clear. And there is no obvious solution: peace negotiations are not making much progress 62 and

President Andrés Pastrana's term in office is nearly over; the presidential elections of 2002 are sure to bring more uncertainty and probably more violence.

I regret to end on a pessimistic note, but this is a grave situation of tragic proportions, the end of which is not yet in sight. Colombians have asked for international help, but a simple reading of the Colombian situation that focuses on "the drug problem" at the expense of everything else does not create understanding or generate solutions. It is important to attend to the valiant efforts of Colombians of all walks of life to reconceptualize community, region, state, nation and development in ways that will overcome exclusion and bring peace and prosperity in a period when neo-liberalism and globalization limit the parameters of what is possible. At this point, it is essential that international observers who would act ethically and consciously in Colombia attend to the internal causes, domestic interpretations and debates 63 , and the evolving complexity of the conflicts; the Colombian crisis requires sensitivity to the fragmented, privatized, multi-dimensional realities of the struggle for resources, territory, and political power that informs contemporary violence in Colombia and makes it so immensely difficult to resolve.

18

NOTES

1.. For a vivid description of the current situation, see Gonzalo Sánchez G.,

"Introduction: Problems of Violence, Prospects for Peace," in Violence in Colombia,

1990-2000: Waging War and Negotiating Peace, ed. Charles Bergquist, Ricardo Peñaranda and Gonzalo Sánchez G. (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 2001), 1-38. Also

"Survey: Colombia, Drugs, War and Democracy," The Economist, April 21-27, 2001, 16 pp.

2.. "Prosperous Colombians Flee, Many to U.S., to Escape War," The New York Times,

April 10, 2001.

3.. Mary Roldan, "Plan Colombia: From Intent to Execution," Radical Historian's

Newsletter (forthcoming).

4.. Winnifred Tate, "Repeating Past Mistakes: Aiding Counterinsurgency in Colombia,"

NACLA Report on the Americas 34:2 (Sept./Oct. 2000), 16-19.

5.. See NACLA Report on the Americas [special issue on "Colombia: Old War, New

Guns"] 34:2 (Sept./Oct. 2000), 15.

6.. Useful overviews of Colombian history include David Bushnell, The Making of

Modern Colombia: A Nation in Spite of Itself (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1993); Malcolm Deas, "Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, c. 1880-1930," in The

Cambridge History of Latin America, vol. 5, ed. Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1985), 641-663; Christopher Abel and Marco Palacios, "Colombia,

1930-1958," and "Colombia Since 1958" in The Cambridge History of Latin America, vol., 8, ed. Leslie Bethell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 587-627,

629-686; Marco Palacios, Entre la legitimidad y la violencia: Colombia 1975-1994

(Bogotá: Editorial Norma, 1995); and Jenny Pearce, Colombia, Inside the Labyrinth

(London: Latin American Bureau, 1990).

7.. Major centers for study of the violence include IEPRI and CINEP in Santafé de

Bogotá and the Instituto de Estudios Regionales (INER) at the Universidad de

Antioquia in Medellín. Important journals for those who want to understand Colombian interpretations of the current situation include Análisis Político (IEPRI), Revista

Foro, Controversia [CINEP], and Estudios Políticos [Instituto de Estudios Políticos,

Universidad de Antioquia].

8.. Pearce, 98-102; Jane M. Rausch, A Tropical Plains Frontier: The Llanos of

Colombia, 1531-1831 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984) and The

Llanos Frontier in Colombian History, 1830-1930 (Albuquerque: University of New

Mexico Press, 1993).

9.. Mario Murillo, "Colombia: Confronting the Dilemmas of Political Participation,"

NACLA Report On the Americas ("Report on Indigenous Movements") 29:5 (March/April

1996), 21.

10.. See Ann Twinam, Miners, Merchants, and Farmers in Colonial Colombia (Austin:

University of Texas Press, 1982); and Eduardo Posada Carbó, The Colombian Caribbean:

A Regional History, 1870-1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

11.. Terrenos baldíos, also known as tierras baldías in Colombia, are equivalent to public land in the United States or Crown land in Canada.

12.. On the history of Colombian coffee, see Marco Palacios, Coffee in Colombia

(1850-1970): An Economic, Social, and Political History (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1980); and Charles Bergquist, "Colombia" in Labor in Latin America

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 274-375.

