What is a sustainable livelihood?

advertisement

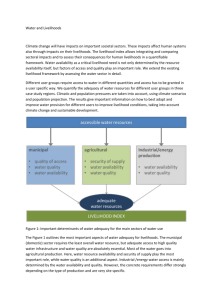

Sustainable rural livelihoods: a summary of research in Mali and Ethiopia Rosalind Goodrich July 2001 INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Brighton, Sussex BN1 9RE England Contents Introduction 1 The problem the research sought to analyse 1 Summary of results and conclusion 2 Livelihood diversification Agricultural intensification Migration 2 3 4 The intellectual approach 4 What is a sustainable livelihood? 5 Livelihood resources 6 The idea of a livelihood portfolio 7 The influence of institutions and organisations 7 Operational implications of the framework approach to analysis of sustainable livelihoods 8 The settings of the research 8 Research methods 9 How do poor rural households construct a sustainable livelihood? 12 Economic diversification Geographical location Who diversifies – the rich or the poor? Livelihood diversification and the development of local and wider markets Are livelihoods becoming more diverse and if so, why? How do household development cycles and livelihood diversification opportunities interact? The role of institutions in determining livelihood diversification Opportunities and outcomes 12 Agricultural intensification 16 Migration 20 How does policy influence livelihood strategies and can poor people influence the policy process? A model of how policy affects livelihoods Can poor people influence policy? Pursuing a policy-centred approach Annex 1 Research reports from the sustainable livelihoods research programme Annex 2 Livelihoods Connect – www.livelihoods.org Annex 3 Other references 22 22 23 24 Sustainable rural livelihoods Introduction This report summarises the results of research which explored alternative routes to achieving more sustainable livelihoods in two countries: Mali and Ethiopia. Research on the same topic in Bangladesh will not be discussed here. The work took place over a period of three years and was a joint enterprise between the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex (IDS), the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), the Poverty Research Unit at the University of Sussex, the Institut de l’Economie Rurale in Mali and in Ethiopia, FARM-Africa, SOS-Sahel and Awassa College of Agriculture. The problem the research sought to analyse is set out below, followed by a summary of the results and conclusions of the research. Then there is a longer discussion of the three main areas of work. A list of research publications, all of which are available from IDS, is at the end of the report. The problem the research sought to analyse Many people’s lives are a quest to create a secure, sustainable livelihood for themselves and their families. Outside forces, be they natural, political, economic or social all conspire either to make this more or less difficult. This research aimed to find what particular factors enable some people to be successful in their quest when others fail, and what interventions by policy makers might help both groups of people. The research looked particularly at the part played by local, national and international institutions on the building of livelihoods. Researchers wanted to see how institutions could influence the access to benefits like land, money, or employment, of individuals and households. Access to all of these could affect the ability to make a living and achieve security. A major concern of the research programme was to illuminate how poor rural households adapt to changes in entitlements and in institutions, looking particularly at whether they resort to migration, adopt a more diverse livelihood strategy or increase agricultural production through agricultural intensification or extensification. It focused on the policies already in place that would shape the choices made by local people about their livelihoods. Making the right choice could spell the difference between successful, sustainable livelihoods and a household or whole community continuing in, or returning to poverty and environmental degradation. An aim of the research programme, therefore, was to identify new policies that would enhance the ability of people to construct sustainable livelihoods. The programme had a subsidiary aim to show how it would be possible to modify already-existing policies, especially those adopted to further macro-economic reform (structural adjustment programmes, for instance) – to assist this process. 1 Summary of results and conclusions · The research framework identified three strategies pursued by rural people in furtherance of achieving a more sustainable livelihood: migration, livelihood diversification and agricultural intensification/extensification. One of the conclusions drawn is that they are all linked and there are trade-offs that must be made between them in order to achieve the sustainable livelihoods goal. None can be viewed in isolation. · The research has confirmed the usefulness of adopting a livelihoods framework to understand the way rural households cope in poor areas. Livelihood diversification · The existence of local opportunities and levels of population density seem to influence possibilities for diversification as much as factors like levels of rainfall, geographical location and transport links (see below) · Poorer families tend to diversify activities in order to survive a crisis, as opposed to richer families which diversify to accumulate assets · There is likely to be more diversification activity taking place in higher potential, higher density farming areas, where the local economy provides a higher level and broader range of options, than in more marginal areas with low yields, lower population density and a poor range of local opportunities. In Mali, however, the results were not clear cut. In Dalonguebougou, for instance, there was a wide range of diversification activities, despite the area receiving less rainfall and being risk prone. A number of groups had migrated to the village and part of their diversification activities, thus creating opportunities for trading and shop-keeping for local families · The number of available workers in a household will have an impact on the potential for diversification, but the quality of labour management will also play a crucial role in the success of diversification strategies · The key policy options stemming from the diversification work are set out below in Box 1. However, there are limits to what can be achieved through policy interventions aimed at reducing rural poverty in Ethiopia and Mali, given current constraints on governments caused by economic structural adjustment programmes as well as long histories of poor citizen-state relations. 2 Bo x 1 Key pol icy cons id er ation s (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f) (g) Recognise the importance of diverse, dynamic and multi-dimensional livelihood strategies Improve access to credit Support existing mechanisms for migration to enhance positive benefits Strengthen collective rights over natural resources Assess the benefits and costs of infrastructural development Pay attention to livestock Understand social institutions and networks, including domestic organisation (h) Factor-in chance events Agricultural intensification · Different pathways of agricultural change – capital- or labour-led intensification or extensification - can exist side by side within a site and a household may follow more than one path concurrently on different parts of their land · The effects of agricultural intensification may be positive or negative: for example, intensification may have a positive effect on production, but negative effects on environmental sustainability and equality · A household’s decision on which path to follow will depend on a range of factors, central to which are the resources available to them, the institutions which mediate access to resources, the historical background, and the policy context · Capital-led intensification is more easily influenced by policy than labour-led intensification providing institutional linkages, like agricultural inputs and credit supply, are in place. In Mali, for instance the institutional linkages that provide inputs and credit only cover the ‘high potential’ area of the country, so in the ‘low potential’ areas capital-led intensification is not more easily influenced by policy · If the flexibility of a household to make its own choices about which path to agricultural intensification to follow is reduced, then the chances of farmers making the best choice in the light of the available resources, the institutional arrangements and an assessment of risk are also reduced · The research had policy implications in three areas: - livestock disease: unless this problem is addressed, it is unlikely that any policies to combat poverty and improve livelihoods will succeed - flexible extension policies and credit: greater need for flexibility in capitalled intensification packages but also need for policies that do not damage opportunities for the labour-led path, where this is the only path possible to 3 - follow for a household. A functioning and flexible credit market is essential institutions: policies to support successful and sustainable intensification