Notes on the Assignment of Morphological Case in Sakha

Two Modalities of Case Assignment in Sakha

Mark Baker and Nadya Vinokurova

Rutgers University

February, 2008

Abstract: There are two competing ideas about how morphological case is assigned in the recent generative literature. The standard view, developed by Chomsky, is that case is assigned by designated functional heads to the closest NP under an Agree relation. The alternative, proposed by Marantz 1991 and others, is that case is assigned to one NP if there is a second NP in the same local domain. We present evidence from the Turkic language Sakha that these two approaches to case theory are complementary.

Specifically, we argue that accusative case and dative case in Sakha are assigned by

Marantz-style configurational rules that do not refer to functional categories. Crucial evidence for this comes from passives, agentive nominalizations, subject raising, possessor raising, and case assignment in PPs. In contrast, nominative and genitive case are assigned by functional heads (T and D) in the Chomskian way; this is needed to explain the relationship between case marking and agreement in Sakha. We conclude that two distinct systems of case assignment can coexist peacefully, not only in Universal

Grammar, but even in the grammar of particular languages.

1. Introduction

In the generative syntax literature, there coexist two major ideas about how morphological case markers come to be associated with individual noun phrases in ways that reflect aspects of the syntactic structures those noun phrases appear in.

The more common idea is that structural case features are assigned to NPs by nearby functional heads. For example, nominative case might be assigned by (finite) T to the nearest NP that T c-commands. In a similar manner, accusative case might be assigned by (active, transitive) v to the nearest NP it c-commands, genitive case might be assigned by (possessive) D to the nearest NP, dative case might be assigned by (certain)

P(s), and so on. This is the view of Chomsky (2000, 2001) and his many followers

1

within the Minimalist Program. It is also the result of a fairly direct (although long and complex) line of development from the first Chomskian ideas about case assignment, presented in Chomsky 1981. This is the “governing” view that is usually adopted by generative researchers when their interests touch on case theory but it is not their primary area of study. See also Legate 2008 for a recent defense of this approach.

There is however an “official opposition” to this governing view, which has won a few seats in the Parliament of generative theory. This is the idea that case assigned to noun phrases on a configurational basis. More specifically, what case a particular NP has typically depends on this view on whether there are other NPs (“case competitors”) in the same local domain or not. For example, accusative case might be assigned to the lower of two NPs in a clause, whereas (in another language) ergative case is assigned to the higher of two NPs in a clause. If there is only one NP in the clause, a different case might be assigned—the unmarked case, nominative or absolutive. In this sort of theory, functional heads play no direct role in case assignment, although they play an indirect role in helping to define the relevant domains. (The notion “same clause” might be defined in terms of the projections of a designated functional head such as T, for example.) The first and purest proposal of this sort is by Marantz (1991). Bittner and

Hale’s (1996) rather intricate case theory also has this core idea as an important part of its inspiration. More recently, Marantz’s conception has been adopted in work by Bobaljik

(to appear), and is reasserted at length and developed by McFadden (2004), among others. It thus has some popularity among those linguists for Case theory is a primary object of study.

2

As far as we know, these two different conceptions of how morphological case works have always been conceived of as rivals, with each aspiring to capture all

(structural) case assignment phemonena in its own way. But it is logically possible that they are in fact complementary. That would be true if it could be shown that some cases are assigned by functional heads in the Chomskian way, whereas other cases are assigned by a configurational algorithm in Marantz’s sense. Moreover, there are two different grains of linguistic description at which this complementary could exist. The goal of this paper is to argue in favor of this last view, that the two modalities of case assignment not only coexist side by side in Universal Grammar, but they can even coexist internal to the same language. This we do by a relatively detailed analysis of case assignment in the

Sakha language (also called Yakuts), a Turkic language spoken in Northern Siberia.

Descriptively speaking, Sakha has four distinct cases that we take to be structural: nominative, accusative, dative, and genitive. Some very ordinary examples are:

(1) a. Min kel-li-m.

I-nom come-past-1sg

‘I came.’ b. Min yt-y kör-dü-m.

I dog-acc see-past-1sg

‘I saw the dog.’ c. Misha Masha-qa at-y bier-de

Misha Masha-DAT horse-ACC give-past.3

‘Misha gave Masha a horse.’

3

Our claim is that this four-case system divides neatly in half. Accusative and dative case are assigned by the configurational rules stated in (2).

(2) a. If there are two NPs in the same VP-phase and neither is marked for case, value the case feature of higher NP as dative. b. If there are two NPs in the same phase and neither is marked for case, value the case feature of the lower NP as accusative.

We assume the usual definitions of “higher” and “lower” in terms of c-command: NP X is higher than NP Y if and only if X c-commands Y, and NP X is lower than NP Y if and only if Y c-commands X. The rules in (2) are “Marantzian” in the sense that what is crucial for the assignment of case to a given NP is whether or not there is a second NP in the same domain or not, and if so what the relative structural configuration between the two NPs is. No direct role is attributed to which functional categories are present in local environment. In contrast, we claim that functional categories are deeply involved in the assignment of nominative and genitive case, as expressed in (3).

(3) a. T values the case of NP as nominative if and only if T Agrees with NP. b. D values the case of NP as genitive if and only if D Agrees with NP.

These are exactly the sorts of case assignment rules that are put forward in Chomsky

(2000, 2001), and we adopt his theory of the Agree relation. In this way, the elements of two prior theories are combined within the grammar of a single language.

1

There is a clear superficial difference between the two types of case in Sakha that gives our position some a priori plausibility. The Chomskian approach is built around the intuition that case and agreement are two sides of the same abstract linguistic relationship

(Agree), which holds between a functional head and a nearby noun phrase. Agreement

4

on the functional head is the transferring of phi-features from the NP to the functional head as a result of the relation being established, whereas case marking on the NP is the transferring of a case feature (or perhaps just a category feature) from the functional head to the NP as a result of the same relationship. For nominative and genitive, the idea that case and agreement are intimately related in this way is attractively transparent in Sakha: nominative NPs in a clause go along with subject agreement on the finite verb (see

(1a,b)), and genitive NPs within a DP go along with possessive agreement on the noun.

This is built into (3). But there is no comparable “object” agreement to make visible a relationship between an NP with accusative or dative case and any particular functional head; unlike nominative and genitive NPs, accusative and dative NPs are never agreed with in Sakha. This makes it not implausible, we think, that accusative and dative case are assigned in a different way from nominative and genitive, a way that does not depend on functional heads. In other words, the superficial different in overt agreement could in fact be a hint as to the two different modalities of case assignment that are at work here.

We present some stronger morphosyntactic arguments that this is correct.

We develop our argument as follows. First we provide some minimal morphological background in section 2. We then concentrate on the rules that assign accusative and dative case in (2), showing a range of phenomena that they account for and pointing out why these configurational rules are more satisfactory than the standard

Chomskian alternative (section 3). This exploration starts with simple transitive and ditransitive constructions, proceeds through causatives, anticausatives, passives, and nominalizations, ending with some complex data from a set of raising constructions. We then pose the question of whether case assignment in Sakha is configurational all the way

5

down. We argue that the answer is no (section 4). While it is not hard to give a

Marantzian account of nominative and genitive case in Sakha in isolation, this view does not explain the interaction between case and agreement that is found in the language. In particular, the Chomskian rules in (3) capture the broad generalization that it is never possible for two functional heads to agree with the same noun phrase in Sakha, whereas a

Marantzian alternative does not. We thus conclude that there are essentially two different case systems, coexisting peacefully in Sakha (section 4). Throughout the paper, we keep the attention entirely on Sakha, and make no claims about how case is assigned in other languages. Looking at Sakha itself is enough, we claim, to function as a sort of existence proof that both kinds of case assignment are attested in Universal Grammar; this then can form the basis for more typologically oriented studies in the future, which seek to learn about how these two kinds of case marking are distributed across languages.

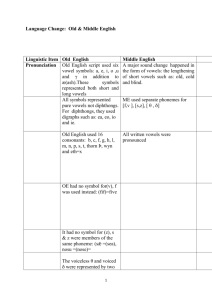

2. Background on the Morphology of Case

Some background will help the reader to understand the examples. Sakha is an SOV, head-final language with agglutinative morphology, rather free word order, and extensive vowel harmony. In these respects, it is not unlike its better-known relative, Turkish.