13.. The only area where the formation of large private properties did not occur was in central Colombia -- in Antioquia, Caldas, northern Tolima and northern Valle -- which became a coffee smallholding frontier, symbolized by Juan Váldez (the emblem of

19 the Colombian Federation of Coffee Growers). The classic study of the anomalous

"democratic" colonization process in Antioquia is James Parsons, Antioqueño

Colonization in Western Colombia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949).

14.. See Catherine LeGrand, Frontier Expansion and Peasant Protest in Colombia,

1850-1936 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985) and Catherine LeGrand,

"Colonization and Violence in Colombia: Perspectives and Debates," Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 14:28 (1989), 5-29.

15.. The first major analysis of the multiple forms of violence in Colombia was

Comisión de Estudios sobre la Violencia, Colombia: Violencia y Democracia (Informe presentado al Ministerio de Gobierno) (Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de

Colombia/COLCIENCIAS, 1988).

16.. Insightful analyses of the social bases of the Liberal and Conservative parties in nineteenth century Colombia are Frank Safford, "Social Aspects of Politics in

Nineteenth Century Spanish America: New Granada, 1825-1850," Journal of Social

History 5 (1972), 344-370; Richard Jon Stoller, "Liberalism and Conflict in Socorro,

Colombia, 1830-1870" (Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 1991); and James E. Sanders,

"Contentious Republicans: Popular Politics, Race, and Class in Nineteenth-Cuentury

Southwestern Colombia" (Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2000). On the civil wars, see Charles Bergquist, Coffee and Conflict in Colombia, 1886-1910 (Durham,

N.C.: Duke University Press, 1978), and Gonzalo Sánchez and Mario Aguilera, eds.,

Memoria de un país en guerra: Los Mil Días 1899-1902 (Bogotá: IEPRI, UNIJUS and

Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2001).

17.. See Herbert Braun, The Assassination of Gaitán: Public Life and Urban Violence in Colombia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985); and Daniel Pécaut, Orden y violencia: Colombia 1930-1954, 2 vols. (Bogotá: CEREC y Siglo XXI, 1987).

18.. See Marco Palacios, "Colombian Experience with Liberalism: On the Historical

Weakness of the State," in Colomobia: The Politics of Reforming the State, ed.

Eduardo Posada-Carbó (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1998), 21-44; Gary Hoskin, "The

State and Political Parties in Colombia," in Ibid., 45-70; and Alejandro Reyes, "La violencia y el problema agrario en Colombia," Análisis Político 2 (Sept.-Dec. 1987),

30-46.

19.. See Braun, Assassination of Gaitán; Pécaut, Orden y violencia; Paul Oquist,

Violence, Conflict and Politics in Colombia (New York: Academic Press, 1980); and

Gonzalo Sánchez G., ed., Grandes potencias, el 9 de abril y La Violencia (Bogotá:

Planeta Colombiana, 2000).

20.. On the historiography of the Violencia of the 1950s, see Gonzalo Sánchez G., "La

Violencia in Colombia: New Research, New Questions," Hispanic American Historical

Review 65:4 (Nov. 1985), 789-807; Mary Roldan, "Genesis and Evolution of La Violencia in Antioquia, Colombia (1900-1953)" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University 1992), chapt. 1

"Introduction to the Historiography of La Violencia"; Ricardo Peñaranda, "Conclusion:

Surveying the Literature on the Violence," Violence in Colombia: The Contemporary

Crisis in Historical Perspective, ed. Charles Bergquist, Ricardo Peñaranda and

Gonzalo Sánchez (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1992), 293-314; and Catherine

LeGrand, "La política y la violencia en Colombia (1946-1965): interpretaciones de la década de los ochenta," Memoria y Sociedad 2:4 (Nov. 1997), 79-104.

21.. The words are Herbert Braun's, from Assassination of Gaitán. On the National

Front agreement and its outcomes, see Jonathan Hartlyn, The Politics of Coalition

Rule in Colombia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988) and Albert Berry,

Ronald G. Hellman and Mauricio Solaun, eds., Politics of Compromise: Coalition

20

Government in Colombia (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1980).