of agriculture must take into account that not all institutions can be influenced directly. The institutions that are the hardest to reach, may be very effective in facilitating the following of certain paths to intensification · The interaction between these complex local (and often informal) institutions and more formal institutional arrangements for natural resource management, in the context of community-based natural resource management on the one hand and decentralised state-led programmes on the other, is a key area for future research Migration · Migration plays a central role in the livelihoods of rural households and communities, rich and poor. Policies should, therefore, be more sensitive to the existence of regular population movement · Different household structures and gender influence who migrates and who decides about migration and the use of remittances; migration is not strongly correlated with poverty, assets or education, although types of migration are likely to be · Policies should take account of the possibility that migration increases inequality. Migration is embedded in social relations which has disadvantages for some household and community members but creates opportunities for supportive policies like the provision of information about migration opportunities, facilitation of remittances and enhancement of the productive impact of remittances The intellectual approach The concept of ‘sustainable rural livelihoods’ is important in the debate about rural development, poverty reduction and environmental management. There were parts of the approach, however, that the project researchers felt should be clarified in order that the ultimate aim of the research programme might be achieved. A particular issue was how it could be decided when someone had built a sustainable livelihood for themselves; that is, what livelihood resources, institutional processes and strategies influenced success or failure for different groups of people and what were the practical, operational and policy implications of adopting the approach itself. To this end, a framework for analysing the approach, and therefore clarifying the above, was constructed (see Figure 1 below). It had at its heart one key question: 4 Given a particular context, what combination of livelihood resources results in the ability to follow what combination of livelihood strategies with what outcomes? Cutting across this was the recognition that certain institutional processes would influence the ability of a household or community to carry out a particular strategy and achieve an outcome. The framework could be applied at many levels: to an individual or household, at village and district, region and national level. It was important to specify the level of analysis and to analyse any interaction between levels, acknowledging the associated positive or negative effect on livelihoods. Figure 1 The sustainable livelihoods framework1 CONTEXTS LIVELIHOOD RESOURCES INSTITUTIONAL PROCESSES LIVELIHOOD STRATEGIES SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOOD OUTCOMES Livelihood Policies 'Natural capital' History 'Economic/ financial capital' Agricultural intensification extensification Institutions and Politics 'Human capital' Organisations Livelihood diversification Agro-ecology 'Social capital' Differentiated social actors Contextual and policy analysis Migration and others . . . Analysis of building blocks: trade-offs, combinations, sequences 1. Increased numbers of working days created 2. Poverty reduced 3. Well-being and capabilities improved Sustainability 4. Livelihood adaptation, vulnerability and resilience enhanced 5. Natural resource base sustainability ensured Analysis of institutional influences on access to building blocks and composition of strategy portfolio Analysis of strategies adopted and trade-offs Analysis of outcomes and tradeoffs What is a sustainable livelihood? The starting point for answering the key question of the analytical framework was to get a precise answer to the other question: what is a sustainable livelihood? 1 This is the original framework set out by Scoones (1998) and used to guide the research carried out by the IDS Sustainable Livelihoods Programme. Modified versions have been produced by (among others) Carney 1998; Neefjes 1999; Toufique 1999; Goldman 2000 and Nicol 2000, but these have generally involved changes of emphasis or terminology rather than removal or replacement of the basic elements of the framework. 5 Only by settling this could desirable outcomes be identified. The IDS research team took as its definition the following: A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (both material and social resources) and activities required for a means of living. A livelihood is sustainable when it can cope with and recover from stresses and shocks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, while not undermining the natural resource base.2 While this definition could, in fact, be interpreted to give at least five ways of assessing outcomes (depending on whether the focus was on livelihoods or sustainability) it illustrated that the concept of sustainable livelihoods was a composite of many ideas and interests. Ian Scoones in his paper Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis (Working Paper 72, 1998, IDS) stated that the important thing to recognise was that the priorities were always subject to negotiation, with some being more important than others at certain times. Making the policy choices to achieve the most beneficial outcomes could be a process of negotiation, enabling the right choices to be made. Livelihood resources The analytical framework described by Scoones in his paper adopted an economics metaphor to describe the basic material and social, intangible and tangible assets that people have in their possession. These resources were the ‘capital’ base from which livelihoods could be constructed. He offered a simple set of definitions: Natural capital – natural resource stocks (soil, water, air, genetic resources etc) and environmental services (hydrological cycle, pollution sinks etc) from which resource flows and services useful for livelihoods are derived Economic or financial capital, including infrastructure – the capital base (cash, credit/debit, savings etc), infrastructure, and other economic assets which are essential for the pursuit of any livelihood strategy Human capital – skills, knowledge, ability to work and good health important for the successful pursuit of livelihood strategies Social capital – the social resources (networks, social relations, associations etc) upon which people draw when pursuing different strategies Whilst more ‘capital’ sources could be identified, the main point was that in order to construct livelihoods, people should successfully combine all or some of these ‘capital’ endowments. Identifying what combinations of capital or livelihoods resources are required for different livelihoods strategies was a key part, then, of this programme’s This definition drew upon the work of Chambers and Conway (1992) and Swift (1989) among others. 2 6 analytical process. As mentioned already, it focused on three particular strategies: agricultural intensification/extensification, livelihood diversification and migration. These were considered to be the realistic choices open to people in rural areas. Understanding, in the context of people’s lives, how different livelihood resources are combined in the pursuit of different livelihood strategies was, therefore, critical to the research. The idea of a livelihood portfolio The combination of activities that were followed in carrying out a strategy were termed the ‘livelihood portfolio’. These activities could be carried out at different levels: as an individual, a household and at village level, as well as at regional or national level. Each portfolio would be different, containing a range of activities, carried out at a variety of levels in response to the resources available and socioeconomic conditions – gender, age, and income levels for instance - prevailing. Over time, indeed over generations, the portfolio of activities might change as local and external conditions changed. It was important, therefore, that the research programme included in its analysis the dynamic nature of livelihood strategies. In fact, whether livelihood portfolio combinations resulted in positive or negative change in relation to the range of sustainable livelihood outcome indicators was a key issue. Both the number of sustainable livelihoods created and their quality could be increased or improved in an area if livelihood resources were combined creatively. Scoones (1998) gives the example of degraded land being transformed with the investment of labour and skill, resulting in the accumulation of natural capital and an increase in the potential for more livelihood opportunities. But a course of action taken by an individual or a household might have negative as well as positive effects, therefore it was vital to look at the net impact of adopting a particular livelihood strategy on a wider group, over time. The research examined livelihood strategy choices over a wide range of natural environments: from areas with