6. Dance and Cultural Identity - Utrecht University Repository

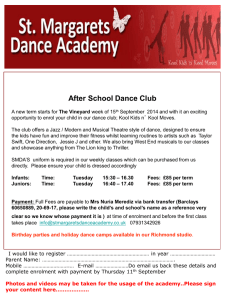

advertisement