22.. This was the dominant interpretation among Colombian intellectuals in the

1980s. See, for example, William Ramírez Tobón, "Violencia y democracia en

Colombia," Análisis Político 3 (Jan.-April 1988), 64-78, and Luís Alberto Restrepo,

"La guerra como sustitución de la política," in Ibid., 80-93.

23.. See Pécaut, Orden y violencia, Posada-Carbó, Politics of Reforming the State;

Jonathan Hartlyn "Producers Associations, the Political Regime and Policy Process in

Contemporary Colombia," Latin American Research Review 20:3 (1985): 111-138;

Francisco Leal Buitrago and A. Davila, Clientelismo: El sistema político y su expresión regional (Bogotá, 1990); and Fabio Zambrano Pantoja, Colombia: Pais de regiones (Bogotá: CINEP/Colciencias, 1998).

24.. See Eduardo Pizarro, "Revolutionary Guerrilla Groups in Colombia," in Violence in Colombia: The Contemporary Crisis in Historical Perspective, ed. Charles Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1992), 169-194; and "Appendix:

Colombia's Major Guerrilla Movements," in Cynthia J. Arnson, ed., Comparative Peace

Processes in Latin America (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 196-199.

25.. On the agrarian conflicts of the late 1920s and early 1930s and the involvement of the Colombian Communist Party, see Medófilo Medina, Historia del Partido Comunista de Colombia, vol. 1 (Bogotá: Centro de Estudios y Investigaciones Sociales, 1980);

Medófilo Medina, "La resistencia campesina en el sur de Tolima," in Pasado y presente de la Violencia en Colombia, ed. G. Sánchez and R. Peñaranda (Bogotá: Fondo Editorial

CEREC, 1986), 233-266; Gloria Gaitán, Colombia: la lucha por la tierra en la década del treinta: Genesis de la organización sindical campesina (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo,

1976); Gonzalo Sánchez, Las ligas campesinas en Colombia (Bogotá, 1977); Michael F.

Jimenez, "The Limits of Export Capitalism: Economic Structure, Class, and Politics in a Colombian Coffee Municipality, 1900-1930" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1985) and his forthcoming book, "Struggles on an Interior Shore: Wealth, Power and

Authority in the Colombian Andes" (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press); and Elsy

Marulanda, Colonización y conflicto: Las lecciones del Sumapaz (Bogotá: Tercer

Mundo/IEPRI, 1991).

26.. See Gonzalo Sánchez Gómez, "Rehabilitación y Violencia bajo el Frente

Nacional," Análisis Político 4 (May-August, 1988), 21-42; William Ramírez Tobón, "La guerrilla rural en Colombia: una via hacia la colonización armada?" Estudios Rurales

Latinoamericanos 4 (May-August 1981), 199-209; Alfredo Molano Bravo, "De la Violencia a la colonización: un testimonio colombiano," Estudios Rurales Latinoamericanos 4

(Sept.-Dec. 1981), 257-86; Arturo Alape, La paz, la violencia: Testigos de excepción

(Bogotá: Planeta Colombiana, 1985); Alfredo Molano, "Violence and Land Colonization," in Violence in Colombia, ed. C. Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly

Resources, 1992), 195-216; Alfredo Molano, Siguiendo el corte: Relatos de guerras y de tierras (Bogotá: El Ancora, 1989); and Eduardo Pizarro Leongómez, Las FARC (1949-

1966): de la autodefensa a la combinación de todas las formas de lucha (Bogotá:

Tercer Mundo and IEPRI, 1991). For the history of guerrilla movements in Colombia, see Eduardo Pizarro Leongómez, Insurgencia sin revolución: La guerrilla en Colombia en una perspectiva comparada (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo, 1996).

27.. See Alfredo Molano, Selva adentro: Una historia oral de la colonización del

Guaviare (Bogotá: El Ancora Editores, 1987); and Jaime Eduardo Jaramillo, Leonidas

Mora and Fernando Cubides, Colonización, coca y guerrilla (Bogotá: Universidad

21

Nacional de Colombia, 1986).

28.. For the history of the peace negotiations in Colombia, see Marc Chernick,

"Negotiating Peace amid Multiple Forms of Violence: The Protracted Search for a

Settlement to the Armed Conflicts in Colombia," in Cynthia J. Arnson, ed.,

Comparative Peace Processes in Latin America, ed. Cynthia J. Arnson (Washington,

D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999),

159-195; and Jesús Antonio Bejarano, "Reflections," in Ibid., 201-204. Carlo Nasi, in his Ph.D. dissertation in progress (Dept. of Political Science, Stanford University), compares the history of peace negotiations in Colombia to Guatemala.