low endowment of natural resources to areas where endowment was high. With an accompanying variance in the level of risk experienced by resource users, there was a variety of livelihood strategies followed, and a need for different policy responses in each situation. The influence of institutions and organisations Returning to the key question of the analytical framework, it was recognised by the researchers, that aside from looking at the livelihood strategies adopted in response to the availability of resources, and the success or failure of the strategies measured in terms of their outcomes, it was necessary to look at the influence of external institutions, organisations and processes on the whole process of achieving a sustainable livelihood. Scoones (1998) stated that whilst it was important, exploring only the quantitative relationships between measurable variables - for example, the relationships between economic assets, indicators of agricultural intensification and poverty levels - would result in a limited understanding of the process. For this reason, the analytical framework emphasised the study of institutions and organisations as well. 7 Institutions were seen as dynamic and both formal and informal. They could operate at different levels and wield varying power. An institution might range from a piece of local land legislation to a social custom that blocked women from undertaking certain tasks. But they could, at any time, act as barriers to the success of certain livelihood strategies, or have the potential to improve access of a particular social group to particular resources and so it was important to understand their influence. Operational implications of the framework approach to analysis of sustainable livelihoods Whilst adopting the framework approach was designed to assist the research process, it was also recognised that to investigate each element contained in the key question represented a major research undertaking. It was hoped that at the very least, the framework would supply a ‘checklist of questions’ for the researchers and a starting point for determining the issues to explore. The research methodologies varied according to the element being investigated and were often used in combination to form a ‘hybrid’ approach. The framework also suggested multiple entry points – opportunities - for policy intervention, both conventional interventions (skill and technology transfers etc) and unconventional, in relation to getting the institutional and organisational setting right. It was hoped that an unconventional approach would extend the range of livelihood strategy options and support the conventional interventions to improve their effectiveness. Planning for and implementing a sustainable livelihoods approach needs to be iterative and dynamic. It requires the active participation of everyone involved in the process of defining meanings and objectives, analysing links and trade-offs and identifying options and choices. This was not always possible to achieve in this research process. But the analytical framework adopted by the programme was designed to help in the process, pointing towards areas where actions might proceed and common goals could be achieved. The settings of the research The research sites were chosen to represent a range of higher and lower resource endowment areas. Research in Mali was carried out in two villages, Zaradougou and Dalonguebougou, chosen to reflect major differences in ecological and economic conditions. Zaradougou is in the relatively well-off Sudan-Sahelian zone of southern Mali, dominated by the cotton economy. The household economy is based on cotton, cereals and livestock, although migration to Ivory Coast is a common diversification strategy. Some extended, multigenerational households remain, but many of these have fragmented into smaller, nuclear units. In contrast, Dalonguebougou is situated in a dry and isolated part of the southern Sahel. In this semi-arid zone, the village’s sandy soil is valued for agriculture, making it a popular choice for incomers seeking to establish themselves as 8 farmers. Despite this, population density is no more than 25 per square kilometre. The region has a history of both sedentary farming and nomadic herding with loose boundaries between the two livelihoods. Farming and grazing remain the principle land uses. Three distinct ethnic groups live in the area; across all three groups, however, the extended, patrilineal household remains the dominant structure for managing local livelihoods. The sites in Ethiopia were chosen to represent some of the major differences in population density, rainfall and household activities found within the southern part of the country. Admencho lies in the densely settled southern highlands where fertile soils have allowed the evolution of a farm economy based on intensive land use through the cultivation of enset and root crops. Mundena is in the lower lying plains below the Wolayta plateau. Soils are less fertile than in the highlands, population density lower, temperatures higher. The area was opened up for agriculture 30 years ago and now the farming system is based mainly on cotton and maize, in association with livestock. Access to markets is reasonably good because of a new road linking the village with surrounding settlements. Chokare lies in the lowlands, next to Lake Abaya, and has a much lower level of rainfall than the other two sites. The soils are relatively fertile and irrigation is possible and livestock production. The research area included the State Farm which provides employment for almost nine hundred families. Cultivation of cotton and maize is mechanised, there is a local cash economy with active flows of livestock, agricultural products and services within the economy. Outside the State Farm, people are agro-pastoralists, combining agriculture with livestock. Research methods There were two research teams, basing their work on the analytical framework already described. Researchers were from different disciplinary backgrounds and the final decisions on research methodology made by each team reflected the specific contexts of the research areas as well as the areas of expertise of the researchers. Qualitative methods, including rapid rural appraisals (RRAs) and common field observations, and quantitative methods were used. Earlier research by Toulmin (1992) provided historical depth to the research in Mali. The migration research adopted different emphases for each research site. In Ethiopia, the definition taken of migration was wide. A migrant was defined as a person who had ever lived or worked outside their village. Despite this, only one quarter of households in a survey had a migrant, and the contribution of migration to livelihoods was more limited than in Mali. Quantitative information on migration in Ethiopia was based on a household survey of 300 households across the different site, the survey was preceded by a Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) and followed up by detailed case studies. 9 In Mali, participatory sustainability ranking brought out the importance of household structure and management for livelihoods. Research was carried out by two people using a variety of techniques and building on the earlier research by Toulmin (1992) and Brock and Coulibaly (1999). The research on diversification of livelihoods used a ranking exercise to develop criteria relating to what characteristics are associated with greater or lesser sustainability of a household. The ranking exercise was then used as a basis to test whether livelihood diversification was used as a desperate measure in difficult circumstances or as a means to accumulate assets. 10 Table 1: Characteristics of research sites Country Site Zone and base livelihood Household forms Ethnicity Agricultural intensification Diversification Main forms of labour migration Who migrates? Institutions Ethiopia (Wolayta) Admencho Highland. Root crop/enset, sedentary livestock. Homogenous, but clan system. Long tradition of circular seasonal labour migration (rural-rural and rural-urban). Mainly men. Women as urban domestic workers. Households (nuclear). Agents. Regionalisation. Lowland settlement. Dryland agriculture, formerly much supported. Lowland: state farm (SF), Peasant Association. Dryland agriculture, sedentary and transhumant. Sahelian dryland. Risk prone. Millet, sedentary and transhumant livestock. Capital-led (Global Package of high yielding seeds, chemical fertilisers and credit promoted). Capital-led (Global Package). Loss of livestock. High diversification (trade, labour), more among rich. Mundena Small nuclear household. Femaleheaded household may suffer from male absence. As above. Individual / family. Regionalisation. Wolayta and Sidama (pastoral). Little agricultural extension. Irrigation. Loss of livestock. Relatively little outmigration. Some return place origin. SF: in-migration. Non-SF: declining transhumance. Labour migration. Usually young unmarried men. As above. Medium diversification (trade), more among poorer. SF: agriculture, etc., associated with decline wages. Non-SF: fishing, trade (loss livestock). Families. Men. Men and women. Agents. Households. Regionalisation. Large extended households. One female-headed household. Four distinct social groups. No extension.. Oxen ploughs and livestock are important. Little marketing opportunity. Seasonal circular migration: rural, urban, Ivory Coast. Permanent out-migration. Extended family. Marriage system. Regional agreements, Ivory Coast policies. Large extended households, but practice in decline. Homogenous, two immigrant household. Capital-led (CMDT). Plantations in Ivory Coast. Sales and services in Sikasso. Ownership of cocoa/coffee plantations/farms in Ivory Coast Bambara ethnic group. Men and women migrate, in different systems Mainly men., but also families for long term settlement on cocoa plantation Chokare Mali Dalonguebougou Zaradougou Sudano-sahelian cotton zone. Cash crop. Cotton, cereals, sedentary livestock. Homogenous. Extended family. Regional agreements, Ivory Coast policies. Notes: the columns on agricultural intensification and diversification present comparisons within countries between the sites, not across countries. Definitions are discussed in the country reports. 