Aztec – 1200CE – 1500CE Political – Outstanding warriors

advertisement

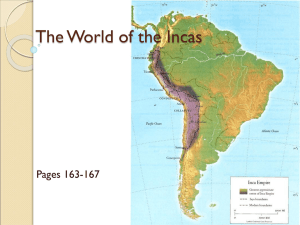

Aztec – 1200CE – 1500CE Political – 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Outstanding warriors, controlled most of modern day Mexico Monarch (single ruler) – similar to a king or queen Ruler said to have been related to gods to justify their control Slavery of conquered peoples Elaborate system of roads 6. Social – 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Several different classes – rulers, nobles or elites, farmers, and slaves Women and Men had different roles in society Women did have some rights, they could own property, work outside the house Slavery of conquered peoples Polytheism – religion that involved many gods Practiced Human Sacrifice as part of religion to make the gods happy, which often involved the consumption of human hearts 7. Mayan – 300 CE -900 CE Political – 1. City-States that were often at war with each other 2. Cities of near or over 100,000 people 1. Slaves used for Human Sacrifice to strike fear into their enemies 2. Rulers claimed to be related to gods to justify control 3. Sophisticated writing systems used to write many advanced books 4. Social – 1. 2. 3. 4. Several classes in society, mostly made up of farmers Human Sacrifice as a way to make gods happy Polytheism Advanced Calendar 5. Inca 1200 CE – 1535 CE Political1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Empire was around 12 million people before their decline All men required to serve in the military Army of over 200,000 members Well organized empire divided into 4 sections each with a governor Each of those sections was divided into provinces, who had lesser governors that ruled them Elaborate road system with bridges (even suspension bridges) 7. Social – 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Different roles for men and women Lots of farming in rural areas Irrigation systems that allowed very successful farming Elaborate architecture Polytheism System of record keeping called quipu that allowed for a very accurate record of supplies, military size and movement, and food. Had public theater, along with poetry and music Mayan Calendar: Anthony Engelward, Harvard University We made it! Given that you are reading this then it appears that the dire warnings about the end of the world occurring on December 21, 2012, did not come to pass. Congratulations, humanity! As almost everyone is aware (to the point of which certain government agencies felt the need to reassure people that the end is not nigh) we have been warned that the world will end as a result of a major turning point in the ancient Mayan Long Count Calendar. This concern was similar to people’s fears related to our modern calendar’s “turning the page” on January 1, 2000. But of course that was a fear about how our computer systems would “feel” about that particular calendar event, and fortunately many of them didn’t seem to mind too much. Mathematics of counting days In fact there is some interesting mathematics behind this particular calendar event. And given that you have lived through this catastrophe, perhaps you and your students might want to ponder the math behind this. It’s a good way to gain more of an appreciation of our Hindu-Arabic Base 10 positional number system (which many of us take for granted). We are all quite used to our classic base 10 counting system, where the position of each of the 10 digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 specifies its value in a typical number. For example, in the number 3,111 the digit 3 has a value quite different from its value in the number 1,131, representing 3 thousands in the first, and just 3 10’s in the second. It’s part of the “magic” of our modern positional system. Things progress orderly by powers of 10: 3 then 30, then 300, all represent 10-fold increases as the digit 3 passes from the 1’s to the 10’s to the 100’s position. Mayan number system In the Mayan Long Count calendar, days were counted, starting with the supposed creation of the world of humans (a bit over 5,000 years ago). In typical Mayan number systems, instead of counting with base 10, the count was done essentially with a base 20 system. Instead of positions going up 10-fold, they increased 20-fold. Thus the numbers 3, 30, and 300 represented 3, then 3 times 20, then 3 times 20 times 20, or simply 3 times 400, which is 20 squared. In Mayan counting 123 didn’t mean one 100, two 10’s, and and three 1’s. Rather, it meant one 400, two 20’s, and three 1’s (that would be 443 in our usual base 10 system). This is called a vigesimal (or base 20) system, as opposed to our decimal (base 10) system. Question: Why did they use 20 digits? And likewise, why did we settle on 10? Answer: Most likely it has to do with our fingers (10 of them). And probably it’s the case that some earlier cultures included their toes as well (20 fingers and toes). Perhaps this happened more often in warmer climates where toes were more likely to be exposed. Go to another planet with intelligent life forms, and they very likely will be counting using entirely different bases. Another quick question: how many digits did the Mayans need? Answer: They needed symbols representing 20 different possible digits instead of our 10 “Hindu-Arabic” digit symbols. These show up in Mayan stone carvings for calendar dates using pictographs (in other places they are represented with dots and bars). Description of Tenochtitlan, Capital of Aztec Empire, Written by Hernan Cortes to King Charles V of Spain – 1520 CE This great city of Tenochtitlán is built on the salt lake, and no matter by what road you travel there are two leagues from the main body of the city to the mainland. There are four artificial causeways leading to it, and each is as wide as two cavalry lances. The city itself is as big as Seville or Córdoba. The main streets are very wide and very straight; some of these are on the land, but the rest and all the smaller ones are half on land, half canals where they paddle their canoes. All the streets have openings in places so that the water may pass from one canal to another. Over all these openings, and some of them are very wide, there are bridges. . . . There are, in all districts of this great city, many temples or houses for their idols. They are all very beautiful buildings. . . . Amongst these temples there is