29.. An excellent collection on the 1980s in Colombia is Francisco Leal Buitrago and

León Zamosc, eds., Al filo del caos: Crisis política en la Colombia de los años 80

(Bogotá: Tercer Mundo/IEPRI, 1991).

30.. For some explanations of this expansion, see Camilo Echandía, "Expansión territorial de las guerrillas colombianas: geografía, economía y violencia," in

Reconocer la guerra para construir la paz, ed. Malcolm Deas and María Victoria

Llorente (Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, CEREC and Editorial Norma, 1999), 99-150; and

Carina Peña, "La guerrilla resiste muchas miradas. El crecimiento de las FARC en los municipios cercanos a Bogotá: Caso del frente 22 en Cundinamarca," Análisis Político

32 (Sept. 1997), 81-100.

31.. See Alma Guillermoprieto, "Our New War in Colombia," The New York Review of

Books 48:6 (April 13, 2000), "Colombia: Violence without End?" in Ibid., 48:7 (April

27, 2000), and "The Childrens' War" in Ibid., 48:9 (May 11, 2000). This excellent analysis of the situation in Colombia, published in Spanish as Las guerras en

Colombia (Bogotá: Aguilar, 2000), provides much information on FARC and the paramilitaries. See also Patricia Lara S., Las mujeres en la guerra (Bogotá: Planeta

Colombiana, 2000).

32.. See Patrick Symmes, "Miraculous Fishing: Lost in the Swamps of Colombia's Drug

War," Harper's Magazine (December 2000), 61-71.

33.. On the ELN, see Jaime Arenas Reyes, La guerrilla por dentro: Análisis del ELN colombiano (Bogotá, 1971); Andrés Peñate, "El sendero estratégico del ELN: Del idealismo guevarista al clientelismo armado," in Reconocer la guerra para construir la paz, ed. M. V. Llorente and M. Deas (Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes, CEREC, and

Editorial Norma, 1999), 53-98; and Herbert Braun, Our Guerrillas, Our Sidewalks: A

Journey into the Violence of Colombia (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1994).

34.. See "Hay que hacer una reforma política," Interview with Marco Palacios,

Semana, April 9, 2001.

35.. See various articles in Eduardo Posada-Carbo, ed., Colombia: the Politics of

Reforming the State (London: Macmillan, 1998), especially Gustavo Bell Lemus, "The

Decentralized State: An Administrative or Political Challenge?", 97-107; and Pilar

Gaitán and Carlos Moreno Ospina, "Bibliografía temática: Decentralización, democracia local y autonomía municipal en Colombia," Análisis Político No. 4 (May-August 1988),

127-130.

36.. Mauricio Romero, "Changing Identities and Contested Settings: Regional Elites and the Paramilitaries in Colombia," International Journal of Politics, Culture, and

Society 14:1 (2000), 51-69; Leah Carroll, "Palm-makers, Patrons and Political

Violence in Colombia: A Window of Opportunity for the Left Despite Trade

Liberalization," Political Power and Social Theory 13 (1999), 149-200; and Leah

Carroll, "Violent Democratization: The Effect of Political Reform on Rural Social

Conflict in Colombia" (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 2000).

22

37.. Presentation by Dr. Alfonso Gómez Méndez, Fiscal General de la Nación, McGill

University, Montreal, Quebec, November 24, 2000.

38.. See Nazih Richani, "The Political Economy of Violence: The War-System in

Colombia," Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 39:2 (Summer 1997), 37-

81. Marc Chernick argues against this position in "Elusive Peace," NACLA Report on the

Americas 34:2 (Sept./Oct. 2000), 32-33; See also "Raul Reyes: Guerrilla Spokesperson,

Colombia," Interviewed by Mario Murillo and Victoria Maldonado NACLA Report on the

Americas 31:1 (July-Aug. 1997), 23-25.

39.. See Alejandro Reyes Posada and Ana María Bejarano, "Conflictos agrarios y luchas armadas en la Colombia contemporanea: Una visión geográfica," Análisis Político No. 5

(Sept.-Dec. 1988), 6-27.