11 How do poor rural households construct a sustainable livelihood? Economic diversification The detailed look at diversification activities was an attempt to see how poor rural households worked, and to counter the view that they were purely agriculture-based. As a result, it was hoped that policy makers could be encouraged to look, if necessary, at policies outside the agriculture sphere that might be more effective in assisting the households concerned. As Toulmin et al said in their report (Diversification of Livelihoods: evidence from Mali and Ethiopia, Toulmin et al, Research Report 47, 2000, IDS), ‘If equity and gender issues are of particular importance, may diversification provide a more effective pathway to improving livelihoods than reliance on raising crop yields alone?’ Indeed, they questioned whether a poor household would ever be able to generate enough assets and labour to run a farm and whether it would be better for them to focus their efforts on a specific niche activity such as trade, market gardening or firewood collection. The many contextual factors that might influence the choice of livelihood diversification strategy have been examined on several occasions. In Factors influencing the dynamics of livelihood diversification and rural non-farm employment in space and time (Jeremy Swift, 1998, IDS), Swift points out that high population density, good road networks and incoming migrants might all increase the potential for economic diversification, but that the range of off-farm activities that were actually employed depended, in the end, as much on factors like access to credit and savings, household size and composition, levels of education and in some places, on cultural constraints. Ellis in Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in developing countries (2000, OUP) adds geographical location, household characteristics, market opportunities, the relationship between farm and off-farm activities and the influence of formal and informal institutions as factors that will influence the choice of livelihood diversification strategy undertaken. The research carried out in Ethiopia and Mali identified the contextual factors influencing diversification choices and analysed what impact the diversification of activity had on household income, well-being and sustainability. The researchers sought the answer to the question of whether livelihood diversification by individuals leads to households breaking up, or provides the space that individuals seek while contributing to a more cohesive domestic group or household. The results from the two countries were compared. Bangladesh was not included because the methods and approach followed by the country research team generated results which could not be compared with the other two countries. Geographical location In Mali, most farmers had attempted to spread the effects associated with being in a high-risk area by developing non-farm activities. In the case of Dalonguebougou – situated in a low rainfall, high risk area - these were trading and shop-keeping, hiring themselves out as agricultural wage labourers, cotton weaving and spinning, small stock rearing, granary making, migration and fortune telling. In Dalonguebougou, there had been a significant amount of in-migration by herders from other areas who, finding livestock rearing alone no longer provided them with a 12 livelihood, perceived the village as having potential for settling and starting to farm. Whilst this process of settlement reduced the amount of available cultivable land for the traditional inhabitants of the village, it had also increased local opportunities for trading and shop-keeping (the comparison of items for sale in Babou Dembele’s shop, see Box 2 below, makes clear how much the activity has grown). As such, there had been a trade-off between the livelihood diversification of some groups and agricultural development of others. Box 2 Di ve r si fi cat ion in t rad e: Wh at c an I bu y in B a bou De mb el e’ s s hop ? A c omp a ri son of 1 9 80 and 19 9 8 1980 Green tea, sugar, soap, cigarettes (Liberté brand only), salt, kerosene, sweets, kola nut, dates 1998 Green tea, brown tea, sugar, soap, cigarettes (many brands), salt, kerosene, sweets, kola nuts, dates, nail varnish, biscuits (3 types), scissors, honey, children’s toys, rope (plastic), rope (baobab bark), string, razor blades, oil lamps, milk powder, condensed milk, soap powder, bicycle parts, spare parts for mobylette, tyres, clothes, buckets, plastic pots, metal cooking pots, knives, tomato paste, bicycle pumps, local cloth, factory made cloth, batteries (4 kinds), plastic sandals, instant coffee, matches, orange drink (powdered in a sachet)... In Ethiopia, there was no clear difference in levels and patterns of diversification between the higher rainfall area of Admencho and lower rainfall Chokare. In Mundena, which fell in between the two in rainfall terms, there appeared to be a wider range of diversification activities. It seemed therefore, that there wasn’t a particular connection with climate, but more with the opportunities available locally. A road had recently been built close to Mundena, creating new marketing opportunities. In Chokare, the employees of the State Farm provided a captive market for local small businesses to develop. The researchers did find a link between population density and diversification, with non-farm activities like trading and shop-keeping being more evident in higher density areas like Admencho. Who diversifies – the rich or the poor? The researchers assumed that the purposes and outcomes of livelihood diversification would differ between households according to their social and economic status (Toulmin et al, 2000). Poor households would diversify in order to survive; richer households would do it in order to accumulate. Poorer families could never earn enough from diversification of their activities to accumulate assets, whereas people from the richer families, being under less pressure to contribute to the central purse, could pocket the income from their various subsidiary activities themselves. In Mali, in the two case study areas, this assumption seemed to be borne out. However, in Zaradougou, Mali, pursuit of diversification activities could be a source of tension within wealthier families because it increased competition within the household. Whilst the activities themselves might make a family financially better off, well-being and sustainability sometimes decreased, with some families coming close to splitting up. In Dalonguebougou, however, diversification was undertaken by different members of the household at different times, essentially within the structure 13 of the extended multigenerational household. There was a close association between asset ownership and household size and asset ownership with sustainability. Those families with more assets had larger more stable family groups. Likewise there was a direct link between successful crop production and cattle ownership and well holdings. In Ethiopia, different correlations were found between livelihood diversification and wealth rank in the three research sites: for all groups in Admencho, the largest proportion of income came from non-farm sources, whereas in Mundena and Chokare, off-farm income seemed to be more important for poorer groups than for those in the higher weath ranking groups. In all case study sites in the two countries, it was noted that it was the younger members of the household who were encouraged to pursue alternative livelihood strategies. In Zaradougou, Mali, for instance, it was the young men who were sent to establish plantations in Ivory Coast. Similarly, in Ethiopia, it was the younger men who left home, particularly in the Wolayta plateau region where it was not possible to give them land locally on which to set up their homes. But from the limited data collected, it seemed that neither the richer or poorer families were particularly involved in migration. The poorer households because they could not spare any family members but needed them as labour on their own farms, the richer families because there was less need to travel. In Ethiopia, around