The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)

advertisement

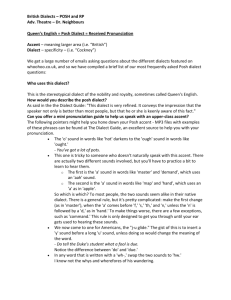

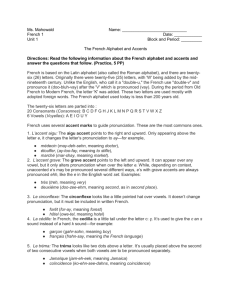

TEACHING ACCENTS AND DIALECTS TEACHING MATERIALS Jason Jones jjones@strodes.ac.uk 0 Investigating Language Variation Getting Started Brief: You are going to be conducting a short survey on the local High Street, with a view to finding out what factors people think have had the most significant influence on the way they speak. Your aim is to identify any significant patterns that emerge in the order in which your informants place the range of social factors that we have discussed in terms of how influential they have been on their speech. There will also be an opportunity for your informants to make observations about any influential factors that we have not yet considered. Method: In pairs, you must gather data from 12 informants as follows: Age 16-19: 2 male, 2 female Age 35-45: 2 male, 2 female Age 65+: 2 male, 2 female When you return to classroom you will pool your data with another pair of students. When you approach a potential informant, greet them with (a spontaneous version of) the statement below. Please remember that you are representing the College and must therefore behave in an appropriate manner: no chasing them down the street if they refuse to participate! Statement for informants: ‘We are English students at (SCHOOL/COLLEGE NAME) conducting a survey on the various factors that influence the way people use language. Would you mind answering a few brief questions for us please?’ Question 1 What factor has the most significant influence on the way that you speak (both pronunciation and the words that you use)? Question 2 Please look at the statements I am about to show you and place each of the statements into rank order to indicate the extent to which they are true for you as an individual (1 being the most true). Please add any explanations for your responses in the space provided. Please ensure that you put a number against each statement. Question 3 What feature or features of modern language usage annoy you the most? THANK YOU FOR YOUR TIME 1 Statement Order The area I have grown up and lived in has been the dominating influence on my speech. My social and family background has been the dominating influence on my speech. My friendship networks have been the dominating influence on the way I speak. Media such as TV, music and film have been the dominating influences on my speech. My work has been the dominating influence on the way I speak. My gender has been the dominating influence on the way I speak. My sexual orientation has been the dominating influence on the way I speak. My age has been the dominating influence on the way I speak. My ethnicity/race has been the dominating influence on the way I speak. 2 Explanation Regional Variation – Worksheet 1 The accent(s) and dialect(s) of your local area… and further afield (i) Using the outline map of the British Isles provided, draw the area which represents the geographical spread of the regional variety that is spoken in (NAME OF SCHOOL’S/COLLEGE’S LOCATION). Indicate as accurately as possible where you think the regional variety boundary should be drawn. Where, for example, do people begin to speak differently? Consult the county boundary map if you need to. (ii) Give your regional variety area a name and then, on a separate sheet, make a note of three or four of each of the following that seem typical of your dialect area: Ways of pronouncing individual words Particular rhythms or intonations over a number of words Words that are unique to this dialect Common words that have a different meaning in this area Grammatical and syntactic features that would be considered nonstandard elsewhere (iii) We’re going to start looking further afield now. Think about some of the other regional accents and dialects that you know from around the country as a whole. As you did in part (i) of this worksheet, draw the area covered by each of your chosen regional varieties on the map, then for each variety: identify someone in the public eye who uses this regional variety make a note of some linguistic features that are characteristic of the variety 3 (iv) 4 5 Regional Variation – Worksheet 2 The accent(s) and dialect(s) of the British Isles (i) Below are the popular names that are often given to the accents and dialects of a number of regions of Britain, together with the regions in question (jumbled up). Geordie Scouse Glaswegian Mancunian Brummie Cockney Glasgow East London Birmingham Newcastle Manchester Liverpool First of all, match the names to the regions. Next, on the second map you’ve been given, match each variety with the geographical locations pinpointed (A to F on the map) For each of the six varieties, try to think of three non-standard words and three nonstandard pronunciation features that are used in that area and write them in the box next to the variety plotted on the map. (ii) Now listen to the recordings of speakers from each of these areas and see if you can identify which is which. Which significant linguistic features helped you to identify each variety? Make notes in the table below Recording 1 Regional Variety Significant linguistic features 2 3 4 5 6 6 A: __________________ B: __________________ C: __________________ F: __________________ D: __________________ E: __________________ 7 Trudgill’s Regional Dialect Areas 8 Regional Variation – Worksheet 3 The accent(s) and dialect(s) of your local area - LEXIS For each of the pictures and questions below write down any non-standard words that people in your area would use. Don’t worry if there isn’t a non-standard word for a particular object/concept in your area – just leave the box blank. Similarly, if there is more than one non-standard word, write them all down. If you think a term is used only by a certain generation or by a particular group of people, indicate this in brackets. (1) What is one of these called? (2) What terms are used for LEFT-HANDED? (3) What do people in this area call their EVENING MEAL? (4) What do people in this area call someone who walks with their legs turned inwards or outwards? (5) What term is used for someone who is bad tempered? (6) What are these called? 9 (7) What do people in this area call the children’s game where one person is ‘it’ and has to catch the others? B (9) What does each of these men have growing on his cheeks? (8) What word would children say in the above game to give them temporary immunity from being caught? (10) What words do people in this area use for something that is GOOD? (11) What words do people in this area use for something that is BAD? (12) What words are used for people who move about from one place to another living in caravans and buses? 10 (13) What do these people have in common? They are all…. Regional Variation – Worksheet 4 The accent(s) and dialect(s) of your local area – GRAMMAR Indicate (using a tick or a cross) whether the following non-standard grammatical constructions are likely to be used by people living in your area. (1) I didn’t have no dinner yesterday. (2) My dad seen an accident on his way home. (3) My sister have a boyfriend and she see him every day. (4) That was the man what done it. (5) John fell over and hurt hisself. (6) Mary’s more nicer than her brother. (7) She spoke very loud. (8) Leave your things here while you come back. (9) Our teacher can’t learn us anything. (10) I want this coat cleaned. (11) I want this coat cleaning. (12) She gave it her friend. (13) Give it to me (14) Give it me. (15) Give me it. (16) I were going down the road. (17) We was going down the road. (18) If you’re tired, why don’t you lay down. (19) The water was dripping out the tap. (20) Will you go and buy me two pound of apples? (21) We never had TV in them days. On a separate sheet of paper identify in linguistic terms what is going on in each of these non-standard constructions. 11 Regional Variation – Worksheet 5 The accent(s) and dialect(s) of your local area – PHONOLOGY Transcribe (using the IPA or an agreed orthographic representation) the way in which people in your area would pronounce the following words: CUP PATHWAY LAST PALM NEEDY UPPER POOL HAPPY TOOTH FACE FARM WALKING TUESDAY BULL LIGHT CAR HANG HAT MILK BALL NEWS 12 The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) Consonants Key Sound IPA Key Word Sound IPA Word bee B rat R dog D sat S fog F ship SH gap G tip hat H chin CH yet Y thin TH (-vce) cap K this TH (+vce) led L van V map M wet W nap N zip Z song NG pat measure P gin T ZH J Some non-standard consonant sounds: Key Word Regional Variety 13 Sound IPA Vowels Key Sound IPA Key Word Sound IPA Word cup UH book U car AH spoon OO hat A time EYE UGH cow OW E go OH ER hair AIR I pay EH need EE hear EAR cot O noise OY tall AW sure OO-UGH agree hen churn pin Some non-standard vowel sounds: Key Word Regional Variety 14 Sound IPA The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) We transcribe the sounds of speech using the alphabet of the International Phonetics Association. The symbols we use are listed below, with an example of their use along side (their pronunciation being indicated by the underlined letter(s) in a given word). Consonants IPA Word bee IPA Word cap IPA Word rat IPA Word this dog led sat van fog map ship wet gap nap tip zip hat song chin measure yet pat thin gin Vowels IPA Word cup IPA Word churn IPA Word book IPA Word hair car pin spoon pay hat need time hear agree cot cow noise hen tall go sure 15 Regional Varieties Checklist When analysing regional dialect data, you should aim to comment (where possible) on the following