40.. See Hermes Tovar, "La coca y las economías exportadoras en América Latina: El paradigma colombiano," Análisis Político No. 18 (Jan.-April, 1993), 5-31; and Darío

Betancourt and Martha L. García, Contrabandistas, marimberos y mafiosos; Historia social de la mafia colombiana (1965-1992) (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo, 1994).

41.. See Philippe Bourgois, In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in the Barrio

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

42.. Francisco Leal Buitrago, "Structural Crisis and the Current Situation in

Colombia," Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 14:28 (1989), 31-

49; and Mary Roldan, "Colombia: Cocaine and the 'Miracle' of Modernity in Medellín," in Cocaine: Global Histories, ed. Paul Gootenberg (New York: Routledge, 1999), 165-

182.

43.. See Mauricio Reina, "Drug Trafficking and the National Economy," in Violence in

Colombia, 1900-2000: Waging War and Negotiating Peace (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly

Resources, 2001), 83-84. Excellent studies of the internal impact of the drug trade in Colombia include Francisco Gutiérrez Sanín, "Politicians and Criminals: Two

Decades of Turbulence, 1978-1998," International Journal of Politics, Culture and

Society 14:1 (2000), 71-87, Alvaro Camacho Guizado and Andrés López Restrepo,

"Perspectives on Narcotics Trafficking in Colombia," in Ibid., 151-182, and Pierre

Salama, "The Economy of Narco-Dollars: From Production to Recycling of Earnings," in

Ibid., 183-203.

44.. See Reina; and León Zamosc, "Transformaciones agrarias y luchas campesinas en

Colombia: Un balance retrospectivo (1950-1990)," Análisis Político No. 15 (Jan.-Apr.

1992), 35-66.

45.. On the history of the paramilitaries and their tactics, see Carlos Medina

Gallego, Autodefensas, paramilitares y narcotráfico en Colombia: Origen, desarrollo y consolidación. El Caso Puerto Boyacá (Bogotá: Editorial Documentos Periodísticos,

1990); Carlos Medina Gallego and Mireya Tellez Ardila, La violencia parainstitutional, paramilitar y parapolicial en Colombia (Bogotá: Rodríguez Quito

Editores, 1994); Adolfo Atheortua, El poder y la sangre: Las historias de Trujillo,

Valle (Cali: CINEP/Pontífica Universidad Javeriana, 1995); Richani, "Political

Economy of Violence"; Nazih Richani, "The Paramilitary Connection," NACLA Report on the Americas 34:2 (Sept./.Oct 2000), 38-42; Fernando Cubides C., "From Private to

Public Violence: The Paramilitaries," in Violence in Colombia 1990-2000, ed. C.

Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, 2001), 127-149; and Romero, "Changing Identities and

Contested Settings". In her forthcoming book Hegemony and Violence: Class, Culture adn Politics in Twentieth Century Antioquia, Mary Roldan explores the origins of paramilitary groups during La Violencia of the 1950s.

46.. See Human Rights Watch/Americas-Arms Project, Colombia's Killer Networks: The

23

Military-Paramilitary Partnership and the United States (N.Y.: Human Rights Watch,

1996); and Human Rights Watch, "The Ties that Bind: Colombia and Military-

Paramilitary Links," vol. 12 no 1 (B), Feb. 2000.

47.. Presentation by Dr. Alfonso Gómez Méndez, Fiscal General de la Nación, McGill

University, Montreal, Quebec, November 24, 2000.

48.. Germán Castro Caycedo, "Los paramilitares," En secreto (Bogotá: Planeta

Colombiana, 1996), 139-233; and Robin Kirk, "A Meeting with Paramilitary Leader

Carlos Castaño," NACLA Report on the Americas ["The Wars and Counterinsurgency in

Chiapas and Colombia"] 31:5 (March/April 1998), 3-31.

49.. A massacre involves the killing of five or more people at the same time.