two thirds of all households had a member who was carrying out a secondary activity as well as the core activities. But, as said above, different correlations were found between wealth and diversification in the three sites. Does livelihood diversification lead to a sapping of the agricultural sector? There was no simple answer to this; a variety of capital and labour flows between agriculture and other household activities evolved over time, having a positive impact on farming in some cases, and negative impact in others. In southern Ethiopia, for example, the highest ranked households had become wealthy by pursuing both trading opportunities and agriculture, the income from trading being invested in intensified farming. Poorer households with little financial capital to invest relied upon other resources, particularly social capital, to be able to intensify their agricultural practices. In Dalonguebougou in Mali, farming was still the most important activity. In most households the demands of farming imposed constraints on diversification activities, even though sending a family member away in the dry season to earn an income could generate much-needed cash. In Zaradougou, the poorer households found it hard to run a productive cotton and cereal farm so diversification – trade-related activities in the nearby market town – actually provided them with an alternative to agriculture. The wealthier families could rely on money and labour flowing between the plantations in Ivory Coast and their farms in Mali. 14 Livelihood diversification and the development of local and wider markets The evidence from both Ethiopia and Mali backed up the argument made by Wiggins (2000) that diversification activities would be greater in areas of high potential, and high density farming because the opportunities would be greater. The high levels of trade in Admencho, Ethiopia were there because of the high population density. In Mundena, the building of a new road increased the potential for livelihood diversification and in Chokare the State Farm provided trading opportunities in food and services for local people. Zaradougou in Mali had the market town of Sikasso nearby which generated opportunities. By contrast, Dalonguebougou was more isolated but the significant flow of people into the area had created a captive market of its own, enabling trade and shop-keeping activities to develop. Are livelihoods becoming more diverse and if so, why? The evidence was mixed on this point. In Mali, whilst the number of incomegenerating activities had increased over the years in the two research sites and people relied more on off-farm activities to satisfy their needs, they still defined themselves as farmers and continued with their agricultural activities. They invested in the expansion and intensification of their farming enterprises and lived in traditional farming households. In Ethiopia, natural disaster – drought - forced people into alternative livelihoods such as the collection and sale of firewood and grasses. Outbreaks of cattle disease forced herders to settle and start cultivating the land in Chokare, and in Mundena, the loss of draft power made farming less viable, forcing poorer households to pursue alternative sources of income. How do household development cycles and livelihood diversification opportunities interact? Interaction depends particularly on the type of household in question. Nuclear families will follow a marked cycle linked to their structure and dependency ratio; at times there will be a high number of young children and a high dependency ratio, then as the children grow up they will become a considerable asset – a valuable source of labour. The household may become weaker as children leave home and become independent. In an extended household this cycle is less marked as there is likely to be a broader spread of ages. In Ethiopia, households tend to be small with a nuclear structure. This structure and immediate kinship networks are central to defining the breadth of choice in developing diversification activities. The large, complex households of Mali are less affected by the development cycle, but nevertheless households will differ in the kind of labour force that they have available at any time. The capacity to mobilise a large, energetic labour force ( particularly of young unmarried men) is a key to the development of diverse activities and assets. It is not enough to guarantee sustainability, however; good management of the labour is crucial to maintain the balance between individual and collective interests and incomes. The role of institutions in determining livelihood diversification opportunities and outcomes Institutional influences could also affect the ability of households to diversify by gaining access to credit, land and so on. These institutions were identified by the project researchers as being both informal and formal, from local councils, 15 government credit schemes and crop marketing bodies to savings clubs and village schemes for sharing plough teams, donkeys or wells. The household remained the primary mechanism for the pooling of incomes, division of labour and the sharing of risks in all sites. Yet, households took on different forms in Ethiopia and Mali; different sizes, structure, rights and responsibilities, status and degrees of individual freedom within the wider domestic group. Evidence from all the sites suggested that the influence of formal and informal institutions will vary over time, as the ‘balance of power’ between them changes. Agricultural intensification What has been highlighted so far is diversification activities that involve moving off the farm, either to build up activities away from agriculture or to supplement farm activities with a secondary form of income. A major part of the work by the project researchers looked at an alternative strategy: staying on the farm and intensifying activity and production. Agriculture remains, for many rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa, the single most important source of income. Increasing outputs from agriculture, in the face of increasing pressure on resources, is a major challenge for all policy makers. The intensification process can be highly complex and policy responses have to reflect this. The research team identified the factors that inhibited or facilitated the process of agricultural change. In the course of doing so, the issues of access to the resources necessary for intensifying activity and the way that richer and poorer households therefore intensified agricultural activity were examined. As Grace Carswell stated in her report (Agricultural intensification in Ethiopia and Mali, Research Report 48, 2000, IDS), it was vital to understand the trade-offs between adopting different livelihood strategies and seeking to gain access to resources in order to understand the dynamics of agricultural change. An alternative to agricultural intensification is extensification, that is, the expansion of an area under cultivation into previously uncultivated areas with no increase in the ration of inputs – labour or capital – to land. In as much as extensification is also a means of increasing agricultural production, it was examined in the research alongside agricultural intensification. The major focus of state policy in Ethiopia and Mali is the promotion of capital-led paths of agricultural intensification, that is, intensification which entails substantial use of capital, be it artificial inputs like fertiliser and high-yield seeds or access to credit. (Labour-led intensification involves the use of more labour and effort and is a strategy intended to save capital.) This has been achieved in a range of ways across the sites: through extension programmes (new technology and inputs), price policy (subsidies on fertiliser), infrastructure-based services (cotton marketing boards), credit provision and irrigation promotion. Intensification policies in Mali have focused on the cotton and rice industries and agricultural intensification outside these areas has largely been left untouched. 