features: (1) (2) Phonological features (i) Vowels What is the pronunciation of the vowels in words such as the following: mud, cup, hug etc. path, grass, laugh etc. palm, calm etc. hazy, happy, needy (final vowels) etc. pool, spoon, tooth etc. gate, hale, face etc. (ii) Consonants Is this a rhotic or non-rhotic variety – i.e. is the /r/ sounded in words such as bar, farm, birth etc? Are any consonants replaced with glottals? Which ones? Is this an /h/-dropping variety? How is word-final –ing realised? Does /l/ vocalisation occur? What is the distribution of clear and dark /l/? Is the /j/ sounded in words like few, news etc? Are there any occurrences of assimilation, coalescence or elision? Grammatical features (3) Verbs: Does the variety have any examples of non-standard present tense forms? What about past tense? Negation: Does the variety have any instances of multiple negation? Does the variety have any instances of ain’t? Nouns: Does the variety have any non-standard plural forms? Pronouns: Does the variety have any non-standard personal pronouns? What about relative pronouns? Adjectives: Does the variety have any non-standard comparative and/or superlative forms? Demonstratives: Does the variety have any non-standard forms? Adverbs: Does the variety have any non-standard adverb forms (e.g. standard English –ly adverbs without the –ly)? Prepositions: Does the variety delete any prepositions, or have any non-standard preposition usage? Lexical features Does the variety have any non-standard… Nouns? Verbs? Adjectives? Adverbs? Function words? Exclamations? Fillers? Terms of address? Word-meaning relationships? Do you notice any other non-standard lexical items? 16 Analysing Regional Varieties Below is a transcript of a speaker from Newcastle. He is about fifty years old, and has lived in this area all his life. His regional accent and dialect are consequently quite strong. First of all, read the transcript and make a note of any non-standard lexical, semantic, grammatical and syntactic features you can see. Then listen to the recording from which the transcript was made and comment on the non-standard phonological features you hear. Use the Regional Varieties Checklist as a guide to your analysis. I’ll tell you what, I often tell it at work. You know, they’d say to you, ‘Hey Jimmy, lend us a shilling man’. What? Lend us a shilling… me and I’d say to them come here a minute I’ll tell you. I says, I can remember when I used to shove a bairn about in a pram for a tanner a week. A lot of money a tanner then a week. And I says I’ve been pushed for money ever since, so they divn’t come back. Put them out the road. Wey lad, get away, go on. Aye, he says, for a tanner. By, you can do a lot with a tanner. You can gan to the pictures, get yoursel a penny fish and a haipeth of chips, by God, yeh, and maybes a packet of Woodbines for tuppence, and a match in, for to get your first smoke… bah… I once ge… remember getting some Cock Robins, called them Cock Robins, bah… they cock-robinned me, I’ll tell you. I was at Newburn Bridge… that’s it… you can see Newburn, it’s across there, and I was smoking away, faking, you know, instead of just going ph ph… swallowing down, you know, I was sick and turned dizzy. I didn’t know what hit us with these Cock Robbins… bah, but they were good uns. 17 The Talk of the Nation For this extended task, you will be working in small groups carrying out detailed research into the accents and dialects of specific parts of Britain. Each group will be working on a different regional variety allocated to you from the following list: West Country Wales West Midlands Yorkshire Northumbria Scotland Northern Ireland (Note that some of these areas are very broad, so you might come across variation within them) Each group will be given the following resources: A recording of a speaker using your allocated variety A basic orthographic transcript of this recording Copies of Talking for Britain by Simon Elmes (with one chapter focusing on your allocated variety) Your task is to: (i) RESEARCH thoroughly the origins, history and development of your allocated variety, and identify its distinctive phonological, lexical/semantic and grammatical/syntactic features (use ‘Talking for Britain’, other texts on your reading list and internet search engines for your research; use the ‘Regional Varieties Checklist’ for analysing the recording). (ii) PRESENT your findings to the rest of the class in the form of a PowerPoint presentation. Use my Liverpool presentation as a guide, but bear in mind that your section on origins etc. needs to go into the same depth that the ‘Routes of English’ CD did for Liverpool, rather than simply being a bullet point overview. You will also need specific sections on Phonology, Lexis/Semantics and Grammar/Syntax - use the sub-headings identified in (iii) below as a guide to structuring your presentation (iii) PRODUCE as an individual a written report on your findings. This report should include the following sub-headings: Origins, History & Development Transcript and analysis (here you should include an annotated copy of the transcript, together with an overview of the non-standard linguistic features present in the text) Phonology (an account of the distinctive pronunciation features of the variety) Lexis & Semantics (a dictionary-type word list, with definitions and examples of usage) Grammar & Syntax (an account of non-standard features). Deadline for final submission of individual written report: ______________________ 18 Internet signals end of an era for Yorkshire dialect By Ian Herbert Published: 04 July 2007 There was a time when every self-respecting Yorkshireman knew that an attercop was hard to find in blashy but not any more, according to the Heritage Lottery Fund, which commissioned research on the fast disappearing dialect of God's own county. The results of the research form an exhibition that has opened in the Dales Countryside Museum, in Hawes, Wensleydale, West Yorkshire. The project, which included college students recording conversations with men and women aged 18 and over, revealed that words commonly used in the Dales just two generations ago were now a mystery to many young people. Attercop, which, incidentally, translates as spider, and blashy, which means wet weather, have evidently long gone. "Unfortunately, the Yorkshire dialect is a bit sparse - the day could not be far off when we all use the same words wherever we come from," said Jo Cremins, the co-ordinator of the £20,000 project. Miss Cremins, who lectures in English at Craven College, in Skipton, West Yorkshire, added: "We asked people, for example, what they called a baby, or what word they used for tired. Many just gave us a peculiar look and said 'We call a baby a baby'. Fewer people are coming back with dialect words. People do still recognise dialect words, even if they don't use them themselves. They remember their parents or grandparents saying them, but that is transient because the next generation won't have heard them at all and the words will be lost." Miss Cremins, who was born in Yorkshire, believes there are two main reasons for the words vanishing from Yorkshire vocabularies - and the prime culprit is new media. "There is a worry now with the internet, texting and the media that things are becoming diluted and watered down," she said. "An international language is coming in, the sort of thing everybody speaks and can understand. "Words which were specific to individual communities are being lost because these communities are not as isolated as they once were. I don't think people stop using them because they are embarrassed by the possibility of not being understood - although there was a time when children were corrected and made to use the standard English word - but perhaps it's a desire to fit in, picking up what is used on the television and not wanting to stand out." She also blamed changes in the Dales way of life. "There's a whole farming vocabulary which has disappeared with mechanisation. Words which began life as farming terms and then got taken up into the general language have passed out of use. We have to work really hard to preserve this, but it is difficult as language is changing all the time." Recordings made by students of conversations using the vanishing words form part of the exhibition. "Listeners can hear them in context and perhaps understand better what the words mean," Miss Cremins said. "It's good that we can make them available for people to hear still, but whether they are used or not is a very different thing; usage is going." However, while the words might be vanishing, the distinctive accent Yorkshire people used to speak them is safe. "While some regional accents are derided, some people told us they put their accent on even more whenever they are away from Yorkshire," Miss Cremins said. "It is something to be proud of." 19 Arnold Kellett, of the Yorkshire Dialect Society, also believes dialect has been replaced by "local speech", which retains the accent and intonation of dialect but hardly any of the vocabulary. "Speakers of real, authentic dialect are an endangered species. Education - or lack of it, social and geographical mobility, electronic globalisation, the mediafication of language, the growth of rap and 'Estuary English' have taken their toll on traditional 'Broad Yorkshire'," he said. Disappearing words * Just as the South Yorkshire floods struck, blashy, a word for wet weather, disappeared. * Tykes are not prone to shows of flashiness which might explain why fufflement (showy clothes) has vanished. * The word yocken describes an activity relished