one, the principal one, whose great size and magnificence no human tongue could describe, for it is so large that within the precincts, which are surrounded by very high wall, a town of some five hundred inhabitants could easily be built. All round inside this wall there are very elegant quarters with very large rooms and corridors where their priests live. There are as many as forty towers, all of which are so high that in the case of the largest there are fifty steps leading up to the main part of it and the most important of these towers is higher than that of the cathedral of Seville. . . . This city has many public squares, in which are situated the markets and other places for buying and selling. There is one square twice as large as that of the city of Salamanca, surrounded by porticoes, where are daily assembled more than sixty thousand souls, engaged in buying and selling; and where are found all kinds of merchandise that the world affords, embracing the necessaries of life, as for instance articles of food, as well as jewels of gold and silver, lead, brass, copper, tin, precious stones, bones, shells, snails, and feathers. There are also exposed for sale wrought and unwrought stone, bricks burnt and unburnt, timber hewn and unhewn, of different sorts. There is a street for game, where every variety of birds in the country are sold, as fowls, partridges, quails, wild ducks, fly-catchers, widgeons, turtledoves, pigeons, reed-birds, parrots, sparrows, eagles, hawks, owls, and kestrels; they sell likewise the skins of some birds of prey, with their feathers, head, beak, and claws. There are also sold rabbits, hares, deer, and little dogs [i.e., the chihuahua], which are raised for eating. There is also an herb street, where may be obtained all sorts of roots and medicinal herbs that the country affords. There are apothecaries' shops, where prepared medicines, liquids, ointments, and plasters are sold; barbers' shops, where they wash and shave the head; and restaurateurs, that furnish food and drink at a certain price. There is also a class of men like those called in Castile porters, for carrying burdens. Wood and coal are seen in abundance, and braziers of earthenware for burning coals; mats of various kinds for beds, others of a lighter sort for seats, and for halls and bedrooms. Incan Road Systems and Bridges, and their Explanations – McEwan, Gordon F. "The Incas." Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. Gale World History In Context. 2008. (Dec. 25, 2010) http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/whic/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?displayGroupName=K12Reference&action=e&windowstate=normal&catId=GALE%7C00000000MXFC&documentId=GALE%7CCX3078902877&mode=view&userGrou pName=nypl&jsid=951e4d5478fcfc18078c553f155149e7 McEwan, Gordon F. "The Incas: New Perspectives." ABC-CLIO. 2006. The Incas, of course, didn't invent the road -- that honor would no doubt go to the Romans -- but they did invent a network of roads and highways that connected their territory on a scale never seen before in South America. At its peak, the Incan highway system covered nearly 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) with roads that ranged from 3 to 13 feet (1 to 4 meters) in width and consisted of everything from simple dirt paths to passageways covered in fine paving stones. The network had main thoroughfares known as the imperial highway system, or Capac-Nan. These roads ran on a more or less north-south trajectory, with one hugging the coastline and another running roughly parallel through the mountains. Smaller roads connected the two main arteries with all of the provincial centers of the empire. The entire system was reserved for government officials; if you were a commoner, you needed to seek special permission to walk the Capac-Nan. Official business parties could travel approximately 20 miles (32 kilometers) per day along the Capac-Nan [source: McEwan]. Resting stations known as tampus were located along the roadways at approximately the same distance to offer travelers food, lodging and a chance to resupply. Rest was critical for these groups -- especially for the men whose shoulders carried nobles on raised platforms known as litters. The Incan empire's system of roadways not only satisfied the smooth workings of business and military maneuvers, it also functioned as a highly efficient communication network. Runners known as chasqui were stationed along the roads at approximately 0.9-mile (1.5-kilometer) intervals. These runners could verbally convey messages across the empire or even deliver small items. It was estimated that the system could function at approximately 150 miles (240 kilometers) a day, which allowed an emperor stationed at the eastern side of the empire to have fresh fish delivered to him in under two days from the Pacific Ocean nearly 250 miles (400 kilometers) away In the rugged, gorge-filled terrain of the Andes Mountains, there are places where roads alone would fail to provide adequate transportation. But, as was the case with most obstacles they encountered, the Incas had a solution: bridges. Unlike the arched stone bridges built in Europe at the time, the Incas used rope to construct suspension bridges across mountain chasms, as they had long been experts at weaving materials from natural fibers. Since there were no wheeled vehicles, the rope bridges worked beautifully for foot traffic, conveying both man and beast with ease. During bridge construction, large rope cables were formed from smaller ropes woven from llama and alpaca wool, as well as from grass and cotton. These were attached to stone structures on either side of the crossing. More of the thick cables were stretched to form handrails as well as the floor of the bridge, which was then covered with wood and sticks. Longer than any stone bridge in Europe at the time, the Incan bridges spanned openings of at least 150 feet (46 meters). Travelers often crossed in the morning, as strong winds later in the day could cause the bridges to swing wildly like hammocks. Because the materials that created the bridges were organic and biodegradable, they had to be rebuilt every year. Often, communities living near the bridges carried out this function. Map of Incan Road systems. In total it is estimated there were around 25,000 miles of road, enough to circle the entire earth at its widest point