16 These policies of capital-led agricultural intensification help those households and individuals who fall within their remit and are able to follow a capital-led path, but do nothing to help those who cannot. The research, therefore, sought to find out who could follow this path and who had to follow a labour-led model and why, and the institutional arrangements that would facilitate both. In Ethiopia, there was a wide range of formal and informal institutions that facilitated the capital-led path of intensification promoted by the Bureau of Agriculture (for instance, the ‘Global Package’ extension programme promoted particularly by the Sasakawa Global 2000 programme). In Mali, the Compagnie Malienne pour le Dévéloppment des Textiles (CMDT), operated in Zaradougou but not in the milletproducing area of Dalonguebougou. In both Ethiopia and Mali, however, the institutions that facilitated the labour-led path were principally informal. Indeed in Mali, it was the household that emerged as a key mediating institution for decision making about investment in agriculture. Large, multi-generational households were involved in complex decision-making around resource management, including the investment of capital and labour (See Table 2 below). These various institutional arrangements functioned in each research site in a way that enabled the necessary resources to be accessed by different groups in the face of different scarcities. Political and social change led to institutional arrangements changing (for example, land, labour and livestock accessing arrangements in Ethiopia following the Revolution) as did an increase in livestock disease. In fact, whilst some institutions declined in importance under pressure from various factors (hara arrangements for sharing the use of livestock declined in Mundena as disease incidence increased), others took their place (church working parties particularly helped poorer households in these circumstances). The changes in institutional arrangements could be a critical influence on the choice of path followed towards agricultural intensification. But there were additional factors like climate, transport links and macro-economic policies that also had an impact. Where all these factors led to a scarcity in certain types of capital there were tradeoffs made between different paths and different use of capital. For example, an absence of financial capital that would enable a capital-led path of intensification to be followed, might be compensated for by an availability of social capital. Social capital could allow the same path to be followed (by providing, for example, informal credit through a local credit association based upon social capital), or a different labour-led path to be followed (through work groups also based on social capital). The ability to adapt and trade off one path against another would involve varying levels of risks and might require different timescales, with varying impact on the sustainable livelihoods’outcomes. Following a labour-led path of intensification, for instance, might have a beneficial impact on the number of working days created, but an increase in working days might not necessarily lead to long term alleviation of poverty, despite the household working harder. The research looked at the differences between households in agricultural paths followed. Richer and poorer households were compared, female- and male-headed households and different ethnic groups. Then the differences in strategies within a household were examined, often depending on the different plot and crop types. 17 In Ethiopia, the research showed that for poorer households with adequate labour (and without access to capital), capital saving intensification strategies were especially critical for constructing a sustainable livelihood. Labour decisions were made at the household level and there was a high degree of involvement in local social networks to share labour and resources. Female-headed households often had a shortage of male labour – particularly crucial for ploughing – which impacted on both a capitalled and a labour-led intensification path. In this situation, options for achieving a sustainable livelihood were considerably constrained. The greatest flexibility could be achieved in a household with several young males who represented the necessary workforce for a labour-led approach, but could also go off farm to earn money through other non-agricultural activities, bringing back capital to be invested in the farm. A household like this was in the ideal position of being able to follow both strategies towards intensification and diversify its income source. The research site of Dalonguebougou in Mali is home to three different ethnic groups. There was a difference in the agricultural intensification paths followed, in part due to the different traditional livelihood practices of each group and in part due to varying access to resources and institutional involvement. In Ethiopia, within a household, families treat different parts of their farmland in different ways: the area around the house being farmed more with a labour-led strategy, and the part beyond this, a capital-led approach. This more distant farm would be ploughed more and there would be greater use of chemical fertilisers. The gender divisions in labour would require more female workers in the plot near the house (the darkua) and more men to do land preparation,weeding and ploughing in the other area (the shoqa). Consequently, again the make up of the household itself would influence the choice of intensification process which could be followed. There were other explanations for the intensification path followed across the five research sites in Mali and Ethiopia. Different historical traditions and experiences, levels of social capital and institutional arrangements that enabled access to resources; ecological niches and social norms all influenced the decision on which course to follow or which combination of strategies to follow. 18 Table 2 Institutions to access key resources (in addition to those resources already owned by the household) Capitals Resources Admencho, Ethiopia Mundena, Ethiopia Chokare, Ethiopia Zaradougou, Mali Dalonguebougou, Mali Land Sharecropping arrangement (Kotta-land) Sharecropping arrangement (Kotta-land) Sharecropping arrangement (Kotta-land) Dominance of village Bambara in customary land and water tenure. All other groups negotiate access through village Bambara. Water n/a n/a PA, SF Land stays in hh on death of hhh; Women gain access to individual plots through marriage; hh breakup causes division of land holdings; Access for immigrants is negotiated through the village chief (‘customary land tenure’). n/a Inputs BoA (Global); PA; market BoA (Global); PA; market None for fertiliser (illegally through State Farm for seeds). Livestock Inheritance; purchase (whole or part); share ownership (kotta); share rearing (hara); ownership under ‘share-for-profit’ arrangement (tirf yegera); pairing of oxen (gatua); borrowing for free (woosa); in exchange for labour. Inheritance; Purchase (whole or part); share ownership (kotta); share rearing (hara); ownership under “share-for-profit” arrangement (tirf yegera); pairing of oxen (gatua); borrowing for free (woosa); in exchange for labour Inheritance; Purchase (whole or part); share ownership (kotta); share rearing (hara); ownership under ‘share-for-profit’ arrangement (tirf yegera); pairing of oxen (gatua); borrowing for free (woosa); in exchange for labour. Natural Physical Equipment Association Villageois administers credit for inputs, oxen and tractors from CMDT at village level, and provides fertiliser. Ownership of livestock and equipment by individuals and hh; draft power/labour exchange agreements; draft power borrowing agreements; CMDT credit provision for draft oxen; use of hh agricultural equipment for individual or sub-household fields; hire of tractor for cash. Association Villageois administers credit (for inputs) from CMDT (through BNDA and Kafo Jiginw); Loans from Association Villageois under difficult circumstances “Informal contracts” of rights and obligation between a hh and its members; involves payment for some members of hh; Management and distribution of labour between Zdg and plantations in Ivory Coast Economic / financial Credit BoA (Global) Traditional credit and savings groups (iddir, equb) BoA (Global) Traditional credit and savings groups (iddir, equb) SF (SF workers only) Traditional credit and savings groups (iddir, equb) Human Labour skills Management skills Various working groups (hashiya, zayea, dago); begging for labour (woosa); Church group (asrat) Various working groups (hashiya, zayea, dago); begging for labour (woosa); Church group (asrat) Various working groups (hashiya, zayea, dago); begging for labour (woosa); Church group (asrat) Social Social networks Clan, Church, Iddir, PA Clan, Church, Iddir, PA Ethnicity, Clan, Church, Iddir, PA, Age groups SF Dominance of village Bambara in customary land and water tenure. All other groups negotiate access through village Bambara. No credit available, limited inputs on open market. Draft-water exchange; draft borrowing; draft-labour exchange; water-manure exchange. Informal credit available through kinship networks. Family labour; visiting women, harvest workers and hired agric. workers (both paid in millet); ton: age group based work parties; nyo gisi ton: threshing/winnowing work groups; labour-labour exchanges (especially during seasonal bottleneck; hired herders (wage: millet) Ethnicity, marriage paths, age groups, religious groups hhh, head of household PA, Peasant Association SF, State Farm BoA (Global), The Bureau of Agriculture's extension package 19 Migration The aim of this research programme was to inform policy and to ask the key question, ‘What policies could facilitate the contribution of migration to sustainable livelihoods?’