for many a year before the word disappeared: to eat or drink with enjoyment. * It is surprising that a county allegedly famous for penny-pinching should not take this activity seriously but addle - to earn - has also gone. 20 Wed 21 Feb 2007 Brothers put in a geed wyord to save an ancient Scottish dialect from extinction JOHN ROSS Two brothers in eighties may be last speakers of unique dialect Distinct Cromarty dialect has died out with the fishing industry Academic plans to record 'most threatened dialect in Scotland' Key quote "I think other people understand it, but they don't use it. You don't hear the expressions we used to use at all now, but I think that's true for everywhere. - BOBBY HOGG Story in full WHEN Bobby and Gordon Hogg meet up for a chat, they enter a linguistic world that few, if any, can now understand. The brothers, both in their eighties, may be the last known speakers of a dialect peculiar to the Black Isle town of Cromarty. Robert Millar, a lecturer in linguistics at Aberdeen University and author of Northern and Insular Scots, has described the dialect as the most threatened in Scotland. With Bobby, 87, and Gordon, 80, perhaps the last practitioners, efforts are being made to record their distinctive twang as part of the Highland Year of Culture. The small communities throughout the Black Isle once had five separate dialects, with the fishing people of Cromarty, Avoch and Fortrose each having their own distinct speech. On the web www.ambaile.org.uk www.britannica.com The brothers' fishing dialect is even different from that spoken in the main part of Cromarty, which is derived from Scots. Bobby said: "It's been dying for some time and it will just die a natural death. I was brought up in the fishing industry, which has died out, and the dialect has gone as the place changes. "It was not used by the people very much, although my brother and I speak it all the time. Others gave it up because they maybe thought it was not the right way to speak. "I think other people understand it, but they don't use it. You don't hear the expressions we used to use at all now, but I think that's true for everywhere. "You can hear the odd smattering of it in some of the things people from Cromarty say, but nobody really speaks it." 21 The fishing language still uses formal expressions such as "thee", "thou" and "thine", and words beginning with "wh" can often lose the "h" or even "wh". The phrase "what do you want?" is heard as "at thee seekin?" Bobby's wife, Helen, said: "My husband is fluent in the Cromarty fisher dialect. I understand it, but his brother is the only other person who can speak it." Jamie Gaukroger, the content coordinator at Am Baile, the online Highland culture archive, said he hoped to record the brothers in the next few days to help preserve the dialect. "I was not aware until last week that there was this distinctive Cromarty dialect. It's new to me, but it's very exciting all the same," he said. "It's important that we get it recorded while we still can. If we manage to get it on tape before it disappears, it will be a real coup." David Alston, a Cromarty-based historian and local councillor, said: "There were two distinct dialects in Cromarty, the town dialect and the fisher dialect. "But the fisher dialect has now almost completely gone - Bobby and his brother and perhaps only a couple of others are the only ones left." Mr Alston said language was dynamic, with new dialects emerging all the time. "There is a natural process of dialects dying and coming to be, but it is important we record them before they disappear," he said. SOUNDS UNIQUE ACCORDING to the Scottish National Dictionary, the Cromarty dialect has some distinctive sounds. When a "g", or "k" precedes a vowel, the "oo" sound can be replaced by "ee". So, for instance, good, school and cool become geed, skeel and keel. When the vowel comes before an "r", as in ford, moor and poor, the word can be changed to fyoord, myoor and pyoor. The "wh" sound at the start of words is often replaced by a "wu" - so which and whiskers become wutch and wuskers. In words where "kn" is pronounced "n", this can change to "kr" - knee, knife and knit are heard as kree, krife and krit. An "h" is often inserted or omitted from the beginning of words. So ale-house, Annie, hand and house become hile-us, Hannie, an and oos. 22 Sat 5 Aug 2006 Wullie's still oors and not English MIRIAM MEYERHOFF RECENT reports suggesting the imminent death of Scots may, as the saying goes, be exaggerated. The study (conducted in Germany) concluded that over the years, the language used in Oor Wullie has become more anglicised. In other words, more English words and spellings are being used and less of the Scots forms or alternate spellings that represent Scottish pronunciations. But in fact, it may just be that Oor Wullie's keeping up with the times. Linguists take for granted the fact that language changes. Speakers who are not professional linguists understand this too. For example, most speakers of Edinburgh English could give you several examples of words that have changed in their lifetime. Slang goes in and out of fashion; sometimes a word sticks around but its meaning changes. Sociolinguists make an art of studying the patterns underlying language variation in a community, and in particular they are interested in how social trends affect language use in a community. It has become clear differences in pronunciation within a community today are what become the language change of tomorrow. Changes to Oor Wullie's language, like the different pronunciations you hear on the streets of Edinburgh, may be markers of social changes taking place in the larger community. And they don't necessarily herald the loss of a distinctive dialect. For sure, you can hear pronunciations or phrases being used in Edinburgh, especially among younger speakers, that seem to be "English". The frequency of what some linguists call "th-fronting" -- bruvver instead of brother, mouf instead of mouth, somefink instead of the traditional Scots somehin' or something probably has spread to Edinburgh from southern English. And it's possible that the less frequent use of the distinctively Scots doon and oot is also the result of the northward spread of southern English varieties. But before we start to lay the blame for all of this at the door of Edinburgh's ten per cent English-born population (and in some parts of town it is considerably higher than that), we need to understand that it's not just the English. North American varieties offer another source for language change. The increased use of like, especially to introduce speech - "What did your parents say about how late we got in?" "Mum was wild. She was like 'I had no idea where you were!'" - almost certainly originated in North America. And there is a significant, but highly mobile, population of Australian and New Zealand English speakers who come to work in Edinburgh. But do these changes mean Edinburghers are sounding less Scots? Not really. The forms I have mentioned (doon and oot; somefink; she was like) are ones that are socially very significant. They are what sociolinguists call linguistic stereotypes. Like other kinds of stereotype, a linguistic stereotype is one that people trot out as a quick way of imitating or summing up the characteristics of a group of speakers. But most of the variation in speech happens well below this level of awareness. In other words, people don't realise they are doing it and they don't have strong stereotypes about which groups of speakers use these forms more or less. Sociolinguists call these markers, and it's the markers that really define a dialect. For instance, most of the Scots vowel system isn't changing towards southern English norms. All those fronted vowels typical of the south-east (the ones that make younger speakers sound as though they never open their mouths or are talking through their noses)? You don't hear them in Edinburgh. Even if Oor Wullie may be 23 becoming "Our" man in the comics strips, Edinburghers don't use the fronted pronunciation of "our" (something like "ee-wa") that they use in the south. Something distinctively local remains. That relaxed vowel at the start of "Willie" ("Wullie")? Alive and well throughout the central belt. The widespread pronunciation of words like walking, following as walkin, followin continues. And what's interesting is that some of these markers are relatively recent and some have persisted for centuries. The Wullie vowel is probably no more than four or five generations old. But the walkin pronunciation has been the norm in Scottish English for centuries. It may be historically and socially one of the most successful local acts of resistance to southern English norms - Scots speakers of all social classes here have been using it for hundreds of years. Oor Wullie's changing with the times, like all speakers of Scots English. But it would be a mistake to think that that necessarily means he's sounding more English. Like most speakers, it seems more likely that he's taken what's out there, ditched the old vocabulary and picked up a few new sounds, but he'll be using them with distinctive local colour. Miriam Meyerhoff is professor of sociolinguistics at Edinburgh University 24 You are what you speak By Joe Campbell BBC News 28 March 2007 The UK's regional accents are changing - and it's not just the spread of Estuary English behind this shift, but the slang and intonation of Caribbean and Asian voices. Let me start by declaring an interest: I've lived in London for 15 years and know the city as well as any local. But as soon as I open my mouth, it's