religious love interfaces with science

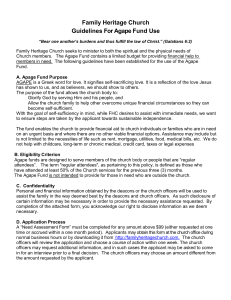

advertisement