Bioinformatics(Biochem 225) Presentation note I

advertisement

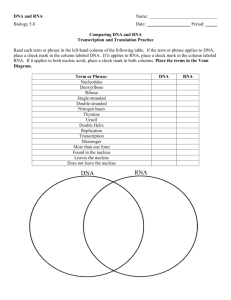

INTRODUCTION TO BIOINFORMATICS Compiled by:- Rajeeb Kumar Singh Lecture 1: Overview of Bioinformatics and Molecular Biology What is Bioinformatics? Defining the terms bioinformatics and computational biology is not necessarily an easy task, as evidenced by multiple definitions available over the web. A recent google search for "definition of bioinformatics" returned over 43,000 results! In the past few years, as the areas have grown, a greater confusion into these two terms has prevailed. For some, the terms bioinformatics and computational biology have become completely interchangeable terms, while for others, there is a great distinction. I'll throw my two cents in, based on what my experience has been to the consensus use of these two terms. Computational biology and bioinformatics are multidisciplinary fields, involving researchers from different areas of specialty, including (but in no means limited to) statistics, computer science, physics, biochemestry, genetics, molecular biology and mathematics. The goal of these two fields is as follows: Bioinformatics: Typically refers to the field concerned with the collection and storage of biological information. All matters concerned with biological databases are considered bioinformatics. Computational biology: Refers to the aspect of developing algorithms and statistical models necessary to analyze biological data through the aid of computers. Understanding of bioinformatics and computational biology follows the NIH definitions listed below: Bioinformatics: Research, development, or application of computational tools and approaches for expanding the use of biological, medical, behavioral or health data, including those to acquire, store, organize, archive, analyze, or visualize such data. Computational Biology: The development and application of data-analytical and theoretical methods, mathematical modeling and computational simulation techniques to the study of biological, behavioral, and social systems. Others have offered various opinions into these definitions as well: http://kbrin.kwing.louisville.edu/~rouchka/definition.html So why is bioinformatics a hot field? One answer to this question is that it is tied to the human genome project which has generated a lot of popular interest. Various advances in molecular biology techniques (such as genome sequencing and microarrays) has led to a large amount of data that needs to be analyzed. Now that we are close to having the human genome finished, what does it all mean? That’s where bioinformatics steps in. Bioinformatics can lead to important discoveries as well as help companies save time and money in the long run. In addition, there needs to be methods to manage large amounts of data. One of the biggest reasons for bioinformatics being a hot field is the old supply and demand adage. There just are too few people adequately trained in both biology and computer science to solve the problems that biologists need to have solved. Image Source: http://ccb.wustl.edu/ . Introduction to Molecular Biology In order to be a good computational biologist, it is important to understand the terminology and basic processes behind the biological problems. Many interesting problems arise out of sequence analysis. There are two different types of biological sequences studied in this class: DNA/RNA and amino acids. But first, let’s make sure the basics are covered. Cells Every organism is made up of tiny structures called cells. Often these cells are too small to be seen with the naked eye. Each cell is in itself a complex system enclosed in a membrane. Some organisms, such as bacteria and baker’s yeast are composed of only a single cell (i.e. they are unicellular). Other organisms are made up of many different cells (i.e. they are multicellular). For instance, the human body is composed of around 60 trillion cells. Humans have about 320 different cell types, each having a different type of function or structural property. There are two types of organisms: eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Eukaryotes (or as Bruce Roe from the University of Oklahoma calls them the “You and I” Karyotes) represent most of the organisms which we can see, including plants and animals. Prokaryotes (such as bacteria) are smaller than eukaryotic cells and have simpler structure. Prokaryotes are single cellular organisms (but not all single-celled organisms are prokaryotes!) So what is the difference between the two types of cells? A eukaryotic cell has a nucleus, which is separated from the rest of the cell by a membrane. Inside the nucleus are the chromosomes, where all of the genetic information for the organism is stored. In addition, eukaryotic cells contain membrane bound organelles with various functions, including centrioles, lysosomes, mitochondria, ribosomes, etc Structure of an animal cell. Contained within the nucleus are one or several long double stranded DNA molecules organized as chromosomes. For humans, there are 22 pairs of autosomes, as well as one pair of sex chromosomes. One copy of each pair is inherited from each parent. Karyotype showing the 23 pairs of human chromosomes. DNA Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) is the basis for the building blocks encoding the information of life. A single stranded DNA molecule, called a polynucleotide or oligomer, is a chain of small molecules called nucleotides. There are