obvious that like the most recently arrived Polish plumber, I'm not from round these parts, as they say in Greater Manchester, where I was born. Even my four-year-old son can spot it: "It's glahss - not glass, Daddy," he helpfully points out. I may have moved south, but like my former neighbours who chose to stay in the north of England, I've steadfastly refused to accept the advance of the elongated southern vowels that remain the most recognisable indicator of where your roots lie in the UK. As the British Library launches its Sounds Familiar website to help a growing number of youngsters studying our linguistic differences, I cannot help but feel a stubborn pride in resisting the rising tide of so-called "Estuary English" that has spread out from London across southern half of the country. Am I bovvered by its spread? Many are. But perhaps all is not what it seems, says Jonnie Robinson, the man behind a British Library scheme to get a new generation of speakers to contribute to an online collection mapping the way we speak. "I'd accepted the line you usually hear that dialects and accents are disappearing," he says. "Yes, things are changing as they always will, but the diversity is still as wide as it ever was." True, some of the old regional accents have been pushed out. Mr Robinson cites that of the entertainer, Pam Ayres, whose distinctive voice many would place as coming from somewhere in the South West. In fact, recordings in the British Library's archive show it as typical of rural Berkshire where she was born 50 years ago - just a half hour's drive from Heathrow Airport on the western edge of London. That accent, and the received pronunciation of the Royals encamped at the other end of Berkshire in Windsor Castle, may be rare. But in Reading, between these two extremes, there's a new accent with influences from Commonwealth immigrants from the Caribbean and Indian sub-continent. 25 "Those cultures are leaving their mark on the language just as the Viking settlers did when they dominated Yorkshire hundreds of years ago," says Mr Robinson. "What we're hearing are wonderful new voices with vowel sounds from places like Jamaica and Asia mixed with more familiar accents. Take the boxer Amir Khan. If you close your eyes and listen, it's obvious he's an Asian lad. But at the same time he couldn't be from anywhere other than Lancashire." LISTEN IN British Library has put 5,500 recordings of accents and dialects online English Language including study of accents Among the first to contribute to the British Library's new site are from Holy - is fastest growing A-level Cross Sixth Form College, just down the road from the gym in Bury in subject greater Manchester, where the Olympic medal winning boxer used to train. Received pronunciation or BBC English - is a Say 'bus' minority accent spoken by They are among the 35,000 teenagers studying at any one time for an A-level no more than 2% of people in English language, which involves work on accents and different patterns of speech. It's the fastest growing course at that level. 26 British accents in the US From the mouths of teens A 'perfect storm' of conditions has seen teen slang from inner-city London spread across the country. But where does this new language originate from? And, if you can't stop kids from speaking it, is there any way to decipher what the words mean? Published: 05 November 2006 At the back of a London bus, two teenagers are engaged in animated conversation. "Safe, man," says one. "Dis my yard. It's, laahhhk, nang, innit? What endz you from? You're looking buff in them low batties." "Check the creps," says the other. "My bluds say the skets round here are nuff deep." "Wasteman," responds the first, with alacrity. "You just begging now." The pair exit the vehicle, to blank stares of incomprehension. Later, this dialogue is related to Gus, a 13-year-old who attends an inner London comprehensive; he wastes no time in decoding it. ''Safe just means hi,'' he says briskly. "Your yard is like your home, where you're from. Nang just means good. Your endz is your neighbourhood. Buff is, like, attractive. Low batties are trousers that hang really low on your waist. Creps are trainers. Bluds are your mates. Skets are sort of slutty girls. Nuff means very. Deep is the same as harsh or out of order. Wasteman is what you say to someone when you're fed up with them. And begging," he concludes, with a flourish, "means chatting rubbish." There's more: butters means ugly, hype is excitement, bare is a lot, cotching is hanging around, and allow it is a plea to leave something or someone alone. "Everyone in my school speaks like this," says Gus, a little wearily. "It's because you hear the cool kids saying these words and then you have to do it too. You've got to know them all and you've got to keep up. Nobody wants to be uncool," he adds, with a shudder. " That's, like..." Sick? "No, sick is good," he says patiently. "I guess it would just be, you know, deep." Gus and his ilk have been caught up in an emerging linguistic phenomenon. Researchers have found that, while most traditional cockney speech patterns have followed traditional cockneys as they've migrated out to Essex and Kent and other points beyond the M25, teenagers in inner London, one of the world's most ethnically diverse areas, are forging a separate multi-ethnic youth-speak based on common culture rather than ethnic or social background. Multiculturalism may have become a political hot potato for everyone from Daily Mail leader writers to Trevor Phillips, but anyone passing a metropolitan playground will realise that, linguistically at least, the melting-pot patois is already a reality from Tooting to Tower Hamlets. "It is likely that young people have been growing up in London exposed to a mixture of second-language English and varieties of English from other parts of the world, as well as local London English, and that this new variety has emerged from that mix," says Sue Fox, a language expert from London University's Queen Mary College, who's in the middle of a three-year project called Linguistics Innovators: The Language of Adolescents in London, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. Fox and her colleagues have studied the speech patterns of a sample of teenagers across the capital. "One of our most interesting findings," she says, "was that we'd have groups of students from white Anglo-Saxon backgrounds, along with those of Arab, South American, Ghanaian and Portuguese descent, and they all spoke with the same dialect. But those 27 who use it most strongly are those of second or third generation immigrant background, followed by white boys of London origin and then white girls of London origin." The dialect is heavy with Jamaican and Afro-Caribbean inflections; words are clipped, as opposed to the cockney tendency to stretch vowels (thus face becomes fehs, as in "look a' mi fehs"), and certain words - creps, blud (thought to relate to blood, as in brother) and sket, are Jamaican in origin. This has led some in the media to invoke Ali G and Radio 1 DJ and " wigga" Tim Westwood, and dub the patois Jafaican, though Fox points out that Indian, West African, and even Australian slang (nang is an Aussie term, as is dag, meaning uncool) are just as much in evidence, as are new variants - saying raaait in lieu of right, for instance - whose origin remains obscure. "The term Jafaican gives the impression that there's something fake about the dialect, which we would (omega) refute," she says. "As one young girl who lives in outer London said of her eight-year-old cousin who lives in inner London, 'People say he speaks like a black boy, but he just speaks like a London boy.' The message is that people are beginning to sound the same regardless of their colour or ethnic background. So we prefer to use the term Multicultural London English (MLE). It's perhaps not as catchy," she says, "but it comes closer to what we're trying to describe." In the half-century since teenagers first came of socio-cultural age as a distinct demographic, their relationship to the rest of society can be described as a tense stand-off punctuated by howls of hormonal turbulence. " Don't laugh at a youth for his affectations," said the US essayist Logan Pearsall Smith. "He is only trying on one face after another, to find a face of his own." Over the years, the faces have included provocations ranging from skinheads to hoodies, but the advent of MLE is believed to mark the first time that teenagers have consciously used language to stake out their own territory ("I can't understand a word he's saying sometimes," bemoans Gus's mother, in perfect following-the-script style). Professor Paul Kerswill of Lancaster University, who is leading the Linguistics Innovators study, believes it's no accident that teenagers should be the early adopters of MLE. "Adolescence is the life stage at which people most willingly take on new visible or audible symbols of group identification," he says. " Thus, fashions specific to this age group change rapidly. Fashion and music often go together, and these in turn are often associated with social class and ethnicity. The same is true of language. It's most obviously observable in terms of slang and new ways of expressing themselves, such as the substitute of 'I'm, like' for 'I said' or 'I thought' a few years ago." (This was the most blatant manifestation of RisingInterrogative Valley-Girl speak - as in "I'm, like, so over him? But he's, like, totally bugging me?" - that was the preferred lingua franca among teenage girls before the rise of MLE). "What we're seeing with MLE is qualitatively