Much information about this language can be gleaned from Vinokurova 2005, which we build on and follow in many particulars, especially the work on accusative case in chapter

6. See also Krueger 1962 and Stachowski and Menz 1988 for basic information.

Accusative and dative case have relatively straightforward morphological exponents in Sakha, although both have many surface allomorphs as a result of phonological processes. Accusative case is generally marked by /I/ after a consonant and

6

/nI/ after a vowel, the high vowel harmonizing with the vowels of the stem in frontness and roundness, as in Turkish. Dative is generally marked by /kA/, with the nonhigh vowel undergoing harmony and the consonant also subject to various phonological changes. As in many languages, NPs in nominative case are morphologically unmarked, with no overt affix. In section 3, we take up the question of whether these NPs are assigned case in the syntax, which is spelled out with the null string in the morphology, or whether they are simply left uncase marked.

Genitive case was not illustrated in (1), because it raises some special morphological issues in Sakha. All other Turkic languages have a robust genitive case suffix (e.g.

–(n)In

in Turkish), but this has been largely lost in Sakha (Stachowski and

Menz 1998:421). As a result, an NP with genitive case is indistinguishable on the surface from an NP with nominative case in most environments. But there is an important exception. Many Turkic languages have special allomorphs of the case markers when they follow (third person) possessive agreement markers (Stachowski and Menz

1998:422). This is true for Sakha as well; for example, accusative is realized as /n/ after a possessive suffix, dative is realized as /qar/, and so on. Nominative is realized as /Ø/ even after the possessive suffix. But genitive is not; after a possessive suffix, the genitive is (like the accusative) realized as /n/ (Krueger 1962:77). The genitive in Sakha thus has no distinct endings of its own, but it can be seen to be different from nominative when the

NP in question is possessed and it can be seen to be different from accusative when the

NP is not possessed, as shown in (4).

(4) a. Masha-(Ø) öl-lö; Masha-(Ø) aqa-ta-(Ø) öl-lö.

Masha-NOM die-PAST.3sS Masha-GEN father-3s-NOM die-PAST.3sS

7

‘Masha died.’ ‘Masha’s father died.’ b. Min Masha-ny kör-dü-m; Min Masha-(Ø) aqa-ty-n kör-dü-m

Min Masha-ACC see-PST-1sS; Min Masha-GEN akha-3sP-ACC see-PST-1sS

‘I saw Masha.’ ‘I saw Masha’s father.’ c. Masha-(Ø) ata; Masha-(Ø) aqa-ty-n ata

Masha-GEN horse-3sP Masha-GEN father-3sP-GEN horse-3sP

‘Masha’s horse’ ‘Masha’s father’s horse’

We thus assume that genitive still exists as a distinct value of the case feature in Sakha syntax. The allomorphy of the case markers can be accounted for with in a Distributed

Morphology-like framework (Halle and Marantz 1993) by a system of morphological spell-out rules like those in (5).

(5) a. case

/GAr/ / POSS ____ [dat] b. case

/n/ / POSS ____ [acc/gen] c. case

/GA/ / ___[dat] d. case

/(n)I/ / ___[acc] e. case

Ø (elsewhere)

Other, more theory internal evidence for saying that genitive case still exists in Sakha can be seen in the coherence of the account that this allows us to construct in section 4 below.

For completeness, we note that Sakha also has several inherent cases, including ablative, instrumental, comitative, etc.. These are related to particular semantic roles, and never participate in syntactic alternations that we know of. Like most other investigators into case theory, we assume that this is a different phenomenon, and do not include it in our analysis. More specifically, we tentatively follow McFadden (2004) in assuming that

8

the inherent case markers are either postpositions themselves, or they are special cases assigned by various null postpositions. Some instances of dative case in Sakha also fall into this category—especially those on location and time-denoting expressions. (These bear locative case in other Turkic languages, but this form has also been lost in Sakha

(Stachowski and Menz 1998:421).)

3. The configurational case marking of objects

We begin with demonstrating the virtues of the configurational rules for the assignment of dative and accusative case given in (2). Our exposition moves from the relatively simple and straightforward data, for which Sakha is no different from many other languages, to the more complex and surprising data, where the advantages of our proposal can be seen the most clearly.

3.1 Simple active sentences

It comes as no surprise that the objects of simple active dyadic predicates in Sakha are marked in accusative case, triadic predicates have one object in accusative case and one object in dative case, and the subjects of most predicates bear neither accusative or dative. (1) presented some relevant examples; (6) gives a few more.

(6) a. Min ülel-ii-bin.

I-nom work-aor-1sg

‘I worked.’ b. Erel kinige-ni atyylas-ta.

Erel book-acc buy-past.3

‘Erel bought the book.’

9

c. Masha aqa-ty-gar suruk-u yyt-ta.

Masha father-3sP-DAT letter-ACC send-PAST.3

‘Masha sent her father a letter.’

And, not surprisingly, these simple patterns follow from our rules in (2). In sentences like (6c) there are two NPs inside the VP. Therefore the structurally higher one—the goal argument—is marked dative by (2a).

2

In sentences like (6b) there is only one NP in the VP domain, the subject being generated outside VP in Spec, vP. Therefore, (2a) does not apply. Nor does (2b) apply in the VP domain, since there is only one NP in VP. The clause as a whole does contain more than one NP, however. Hence (2b) applies on the

CP phase/cycle, marking the lower NP (the direct object) as accusative.

A technical detail of the rules in (2) helps to account for a somewhat less trivial property of case marking in Sakha. Like Turkish and quite a few other languages, Sakha is a differential object marking language—a language in which not all direct objects bear the same kind of case marking. The accusative case marker –(n)I only appears on NPs that receive a definite and/or specific interpretation (Vinokurova 2005:322). When the thematic object is indefinite, then it bears no case suffix, as shown in (8).

(7) a. Erel kinige atyylas-ta.

Erel book-Ø buy-past.3

‘Erel bought a book/books.’ b. Min saharxaj sibekki-(ni) ürgee-ti-m.

I yellow flower-(acc) buy-past-1sg

‘I picked (the/a certain) yellow flower(s).’

10

A way of capturing this phenomenon emerges from (2) if we assume that the locality domains in which case competition is evaluated are crucially phases in something like

Chomsky’s sense. There are two phases in an ordinary clause, CP and (let us assume)

VP.

3

The indefinite object stays strictly inside the VP phase, and so is never in the same domain as the subject. Since the object and the subject each are the only NPs in their respective domains, both are left unmarked by the rules in (2). In contrast, definite objects undergo object shift, away from the verb, to escape the domain of existential closure (Diesing 1992 and much related work). This movement places the object inside the same domain as the subject. The two now count as case competitors for one another, and accusative case is assigned to the lower NP, the object as shown in (9b). (Notice that it does not matter for these purposes whether the subject moves to Spec, TP or not.)

(8) a. [[ Erel [

VP

book buy ] v ] T ]

phase 1 phase 2

(=(6b)) b. [[ Erel [

VP

book [

VP

t buy ] v ] T ]

phase 2 phase 1

(=(7a))

Some support for this view that syntactic movement plays a role in whether an object is marked accusative or not comes from the interaction of case marking and word order with respect to adverbs. Objects that are not marked for case must follow VPadverbs like ‘thoroughly’ and ‘quickly’ whereas objects with accusative case come before this class of adverbs in the unmarked order; the paradigm in (8) is typical.

(9) a. Masha salamaat-*(y) türgennik sie-te.

Masha porridge-ACC quickly eat-past.3

‘Masha ate the porridge quickly.’ b. Masha türgennik salamaat-(#y) sie-te.

11

Masha quickly porridge-acc eat-past.3

‘Masha ate porridge quickly.’

Accusative on ‘porridge’ only if it bears contrastive focus

Assuming that these adverbs are generated at the left edge of the VP, they reveal whether the movement shown in (7) has happened or not, and show that this movement determines the case marking in the manner described in (2b). One complication—which we take to be minor—is that accusative case marking on the post adverbial object in (8b) is not strictly impossible, but is given a special interpretation, as having contrastive focus on the accusative-marked object. We tentatively assume that this is not a syntactically simple structure; rather this particular surface string can only derived by a series of movements into the Left Periphery, driven by considerations of focus and topic movement (see Vinokurova 2005:xx for a possible derivation).

The same dependence of accusative case marking on object shift can be seen in ditransitive clauses in Sakha. The goal in such clauses is always marked dative, whereas the theme can be unmarked or accusative depending on both its specificity and its position with respect to the goal. When the theme is unmarked for case, it must be a nonspecific indefinite and must follow the goal; when the theme is marked for case, it is specific or definite and comes before the goal unless additional, focus driven movements also take place:

(10) a. Min Masha-qa kinige-(#ni) bier-di-m.

