Park management - University of Colorado Boulder

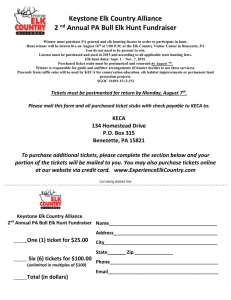

advertisement

Park management When nature goes too far Jan 1st 1998 | BIG HORN, WYOMING From The Economist print edition IN 1986 Alston Chase, a writer, stood before a piece of ground in Yellowstone National Park which had been grazed, as Mr Chase put it, “as smooth as a golf fairway.” He turned to a scientist. “Is this range damaged?” he asked. “What is truth?” the scientist replied rhetorically. “You and I look at this scene and see range damage. The Park Service sees nature at work.” As Yellowstone enters its 30th year of “natural regulation”, it finds itself in the middle of a deepening dilemma: should it go on letting nature take its course, or not? Critics have questioned natural regulation ever since its inception, and the policy now has fewer friends than enemies. When 800,000 acres—more than a third of the park— went up in smoke in 1988, patrons, furious at seeing wild fires left to burn, bombarded politicians, who then called for the head of the park superintendent, Robert Barbee. But similar storms erupted when nature was not left to regulate itself: 1,084 bison were shot during the winter of 1996-97 as they left the park looking for forage. A judge in Montana has just ruled, despite a petition from environmentalists, that they can be shot this winter, too. Now Yellowstone’s estimated 18,000 elk sit in the political spotlight. Park scientists once thought there could never be too many elk; there could be temporary overgrazing, but the range, they insisted, would spring back as soon as the elk died from starvation, revealing a natural equilibrium. This has not happened. The numbers at which the elk population would theoretically stabilise have kept rising, well beyond what the scientists predicted. Population ecologists such as Mark Boyce, of the University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point, say that winter and wolves will eventually take care of the problem. The cold and lack of feed that drove bison out of Yellowstone last winter also killed an estimated 6,000 elk. But wolves are a different story. They have killed about 360 elk since they were reintroduced to the park in 1995; on December 12th a federal judge ordered that, being a “non-essential experiment”, they should be removed again. Other scientists think the elks will not “internally regulate” their population before they have devastated vegetation in the park. Charles Kay, an assistant professor of political science at Utah State University, says the elk and bison in Yellowstone have become so numerous that they are destroying the habitat necessary to support a wide variety of animals, especially in an area called the Northern Range. Last February, Mr Kay produced (and showed to Congress) a striking series of photographs of different parts of the park at the turn of the century and now. These showed that, over the years, elk have stripped the park of its aspen and willow stands. Mr Kay claims that aspen in particular have suffered a 95% decline since the park opened in 1872: a serious development because beaver rely on aspen to build their dams, which in turn are vital to keep wetlands going. Park officials say that the elk are only partly to blame. In their view, a hotter and drier Yellowstone caused the moisture-loving willow and aspen to disappear. Mr Boyce says that Mr Kay’s pictures do not tell the whole story: although elk have been hard on these trees in some places, in others their impact is undetectable. And Mr Kay himself admits that aspen groves have been deteriorating throughout the west. The feeding of elk outside the park complicates the issue. Only two of the nine Yellowstone elk herds winter in the park. The rest migrate to feed. Herds in the southern end of Yellowstone head for the Jackson Hole Elk Refuge, where the state of Wyoming feeds each of them 3.5kg of hay a day. How can the numbers stabilise at a low level if they are fed? One biologist, Aldo Leopold, once flung up his hands at the folly of it all. “It seems to me academic,” he said, “to talk about maintaining the balance of nature. The balance of nature in any strict sense has been upset a long time ago, and there is no such thing to maintain.” Yellowstone, pulled and tugged by changing policy manuals and overbearing politicians, has a history of reactive management. When attacked by critics, the faithful tend to circle the wagons, only to capitulate as soon as some scientific school of thought convinces them that disaster is imminent. Yet that may change. Yellowstone is part of a new experiment in park fees. Last year the entry fee was raised to $20; the park will keep $8. Will visitors really pay to see dying elk and meadows nibbled down to the roots? Keeping part of the gate receipts may give the park more autonomy, and push politics further out of the picture. It would be even better if the park’s managers used their new freedom to come up with a consistent set of principles on which the park could be run.