different," continues Kerswill. "It's a real dialect rather than simply a mode of speech, and there's already evidence that it's spreading to other multicultural cities like Birmingham, Bristol and Manchester. It'll become more mainstream through force of numbers and continued migration, and because it's considered cool." Kerswill and his fellow researchers believe a "perfect storm" of circumstances has arisen to ensure the rapid dissemination of MLE: a nexus of immigration, population mobility, and a wave of successful London garage stars (and MLE speakers) such as Lady Sovereign and Dizzee Rascal. The face of MLE could well be MIA, a Sri Lankan-born rapper raised on an estate in Hounslow, west London; her single Galang contains the refrain "London calling, speak the slang now". "You can hear this music on a national basis," says (omega) G Money, a DJ at 1Xtra, the BBC's urban radio station. "It's not something you have to search for on the pirate networks any more. And it's definitely having an influence. I was in Watford recently and the kids there were no different to the ones you see in London. They all dress the same and they all speak the same." The rise of MLE is happening at a time when Kerswill and his team are seeing a general trend across the UK toward dialect levelling - the process whereby people in different parts of the country sound more and more like each other as their local accents and dialects die out and everyone, from the Prime Minister downwards, speaks 28 a form of elided-vowel Estuary English. " Dialect levelling is strongest in new towns such as Milton Keynes" says Kerswill. "Local accents - what we call dialect solidarity - tend to s urvive in close-knit communities, most of which are working class. It's interesting, for example, that Liverpool seems to be getting more scouse. Population make-up would be a factor, as well as what some linguists would call 'neighbour opposition' with its arch-rival Manchester. It's a question of identity." Kerswill believes that levellings versus solidarities will have a bearing on the future of MLE. Concerns have already been raised about its ubiquity, with the Lilian Baylis School in Kennington, South London, banning the patois as part of a government pilot project to improve results. "We're not trying to devalue it," says Gary Phillips, the school's head. " We're trying to teach the kids that its time and place is not in the standard English world of formal essays or debates." But the crunch for MLE could come when its adherents move out of their close-knit teen community and enter the dialect-levelling world of adulthood. "We don't quite know whether kids will un-acquire MLE as fast as they've picked it up," concedes Kerswill. "The indications are that it depends very much on people's social networks and aspirations. Those who go into university or highly-paid jobs will change their speech. Those who remain where they are will most likely retain a lot of it. Most people are doubtless somewhere in the middle, and will change to some extent. But that will open the way for MLE to lead to changes in the English language in its spoken form, at least. One conclusion that we have definitely drawn from this study," he concludes, "is that English is one of the most dynamically protean of all languages." Back at the sharp end of the socio-linguistic coal-face, Gus would have to agree. "The words change all the time," he says wearily. " It's, like," (even in his out-of-school Standard English, he pronounces this "laaahhhkk") "you have to learn a whole new vocabulary every few months just to keep on top of it. It's like, just recently, swag now means bad." And that's not nang? "Allow it," he proclaims, switching effortlessly into standard MLE. "It's all getting bare swag." 29 It's the way that you say it Recordings in a new online archive provide a unique sound map of spoken English John Crace Tuesday April 3, 2007 The Guardian Posh is posh, right? Well, yes and no. Take the royal family, the apotheosis of the refined upper classes. Listen to the Queen and then notice how different her speech is from her grandson's. The Queen has a very clipped, stiff-upper-lip delivery, while Prince William uses much more modern pronunciation. And yet no one would hesitate to label them both posh. Somehow language, accent and dialect manage the curious duality of being both fluid and static at the same time; whatever changes may take place, the speaker is still instantly geographically, culturally and socially identifiable. This paradox is the starting point for a new online archive, Sounds Familiar, launched this week by the British Library. Made up of recordings from the 1950s Survey of English Dialects and the 1999 Millennium Memory Bank, Sounds Familiar incorporates more than 600 audio-clips to create a unique sound map of spoken English, past and present. "Some of the oldest recordings are of men and women who were in their 80s in the 1950s," says Jonnie Robinson, curator of english accents and dialects at the British Library, "so it's like hearing an echo from the past. We also have a real mix of cultures, regions and generations, which allow us to chart the variations and changes in vocabulary, pronunciation and grammar through time." False alarm Language doesn't always change in the way we might think. Not so long ago some academics argued that estuary English (or non-standard southern English, as linguistics experts prefer to call it) was, thanks to TV shows such as EastEnders, slowly taking over the whole country and that some northern accents - particularly Glaswegian - were being diluted. But Robinson points out that this latest version of the imperialist south has turned out to be a false alarm. "There is no doubt the London dialect we have come to call estuary has spread out across the southeast," he says, "but research has shown that northern accents and dialects have withstood its spread. Language is a great deal more robust than we imagine." Even so, language does change - even if the process is often very slow. Some of the old dialects of the south - particularly those of Oxfordshire, Sussex and Berkshire have all but disappeared - and you have to travel much further west from London these days to come across similar rural vowel sounds. So what accounts for the shifts? "Population upheaval is the principal contributory factor," says Robinson. "The spread of estuary across the south-east has coincided with increasing numbers of Londoners moving further away from the centre of the city. The almost overnight transformation of small villages into large, new towns, such as Milton Keynes, was bound to have a huge impact on speech patterns." Cultural perceptions also influence language. Academics have noticed that many young women in Yorkshire have changed their vowel sounds in certain words; instead of Cooca Coola, they now say Cerka Curla - simply because they imagine the new accent to be posher. "All accents and dialects come with certain preconceptions," says Clive Upton, professor of modern English language at Leeds University. "Some rank high on intelligence and low on friendliness and humour. As a general rule, it appears accents from the big conurbations are considered less desirable." He rejects a standardised 30 objective viewpoint - "Locating call centres in Scotland has far less to do with the perception of a trustworthy accent than with the relative cheapness of property and labour" - arguing that it's our own internal dialogue that largely determines our reactions. "If you ask foreigners to rate our regional accents and dialects against benchmarks of trustworthiness and intelligence," he says, "you get very different responses to native British people. This is because they don't have the same cultural baggage as we do." They do, of course, have their own cultural baggage and this in turn raises interesting questions about the future of English and the way it is spoken. English has morphed into world English, with more speakers on the Indian subcontinent than in England, the US, Australia, Canada, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand combined. So the English we might wish to consider a global standard for pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar is, in reality, just a minority dialect. Immigration has also had a marked impact on the diversity of language - with African-Caribbean and Asian accents merging with indigenous English dialects to create new hybrids. Listen to Amir Khan, the teenage boxer who won a silver medal at the Athens Olympic, and he is both identifiably Asian and from Bolton. How lasting any of these new voices will be is another matter. Many white kids have adopted an Ali G-style African-Caribbean accent to mark them with street cred, but it is impossible to predict whether its appearance is ephemeral or permanent. "Ideas of social prestige change," says Robinson. "Back in the 1920s and 30s , many people assumed that the very middle-class, received pronunciation in which the BBC insisted presenters speak would survive indefinitely as the dominant accent. It was the broadcasting voice of the nation, and anyone who aspired either to get on the BBC - or to be seen as someone of that social class tried to speak like that. But now that way of speaking is considered old-fashioned and is rarely heard, especially among the young." Trends come and go, but genuine shifts in language are relatively rare, with the last major change in this country being the great vowel shift of the 14th and 15th centuries, which signified the change from middle to modern English. Words such as "hoose" became house - though