I Masha-DAT book-ACC give-PAST-1sS

‘I sent Masha books/a book.’ b. Min kinige-*(ni) Masha-qa bier-di-m.

12

Masha book-ACC Masha-DAT give-PAST-1sS

‘I gave the book to Masha.’

Prior to any (relevant) movement, the theme and the goal/benefactive are both in VP, with the goal/benefactive c-commanding the theme. (This can be shown using standard

Barss-Lasnik-Larson tests involving pronominal binding (Barss and Lasnik 1986, Larson

1988).) (2a) then assigns dative to the goal/benefactive NP on the VP cycle. (2a) is ordered before (2b) by the general (Paninian) ‘Elsewhere’ condition, because (2a) is a more specific rule than (2b), limited to applying in only one kind of phase (VP). Once

(2a) applies, it has the effect of bleeding the application of (2b) in the VP cycle, since only NPs that are unmarked for case are visible to the case competition. Hence, the theme is not automatically marked accusative simply by virtue of being in the same VP as the goal. If no movement happens, then the theme never enters the CP phase, (2b) never applies, and accusative case is not assigned. This results in sentences like (9a).

Alternatively, the theme NP can undergo object shift to the edge of the VP phase, thereby crossing the goal and escaping the domain of existential closure. If it does, then it is visible on the CP phase, as is the subject Masha. The two are case competitors, and accusative is assigned to the theme, the lower of the two NPs. In this way, examples like

(9b) are derived.

(11) a. [[ Erel [

VP

Masha-DAT book buy ] v ] T ]

phase 1 phase 2

(=(10a)) b. [[ Erel [

VP

book-ACC [

VP

Masha-DAT t buy ] v ] T ] (=(10b))

phase 2 phase 1

Note that it may well be possible to move the goal NP out of the VP proper into the CP phase, for reasons of specificity or whatever. However, this will not affect its case

13

marking, because it is already marked as dative by (2a) on the VP cycle, and such case marking is indelible (see section 4). It thus follows from our rules that there is differential object marking in Sakha, but not “differential indirect object marking.”

Given that movement of the object into the CP phase can feed accusative case marking, we need to consider what happens when the object moves to a higher position than the thematic subject. This kind of “scrambling” may not be as common in Sakha as it is in Japanese and some other head final languages, but it is possible, as shown in (12).

(12) Deriebine-ni orospuonnjuk-tar xalaa-byt-tar. village-acc robber-pl raid-RepPast-pl/*raid-RepPast

‘Some robbers raided the village.’

Notice that, in point of fact, the case marking does not change with the word order: it is the object that is marked accusative in (12) (as in (1b) and (6b)), and not the subject. In fact, (2b) might predict accusative case marking on the subject if the object moved directly to the highest position in the clause. Fortunately, though, the logic of phase theory comes to the rescue, ruling out direct movement. Chomsky’s Phase

Impenetrability Condition tells us that a NP can only move from inside a phase like VP into a higher phase by first moving to the edge of the lower phase. Given this, a sentence like (12) must have a representation in like in (13).

(13) [

TP

village [

TP

robbers ... [

VP

<village> [

VP

<village> raid]] -PAST ]]

phase 2 ACC phase 1

There must thus be an occurrence of ‘village’ that is lower than the subject ‘robbers’ and yet accessible on the CP cycle, as well as the visible occurrence of ‘village’ that is higher than ‘robbers’. (2b) will apply at the point of the derivation when ‘village’ is at the edge

14

of VP and lower than the thematic subject, assigning ‘village’ accusative case.

4

That case is then carried along if ‘village’ undergoes further movement. Since case marked NPs don’t count as case competitors, the scrambled accusative object doesn’t induce accusative case on the subject, even after it moves to a position higher than the subject.

This reasoning also applies to other kind of movement of the object into the CP domain: hence the wh-movement (for example) relative clauses also does not affect the assignment of accusative case in Sakha.

Of course, these data do not distinguish our configurational theory of accusative and dative case assignment from the view that accusative case (at least) is assigned by the functional head v. All these facts have familiar analyses in that framework. So far, all we have done is show that the configurational rules in (2) are contenders.

3.2 Case marking of thematic subjects

It is an elementary consequence of a case competition account like (2) that truly monadic predicates should never have accusative or dative case arguments in Sakha. This follows because the rules in (2) only assign accusative or dative case to an NP if there is another

NP in the same domain, and that will never be the case if the predicate is monadic. And indeed we know of no intransitive verbs that take dative or accusative subjects in Sakha; even verbs with experiencer arguments have nominative subjects:

(14) Masha-(*qa/*ni) accykt(aa)-yyr.

Masha-(*DAT/*ACC) hunger-aor

‘Masha hungers.’

Sakha is different in this regard from languages like Icelandic, which has a good number of one-place predicates with quirky-case subjects.

15

In contrast, the rules in (2) do permit the possibility that there could be special dyadic predicates that have dative case “subjects” in Sakha. This could arise when two

NPs are generated inside VP, but there is no NP with an agent role generated in Spec, vP.

In that situation, dative case would be assigned by (2a) to the highest thematic position in the clause, resulting in a dative NP that might act like a grammatical subject in some respects. Sakha does not have many predicates like this, in comparison with other languages. Psych verbs, for example, consistently have a nominative-accusative case frame, like Modern English and not Icelandic. But Sakha does have a handful of dative subject verbs from other semantic domains, including baar

, ‘have’ and naada ‘need’:

(15) a. Ej-iexe massyyna baar. exist you-DAT car

‘You have a car.’ b. Miexe massyyna naada. need. I-DAT car

‘I need a/the car.’

There is binding evidence that the dative arguments in these sentences c-command the bare arguments, and not vice versa, so they are worthy of being called dative subjects.

5

Note also that the lower argument in these sentences is unmarked, not accusative, as expected given that when (2a) applies it bleeds the application of (2b), as we already saw in our discussion of ditransitive constructions.

There is one other, more systematic circumstance in which a thematic subject can be assigned accusative or dative case: this is in morphological causative constructions.

Sakha has a productive causative suffix –t/-tar that attaches to many different kinds of

16

verb roots. As in many other languages, when an intransitive verb appears in the causative construction, its thematic subject is marked with accusative case (if it is definite or specific); when a transitive verb appears in the causative construction, its thematic subject can be marked with dative case (see Vinokurova 2005:306-312 for more examples):

6

(16) a. Sardaana Aisen-y/*qe yta(a)-t-ta. (compare: Aisen ytaa-ta)

Sardaana Aisen-acc/*DAT cry-caus-past.3

‘Sardaana made Aissen cry.’ b. Misha Masha-qa miin-i sie-t-te.

Aisen cry-past.3

‘Aissen cried.’

Misha Masha-DAT soup-(ACC) eat-caus-past.3

‘Misha made Masha eat (the) soup.’

This follows readily from the case-marking rules in (2). Agent phrases are usually the highest NPs in the clause, and they aren’t contained in VP; hence they usually do not qualify for dative or accusative case. But the causative morpheme is an additional predicative element; it integrates the agent of the verb root into a larger VP that it heads, and it licenses a still higher argument, the causer. Since, the agent of the base verb is now contained in the maximal VP, it receives dative case if (and only if) there is another, lower NP inside that VP—in other words, if and only if the base verb is transitive. If the lower verb is not transitive, then the agent of the lower verb is the only NP inside the VP headed by the causative morpheme. If it stays inside the VP, it remains unmarked, but if it shifts to the edge of the VP to receive a definite or specific reading, then it enters the same domain as the higher causer NP; then the lower agent is marked accusative. Many

17

different structures have been proposed for morphological causative constructions, and many of them would fit fine with this analysis; perhaps the simplest is the one in (17).

(17) a. [[ vP

Sardaana [

CausP

Aisen [

VP

cry ] cause ] v ] Past ]

phase 2 (ACC) phase 1 b. [[ vP

Masha [

CausP

Misha [

VP

soup eat ] cause ] v ] Past ]

phase 2 DAT (ACC) phase 1

The fact that dative case is used on the causee if and only if there is another lower NP is perhaps the strongest reason for saying that dative case can be a structural case in Sakha, since it is not so plausible to say that the agent NP is theta-marked by a null postposition in this structure and only this structure.

