Proof-reading

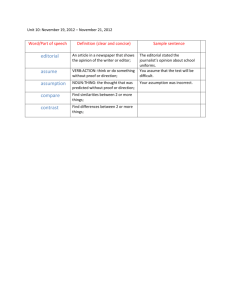

advertisement

Good Practice Guideline on Proof-Reading Introduction This good practice guideline was prepared by the plagiarism working group in 2007, and approved by UTLC in May 2007. It will be subject to period review. Background Learning from mistakes is one of the key ways in which student learning takes place. That principle applies to skills in expressing oneself in writing as much as it does to any other area. It also applies to the use of correct citation technique, a skill many disciplines place great emphasis upon. If submitted work has been substantially revised by a proof reader and/or the proof reader has made corrections to ensure correct citation, this does not help students improve their own skills and make them more employable, as it simply hides their shortcomings, rather than remedying them. The growth of professional proof reading services advertised to students is therefore a major concern. It is unrealistic to take the line that all proof reading is unacceptable. For instance spell checking is a form of proof reading that we advise our students to use. Furthermore checking for spelling and grammatical errors only would not be seen by many academics as a serious problem; modern computer software offers this service. Many students may ask friends to read through their essays and make comments, exactly what academics do with a draft paper intended for publication and read by colleagues, in order to seek general feedback or to have particular errors pointed out. It follows that unless the learning outcomes and assessment criteria for a particular module or degree explicitly preclude any proof reading beyond use of a spell check, proof reading that is limited to identifying errors in spelling, grammar and citation is in principle acceptable. After all this is what spell and grammar checking software does. However, in all cases, where proof reading starts to shade over into the proof reader actually undertaking the writing or re-writing of the whole or a part of the work, this is clearly unacceptable. The key principle relates to the role the proof reader plays, rather than to whether the proof reader is a professional or is paid for his/her services. If the proof reader has impact upon the content, structure or expression of ideas in what is written, that is unacceptable. There is thus a clear difference between proof reading which only identifies deficiencies and does not raise serious questions about whether the work is the student’s own, and proof reading which involves major rewriting and correction of the assignment. It has been suggested that students should be required to sign a declaration that the work submitted is their own and it would clearly be dishonest to sign this where a proof reader had done more than correct spelling and grammatical errors. If a proof reader has re-written the work, then it is not the student’s own work. However, knowing where to draw the line in practice is not easy. We might view proof reading as being on a continuum, at one of end of which are proof reading practices which all would accept as legitimate. At the other end are practices which all would agree are unacceptable. However, there is a considerable amount of disputed territory in the middle. No form of words can ever provide us with a watertight rule which can easily be enforced in any case. We cannot get away from the fact that in this area there will be difficult judgements to be made and that there will be practical problems in enforcement. However, there is still value in having a clear principle which is made known to staff and students alike. Guidance This matter needs to be decided on a case by case basis. The use of proof reading solely to highlight deficiencies such as spelling and grammatical errors, but with no impact on the content of the work, would normally be acceptable, as the work is still demonstrably the student’s. However, where proof reading goes beyond this to make corrections, improve the clarity of the argument, to alter content or to correct poor citation this is not acceptable, as the intellectual ownership of the work ceases to be the student’s. It is clearly unacceptable for such work to be submitted as the student’s own work and is demonstrably unfair. The above paragraph sets out a general principle. Academic staff may sometimes want to make explicit variations to this in relation to particular pieces of assessed work e.g. saying that no proof-reading at all is acceptable because the skill of writing is the key matter being assessed; allowing more substantial proof-reading support on an early formative piece of work on a programme with a large number of international students. Such exceptions must be made clearly and explicitly to students. It is important that students are advised in degree programme handbooks and other appropriate places about what in principle is and is not generally acceptable. Students should be encouraged to seek advice from their lecturer or seminar leader if they are in any doubt as to what is permissible. Disabled/Dyslexic Students Background Disability Support does not offer a proof reading service as such. However the Service does offer students 1:1 specialist support which is tailored to individual weaknesses and learning styles. This tuition develops academic skills and also general skills (such as time management and organisation). Within this specialist support an element of proof reading does occur. Students with dyslexia have problems expressing their ideas clearly in writing and tend to wander from the main point or fail to explain the point clearly and this is addressed by the tutor asking them to clarify what they are talking about. Exception for some disabled/dyslexic students An exception may need to be made where for example Disability Support identifies that a dyslexic student requires proof reading as part of a course of specialist multisensory tuition to develop literacy skills. During tuition students may be guided at times by the dyslexia tutor in order to clarify their arguments and explain these points, but only in so much that they are identifying their own deficiencies and correcting these themselves.