traces of the old middle-English pronunciation still survive in the north - and no one knows precisely why. The most popular theory is that it coincided with mass immigration to the south-east after the Black Death and the need to standardise pronunciation amid a mass of different vowel sounds. Texts reflect local dialects Without recordings - Florence Nightingale is the oldest famous voice in the archive - linguistic scholars have to rely on forensic evidence to theorise how language was spoken at any given time. Prior to a standardised spelling, texts such as the Bible would be written in a way that reflected the local dialect, so the geographical location of a book would give pointers to pronunciation. As ever, though, analysis reveals as much about how much has stayed the same as how much has changed. "There is still a clear dividing line between the language that is spoken in west Yorkshire and that in the north and east," says Upton, "and this reflects the limits of the Viking influence. " Language evolves for many reasons - even something as superficial as the hegemony of supermarkets, as any Midlander trying to buy a pikelet will tell you. In Sainsbury's it's a crumpet or nothing. But change is not something to be judged or mourned; it's something to be observed and understood. The purpose of the website is to document the history of language - with schools and universities invited to become part of the process by sending in their own regional recordings. As Upton says, "We're not in the business of preservation. The only language that doesn't change at all is a dead one." 31 Regional Varieties in Literature (1) In the famous graveyard scene from Hamlet, Shakespeare makes some clear linguistic distinctions between the lowly gravediggers (here called ‘clowns’) and Prince Hamlet: 1 CLOWN: 2 CLOWN: 1 CLOWN: 2 CLOWN: 1 CLOWN: Is she to be buried in Christian burial, that wilfully seeks her own salvation? I tell thee, she is: and therefore make her grave straight: the crowner hath sat on her, and finds it Christian burial. How can that be, unless she drowned herself in her own defence? Why, ‘t is found so. It must be se offendendo; it cannot be else. For here lies the point: if I drown myself wittingly, it argues an act, and an act hath three branches: it is to act, to do, and to perform: argal, she drowned herself wittingly. ________________ HAMLET: To be, or not to be, that is the question:Whether ‘t is nobler in the mind, to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune; Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? – To die, - to sleep, No more:- and, by a sleep, to say we end The heart-ache, and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to, - ‘t is a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d… (2) In D.H.Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the working class background of the gamekeeper Mellors is mirrored by his broad East Midlands speech, while Lady Chatterley’s use of a standard linguistic variety indicates her elevated social position. This is implicit in the speech of each of these characters throughout the novel, but in the following extract Lawrence draws greater attention to the social distance between the two lovers by emphasising the specific differences between their respective uses of language: “Tha mun come one naight ter th’ cottage, afore tha goos; sholl ter?” he asked, lifting his eyebrows as he looked at her, his hands dangling between his knees. “Sholl ter?” she echoed, teasing. He smiled. “Ay, sholl ter?” he repeated. “Ay!” she said, imitating the dialect sound. “Yi!” he said. “Yi!” she repeated. “An’ slaip wi’ me,” he said. “It needs that. When sholt come?” “When sholl I?” she said. “Nay,” he said, “tha canna do’t. When sholt come then?”… He laughed. Her attempts at the dialect were so ludicrous, somehow. “Coom then, tha mun goo!” he said. “Mun I?” she said. “Maun Ah!” he corrected. “Why should I say maun when you say mun?” she protested. “You’re not playing fair”. 32 (3) We can see this technique being used much more recently in J.K.Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. In the extract below, the language used by Rubeus Hagrid, essentially a working class character who is a bit ‘rough around the edges’, is represented through unconventional spelling. On the other hand, Vernon Dursely, a company director who lives in middle class suburbia, speaks in a very formal manner: There was a crash behind them and Uncle Vernon came skidding into the room. He was holding a rifle in his hands – now they knew what had been in the long, thin package he had brought with them. ‘Who’s there?’ he shouted. ‘I warn you – I’m armed!’ There was a pause. Then – SMASH! The door was hit with such force that it swung clean off its hinges and with a deafening crash landed flat on the floor. A giant of a man was standing in the doorway. His face was almost completely hidden by a long, shaggy mane of hair and a wild, tangled beard, but you could make out his eyes, glinting like black beetles under all the hair. The giant squeezed his way into the hut, stooping so that his head just brushed the ceiling. He bent down, picked up the door and fitted it easily back into its frame. The noise of the storm outside dropped a little. He turned to look at them all. ‘Couldn’t make us a cup o’ tea, could yeh? It’s not been an easy journey…’ He strode over to the sofa where Dudley sat frozen with fear. ‘Budge up, yeh great lump,’ said the stranger. Dudley squeaked and ran to hide behind his mother, who was crouching, terrified, behind Uncle Vernon. ‘An’ here’s Harry!’ said the giant. Harry looked into the fierce, wild, shadowy face and saw the beetle eyes were crinkled in a smile. ‘Las’ time I saw you, you was only a baby,’ said the giant. ‘Yeh look a lot like yer dad, but yeh’ve got yer mum’s eyes.’ Uncle Vernon made a funny rasping noise. ‘I demand that you leave at once, sir!’ he said. ‘You are breaking and entering!’ ‘Ah, shut up, Dursley, yeh great prune,’ said the giant… …Uncle Vernon suddenly found his voice. ‘Stop!’ he commanded. ‘Stop right there, sir! I forbid you to tell the boy anything!’ 33 Regional and Social Variation: The Relationship You may have observed that people who belong to the highest social classes tend not to have a particularly ‘broad’ regional accent and dialect, or, at least, they don’t have a variety that can be easily identified as belonging to a particular region. Standard linguistic forms are used throughout Britain, with little variation. As we move further down the social scale, we find greater regional variation. This situation is illustrated by the two ‘cone’ diagrams below. Figure 1 represents social and regional variation in dialects (grammar and lexis only), while Figure 2 represents social and regional variation in accents (pronunciation). Both diagrams emphasise the point that it is impossible to separate regional and social variation: they are two sides of the same coin. In Figure 1, the most prestigious variety is standard English, and in Figure 8.2 Received Pronunciation has the most prestige. Figure 8.1 shows that speakers at the top of the social scale (i.e. at the top of the ‘cone’) speak standard English with very little regional variation; any variation that is apparent will usually occur between two (or more) equally standard forms. For example, he’s a man who likes his beer or he’s a man that likes his beer are both acceptable forms in standard English, and it is quite likely that it will be speakers’ regional backgrounds that dictate which form they use. But the further down the social scale we go, the greater the regional variation, so that we encounter additional forms such as he’s a man at likes his beer, he’s a man as likes his beer, he’s a man what likes his beer, he’s a man he likes his beer and he’s a man likes his beer (after Trudgill, 1983a: 29–30). Each of these is a non-standard form and each belongs to a different regional variety. The same pattern of variation can be seen in lexical items. WC, lavatory and toilet are all acceptable in standard English, and all refer to the same thing. But bog, lav, privy, dunny and John are all non-standard words for the same object, and are not only features of lower social varieties, but also can be categorised in terms of regional usage. Figure 2 represents variation in pronunciation. The main difference between the two diagrams is that there is no regional variation in the accent used by the speakers of the highest social class. This is why we see a point at the top of the ‘cone’, rather than a plateau. This means that speakers at the top of the social scale tend to pronounce their words with the same accent (i.e. RP) regardless of their regional background. But, as with dialect variation, the further we move down the social class scale, the greater spread of regional pronunciation we find. 34 social variation regional variation Fig. 1: Social and regional variation in dialects social variation regional variation Fig. 2: Social and regional variation in accents Text reproduced from Jones, J. ‘Language and Class’ in Thomas, L & S. Wareing Language, Society and Power 35 Love the accent? Stephen Fry says British actors have it easy in the US because Americans are impressed by the accent. Rubbish, says Toby Young - these days, it's only talent that counts Wednesday March 21, 2007 The Guardian 'I have come here to rook the Americans, to make money and to have a good time," wrote Cecil Beaton when he first arrived in New York in 1928 - and, according to Stephen Fry, nothing has changed. In this week's Radio Times, he complains that his fellow countrymen have succeeded