Materials and Methods Participants As described previously (McKay

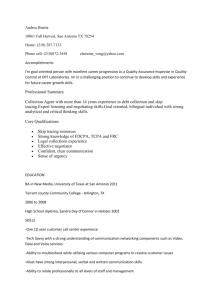

advertisement

Materials and Methods Participants As described previously (McKay et al, 2013; Olvera et al, 2011), GOBS study subjects were recruited from two studies: The San Antonio Family Heart Study (Mahaney et al, 1995; Mitchell et al, 1996) and the San Antonio Family Gallbladder Study (Puppala et al, 2006). Family members of individuals who participated in these studies were also recruited. Initially (1992 – 1995), the San Antonio Family Heart Study included 1431 Mexican-American individuals from 42 extended families. Probands were identified from the Hispanic community in three phases. First, a census tract comprising a low-income neighborhood of South San Antonio was selected. Although San Antonio is 61% Hispanic, residents of these neighborhoods were of 81% Hispanic ancestry (www.census.gov). Second, all residential addresses within these neighborhoods were identified in the telephone directory. Third, households were approached in random order to determine whether any resident met established proband eligibility criteria. A proband had to be Mexican-American, 40 – 60 years old, have a spouse willing to participate, and have at least six offspring and/or siblings older than 16 years residing in the San Antonio area. Once a proband was enrolled, all first-, second-, and third-degree relatives of the proband and of the proband’s spouse, who were at least 16 years old, were invited to participate. Mexican-American spouses of these relatives were also invited to participate. Recruitment procedures were similar in the San Antonio Family Gallbladder Study (1998 – 2001), which included 740 individuals from 39 MexicanAmerican pedigrees (Duggirala et al, 1999; Puppala et al, 2006). However, probands in the Gallbladder study were required to have type-2 diabetes and only unilineal relative recruitment was conducted. As type-2 diabetes has a lifetime prevalence approaching 30% in this population, single ascertainment for such a common disease represents effectively random sampling. The GOBS study recruited individuals from these two cohorts, and children and grandchildren of probands who are now older than 16 years of age were also invited to participate. Sixty-two percent of the GOBS sample is from the San Antonio Family Heart study, 26% from the San Antonio Family Gallbladder study, and 12% are children or grandchildren of San Antonio Family Heart study participants. Over 80% of all individuals contacted agreed to participate in the GOBS study. Thus, participants were pseudo-randomly selected from the community, with the constraints that they must be of Mexican-American ancestry and part of a large family from the San Antonio region. Stated pedigree relationships were verified using PREST (McPeek and Sun, 2000) on available autosomal markers. 872 Mexican-American individuals from the GOBS study are included in the current analyses. Participants were 64% female, ranging in age from 18 – 85 years old (43.66 years, SD 14.9). Exclusion criteria for the study were history of neurological disorders and MRI contraindications. Reported pedigree relationships were confirmed with autosomal markers. All participants provided written informed consent, approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and Yale University. Results Co-morbidities. As can be seen in Table 1, individuals with a lifetime history of AUD were more likely to have had lifetime nicotine dependence (χ2=90.16, df=1, p=2.19x10), a history of substance use disorders (χ2=92.64, df=1, p=6.26x10-22), or a mood 21 disorder (χ2=27.64, df=1, p=1.46x10-7) compared to individuals without AUD raising the possibility that these traits could confound the results presented above. Similarly, the maximum number of alcoholic beverages consumed in a 24-hour period was significantly higher for individuals with a lifetime AUD compared to those without (χ2=257.78, df=1, p=5.2x10-58). However, none of these traits significantly influenced amygdala volume: lifetime nicotine dependence (p=0.268); lifetime substance use disorder (p=0.899); lifetime mood disorders (p=0.855); or maximum drinks in a 24-hour period (p=0.199). Similarly, lifetime nicotine dependence (p=0.266) and history of lifetime mood disorders (p=0.953) were not statistically associated with inferior lateral ventricle size. Yet, history of a lifetime substance use disorder (χ2=7.81, df=1, p=0.005) and the maximum drinks in a 24-hour period (χ2=4.64, df=1, p=0.031) were associated with larger inferior lateral ventricles. As previously demonstrated in this cohort (Kos et al, 2014; Olvera et al, 2011), lifetime nicotine dependence (h2=0.742, p=3.6x10-9), lifetime substance use disorder (h2=0.914, p=2.8x10-7), lifetime mood disorders (h2=0.493, p=1.1x10-4) and maximum drinks in a 24-hour period (h2=0.303, p=8.0x10-7) were heritable. Furthermore, these variables were genetically correlated with risk for AUD (nicotine dependence ρg=0.656, p=0.002; lifetime substance use disorder ρg=0.705, p=0.005; lifetime mood disorders ρg=0.818, p=0.001; and max drinks ρg=0.900, p=4.8x10-5), suggesting that common genes influence risk for AUD and smoking, substance misuse, and mood disorders. Despite the lack of a phenotypic effect, and given that shared genetic factors appear to influence these traits, including these measures as covariates could inadvertently minimize the effects of common risk genes, biasing results. References Duggirala R, Mitchell BD, Blangero J, Stern MP (1999). Genetic determinants of variation in gallbladder disease in the Mexican-American population. Genetic epidemiology 16(2): 191-204. Kos MZ, Glahn DC, Carless MA, Olvera R, McKay DR, Quillen EE, et al (2014). Novel QTL at chromosome 6p22 for alcohol consumption: Implications for the genetic liability of alcohol use disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. Mahaney MC, Blangero J, Comuzzie AG, VandeBerg JL, Stern MP, MacCluer JW (1995). Plasma HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and adiposity. A quantitative genetic test of the conjoint trait hypothesis in the San Antonio Family Heart Study. Circulation 92(11): 3240-3248. McKay DR, Knowles EE, Winkler AA, Sprooten E, Kochunov P, Olvera RL, et al (2013). Influence of age, sex and genetic factors on the human brain. Brain imaging and behavior. McPeek MS, Sun L (2000). Statistical tests for detection of misspecified relationships by use of genome-screen data. American journal of human genetics 66(3): 1076-1094. Mitchell BD, Kammerer CM, Blangero J, Mahaney MC, Rainwater DL, Dyke B, et al (1996). Genetic and environmental contributions to cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican Americans. The San Antonio Family Heart Study. Circulation 94(9): 2159-2170. Olvera RL, Bearden CE, Velligan DI, Almasy L, Carless MA, Curran JE, et al (2011). Common genetic influences on depression, alcohol, and substance use disorders in Mexican-American families. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 156B(5): 561568. Puppala S, Dodd GD, Fowler S, Arya R, Schneider J, Farook VS, et al (2006). A genomewide search finds major susceptibility loci for gallbladder disease on chromosome 1 in Mexican Americans. American journal of human genetics 78(3): 377392.