four different nucleotides, or bases: adenosine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). The bases can be separated into two different types: purines (A and G) and pyrimidines (C and T). The difference between purines and pyrimidines is in the base structure. Stringing together a simple alphabet of four characters together we can get enough information to create a complex organism! Different nucleotides can be strung together to form a polynucleotide. However, the ends of the polynucleotide are different, meaning that each polynucleotide sequence will have a directionality. The ends of the polynucleotide are marked either 3’ or 5’. The general convention is to label the coding strand from 5’ to 3’ (left to right). For instance, the following is a polynucleotide: 5’ GTAAAGTCCCGTTAGC 3’ DNA can be either single-stranded or double stranded. When DNA is double-stranded, the second strand is referred to as the reverse complement strand. This name is derived from the fact that the directionality of this second strand runs in the opposite direction as the first, and the fact that the bases in the second strand are complementary to the bases in the first. Complementary bases are determined by which pairs of nucleotides can form bonds between them. In the case of DNA, A binds to T, and C binds to G. For the polynucleotide given above, the double-stranded polynucleotide is as follows: 5’ GTAAAGTCCCGTTAGC 3’ | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 3’ CATTTCAGGGCAATCG 5’ | Two complementary polynucleotide chains form a stable structure known as the DNA double helix. This spring represents the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA by Watson, Crick and Franklin. DNA double helix structure. Note that in this image, there appear to be two types of grooves: A larger one, which is called the major groove and a smaller one, known as the minor groove. In addition, there are roughly 10.5 base pairs in one complete turn of the helix. RNA Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) is similar to DNA in the fact that it is constructed from nucleotides. However, instead of thymine (T), an alternative base uracil (U) is found in RNA. RNA can be found as double-stranded or singlestranded, and can also be part of a hybrid helix where one strand is an RNA strand and the other is a DNA strand. RNA is generally found as a single stranded molecule that may form a secondary structure or tertiary structures due to the complementary bases between parts of the same strand. RNA folding will be discussed in detail during a later class period. RNA is important in the cell and contributes in a variety of ways. One of the most important roles of RNA is in protein synthesis. Two of the major RNA molecules involved in protein synthesis are messenger RNA (mRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA). mRNA mRNA encodes the genetic information as copied from the DNA molecules. Transcription is the process in which DNA is copied into an RNA molecule. The resulting linear molecule is an mRNA transcript. In eukaryotic cells, before the mRNA can be translated into a protein, it needs to be modified. The nature of most eukaryotic genes is that the genes are created in pieces, where coding regions, called exons, are interspersed with noncoding regions, called introns. One of the steps in processing the mRNA is to remove the intronic regions and to splice together the coding, or exonic regions. The processed mRNA can then be transported from the nucleus and translated into a protein sequence. tRNA tRNA molecules develop a well-defined three-dimensional structure which is critical in the creation of proteins. Attached to each tRNA molecule is an amino acid (which will be discussed momentarily). The amino acid to be attached is determined by a three base sequence called an anticodon sequence, which is complementary to the sequence in the mRNA. Translation is the process in which the nucleotide base sequence of the processed mRNA is used to order and join the amino acids into a protein with the help of ribosomes and tRNA. Secondary structure for E. coli Rnase P RNA. mRNA processing. tRNA secondary structure. tRNA tertiary structure. Genetic Code Since there are 4 possible bases (A, C, G, U) and 3 bases in the codon, there are 4 * 4 * 4 = 64 possible codon sequences. However, the codon AUG can also be used as a signal to initiate translation, while the codons UAA, UAG, and UGA are terminal codons signaling the end of translation. That leaves a 61 codon sequences that can code for amino acids (AUG can also code for an amino acid). However, there are only 20 amino acids. Therefore the genetic code is redundant, meaning that a single amino acid could be coded for by several different codons. Genetic Code. Note that the initiator codon is labeled in green, and the terminal codons are labeled in red. The first column gives the triplet base; the second the three letter amino acid label, and the third the one letter amino acid label. Second Position of Codon U F i r s t P C o s i t i o n A U C A UUU Phe [F] UCU Ser [S] UUC Phe [F] UCC Ser [S] UUA Leu [L] UCA Ser [S] UUG Leu [L] UCG Ser [S] UAG STOP UGG Trp [W] CUU Leu [L] CCU Pro [P] CAU His [H] CGU Arg [R] CUC Leu [L] CCC Pro [P] CAC His [H] CGC Arg [R] U CUA Leu [L] CCA Pro [P] CAA Gln [Q] CGA Arg [R] A CUG Leu [L] CCG Pro [P] CAG Gln [Q] CGG Arg [R] AUU Ile [I] ACU Thr [T] AAU Asn [N] AGU Ser [S] AUC Ile [I] ACC Thr [T] AAC Asn [N] AGC Ser [S] U AUA Ile [I] ACA Thr [T] AAA Lys [K] AGA Arg [R] A AUG Met [M] ACG Thr [T] AAG Lys [K] AGG Arg [R] UAU Tyr [Y] UAC Tyr [Y] UAA STOP G UGU Cys [C] UGC Cys [C] UGA STOP U C A G C G C G T h i r d P o s i t i o n G GUU Val [V] GCU Ala [A] GAU Asp [D] GGU Gly [G] GUC Val [V] GCC Ala [A] GAC Asp [D] GGC Gly [G] U GUA Val [V] GCA Ala [A] GAA Glu [E] GGA Gly [G] A GUG Val [V] GCG Ala [A] GAG Glu [E] GGG Gly [G] C G Amino Acids Amino acids are the building blocks from which proteins are made. There are 20 different amino acids that vary from each other by their side chain groups. Amino acids can be classified into different groups based on their solubility in water. Hydrophilic amino acids are water soluable, while hydrophobic are not. This property becomes important when a protein sequence is made. Amino acids are linked to one another via a single chemical bond, called a peptide bond. A linear chain of amino acids can be referred to as a peptide (if it is short – less than 30 a.a. long) or polypeptide (which can be upwards of 4000 residues long). One-letter Three-letter G GLY A ALA V VAL L LEU I ILE F PHE P PRO S SER T THR C CYS M MET W TRP Y TYR N ASN Q GLN D ASP E GLU K LYS R ARG H HIS Amino Acid Codes. Proteins Full name Glycine Alanine Valine Leucine Isoleucine Phenylalanine Proline Serine Threonine Cysteine Methionine Tryptophan Tyrosine Asparagine Glutamine Aspartic acid Glutamic acid Lysine Arginine Histidine Proteins are polypeptides that have a three dimensional structure. They can be described through four different hierarchical levels: Primary structure – the sequence of amino acids constituting the polypeptide chain. Secondary structure – the local organization of the parts of the polypeptide chain into secondary structures such as helices and sheets. Tertiary structure – the three dimensional arrangements of the amino acids as they react to one another due to the polarity and resulting interactions between their side chains. Quaternary structure – if a protein consists of several protein subunits held together, then the protein can be described as well by the number and relative positions of the subunits. Visualization of Protein Structures. Magenta: alpha helix Gold: Beta Sheets Blue: Monomer A Orange: Monomer B Calculating the secondary and tertiary structure of a protein given its primary structure is not an easy task. Protein folding prediction will be covered at some point close to the end of the semester. Monomer – Any small molecule that can be linked with others of the same type to form a polymer. For the purpose of this class, the molecules could be nucleic acids, amino acids, or proteins. Dimer - Two small molecules of the same type linked together. Trimer – Three small molecules of the same type linked together. Oligimer – General term for a short polymer most commonly consisting of nucleic acids or amino acids. Polymer – Any large molecule consisting of multiple identical or similar subunits linked by covalent bonds. Putting it all together, we get the flow of genetic information. That is, DNA directs the synthesis of RNA, and RNA then in turn directs the synthesis of protein. This flow of genetic information from nucleic acids to protein has been called the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology. Central Dogma of Molecular Biology DNA RNA PROTEIN What is a Gene? Aaah, the million dollar question. In short, a gene can be described as the physical and functional unit of heredity that carries information from one generation to the next. A gene can be thought of as the DNA sequence necessary for the synthesis of a functional protein or RNA molecule. Genome, Transcriptome, Proteome Whenever the term genome is used, it typically refers to the chromosomal DNA of an organism, or as far as sequencing is concerned, the heterochromatic regions of the chromosomal DNA. The number of chromosomes and genome size varies quite significantly from one organism to another. An example list of genome sizes is given below. Don’t be fooled by this table that the size of the genome and the number of genes determines the complexity of an organism. In fact, many plant genomes are much greater in size than the human genome! ORGANISM Homo sapiens (Humans) Mus musculus (Mouse) Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit Fly) Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yeast) Zea mays (Corn) CHROMOSOMES 23 GENOME SIZE 3,200,000,000 GENES ~ 30,000 20 2,600,000,000 ~30,000 4 180,000,000 ~18,000 16 14,000,000 ~6,000 10 2,400,000,000 ??? The term transcriptome refers to the complete collection of all possible mRNAs (including splice variants) of an organism. This can be thought of as the regions of an organism’s genome that get transcribed into messenger RNA. In some cases, the transcriptome can be extended to include all transcribed elements, including noncoding RNAs used for structural and regulatory purposes. The term proteome refers to the complete collection of proteins that can be produced by an organism. The proteome can be studied either as a static (sum of all proteins possible) or a dynamic (all proteins found at a specific time point) entity. Molecular Biology Reference Books Lewin, B (1999), Genes VII (published by Oxford University Press) ISBN: 019879276X Lodish et al (1995), Molecular Cell Biology, 3rd edition (published by Scientific American Books, Freeman and Cpy, New York) ISBN 0 7167 2380 8 Gonick, L & Wheelis, M (1991), The Cartoon Guide to Genetics (published by Harper Perrenial, New York) ISBN 0 06 273099 1