in bilking the American entertainment industry out of hundreds of millions of dollars simply by speaking in "veddy Briddish" accents. "I shouldn't be saying this - high treason, really - but I sometimes wonder if Americans aren't fooled by our accent into detecting a brilliance that may not really be there," he says. "Would they notice if Jeremy Irons or Judi Dench gave a bad performance?" There's nothing new in this complaint. As someone who has lived in both New York and Los Angeles, I heard it on an almost daily basis (though usually from my American hosts rather than a fellow limey). In Bonfire of the Vanities, for instance, Tom Wolfe took aim at the upper-class Englishmen who had infiltrated New York society, comparing them to vultures. "One had the sense of a very rich and suave secret legion that had insinuated itself into the cooperative apartment houses of Park Avenue and Fifth Avenue, from there to pounce at will upon the Yankees' fat fowl, to devour at leisure the last plump white meat on the bones of capitalism," he wrote. But is it true? New Yorkers may have been impressed by Cecil Beaton's accent in 1928, but would it open doors in 2007? Are Americans still so credulous that they fall at the feel of any Tom, Dick or Harry who says "tom-ah-to" rather than "tom-eh-do"? In my experience, this particular cliche is long past its sell-by date. Planeloads of freeloading British hacks - not to mention the three million British tourists who visit the country every year - have poisoned that well. On first hearing an English accent 50 years ago, Americans might have thought: stately home, private school, good manners. Nowadays, they think: low income, poor diet, alcohol problem. Take my own adventures as a single man in New York. On one occasion I was at a party on the Upper East Side when I found myself talking to a beautiful young heiress. I'd been trying to impress her by chastising Americans for misusing certain English words - and, God help me, it seemed to be working. She stood before me, open-mouthed in amazement. "Can you say that again?" she asked, after I had pointed out that "snogging" is the English equivalent of "sucking face" not "knocking boots". I happily obliged, at which point she beckoned her friend over: "Hey, Mary-Ellen, come check this out. This guy has English teeth." Needless to say, "English teeth" is not something Americans ask for when they visit their orthodontists. It is not even true, as Stephen Fry seems to think, that an English accent is an advantage when it comes to landing acting jobs. Admittedly, several British actors have enjoyed huge triumphs recently on American television shows, most notably Minnie Driver in Riches, Dominic West in The Wire and 36 Ian McShane in Deadwood. But they are all playing Americans - so their success can hardly be attributed to their British accents. It may also be true that Hollywood casting agents still look to us when it comes to playing villains. In 2006 releases, for instance, Bill Nighy was cast as Davy Jones in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, Ian McKellen played Magneto in X Men: The Last Stand (as he has in the series) and Clive Owen was a bank robber in Inside Man. But in most cases that come to mind, the actors were playing non-English characters so, again, Stephen Fry's point doesn't apply. If you ask any British actor why we still occupy this niche, he will tell you that it is because playing a nasty character is a lot harder than playing a nice one. When I put the question to Alan Rickman (German terrorist, Die Hard; American doctor, Something the Lord Made), he said: "It's because we can act, dear boy." So who, exactly, is Fry thinking of? He singles out Judi Dench, and it is true that she has played British characters in her last five films: Notes on a Scandal, Casino Royale, Mrs Henderson Presents, Pride & Prejudice and Ladies in Lavender. But, then again, those are all British films. Not much evidence of American gullibility there. The only actors Fry can legitimately point to in order to corroborate his thesis are people like Jane Leeves, Ashley Jensen and Dominic Monaghan - all of whom have been cast as British characters in American TV shows. Still, it's worth bearing in mind that the characters they play all speak in regional accents, not the traditional, BBC accents that Fry appears to be thinking of. After all, it is unlikely that an American casting director would be fooled into "detecting a brilliance that may not really be there" after hearing Jane Leeves speak. (She played Daphne Moon in Frasier.) The only exception I can think of is Dougray Scott (Ian Kavanaugh in Desperate Housewives) but nor is he really an example of the phenomenon of which Fry complains, since he is a Scot playing an Englishman. If he is capable of playing an English toff - and wasn't to the manner born - then hats off to him. Without wishing to sound too uncharitable, could Fry's curmudgeonly remarks have anything to do with the success of Hugh Laurie, his former acting comedy partner? Laurie has been garlanded with awards for his portrayal of an American neurosurgeon in House, a show for which he reportedly receives £240,000 an episode. Now that Laurie is enjoying Dudley Moore-like success across the Atlantic, is Fry turning into Peter Cook? (As Cecil Beaton's biographer, Hugo Vickers, wrote: "Cecil found it hard to forgive success in others.") Luckily, Fry has recently enjoyed some kudos himself playing a psychiatrist in Bones, an American crime series. Let's hope he bucks the trend, overcomes what is clearly the enormous handicap of having an English accent and goes on to match his former partner's success. 37 Give us charisma not class, say British bosses 1 April 2005 British bosses have turned their backs on the posh upper class accent in favour of a bubbly personality, according to latest research. In fact, almost half (49 per cent) of UK company directors and senior managers believe that a plummy accent is now a hindrance rather than a help when it comes to succeeding in business. Anti-accent attitudes were high on a hit list revealed by the Aziz Corporation, one of the UK’s leading independent executive communications consultancy. Neutral accent Indeed having a working-class accent was considered even worse, with 86 per cent of those who took part in the survey feeling it is a disadvantage in business. 64 per cent of businessmen believe that in fact a neutral accent is a strong advantage. While the diversification of different accents, both upper and working class, in the media has helped bridge the class divide to some degree, it is clear from the research that the business world puts more emphasis on personality than how posh someone is. Having a cheerful and upbeat manner or a good sense of humour are thought to be a strong advantage by 74 per cent and 54 per cent of businessmen respectively. Effective communication Professor Khalid Aziz, Chairman of The Aziz Corporation, said: 'The days when merely speaking with "the right accent" was a prerequisite to rising in the business world are now all but gone, although being an effective communicator is still paramount. 'The rise of Britain’s self-made men, often from working-class backgrounds, such as BHS boss Philip Green or Ryanair’s Michael O’Leary reflects the changing profile of the successful boss. 'These are people who aren’t afraid to speak their minds, and are proud to make a virtue of the fact that they have worked their way up from humble beginnings to positions of influence. In both cases though, they are better known for their forceful and charismatic personalities than for their class origins.' Old-fashioned He added: 'Conversely, one only has to think of the way that a person with a fairly plummy accent, like Boris Johnson, is portrayed in the media to understand that the impression created is of someone who is rather bumbling and quaintly old-fashioned. 'These are not the attributes associated with business acumen. The Duke of Wellington may have thought that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, but today’s business leaders were clearly educated elsewhere. 'The modern business environment is clearly not as class-riddled as our society remains, and it is interesting to note that being perceived as working class is every bit as bad as being seen as posh. 'It is therefore much more important that business leaders have a powerful personality, humour and presence. Being classless in business merely allows these other, more valuable, qualities to shine through.' 38 Parents' regional accents may harm children By Graeme Paton Last Updated: 12:00am GMT 25/03/2007 Being raised by a Scottish mother and an English father is always going to cause a few problems - most of them linked to football. But now it is feared that confusion over which national team to follow may be the least of a child's worries. Academics believe that children may fall up to two years behind in reading and writing at school if their parents have different regional accents. A study reveals that babies as young as five months recognise and react differently to the word patterns and stresses associated with accents. Dr Caroline Floccia, a lecturer in language development at Plymouth University, said: "If children are presented with two very different sound systems they will have to work that little bit harder to develop something in the middle - that is going to have an impact on their ability to learn language." Researchers tested up to 300 toddlers in a specially developed "Baby Lab". Infants were placed in sound booths to see how they responded to recordings of adults with North American and English accents reading a bland text. Researchers said babies were particularly responsive to the pitch of the English accent, regularly turning their heads towards the sound source. "Children from five months can distinguish a British accent from an American accent," said Dr Floccia. "It is said that if a child is bilingual and it is exposed to two different tongues they're behind, perhaps by two years in reading and writing at school. "We want to see if the same is true for children who have exposure to regional accents at home." Further research is being undertaken by Plymouth University. Dr Floccia said that children's development may be slowed, suggesting teachers should be informed to accommodate any delays in reading or writing ability. 