. It started from the position that migration as a strategy could have a positive effect on constructing a sustainable livelihood and that policies, instead of trying to limit migration, should support it where it could help poor communities (Migration and livelihoods: case studies in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Mali, Arjan de Haan et al, Research Report 46, 2000, IDS). Much migration research has emphasised the importance of the structure of migration streams, how migrating people use networks and social contacts to help them and how migration movements are determined by the rules of their home society. Migration is not necessarily an unplanned reaction to an environmental shock or economic pressure, but is often a regular practice and considered quite normal. This was certainly backed up by the history of the areas in Ethiopia and Mali in which this research was carried out. The sites in the two countries studied had markedly different migration practices. In Ethiopia, the history of the research district was one of mobility, though how this had impacted on livelihoods had varied. A melting pot of peoples and cultures, it had seen several different political regimes, some of which had severely limited population movement. Perhaps because of this, rates of migration were generally low. In Mali, both research sites had high levels of migration, consistent with the historical context of the West African region but with very different patterns. In Zaradougou, as was seen earlier, there was a regular and accepted migration by part of the family to the coffee and cocoa plantations owned by them in Ivory Coast. Families spread their risks in this way and often had very substantial income to bring back to invest in the farm. This was not a totally risk-free strategy, however, as the process of obtaining a plantation had become increasingly difficult and expensive. In the other Malian site, Dalonguebougou, the pattern of migration varied with the ethnic groups. Migration had long been a feature of the Bambara livelihood system and an important source of income; for the other groups, it was less so. The research looked at the activities and background of people migrating. In Ethiopia, information was not readily available, but education and daily work seemed to be the two most important categories of activity. Migrants from Zaradougou in Mali worked on the plantations in Ivory Coast. Migrants from Dalonguebougou were active in a variety of areas including bricklaying, loading and unloading cargo lorries, welldigging in Ivory Coast and working on irrigated rice and vegetable production near the town of Niono. The activities of these migrants had also changed since the 1980s when young men would spend several months away in weaving jobs at Segou, harvesting rice or digging wells in Ivory Coast. Age and gender were two important factors. Migrants tended to be young and male, but women migrated as well. In Ethiopia, migrants were mainly male and there was relatively more migration of unmarried men in the Ethiopian sites than in Mali. In Dalonguebougou in Mali, women had always migrated for seasonal work in rural areas, but recently they had taken up migration to urban areas (although this didn’t seem to be particularly profitable). 20 In any study of how migration impacts on constructing sustainable livelihoods, it might be expected that there would be high levels of activity amongst people and households with few assets and from poor areas. In the Ethiopian research sites this was clearly the case: migration was predominantly by those who did not have a plot of land or had no animals to support the household. It seems overall, however, that the type of migration and conditions at the destination are crucial factors, muddying the relationship between economic status and migration. There was no doubt that local institutions had a strong influence over patterns of migration. Personal contacts and networks and the role of the family in planning migration were all important. Personal networks played a role in all three research sites in Ethiopia: a young man from Admencho migrated to a nearby town to join his uncle and become a shoe polisher, for example. A surprising find in Ethiopia, however, was that many people did not know where their relatives had gone. Some went away for years and did not keep in touch. Migration was more an individual affair and less determined by the household than in Mali. In Zaradougou, Mali, networks were exceptionally close and in Dalonguebougou, migration patterns were strongly determined by ethnicity. Education appeared to play little role in whether or not people migrated, although the different activities were so diverse that it would be hard to make a significant link. The different forms of household – small nuclear families or vast extended households – however, did influence migration patterns. In Ethiopia, family members proposed that a younger member of the household should migrate, even though in most cases, it was largely the migrant’s savings that subsidised the trip. In Mali, the structure of the household was central to access to migration opportunities. In Zaradougou, large multi-generational households were beginning to breakdown and migration caused tensions at home with the issue of trust being of crucial importance. There was always the possibility that a young man would leave his family and set up on his own. In Dalonguebougou, however, the traditional structure was maintained. Whilst migration allowed the younger male members more freedom away from quite a controlled labour management system, in Dalonguebougou the incidence of young men ‘setting up on their own’ was virtually nil. It was more likely that in families where labour and men were short, the household head would not allow the young man to leave anyway. Young women migrate too and this was seen particularly in Mali among the Bambara in Dalonguebougou. The main motivation to earn money was to raise enough for the bridal trousseau and it was the mothers who decided when their daughter should first start to migrate. The movement was based on kinship networks and was linked in with the whole complex institution of marriage. Only women in the poorest households used any of their migration earnings to make a direct contribution to the central household pot, otherwise it was considered to be an important contribution towards a family’s marriage obligations. Whilst most female migration was within rural areas, there was urban migration, with many women becoming domestic servants. Migration was a central part of the livelihoods of households and individuals in several of the research sites. It was strongly embedded in local institutions and seen as socially and culturally ‘the norm’. Migration contributed to reducing the vulnerability 21 of households, and had a positive effect on incomes and social relations. On the negative side, it could lead to a lack of labour for certain key agricultural tasks and therefore reduced rural production. The research did not produce comparable quantitative estimates of the impact of migration on livelihoods. In fact, one of the lessons learned was that it was difficult to generalise about this. In policy terms, particularly, it was seen to be important to be aware of specific contexts in order that policies could be as supportive as possible. They needed to take account of the possibility that migration could increase inequality, that it was an activity embedded in social relations and that this could have disadvantages for some people. At the same time, it could create opportunities for supportive policy making. How does policy influence livelihood strategies and can poor people influence the policy process? In Analysing policy for sustainable livelihoods (Alex Shankland, Research Report 49, September 2000, IDS) a key strength of the sustainable livelihoods approach is held to be its potential for ‘linking the micro to the macro’, that is for linking what is actually happening at village level with the higher levels at which policies intended to make changes are formulated. Shankland (2000) identifies some specific limitations to the framework approach as a tool for policy analysis and outlines strategies to address these. A model of how policy affects livelihoods One strategy is to draw up a model of how policy affects livelihoods. Policy analysis should be linked with sustainable livelihoods analysis so that the connection can be made between the macro- and the micro-level. If the role of certain institutions and organisations in implementing policy can be identified, through policy analysis, it can then be seen through sustainable livelihoods analysis whether those same institutions and organisations are present within a local community and how much local people interact with or influence them. Policies that can change, reinforce or reduce the supporting or constraining role played by these existing institutions and organisations will be the most effective for supporting the construction of sustainable livelihoods. The research shows that people are not merely passive victims of ‘bad’ policy or beneficiaries of ‘good’ policy, rather that they may not always have the leeway to adapt livelihood strategies to respond to new or different policies. In this situation, the response may be merely a negative coping strategy. It is within this whole context that Shankland (2000) formulates a model, consistent with the analytical framework, of how policy affected livelihoods, summarising it as: Policy operates through specific institutions and organisations to influence people’s choice of livelihood strategies, by changing their perception of the opportunities and