Although this range of facts fits well with our configurational rules of case assignment, there are still familiar ways of capturing them within the theory that has case assigned by functional heads as well. So we have still not found evidence that chooses between these two approaches. We are now however ready to consider those areas in which case assignment in Sakha is somewhat different from that of more familiar languages—areas in which the distinctive advantages of (2) become more clear.

3.3 Passive and case assignment

Like many other languages, Sakha has (at least) two distinct detransitivizing constructions, the anticausative and the passive. (18) shows a simple transitivity alternation, with (18b) the detransitivized, anticausative member of the pair (Vinokurova

2005:285).

(18) a. Min oloppoh-u aldjat-ty-m.

I chair-acc break-past-1sg

18

‘I broke the chair.’ b. Caakky/*Caakky-ny aldjan-na. cup/*cup-acc break-past.3

‘The cup broke.’

Note that the theme argument cannot be marked accusative in (18b), whereas it can be in

(18a). This is entirely expected: the intransitive version of ‘break’ does not have an agent generated in Spec, vP. As a result, there is thus no case competitor for the theme argument in the CP phase, and it is not marked accusative by (2b).

What is interesting about this is that it contrasts with the passive. Unlike the anticausative in Sakha and the passive in familiar Western European languages, the theme argument in a Sakha passive can be marked accusative, although it can also be nominative (Vinokurova 2005:336-338) as shown in (19).

(19) a. Caakky/Caakky-ny aldjat-ylyn-na. cup-Ø/cup-acc break-pass-past.3

The cup was broken. b. Kinige/kinige-ni aaq-ylyn-na. (compare (6b)) book-Ø/book-acc read-pass-past.3

‘The/a book was read.’

In fact, it is not entirely unexpected that there would be such a difference, given our proposal. Whereas the agent argument is completely suppressed in anticausatives, it is well-known that the agent of a passive sentence can still present syntactically and semantically in various ways (e.g., the well-known contrast * The ship sank to collect the insurance vs. The ship was sunk to collect the insurance ). Thus we can say that, since

19

the agent is still present in the passive—say as a PROarb, in the specifier of the v headed by the passive morpheme (Collins xxx)—it can still count as a case-competitor for the definite object, triggering accusative case on it. In contrast, there is no agent phrase that c-commands the theme at any syntactic level of representation in an anticausative. It thus follows that theme cannot be accusative in (18b).

In fact, essentially the same contrast can be seen internal to the passive construction in Sakha. Vinokurova 2005:336 compares passives that have an accusative theme with passives that have a nominative theme. She shows that passive clauses with an accusative theme show clear implicit argument effects: they can contain purposive clauses, agent-oriented adverbs, instrumental phrases, and the like. In contrast, passives in which the definite/specific theme is marked nominative show no such signs of having an implicit agent argument: 7

(20) a. *Caakky sorujan ötüje-nen aldjat-ylyn-na. cup intentionally hammer-instrum break-pass-past.3

‘The cup was intentionally broken with a hammer.’ b.

Caakky-ny sorujan ötüje-nen aldjat-ylyn-na. cup-acc intentionally hammer-instrum break-pass-past.3

‘The cup was broken intentionally with a hammer.’

We thus posit representations like those in (21) for the sentences in (20).

(21) a. [[ vP

-- (*intentionally) [

VP

cup [

VP

t break ]] PASS/AC ] past ] b. [ vP

PRO arb

(intentionally) [

VP

cup-ACC [

VP

t break ]] PASS ] past

Given this sort of difference in representation, the rule in (2b) applies as written to assign accusative case to cup in (21b) but not in (21a).

20

This configurational account can be compared with the standard view in which accusative case is assigned by v. Most of the same results follow, given the usual stipulation that only theta-role assigning v assign Acc case (Burzio’s Generalization)

(Burzio 1986). But the standard view would have to apply Burzio’s Generalization in a particularly strong way. For these data, it is not enough that there be a general correlation between functional heads that assign accusative case and functional heads that license an agent role in the syntax. Rather, there has to be a very specific correlation, such that what looks like the very same functional head (the passive voice marker) assigns accusative case when it has an NP in its specifier position and not when it doesn’t. As always with

Burzio’s Generalization, there is no obvious conceptual reason why these two logically distinct properties of v should be packaged together in this way. This makes more conceptual sense within a case competition theory such as (2). The data suggest that it is not what functional heads are present that is crucial, but whether a second noun phrase is present, and (2) expresses why this should be much more directly and reasonably.

Finally, consider the assignment of dative case in passive clauses in Sakha.

Unlike accusative case, dative case is unaffected by passive morphology in Sakha. When a triadic verb is passivized, the argument that would have been dative in the active sentence is still dative in the passive sentence, while the argument that would have been accusative can either be accusative, as in (22), or unmarked nominative, as in (23).

(22) Masha-qa surug-u yyt-ylyn-na.

Masha-DAT letter-ACC send-PASS-PAST.3

‘Masha was sent a letter.’

(23) Suruk Misha-qa yyt-ylyn-na.

21

letter Misha-DAT send-PASS-PAST

‘The letter was sent to Misha.’

Alternative structures in which the goal argument is marked nominative in a passive are generally rejected by native speakers (e.g. *Masha suruk yyt-ylyn-na (Masha letter send-

PASS-PAST.3) ‘Masha was sent a letter.’)

8

This pattern is just what is predicted by the rules in (2). The replacement of an active v by a passive one can affect whether there is an agent argument in vP. However, it has no effect on the internal structure of VP. Since dative case is assigned to the higher argument on the VP domain, it is assigned in the same way regardless of what sort of v head is merged later, an active one or a passive one. Continuing to assume that dative case-marking is indelible, it follows that the same argument gets dative in a passive sentence as in an active one. In the meantime, whether the theme object is marked accusative or not depends on two factors—whether it object shifts out of VP, and whether there is a PROarb in Spec of the passive voice phrase—exactly as in simple transitive structures with no third argument. A relevant structure would be as shown in (24).

(24) [[ vP

(PRO) [

VP

letter [

VP

Misha t i

send ]] PASS ] PAST]

(ACC) DAT

phase 2 phase 1

Notice that in our theory there is no need to stipulate that passive morphology

“absorbs” structural accusative case but not structural dative case, as was done in some

GB-era versions of case theory. This asymmetry in the two kinds of case assignment follows directly from the basic formulation of the two rules in (2)—particularly the fact that dative case assignment happens on the VP cycle, whereas accusative assignment happens on the CP cycle.

22

3.4 Agentive nominalizations

Consider next case assignment in agentive nominalizations. Sakha has a productive morpheme aaccy , which is used to derive agentive nominals from verb roots; it is similar in many respects to the derivational morpheme er in English (Vinokurova 2005:123-124).

But there is one striking difference: unlike in English, the thematic object of such a nominalization has accusative case, as shown in (25).

(25) a. Masha [ynaq-y kör-ööccü- nü] najmylas-ta

Masha Cow-ACC watch-aaccy-ACC hired

‘Masha hired a cowherd.’ b. [Terilte-ni salaj-aaccy] kel-le company-acc manage-AAccY come-past.3

‘The manager of the company came.’

In English, we normally say that accusative case is not available for the object of the nominalized verb because the verbal functional head v that assigns that case is absent in these structures; they contain nominal functional heads like number and determiner, but not verbal ones. Where then does the accusative case come from in Sakha?

One might try to save the functional head theory of case assignment by saying that the structure of the agentive nominals is different in Sakha from in English. Perhaps in Sakha the nominalizing morpheme selects not for a bare VP, but rather some larger extended projection of the verb, that includes the assigner of structural case. In the domain of event-denoting nominalizations, this a familiar possibility: many languages have both “derived nominals” and “gerunds”, where the latter contains more verbal structure than the former (

Rome’s vicious destruction of Carthage

, versus

Rome’s

23

viciously destroying Carthage ). The problem is that there is, apparently, no similar distinction in the domain of agent-denoting nominals: for example, English has the vicious destroyer of Carthage but nothing like * the viciously destroyer Carthage . Sakha is like English in this respect: other than the accusative case assignment under study, there is no sign that agentive nominals contain any verbal/clausal structure higher than the verb root. For example, vP-internal adverbs are not felicitous in agentive nominals:

(26) a. (*Ücügejdik) terilte-ni (*ücügejdik) salaj-aaccy kel-le.