39 When it comes to comedy, accents are key Sam Jones Monday August 21, 2006 The Guardian Like so many things in life, being funny would seem to be something of a postcode lottery. However, a team of boffins has trawled the country to discover how different accents influence how comical we find a person. After asking 4,000 people to listen to the same joke in 11 different regional accents, researchers from the University of Aberdeen concluded that the Brummie accent, as typified by the likes of Frank Skinner, Jasper Carrott and Lenny Henry, is Britain's funniest, appealing to more than a fifth of those questioned. The Scouse accent took second place, while the lilting tones of Geordies came third with 14.3% of the vote. The Mancunian and Glaswegian accents fared less well, respectively tickling the funny bones of 2.1% and 3.4% of those polled. Languishing at the bottom of the list was received pronunciation. The clear, rootless accent once favoured by BBC broadcasters, appealed to just 1.1% of participants. The study also discovered that accents perceived as warm were deemed funnier than apparently cold ones, and that Cockney patter was particularly suited to risque humour. Dr Lesley Harbidge, the comedy expert who led the research, chose a test joke which reflected the traditions of British stand-up comedy and which forced the listener to concentrate on the teller's pronunciation rather than their apparent cleverness. The researchers found that the three funniest accents - Brummie, Scouse and Geordie - were also deemed to be the least intelligent. 40 Talk Like a Brummie Day About How often do we hear or read this on a slow news day? “The Brummie accent has been named the least intelligent” “least trustworthy” “least friendly” “most dishonest”? When the media needs a quick stupid stereotype what sort of voice do they pick? Well us moaning isn’t going to change anything - let’s face it we’re bloody good at whinging and it hasn’t worked yet - so we should celebrate our accent and dialect and encourage everyone to ‘Talk Like a Brummie’ for one day. We hope you’ll help and build up helpful tips on perfecting the accent as well as links to existing dictionaries and collections of Brummie. You can leave your own favourite Brummie phrases or words in our ‘dictionary‘. Special events are planned and will be announced on our blog nearer the time, although anyone wanting to organise their own event - readings of Brummie poetry, bands or singers that use Brummie, whatever - is encouraged to, particularly Brummie expats in other towns or cities around the UK. Send us an email and we’ll add them here. Come July 20th we’ll be celebrating, no matter how dark it gets over Bill’s mothers. (extract from www.talklikeabrummieday.co.uk) 41 Attitudes to Linguistic Variation Non-standard Varieties Tolerance Survey Ask people you know in three age groups (under 20, over 40, over 60) whether they consider the following non-standard usages acceptable or unacceptable. Keep a tally of your responses and compare your results with those of other students in the group. (1) That reply is different to what I expected (2) We bought some flowers off the market stall (3) Me and Mary went out last night (4) Try and arrive early (5) They invited my friends and myself (6) She doesn’t actually dislike computer games – she’s just disinterested in them (7) It looked like it would rain (8) Everyone must sign their exam entry form (9) He promised to action the plan immediately Now ask your informants if there are any other words, phrases or general uses of language that annoy them. Make a note of their responses below. 42 Attitudes to Regional Varieties – Worksheet 1 Getting Started Activity 1 Think about your own attitudes towards different accents and dialects of British English. Do you have a favourite? What about a least favourite? Do you find a particular accent friendly/authoritative/sexy etc.? Make a note of your answers in the boxes below. Favourite Variety Reasons Least Favourite Variety Reasons Activity 2 Read the following statements, which have been collected by various researchers looking into language attitudes. Try to explain the linguistic and/or sociolinguistic basis for each of these views (e.g. comment number (1) is clearly based on phonological features, while comment number (2) apparently goes deeper than that, pointing towards certain sociolinguistic issues). (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) ‘Lancashire people speak in a warm way; the Yorkshire accent is more blunt’ ‘I lost my job because of my Birmingham accent.’ ‘Why can’t the BBC use Queen’s English speakers like they used to?’ ‘Our GP has a strong working-class accent. My mum doesn’t like it.’ ‘Cockneys sound very cheerful when they talk.’ ‘Cockneys sound disrespectful to everything.’ ‘I wish I didn’t have a local accent’ ‘Oh I really like yours – can’t stand mine though.’ ‘It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman despise him.’ (George Bernard Shaw, 1912) ‘I wouldn’t trust anyone with a Scouse accent.’ ‘I’ve got to be honest – if I had to choose between employing someone with a southern accent or someone from the north, the southerner would win hands down.’ ‘You should hear his language – you can tell what sort of person he is.’ ‘When I mark essays, I insist on different from, not different to.’ ‘Brummies sound miserable all the time, don’t they.’ ‘I don’t care if he’s got a PhD in Astrophysics – a Welshman still sounds thick.’ ‘I really love a Scottish accent.’ ‘Yeah – apart from Glaswegian. You can’t understand a word they say, and they all sound like headcases.’ 43 Attitudes to Regional Varieties – Worksheet 2 Measuring Attitudes (1) You are about to hear a number of different speakers talking about a variety of topics. While listening to the speakers, fill in the chart below, giving your own response to the following questions: (i) Where is the speaker from? (ii) How would you describe the speaker’s character? (iii) What social class do you think the speaker belongs to? (Use Working Class, Middle Class and Upper Class) (iv) What sort of job do you think the speaker might have? (v) Overall, how impressive do you find the speaker? (Give them a mark out of 10, where 1 = unimpressive and 10 = impressive) Speaker Where from? Character/personality Social class 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 44 Job Impressiveness score Attitudes to Regional Varieties – Worksheet 3 Measuring Attitudes (2) You are about to hear a number of different people talking about a variety of topics. While listening to each person, please rate them for each of the personal characteristics listed below, using a five point scale as follows (example for ‘intelligent’): 5 = VERY INTELLIGENT 4 = INTELLIGENT 3 = NEITHER INTELLIGENT NOR UNINTELLIGENT 2 = UNINTELLIGENT 1 = VERY UNINTELLIGENT Speaker 1 Intelligent Sincere Self confident Friendly Well educated Reliable Career-oriented Easy going 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 Speaker 2 Intelligent Sincere Self confident Friendly Well educated Reliable Career-oriented Easy going Speaker 3 Intelligent Sincere Self confident Friendly Well educated Reliable Career-oriented Easy going Speaker 4 Intelligent Sincere Self confident Friendly Well educated Reliable Career-oriented Easy going 45 Reading List Bauer, L. & P.Trudill (1998) Language Myths (ISBN: 9780140260236) Chambers, J.K. (1995) Sociolinguistic Theory (ISBN: 0631183264) Chambers, J.K. & P.Trudgill (1998) Dialectology (ISBN: 0521596467) Cockcroft, S. (2001) Language and Society (ISBN: 0340780991) Coupland, N. & A.Jaworski (1997) Sociolinguistics: A Reader and Coursebook (ISBN: 0333611802) Elmes, S. (1999) The Routes of English (ISBN: 190171019X) Elmes, S. (2005) Talking for Britain (ISBN: 0141022779) Foulkes, P. & G.Docherty (1999) Urban Voices (ISBN: 0340706082) Hudson, R.A. (1996) Sociolinguistics (ISBN: 0521565146) Garrett, P., N.Coupland & A.Williams (2003) Investigating Language Attitudes (ISBN: 0708318037) Hughes, A., P.Trudgill & D.Watt (2005) English Accents and Dialects (ISBN: 0340887184) Milroy, L. (1987) Observing and Analysing Natural Language (ISBN: 0631136231) Montgomery, M. (1995) An Introduction to Language and Society (ISBN: 0415072387) Penhallurick, R. (2003) Studying the English Language (ISBN: 0333727401) Roach, P (2000) English Phonetics and Phonology (ISBN: 0521786134) Thomas, L. & S.Wareing (2004) Language, Society and Power (ISBN: 041530394X) Upton, C., S.Sanderson & J.Widdowson (1987) Word Maps: A Dialect Atlas of England (ISBN: 0709954093) Upton, C. & J.Widdowson (1996) An Atlas of English Dialects (ISBN: 0198692749) Upton, C., J.Widdowson & D.Parry (1994) The Survey of English Dialects: The Dictionary and Grammar (ISBN: 0415020298) Wells, J. (1982) Accents of English (1) (ISBN: 0521297192) Wells, J. (1982) Accents of English (2) (ISBN: 0521285402) 46