50.. On displacement in Colombia, see Richani, "Political Economy"; Maria Carrion,

"Barrio Nelson Mandela," in NACLA Report on the Americas 34:2 (Sept./Oct. 2000), 43-

47; Donny Meertens, "Victims and Survivors of War in Colombia: Three Views of Gender

Relations," Violence in Colombia 1990-2000, ed. C. Bergquist et al. (Wilmington,

Del., 2001), 151-170; Donny Meertens, "Facing Destruction, Rebuilding Life: Gender and the Internally Displaced in Colombia," Latin American Perspectives, Issue 116,

28:1 (Jan. 2001), 132-148; Daniel Pécaut, "The Loss of Rights, the Meaning of

Experience and Social Connection: A Consideration of the Internally Displaced in

Colombia," International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 14:1 (2000), 69-

105; and Nora Segura Escobar, "Colombia: A New Century, an Old War, and More Internal

Displacement," in Ibid., 107-127.

51.. Much of the following section on the Colombian military is based on Francisco

Leal Buitrago, "Surgimiento, auge y crisis de la doctrina de seguridad nacional en

América Latina y Colombia," Análisis Político, 15 (Jan.-April 1992), 6-34. See also

Francisco Leal Buitrago, El oficio de la guerra: La seguridad nacional en Colombia

(Bogotá: IEPRI/Tercer Mundo, 1994); Andrés Dávila Ladrón, El juego del poder:

Historia, armas y votos (Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes/CEREC, 1998); Eduardo

Pizarro Leongómez, "Bibliografia temática: Las fuerzas militares en Colombia (siglo xx)," Análisis Político No. 5 (Sept./Dec. 1988), 108-110; Eduardo Pizarro Leongómez,

"La reforma militar en un context de democratización política," in En busca de la estabilidad perdida: Actores políticos y sociales en los años noventa, ed. Francisco

Leal Buitrago (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo/IEPRI/Colciencias, 1995), 159-208; and William

Avilés, "Institutions, Military Policy, and Human Rights in Colombia," Latin American

Perspectives, Issue 118, 28:1 (Jan. 2001), 31-55.

52.. For information on these occurrences and an excellent analysis of the Colombian situation in the mid-1980s, see "The Central-Americanization of Colombia? Human

Rights and the Peace Process," An Americas Watch Report, January 1986.

53.. Leal Buitrago, "Surgimiento, auge".

54.. For a fascinating analysis of human rights discourse and its uses in Colombia, see Luís Alberto Restrepo M., "The Equivocal Dimensions of Human Rights in Colombia," in Violence in Colombia 1990-2000, ed. C. Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, 2001), 95-

126.

55.. See the Berkeley conference "Colombia in Context" (March 2001) website.

56.. Although the M-19 was influential in the constituent assembly of 1990, thereafter it lost political support rapidly and is not now a serious contender in

Colombian elections. See Lawrence Boudon, "Colombia's M-19 Democratic Alliance: A

Case Study in New Party Self-Destruction," Latin American Perspectives Issue 116,

28:1 (Jan. 2001), 73-92. Clearly guerrilla groups concerned with what will happen if peace negotiations are successful are very much aware of the somewhat divergent experiences of the M-19 and FARC's Union Patriótica. Political scientist David Close

24 is editing a book that compares the varied trajectories of guerrilla groups that enter democratic politics as political parties in Central America and Colombia.

57.. See Belisario Betancur, "Prologue", Eduardo Posada-Carbó, "Reflections on the

Colombian State: In Search of a Modern Role," and Manuel José Cepeda, "Democracy,

State and Society in the 1991 Constitution: The Role of the Constitutional Court," in

Colombia: The Politics of Reforming the State, ed. Eduardo Posada-Carbó (N.Y.: St.

Martin's Press, 1998), xiii-xxiv, 1-17, 71-96; Ana María Bejarano, "Perverse

Democratization: Pacts, Institutions, and Problematic Consolidations in Colombia and

Venezuela" (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2000); and Ana María Bejarano, "The

Constitution of 1991: An Institutional Evaluation Seven Years Later," in Violence in

Colombia 1990-2000, ed. C. Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, Del., 2001), 53-74.

58.. Although most observers maintain that the Colombian conflict is not ethnic or religious in character, Mary Roldan and Margarita Serje emphasize that regional imaginaries, which are also racial imaginaries, shape Colombian conceptualizations of place and government perceptions of danger and threat. See Roldan, Hegemony and

Violence, and Margarita Rosa Serje, "El revés de la nación: Los territorios salvajes en Colombia," paper presented at the conference "New Approaches to Social Conflict in

Colombia," University of Wisconsin, Madison, March 23, 2001. On the intersections of region and race in Colombia, see also Peter Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture: The

Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press,

1993); and Nancy Appelbaum, "Remembering Riosucio: Race, Region and Community in

Colombia, 1850-1950" (Ph.D. diss., University of Wisconsin at Madison, 1997).

