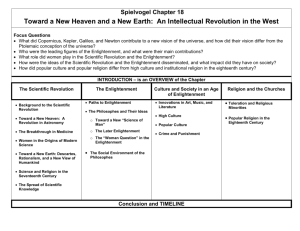

The Enlightenment and Science of Man

advertisement

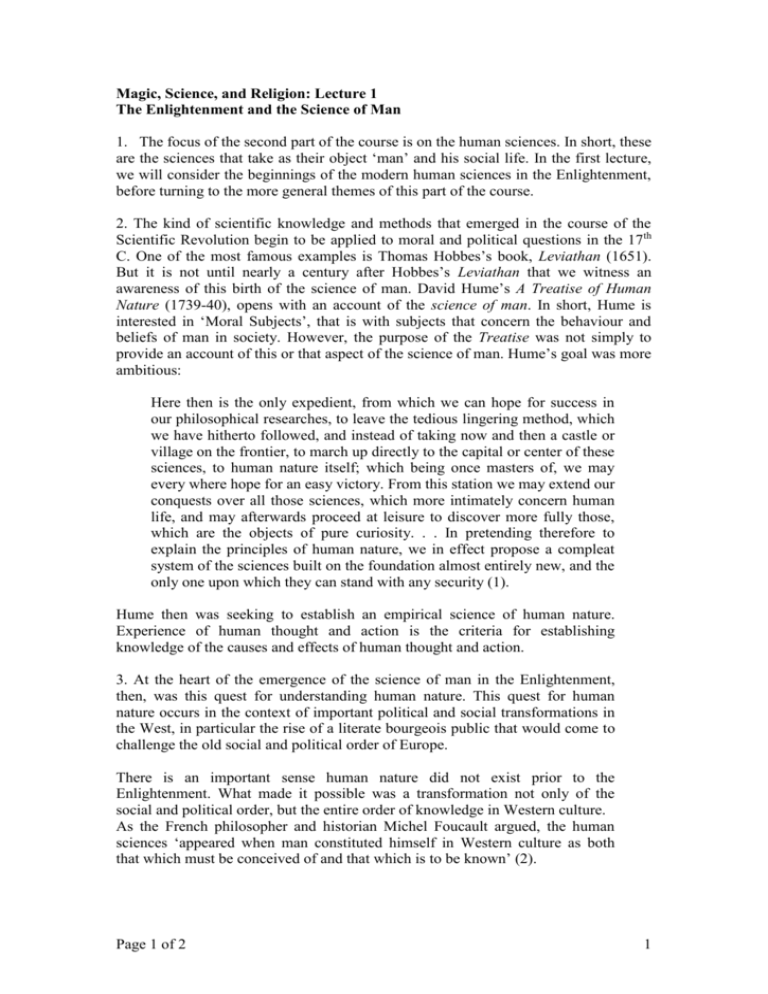

Magic, Science, and Religion: Lecture 1 The Enlightenment and the Science of Man 1. The focus of the second part of the course is on the human sciences. In short, these are the sciences that take as their object ‘man’ and his social life. In the first lecture, we will consider the beginnings of the modern human sciences in the Enlightenment, before turning to the more general themes of this part of the course. 2. The kind of scientific knowledge and methods that emerged in the course of the Scientific Revolution begin to be applied to moral and political questions in the 17th C. One of the most famous examples is Thomas Hobbes’s book, Leviathan (1651). But it is not until nearly a century after Hobbes’s Leviathan that we witness an awareness of this birth of the science of man. David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature (1739-40), opens with an account of the science of man. In short, Hume is interested in ‘Moral Subjects’, that is with subjects that concern the behaviour and beliefs of man in society. However, the purpose of the Treatise was not simply to provide an account of this or that aspect of the science of man. Hume’s goal was more ambitious: Here then is the only expedient, from which we can hope for success in our philosophical researches, to leave the tedious lingering method, which we have hitherto followed, and instead of taking now and then a castle or village on the frontier, to march up directly to the capital or center of these sciences, to human nature itself; which being once masters of, we may every where hope for an easy victory. From this station we may extend our conquests over all those sciences, which more intimately concern human life, and may afterwards proceed at leisure to discover more fully those, which are the objects of pure curiosity. . . In pretending therefore to explain the principles of human nature, we in effect propose a compleat system of the sciences built on the foundation almost entirely new, and the only one upon which they can stand with any security (1). Hume then was seeking to establish an empirical science of human nature. Experience of human thought and action is the criteria for establishing knowledge of the causes and effects of human thought and action. 3. At the heart of the emergence of the science of man in the Enlightenment, then, was this quest for understanding human nature. This quest for human nature occurs in the context of important political and social transformations in the West, in particular the rise of a literate bourgeois public that would come to challenge the old social and political order of Europe. There is an important sense human nature did not exist prior to the Enlightenment. What made it possible was a transformation not only of the social and political order, but the entire order of knowledge in Western culture. As the French philosopher and historian Michel Foucault argued, the human sciences ‘appeared when man constituted himself in Western culture as both that which must be conceived of and that which is to be known’ (2). Page 1 of 2 1 4. The birth of the human sciences then involves a search for what it is that unites all human beings, what essential characteristics and capacities they all share in common. But as the human sciences begin to develop distinct boundaries and objects, differences between human beings began to appear as objects of scientific inquiry. In particular, what we can see in the Enlightenment is the beginnings of empirical sciences concerned with accounting for cultural, national, and racial differences. The development of the human sciences in this direction was tied up with important assumptions and questions about the relationship of Western culture to the rest of the world. 5. By the end of the 18th C, ‘society’ itself had come to form an object of scientific knowledge (hence the ‘social sciences’) and was increasingly seen as being subject to laws of development and (moral) progress. This kind of history of society was designed to take society as its object, and account for the manifold differences that existed between men in different social contexts. At bottom, however, it turned on the Enlightenment science of human nature. 6. Over the course of the next seven lectures, we’ll consider how the Enlightenment science of man develops into various moments of the human sciences. More specifically, we’ll focus on the answers these sciences – mainly anthropology, psychology, and sociology – have offered to the kinds of questions and problems that arose in the Enlightenment. Thus in next week’s lecture, we’ll address theories of social evolution that attempted to account for the transition between various stages of human society, and more generally from primitive to civilised societies. In following weeks, we’ll consider how anthropologists and psychologists have accounted for the character of the primitive mind, and the social functions performed by religious and magical beliefs and practices. In the final two weeks, we’ll turn to perhaps the most famous account of the rise of the West and its uniqueness: Max Weber’s. References (1) Hume, David (1985), A Treatise of Human Nature. London: Penguin, p. 43. (2) Foucault, Michel (2002), The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge, p. 376. Page 2 of 2 2