constraints which they face in pursuing different strategies, and the returns which they can expect from them. This can be presented visually using the diagram in Figure 2 below. The diagram illustrates the range of elements that should be taken into account in a policy analysis 22 and the complexity of some of the linkages between them. It also highlights the overlap with the aspects of policy analysis that might also be dealt with in a sustainable livelihoods analysis. Figure 2 Links between people-centred & policy-centred analysis3 Policy Process and actors How policy is made, and who influences the Social Capital Peoples capacity to articulate demand or influence the policy process. Livelihood Priorities Priorities of the poor and the policies shaping them process. Policy Context Political, social and economic envrionment. Institutions and organisations The interface between policy and people. Livelihood Strategies How policy impacts on peoples livelihoods. Sustainable Livelihoods Analysis (people centred) Policy Measures Programmes, regulations, laws, etc. for implementation of policy. Policy Statement Written or formal statement of policy intent sanctioned by government. Policy Analysis for SL (policy centred) Can poor people influence policy? Secondly, analysing the vertical dimension of social capital and determining which groups of people are aware of their rights and in a position to make claims on the state should be combined with an examination of the opportunities for direct participation by the poor in defining policy priorities and holding to account those who are responsible for implementation. Citizens might seek out as allies alternative structures like NGOs or church groups to increase their opportunity, especially where there is a high degree of rights awareness on the part of the community but little capacity in state structures to respond. NGO or church groups may represent too the groups that have little awareness or which lack organisation. In communities where there is a high level of inequality, with a local governing elite and marginalised groups, the marginalised people may find that the NGOs or state structures independent of the local elite may be in a position to help them. If these relationships could be developed to increase the vertical social capital of a poorer groups, the chances of poor people having a greater say in the policy making that had an impact on their attempts to build a sustainable livelihood would also increase. In Mali, for instance, the establishment of newly-elected decentralised structures (communes rurales) may provide an opening for greater debate and negotiation of local policy by local people. Shankland pointed out, however, that where the aim of research is to identify entry points for influencing policy processes there should be a distinction made between situations where poor people have a voice themselves to do this and where in fact, their voice is controlled by other institutions. 3 This diagram is taken from Tools for Sustainable Livelihoods Policy Analysis, Katherine Pasteur, 2001 (forthcoming on www.livelihoods.org)) 23 Pursuing a policy-centred approach From this discussion around the interaction of policies and livelihoods and the links between people and policies, Shankland (2000) drew up a five stage process for moving from an initial identification of who were the poor people striving to construct a sustainable livelihood to how they might be helped to find entry points for influencing the policy process more effectively themselves (see Box 3 below). Box 3 Analysing policy for sustainable livelihoods: a checklist Part 1: Livelihood priorities 1 Who and where are the poor? 2 What are their livelihood priorities? 3 What policy sectors are relevant to these priorities? Part 2: The Policy context 1 What is policy in those sectors? 2 Who makes policy in those sectors? 3 What is the macro policy context? Part 3: Policy measures 4 What measures have been put in place to implement each policy? 5 What are the characteristics of these policy measures? 6 Through what institutions and organisations are these measures channelled? Part 4: Policy in the local context 7 In what shape do these institutions and organisations exist locally? 8 What other institutions and organisations affect local responses to policy? 9 What other local institutions and organisations might policy affect? Part 5: People and policy 10 What resources can poor people draw on to influence policy? 11 What opportunities exist for poor people to influence policy directly? 12 What opportunities exist for poor people to influence policy indirectly? 24 Annex 1 Research Reports from the Sustainable Livelihoods Research Programme Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis IDS Working paper 72 Ian Scoones 1998 22pp 1 85864 224 8 Sustainable Rural Livelihoods in Mali IDS Research Report 35 Karen Brock and N’golo Coulibaly 1999 162pp 1 85864 269 8 Sustainable Livelihoods in Southern Ethiopia IDS Research Report 44 Grace Carswell, Ajan de Haan, Data Dea, Alemayehu Konde, Alex Shankland and Annette Sinclair 1999 278pp 1 85864 311 2 Migration and Livelihoods: case studies in Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Mali IDS Research Report 46 Arjan de Haan with Karen Brock, Grace Carswell, N’golo Coulibaly, Haileyesus Seba and Kazi Ali Toufique 2000 36pp 1 85864 320 1 Diversification of Livelihoods: evidence from Mali and Ethiopia IDS Research Report 47 Camilla Toulmin, Rebeca Leonard, Karen Brock, N’golo Coulibaly, Grace Carswell and Data Dea 2000 59pp 1 85864 324 4 Agricultural Intensification in Ethiopia and Mali IDS Research Report 48 Grace Carswell 2000 46pp 1 85864 325 2 25 Analysing Policy for Sustainable Livelihoods IDS Research Report 49 Alex Shankland 2000 42pp 1 85864 326 0 For a summary of the Mali work see a working paper from the IIED Drylands programme entitled Sustainability Amidst Diversity: Options for Rural Households in Mali www.iied.org/drylands/research.html#poverty For details of the next phase of the sustainable livelihoods research programme, focusing on southern Africa, please refer to the Environment Team pages of the IDS website at: www.ids.ac.uk/ids/env 26 Annex 2 Livelihoods Connect – www.livelihoods.org Livelihoods Connect is a website that has been up and running since the beginning of 2000. Aimed primarily at DFID sustainable livelihoods advisers, it also has a wider appeal for anyone working in this area. It is extremely practical and provides learning tools for following the sustainable livelihoods approach, a database of relevant documents and distance learning materials. The site is regularly updated. Three other key sections to look at are: Sustainable Livelihoods Resource Group – Network page http://www.livelihoods.org/resourceGroup/ResourceGroup_network.html This section showcases the capabilities and work of the sustainable livelihoods resource group member institutions, highlighting opportunities for collaboration and indicating how to get in touch. Organisations links and events http://www.livelihoods.org/info/info_linksEvents.html Here is the guide to the links worth accessing on the websites of the sustainable livelihoods practitioner organisations and a list of events and latest developments in the area. The Post-it Board http://www.livelihoods.org/post/postItBoard.html This section gives anyone the opportunity to share their knowledge and insights, experience and views on the sustainable livelihoods approach. Details of a project under development entitled Transforming bureaucracies and understanding policy processes for sustainable livelihoods (James Keeley, Kath Pasteur and Ian Scoones: Institute of Development Studies, Sussex) can be found on the Post it board and comments on the research plan are invited. 27 Annex 3 Other references Carney, D., 1998, Implementing the sustainable rural livelihoods approach. Paper presented to the DfID Natural Resource Advisers’ Conference, London: Department for International Development Chambers, R., and Conway, G., 1992 Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st Century, IDS Discussion Paper no 296, Brighton, IDS Ellis, F., 2000, Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries, Oxford: Oxford University Press Goldman, I., 2000, Micro to macro: policies and institutions for empowering the rural poor, report for DfID (available through www.livelihoods.org) Greeley, M., 1999, Poverty and well-being in rural Bangladesh: impact of economic growth and rural development, Main Research Report produced for ESCOR, Brighton: IDS Neefjes, K., 1999, Oxfam GB and sustainable livelihoods: lessons from learning, paper presented at IDS Sustainable Livelihoods Programme Workshop, Brighton, June 1999 Nicol, A., 2000, Adopting a sustainable livelihoods approach to water projects: implications for policy and practice, ODI Working Paper no 133, London: Overseas Development Institute Swift, J., 1989, Why are rural people vulnerable to famine?, IDS Bulletin, vol 20, no2 Toufique, K., 1999, Sustainable livelihoods in Bangladesh, mimeo, IDS Sustainable Livelihoods Programme Research Report, Brighton: IDS Toulmin, C., 1992, Cattle, women and wells. Managing household survival in the Sahel, Oxford: Clarendon Press 28