(*well) company-acc (*well) manage-AAccY come-past.3sg

‘The one who manages the company well came.’ b. djie-ni (*bütünnüü/*xat) kyraaskal-aaccy house-ACC (*completely/*again) paint-AACCY the painter of the house (*completely) (*again)

Also impossible in this kind of nominalization are aspectual suffixes ((27a)), negation

((27b)), and passive morphology ((27c)).

(27) a. *Suruj-baxt(aa)-aaccy kel-le write-ACCEL-AG.NOM come-PAST

‘A quick writer came.’

(no aspectual suffix) d. *Suruj-um-aaccy kel-le. (no negation) write-NEG-AG.NOM come-PAST.3

‘The one who doesn’t write came, the non-writer came.’ e. *tal-yll-aaccy (no voice morphology) choose-PASS-AG.NOM

‘the one who is chosen’

24

So agentive nominals in Sakha do not contain an extended verb phrase structure the way that gerunds do in English and other languages (including Sakha).

Based on facts like these, Baker and Vinokurova (2007) analyze –AAccY as a nominal head that selects a VP complement and no more, as shown in (28).

(28)

NP

VP N

NP V -aaccy

<agent>

cow watch

<theme>

There is no sign of a v in a structure like (28) that can assign accusative case to the NP object—a problem for the Chomskian case theory. In contrast, the configurational case theory based on the notion of case competition does not depend on there being certain functional categories present. As long as there is some syntactic realization of an agent distinct from the theme argument, that could be enough to trigger accusative on the object. We assume that there is such a syntactically represented agent in these nominals.

There are two possibilities as to what it is: it could be an empty category such as PRO arb in the specifier of aaccy

, parallel to the “implicit agent” found in passive sentences, or it could be the nominal head –AACCY itself. We leave open which of these is correct.

Note that differential object marking occurs in agentive nominals too. For example, (29) is possible without accusative case marking on the thematic object ‘cow’:

(29) Ynax-(y) kör-ööccü cow-(ACC) kel-le watch-NOM come-PAST

25

‘The watcher of (the) cow(s) came.’

Moreover, the alternation seems to be keyed to definiteness/specificity, just as it is in clauses. With accusative case, the subject in (29) refers to a person who has been put in charge of a specific cow; without accusative case it can mean someone who has the profession of watching cows in general. Thus, given the logic of our account of differential object marking in clauses, the VP in (28) must also count as a phase distinct from any phase defined by the NP (or DP) as a whole. If the object NP stays in this phase, (2b) does not apply and the object remains unmarked for case. But object shift can optionally apply, moving the object to the edge of the phase so that it is visible in the same domain as the nominalizer –aaccy itself. Then (2b) does assign accusative case.

Finally, consider dative case assignment in agentive noun phrases in Sakha.

Given that they have a VP node (although no higher verbal structure), dative case assignment should be a possibility whenever there are two unmarked DPs in the VP.

This is a correct result: dative case is possible on the goal argument when an agentive nominalization is formed from a ditransitive verb, as in (30).

(30) oqo-lor-go emp bier-eecci ol tur-ar

Children-DAT medicine give-AACCY there stand-AOR

A giver of medicine to children is over there.

However, when we include freely generated benefactive expressions in the picture, we find a contrast that is not apparent in the clausal domain. When the nominalized verb is transitive, including a dative expression is sometimes possible as in (30), but when the verb is an unergative verb, the benefactive expression is at best awkward:

(31) a. ?/??/*Masha-qa ülelee-cci kelle.

26

Masha-DAT work-AACCY came

The one who works for Masha came, The worker for Masha came.

(OK: Masha-qa work-AOR-1sS ‘I work for Masha’) b. ??preside

ŋ-ŋa kömölöh-ööccü

??President-DAT help-AACCy

The helper of the president.

(OK: pres-DAT help-AOR-1sS ‘I help the president’)

We take this to be support for our case assignment rule in (2a), which says that structural dative case is assigned to an NP only if that NP c-commands a distinct NP within the VP.

That condition is satisfied in (30), but it is not satisfied in (31); there is no other NP that the benefactive c-commands to justify it having dative case. Unergative verbs like

‘work’ can appear with dative case NPs in clauses, but we conjectured (see note 5) that this was not the result of structural dative case assigned by (2a); rather it was inherent dative case assigned by a null P. Now many languages do not permit a PP to modify an

NP, and Sakha is one of these:

(32) *ambaar-y tula k ürüö

*barn-ACC around fence

‘the fence around the barn’

Having a benefactive PP in the nominal domain is thus ruled out on independent grounds.

9

As a result, the only kind of dative case that can appear inside a nominal is structural dative case. The contrast between (30) and (31) thus supports the idea that structural dative case depends on there being a case competitor—a truth we already observed in morphological causatives and dative subject constructions.

27

3.5 Raising of Subjects in Sakha

We come now to perhaps the most spectacular evidence in favor of the case competition account of accusative case assignment in Sakha: the “raising to object” construction described in Vinokurova 2005:sec. 6.10, but not fully explained there. Vinokurova shows that an NP that moves into the matrix clause can be marked with accusative case.

Such movement is possible out of both finite and nonfinite clauses:

(33) a. Min ehigi/ehigi-ni bügün kyaj-yax-xyt dien erem-mit-im.

I you/you-ACC today win-FUT-2pl that

‘I hoped you would win today.’ b. Min ehigi/ehigi-ni bügün kyaj-byk-kyt-yn hope-PAST-1sg ihit-ti-im.

I you/you-ACC today win-PTPL-2pl-ACC heard-PAST-1sg

‘I heard that you won today.’ (p. 361)

Vinokurova gives evidence that the subject of the embedded clause leaves the embedded clause and enters the matrix clause if and only if it is marked with accusative case. Her evidence comes from word order with respect to adverbs that modify the matrix verb, and from negative polarity licensing, which is strictly clause bound in Sakha:

(34) a. Sardaana (Aisen-y) beqehee [bügün (*Aisen-y) kel-er dien] ihit-te.

Sardaana (A.-ACC) yesterday today (A.-ACC) come-AOR that hear-past.3

‘Sardaana heard yesterday that Aissen is coming today.’(p. 363) b. Min kim-i daqany kyaj-da dien isti-be-ti-m.

I who-ACC PRT win-PAST.3 that hear-NEG-PAST-1sg

‘I didn’t hear of anybody that they won.’ (p. 364)

28

The judgments reverse if accusative case is not marked on the thematic subject of the lower verb: then Aisen is only possible after the higher time adverb ‘yesterday’, and the negative polarity item kim daqany is only possible if negation is on the lower verb.

At first glance, it would seem that either the case competition theory or the assignment by functional head theory could explain this sort of data. Within a competition theory, raising the subject from the embedded CP into the matrix CP places it in the same phase as the subject of the matrix clause. Rule (2b) then applies to mark the lower subject as accusative. Within a functional head theory, one might suppose that accusative case is assigned by the v of the matrix clause; raising the subject takes it out of the lower CP phase and makes it close enough to v to be case marked by it. Both accounts are natural enough, and attribute the effect to the PIC in similar ways.

What is striking, however, is that raising to object can take place even when there is no functional head in the matrix clause which could be the source of accusative case.

(35) shows raising into a matrix clause whose predicate is the intransitive member of a transitivity alternating verb ( xomot ‘make sad’ vs. xomoj ‘become sad’; tönnör

‘make return’ vs. tönün

‘return’), hence an unaccusative verb.

(35) a. Keskil Aisen-y [kel-be-t dien] xomoj-do.

Keskil Aisen-ACC come-NEG-AOR that become.sad-past.3sS

Keskil became sad that Aisen is not coming. (p. 366) b. Masha Misha-ny [yaldj-ya dien] tönün-ne

Masha Misha-ACC fall.sick-FUT that return-PAST.3sS

‘Masha returned (for fear) that Misha would fall sick.’

29

The v associated with these unaccusative verbs cannot assign accusative case on standard assumptions; if it did, the standard theory would lose its account of (18b). Nevertheless, accusative case marking in (35) is possible. Similarly, (36) shows that an NP can raise out of the embedded clause and be marked with accusative case even when the matrix verb is a passive with no implicit agent argument.

(36) Sargy Masha-ny [t tönn-üö dien] erenner-ilin-ne.

Sargy Masha-ACC [t return-FUT dien] promise-PASS-past.3

‘Sargy was promised that Masha would return.’

This datum too is unexpected on the standard view that accusative case is assigned by a particular functional head (i.e. transitive v).

In contrast, the case competition view easily extends to the data in (35) and (36).

