The synthetic theory of addiction

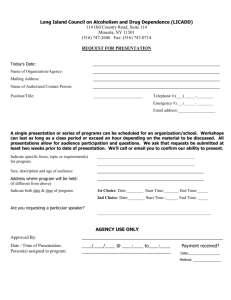

advertisement