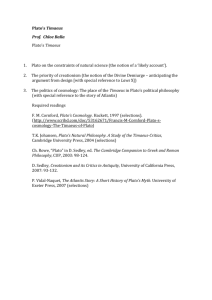

Mansfeld_05Illuminating

advertisement