When the subject of the lower clause raises into the higher clause, it enters the same domain as the (derived) subject of the matrix clause. This NP is a case competitor for the raised subject, licensing the accusative case marking on it. Functional heads do not come into the account; all that matters is that there is another noun phrase in the matrix clause.

It is also possible for an NP to get accusative case by moving to the edge of an adjunct clause.

10 (37) gives examples of this kind. Note that this can happen even when the matrix clause is transitive. The result is two distinct accusative case marked noun phrases, something that is otherwise extremely limited in Sakha.

(37) a. Masha [Misha-ny kel-ie dien] djie-ni xomuj-da.

Masha [Misha-ACC come-FUT that] house-ACC tidy-PAST.3

‘Masha tidied up the house (thinking) that Misha would come.’ (p. 368) b. Masha Kesha-qa [Misha-ny aaq-ya dien] kinige-ni bier-de.

30

Masha Kesha-DAT [Misha-ACC read-FUT that] book-ACC give-past.3

‘Masha gave Kesha the book so that Misha would read it.’ (p. 368)

These examples are awkward for the view that case is assigned by functional heads, because there is only one transitive v that could be a source for accusative case in the matrix clauses in (58). Given that case assignment by a functional category is usually one-to-one, this v cannot assign case both to the object of the matrix verb and the raised subject of the embedded verb. (If one changed this assumption, then it would be hard to explain why the two objects of a simple triadic verbs like give and send cannot both be assigned accusative case in Sakha; compare section 3.1 above.) In contrast, the case assignment rule in (2b) does not lead to any expectation that accusative case assignment must be unique. It is perfectly imaginable that there will be two NPs that move into a single CP domain, both of which are c-commanded by a third NP that is base-generated in that higher domain. Then both will be marked for accusative case. That is precisely what we see in (37), where subject raising and object shift both feed accusative case assignment in the same clause.

There is one very instructive situation in which an NP raised out of an embedded clause cannot be marked as accusative. That is when the matrix clause is an impersonal predicate like ‘be certain’ or ‘be necessary’, which has at most an expletive subject.

Raising NP out of the clausal argument of these predicates is possible, as shown by order with respect to adverbs. Nevertheless, the raised NP in these circumstances must be unmarked for case, and cannot have the accusative suffix:

(38) Masha/*Masha-ny bügün munnjax-xa [ehiil Moskva-qa bar-ar-a] cuolkaj buol-la.

31

Masha/*Masha-acc today meeting-dat [next.year Moscow-dat go-aor-3] certain be(come)-past.3

‘It became clear today at the meeting that Masha will go to Moscow next year.’

Thus while the transitivity of the matrix verb is not crucial to the licensing of accusative case, it is crucial that there be a competing NP in the matrix clause. This is important confirming evidence in favor of the case competition account.

Finally, consider the implications of subject raising for the dative case assignment. Vinokurova 2005:367 observes that when the subject of the complement clause of a verb like ‘promise’ raises into the matrix clause, the other internal argument of ‘promise’ cannot be marked accusative, but must be marked dative:

(39) Sargy Keskil-i [Aisen kel-ie dien] erenner-de.

Sargy Keskil-ACC Aisen come-FUT that promise-PAST.3

‘Sargy promised Keskil that Aissen will come.’

(40) Sargy Keskil-ge/*i Aisen-y [ t kel-ie dien] erenner-de.

Sargy Keskil-DAT/*ACC Aisen-ACC come-FUT that promise-PAST.3

‘Sargy promised Keskil that Aissen will come.’

Our case assignment rules put us in a position to understand why this is. The clausal complement of ‘promise’ is its innermost argument; it is generated inside the matrix VP.

When an NP raises to the edge of this CP, it becomes visible in the matrix VP phase. The matrix verb is ‘promise’ also selects for an NP argument, which is also inside the VP—a goal-like argument that expresses the one who is promised. This goal argument ccommands the clausal argument, and it c-commands the subject NP that has raised to the edge of the CP. The conditions specified by (2a) thus apply, and dative case is assigned

32

‘promise’s NP argument. From the edge of the embedded CP, the subject of the lower clause can move on to the edge of the matrix VP; when it does, it becomes visible in the matrix CP phase, and is marked accusative because it is c-commanded by the matrix subject. What is not possible is for the lower subject to be marked accusative without the promisee being marked dative. That would require the lower subject to move directly from the lower CP phase into the higher CP phase, without entering the matrix VP phase; such a derivation would violate the Phase Impenetrability Condition. In contrast, the adjunct clauses in (37) are generated outside the matrix VP, and are not c-commanded by the internal argument of the matrix verb. When NP raises to the edge of the adjunct clause, it does not become visible on the matrix VP phase, but only on the matrix CP phase. Hence, raising from an adjunct clause does not feed dative case assignment inside

VP, whereas raising from a complement clause can.

We take all this to be good support that the various details of our proposal fit together in the appropriate way. We think it would be very difficult for a classical theory in which case is assigned by designated functional heads to capture this range of facts.

3.6 Raising of Possessors

Sakha has second kind of raising construction, which is somewhat similar to the subject raising construction, but which also has some important differences. This is the so-called possessor raising construction. Vinokurova (2005:146-151) discusses it only for the existential predicate baar , but it is possible with a wide selection of unaccusative verbs.

This construction provides some further support for our dative case assignment rule.

It is of course possible for a possessor to form a constituent with the possessed NP in Sakha. When this happens, the possessor is contiguous with the possessed NP, and the

33

possessor is in genitive case (unmarked and homophonous with the nominative, except when the possessor itself is possessed). A simple base-line examples of this is (41).:\

(41) Beqehee Misha at-a

öl-lö. yesterday Misha-dat horse-3 die-past.3

‘Misha’s horse died yesterday.’

But under certain conditions, it is also possible for the possessor to raise out of the possessed NP, so that it is separated from the possessor by (for example) an adverbial modifier of the matrix clause. When this happens, the raised possessor can either bear dative case, as in (42), or unmarked nominative case, as in (43).

(42) a. Misha-qa beqehee at-a öl-lö.

Misha-dat yesterday horse-3 die-past.3

‘Misha’s horse died on him yesterday.’ b. Masha-qa beqehee vaza-lar-a aldjan-na/aldjan-ny-lar.

(43)

Masha-DAT yesterday vase-pl-3 break-past.3/break-past-pl

‘Masha’s pots broke on her yesterday.’ a. Masha aaspyt tüün yt-a

öl-lö. die-Past.3 Mash a last.night

Masha’s dog died last night. dog-3s b. Masha emiske massyyna-ta aldja-n-na

Masha suddenly car-3s

‘Masha’s car suddenly broke down.’ break-INT-PAST.3sS

34

Prima facie evidence that these are raising constructions comes from the fact that they are impossible if there is no possessive agreement on the head noun of the theme argument, or if the possessive agreement agrees with something other than the “raised” NP: aldjan-na (44) a. *Masha-(qa) beqehee massyyna-m

Masha-(DAT) yesterday car-1sS

‘My car broke down on Masha yesterday.’ break-PAST.3sS b. *Misha-(qa) beqehee at öl-lö.

Misha-dat yesterday horse die-past.3

‘The horse died on Misha yesterday.’

Hence, there must at minimum be some kind of binding/chain formation relationship between the “raised” NP and the syntactic possessor of the theme for the construction to be interpretable. We tentatively assume that it is a movement relationship, although this is not absolutely crucial to our analysis.

Why does the raised possessor get nominative case in some sentences and dative case in others? Pursuing the idea that these are instances of structural case, it must be because the structures of (42) and (43) are slightly different. In fact, our rule of dative case assignment in (2a) tells us what the difference must be. Structural dative case is assigned to an NP only if that NP is inside VP, and there is another NP inside VP that it c-commands. We thus conjecture that the landing sights of the two types of possessor raising are slightly different. In one case, the possessor raises to a position that is high in

VP but still fully contained in VP—such as Spec, VP (or perhaps Spec, ApplP). In the other case, the possessor raises higher, out of the VP phase all together. The two structures are compared in (45).