59.. See Leon Zamosc, The Agrarian Question and the Peasant Movement in Colombia:

Struggles of the National Peasant Association, 1967-1981 (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1986; Leon Zamosc, "The Political Crisis and Prospects for Rural

Democratization in Colombia," Journal of Development Studies 25:4 (July 1990), 44-78;

Jesus Avirama, "The Indigenous Movement in Colombia," in Indigenous Peoples and

Democracy in Latin America, ed. Donna Lee Van Cott (New York: St. Martin's

Press/Inter-American Dialogue, 1994); Arturo Escobar, "Cultural Politics and

Biological Diversity: State, Capital and Social Movements in the Pacific Coast of

Colombia," in Between Resistance and Revolution: Cultural Politics and Social

Protest, ed. Richard G. Fox and Orin Starn (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers Unversity

Press, 1997), 40-64; Medofilo Medina, La protesta urbana en Colombia en el siglo veinte (Bogotá: Ediciones Aurora, 1984); Pearce, Colombia: Labyrinth; articles on paros cívicos in Revista Foro; Myriam Jimeno, "Movimientos campesinos y cultivos ilícitos. De plantas de dioses a yerba malditas," in La crisis socio-política colombiana: Un análisis no coyuntural de la coyuntura (Bogotá: Centro de Estudios

Sociales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia/Fundación Social, 1997), 343-354; Norma

Villareal Méndez, "Mujeres y madres en la ruta por la paz," in Ibid., 363-395; and, on the Colombian "Nunca Mas" project, "Colombia: Memory and Accountability," NACLA

Report on the Americas 34:1 (July/August 2000), 40-42.

60.. See, for example, Rodrigo Uprimny Yepes, "Violence, Power, and Collective

Action: A Comparison between Bolivia nad Colombia," in Violence in Colombia 1990-

2000, ed. C. Bergquist et al. (Wilmington, Del., 2001), 39-52; and Miguel Angel

Urrego, "Social and Popular Movements in a Time of Cholera, 1977-1999," in Ibid.,

171-78. Daniel Pécaut describes the social and psychological impact of terrorism and how the violence makes it virtually impossible for people to come together in

"Configurations of Space, Time and Subjectivity in a Context of Terror: The Colombian

Example," International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society, 14:1 (2000), 129-

25

150. For other takes on Colombian "civil society", see Mauricio Archila Neira,

"Tendencias recientes de los movimientos sociales," in En busca de la estabilidad perdida, ed. Francisco Leal Buitrago (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo/IEPRI/Colciencias, 1995),

251-301; Jesús Antonio Bejarano, "El papel de la sociedad civil en el proceso de paz," in Los laberintos de la guerra: Utopías e incertidumbres sobe la paz, ed.

Francisco Leal Buitrago (Bogotá: Tercer Mundo/ Universidad de los Andes, 1999), 271-

335; articles by Francisco Santos and Miguel Ceballos in Colombia: Conflicto armado, perspectivas de paz y democracia (Miami: Latin American and Caribbean Center, Florida

International University, 2001); Marco Palacios interview, Semana, April 9, 2001;

Salomón Kalmanovitz, "Colombian Institutions in the Twentieth Century," International

Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 14:1 (2000), endnote 34, p. 251; and Hector

Leon Moncayo S., "Una lectura crítica del discurso de los actores populares," Bogotá,

Planeta Paz, 2001, unpub. paper.

61.. Stimulating efforts to explore continuities and changes between the civil wars of the nineteenth century, the Violencia of the 1950s and present conflicts in

Colombia include Gonzalo Sánchez G., "War and Politics in Colombian Society,"

International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 14:1 (2000), 19-50; Malcolm

Deas, "Violent Exchanges: Reflections on Political Violence in Colombia," in The

Legitimization of Violence, ed. David E. Apter (N.Y.: New York University Press,

1997), 350-404; Charles Bergquist, "Waging War and Negotiating Peace: The