35

(45) a. [

TP

Misha i

Adverb1 [

VP

Adverb2 [

DP

t i

[

NP

horse] D+AGR ] die ] PAST]

--

Phase 2 Phase 1 b. [

TP

Adverb1 [

VP

Misha i

Adverb2 [

DP

t i

[

VP

horse] D+AGR ] die ] PST]

DAT

Phase 2 Phase 1

In (45b), Misha receives dative case on the VP phase, because it is contained in that phase and c-commands the theme NP, which is also in that phase. In contrast, there is only one NP in the VP phase in the (45a) structure, so dative case assignment does not apply. Moreover, the theme object cannot undergo object shift in this construction (it must be adjacent to the verb, not separated from it by an adverb). As a result, there is only one NP in the CP phase as well—the raised possessor—and accusative case is not assigned either. These structures would thus give as the different case patterns that we observe in (42) and (43), using only our well-established rules of case assignment.

If (45) is correct, we might be able to confirm that there is a structural difference between the two kinds of possessor raising constructions through careful use of adverbs.

Both sorts of possessor raising should cross over adverbs properly contained in VP; these are important for showing that the possessor has raised out of DP in the first place. But there might also be a class of adverbs—adverbs generated in TP or some other constituent larger than VP—which reveal a different. The prediction would be that the nominative-type possessor raising should cross these adverbs more easily than the dative type possessor raising, because the nominative type targets a crucially higher position. In fact, there are data that confirm this. Both types of possessor raising can cross manner

36

adverbs like ‘suddenly’, but nominative possessor raising is more comfortable than dative possessor raising when crossing time adverbs like ‘yesterday’, as shown in (46).

(46) a. beqehee Masha/Masha-qa emiske massyyna-ta aldjanna yesterday Masha/Masha-DAT suddenly car-3s break.

Yesterday Masha’s car suddenly broke on her. b. Masha/??Masha-qa beqehee emiske massyyna-ta aldjanna

Masha/??Masha-DAT yesterday suddenly car-3s break.

Yesterday Masha’s car suddenly broke on her.

Similarly, a nominative raised possessor is more comfortable than a dative raised possessor in front of a modal adverb like ‘probably’:

(47) Masha/??Masha-qa baqar massyyna-ta aldjan-ya

Masha/??Masha-DAT probably

Masha’s car will probably break. car-3s break-FUT.3sS

See also Vinokurova 2005:xx, where it is observed that nominative possessor raising can cross a locative adjunct bearing dative case, but dative possessor raising cannot. It should be noted that the examples with dative raised possessors in front of high adverbs are not entirely out, nor should we expect them to be; there is always the possibility of additional scrambling and focus movement that would move the dative NP from its case position in

(45b). But abstracting away from this, the difference between nominative possessor raising and dative possessor raising seems clear, and goes in the predicted direction. The dative possessor raising construction in particular is it is another example of structural dative case assignment, also attributable to the rule in (2a).

3.7 Case assignment in PPs

37

Finally, we consider an interesting alternation in the kind of case found in certain PPs in

Sakha. The class of postpositions is a rather heterogeneous one in Sakha. Many things that would be expressed by PPs in other languages are expressed either by oblique cases or by “auxiliary nouns”. Moreover, some of the Ps that there are are derived historically either from locative nouns or from participial verbs. Given this, it is not surprising that the case assigning properties of Ps are also rather heterogeneous. We assume that most of them are simply lexically specified as assigning one particular inherent case; for some of them, it is genitive ( kurkuk , like; tuxary , during; nöNüö

, through); for others, dative

( dieri , until; dyly ‘like’); for others, ablative ( taxsa ‘over, beyond; syltaan , because of); for others, accusative ( Byha

‘during’, kytta

‘with’ and nöŋüö ‘over’). We take this to be of no particular interest for our investigation into structural case.

There are, however, three postpositions whose objects undergo an alternation.

The objects of these Ps can be marked with accusative case, or with genitive case:

(48) a. Tyan-(ny) kurdat djie köst-ör. appear-AOR forest-ACC through house

‘A house appears through the forest.’ b. Masha djie-(ni) tula türgennik süür-de quickly run-PAST.3 Misha house-ACC around

‘Misha ran quickly around the house.’ c. Masha tünnük-(ü) utary olor-do sit-PAST.3 Masha window-ACC opposite

‘Masha sat opposite the window.’

38

We claim that when these PP objects bear accusative case, this is the result of structural accusative case being assigned in accordance with rule (6b). The crucial evidence for this is what happens when PPs headed by these Ps modify impersonal verbs that have no thematic subject. When this happens, their complement cannot have accusative case:

(49) a. Ambaar-(*y) tula itii. barn-ACC around hot

‘It is hot around the barn.’ b. Tünnük-(*ü) utary tymnyy. window-acc opposite cold

‘It is cold opposite the window.’

This somewhat peculiar fact can be made to follow on the case competition approach. In

(48) there is another NP argument of the verb which can function as the case competitor for the object of P, licensing accusative, whereas in (49) there is not. The contrast between (48) and (49) is strongly reminiscent of the contrast between raising a subject into a matrix clause that has its own subject ((xx)) as compared to raising a subject into a matrix clause with a subjectless impersonal predicate ((xx)). And like those sentences, the contrast between (48) and (49) gives strong support for the case competition theory.

To flesh out the account, something should be said about the fact that accusative marking is optional in the examples in (48). What does this depend on? Interestingly, the factors that condition this optionality are not the same as those that determine whether the direct object of the verb is accusative or not. It does not have to do with the definiteness of the object: even in a sentence like ‘Misha sat opposite Masha’, accusative is optional on the proper name object, whereas accusative case is required on a proper name serving

39

as the direct object of a verb. Nor is the optionality related to the position of the PP with respect to adverbs: the PP can come before or after an adverb, and accusative case marking on the object is optional in both orders (I house-(ACC) around quickly ran; I quickly house(ACC) around ran). We tentatively assume that the PP as a whole is always generated outside the VP phase. The optionality of accusative case assignment then has to do, we suggest, with the phase status of the PP itself. We claim that these particular P heads optionally count as phases.

11 When the PP is a phase, its object is in a different phase from the subject of the clause, so the accusative case marking rule does not apply; the object either remains unmarked or gets lexical (genitive) case from P. When the PP is not a phase, the object of the P is visible on the matrix CP phase. If the matrix CP contains another NP, as in (48), then accusative case is assigned to the object of P by

(2b). If, however, the matrix CP does not contain another DP, as in (49), accusative case marking does not apply. This accounts for the observed range of facts. Once again the number of NPs in the clause proves to be crucial, as predicted by the configurational account, whereas exactly which functional heads are present is not particularly crucial.

4. Nominative and Genitive: the relationship to agreement

So far, we have considered accusative and dative case in some detail, arguing that they are assigned by configurational rules rather by functional categories. Now we turn to nominative and genitive case in Sakha, to see how they are assigned.

If one’s only goal was to account for the distribution of case suffixes on NPs in

Sakha, it would be easy to extend the configurational account of case assignment to nominative and genitive NPs. It is not hard to formulate rules like those in (2) for these

40

cases; indeed, those rules would essentially be just the complements of the rules that we already have. For example, we could say that genitive case is assigned to the highest NP in a DP phase, otherwise nominative case is assigned to the highest NP in any phase (this rule will be blocked by the more specific rules of dative and genitive assignment; cf.

Marantz 1991). An alternative, more radical but potentially more insightful approach could be to say that there really is no nominative or genitive case in Sakha; what we call nominative and genitive NPs are simply those NPs which are not assigned dative or accusative case by the rules in (2). This could account for both the default nature of these cases in Sakha (they are used wherever no other case is called for) and the fact that these cases are (usually) not marked by any overt morphological exponent. Some refinements might be needed, but we see no reason why a purely configurational approach along these lines could not be made to work.

Case marking does not exist in isolation, however; there are also related morphosyntactic phenomena, such as agreement. The true theory of case should not only explain case marking itself, but also its interaction with as agreement. Indeed,

Chomsky’s (2000, 2001) approach is precisely intended to account for the close relationship between case and agreement that exists in many languages, by claiming that case and agreement are two sides of the same coin; both are reflexes of establishing an abstract relationship (Agree) between a functional head that is missing phi-features and an NP that is missing case features. Capturing the close relationship between case and agreement is not an issue for accusative and dative marked objects in Sakha, because there is no agreement with objects in this language. But the issue does arise for nominative and genitive “subjects”, because these are agreed with in Sakha. More

41

specifically, nominative (unmarked) subjects agree with Tense suffixed to the verb, as seen in the examples throughout this paper, whereas genitive possessor agree with D suffixed to the possessed noun, as shown in (50) (Vinokurova 2005:133).

(50) min oloppoh-um; en oloppoh-u ŋ ; kini oloppoh-o, etc.

I chair-1sP you chair-2sP s/he chair-3sP

‘my chair; your chair; his/her chair’

Similarly, the nominative or genitive subject of a gerund/nominatization agrees with a D suffixed to the nominalized verb, and the nominative or genitive subject of a relative clause agrees with a D suffixed to the head noun (see (xx) below). In this section, we argue that careful consideration of these case-agreement correspondences shows that the

Chomskian analysis of nominative and genitive case should be adopted.

Another way of stating this is as follows. We know that a linguistic relationship

(Chomsky’s Agree) is established between the subject and T in clausal structures and between the possessor and D in nominal structures (also between the subject and D in complex NPs) because we observe agreement between the NP and the functional head.

The question, then, is whether there is any payoff for thinking of case assignment as the other side of this existing relationship between functional head and NP, the functional head valuing an unspecified case feature of the NP at the same time as the NP values unspecified agreement features on the functional head. If so, then the standard minimalist conception would be supported in this subdomain. We argue that there is such a pay-off, and this justifies the familiar case rules in (51), repeated from (3) above:

(51) a. T values the case of NP as nominative if and only if T Agrees with NP. b. D values the case of NP as genitive if and only if D Agrees with NP.

42

4.1 Overt genitive marking and agreement in relative clauses

First, there is one small corner of Sakha grammar in which one can see the interdependence of overt case and agreement fairly directly. This is in a particular kind of relative clauses. Relative clauses in Sakha must be nonfinite, participial clauses, not fully tensed clauses. The participial verb does not itself agree with the subject of the relative clause, the way that a finite verb would. Instead, agreement with the subject of the relative clause shows up on the D that is suffixed to the head of the relative clause

(see Krause xxx for a crosslinguistic study of this sort of relative clause). (52) gives two examples; notice also that when the subject of the relative clause is a possessed NP, it can be seen to bear overt genitive case (compare section 2).

12

(52) a. Masha aqa-ty-n atyylas-pyt at-a b.

Masha father-3s-GEN buy-PAST.PTPL horse-3sP

‘The horse that Masha’s father bought’ bihigi sie-bit balyk-pyt we(GEN) eat-past fish-1pP

‘the fish that we ate’

There is, however, no agreement on the head noun with the subject of the relative clause when that subject itself is the extracted constituent, as shown in (53).

(53) at-y atyylas-pyt kyys (*kyyh-a) horse-ACC buy-PAST.PTPL girl

‘the girl who bought the horse’

(*girl-3s)

43

This is a fairly standard kind of “Anti-agreement Effect”: agreement with the subject is suppressed when that subject undergoes wh-movement; see Ouhalla 1993 for an analysis in these terms of related Turkish.

What makes this relevant for our purposes is the fact that agreement with the subject of a relative clause is also suppressed when a proper subpart of the subject is extracted to form the head of the relative clause:

(54) Kergen-e oqo-lor-go kinige-ler-i bier-bit ucuutal-(*a)

Wife-3s child-PL-DAT book-PL-ACC give-PAST teacher-3s

‘the teacher whose wife gave books to the children’

This is also found in Turkish and at least some other AAE-manifesting languages

(Ouhalla 1993, Kornfilt 1997); presumably whatever rules out agreement in (53) should be generalized to rule it out in (54) as well. We do not take a stand here on what this principle should be.

The crucial fact for our purposes is that the subject in a relative clause like

(54) cannot be marked genitive, in contrast with the subject in (52a).

(55) *kergen-i-n oqo-lor-go kinige-ler-i bier-bit ucuutal wife-3s-GEN child-PL-DAT book-PL-ACC give-PAST teacher

‘the teacher whose wife gave books to the children’

We see then that overt genitive case marking in Sakha is impossible in the very same construction in which agreement on D is ruled out. This strongly suggests that genitive case assignment and agreement on D are intimately related, as in the Chomskian view. If genitive case were assigned configurationally to the highest NP in DP in (52a), without regard to whether an Agree relationship is permitted with the head of the DP, then there

44

would be no reason why the same configurational rule should fail to give genitive case to the parallel NP in (55). Furthermore, if we say that genitive case and agreement on D are two sides of the same coin, then it is at least plausible to extend that view to nominative case and agreement on T, given that the agreement processes are parallel.

4.2 Agreement and Overt Case Marking

Another relevant fact about agreement in Sakha is that T and D never agree with an NP that has already been marked accusative or dative NP on that phase or a previous phase.

For T, this condition is especially evident in passives of ditransitive verbs. When the theme object becomes nominative, T can agree with it ((56a)). But when the theme argument is marked accusative, the verb cannot agree with either internal argument, and must show default third singular morphology ((56b)).

(56) a. At-tar Masha-qa ber-ilin-ni-ler

Horse-pl Masha-dat give-pass-past-pl

The horses were given to Masha. b. Oqo-lor-go at-tar-y ber-ilin-ne/*ber-ilin-ni-ler

Child-pl-dat horse-pl-acc give-pass-past.3sg/*give-pass-past-pl

The children were given horses.

This is also seen in passives of monotransitive verbs: if the thematic object is marked with accusative case, it does not agree with T; if it is not marked accusative, it does.

(57) a. Oloppos-tor aldjat-ylyn-ny-lar. chair-PL break-PASS-PAST-PL

‘Chairs were broken.’ b. Oloppos-tor-u aldjat-ylyn-na. (*aldjat-ylyn-ny-lar)

45

chair-PL-ACC break-PASS-PAST.3

‘Chairs were broken.’

Nor can T agree with the dative subject of a verb like ‘need’; rather, it must look past the dative subject and agree with the lower argument, which is not marked for case by (2a,b).

(58) a. Oqo-lor-go

üüt naada-(*lar)

Child-PL-DAT milk need-PL

‘The children need milk.’ b. Masha-qa kinige-ler naada-lar.

Masha-DAT book-PL need-PL

‘Masha needs the books.’

Finally, T cannot agree a raised possessor that has dative case; it can only agree with the uncase-marked NP that the possessor was raised from in examples like (59).

(59) #Oqo-lor-go djie-ler-e umaj-dy-lar.

Child-pl-dat house-pl-3 burn-past-pl

Bad as: ‘The children’s house burnt’, agreement with the possessor

OK only as: ‘The children’s houses burnt’, with agreement with the theme

So T never agrees with an NP that has already been assigned accusative or dative case.

Similar facts hold for D. In a derived nominalization, for example, D can agree with the thematic subject of the verb root:

(60) Masha terilte-ni salaj-yy-ta

Masha company-ACC manage-YY-3s

Masha’s managing the company

46

The agent of such a nominalization can also be left implicit, as in (60), in which case there is no agreement with the agent (at least overtly).

(61) a. Terilte-ni salaj-yy

Company-acc manage-nom

‘management of the company’ b. Oqo-qo em-i bier-ii

Child-DAT medicine-ACC give-YY

‘the giving of medicine to children’

What is not possible is for the agent to be left implicit, while D agrees with the accusative-marked theme or the dative-marked goal, as shown in (62). These examples are grammatical, but only if agreement is construed as being with a pro-dropped agent argument.

13

(62) a. #Terilte-ni salaj-yy-ta

Company-acc manage-nom-3sg

Not: ‘the management of the company’ (OK as ‘his/her management …) b. #oqo-lor-go em-i bier-ii-ler-e

#Child-PL-DAT medicine-ACC give-YY-pl-3

The giving of medicine to children (OK as their giving medicine to children).

One can compare the nominalization of an active verb in which the subject is left implicit with the nominalization of a passive verb, as shown in (63). The two are thematically similar, in that no agent is expressed overtly, but the theme phrase is accusative in (62a) and is not marked with accusative case in (63). Correlated with this difference in case marking is the fact that D agrees with the theme argument in (63) but not in (62a).

47

(63) Terilte-Ø sala(j)-ll-yy-ta

Company-Ø manage-PASS-YY-3s

The company’s being managed

This pattern also true for agentive nominals of the sort discussed in section 3.4: these also can have accusative marked objects, and they can bear an agreeing D, but the

D cannot agree with the accusative object; it could only agree with a possessor:

(64) Terilte-ni salaj-aaccy-(#ta) company-acc manage-ER-3s

Bad as: ‘the manager of the company’; OK as ‘his/her company-manager’

A similar range of facts can be constructed in relative clauses: the D realized on the head of the relative cannot agree with an accusative or dative NP inside the relative clause. For example, when one extracts the object from a dative subject construction, the