Abstract - Economic History Society

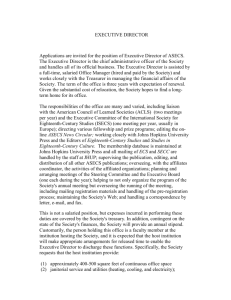

advertisement

“You sacrificed me” : An inter-disciplinary approach to Liverpool’s business culture in the eighteenth-century Atlantic Using ‘networks’ as an analytical tool in economic and business history is very popular at present. However, there is very rarely a real attempt to use the social-science theory from which the term is derived. Other terms being used with equally little care are ‘trust’, ‘risk’, ‘obligation’ and ‘reputation’. This is not to say that borrowing from the ‘neo-institutional economics’ is not useful, but that paying it more than merely lip service could be even more so. Preliminary research has shown that these concepts have relevance for the analysis of eighteenth-century trade. The word concept rather than term is used, because contemporaries thought about ‘networks’ but were more likely to call them ‘associations’ or ‘friends’. They were equally concerned about their reputation, but called it their ‘credit’. It is argued that these concepts are useful for historical analysis, but more attention paid to the theory from which they come would produce a more nuanced analysis and facilitate a more particularised language. Furthermore, they will help to demonstrate how, in a period of minimum regulation, the ‘Atlantic system’ worked so efficiently. This paper will be based on interdisciplinary research funded by an ESRC grant. Using Liverpool’s eighteenth-century Atlantic trade as a case study, it will investigate the concepts of networks, trust, risk, obligation and reputation with two main objectives: to assess how far or often these concepts were considered by contemporaries (even if other terms were used); and how far social-science theory can enlighten these concepts when applied directly to the primary sources. For example, the theory of ‘relational cohesion’ demonstrates how actors in a network often stay in a trading relationship due to past successes, even when more profitable opportunities were presented. 1 Repeated business transactions could lead to the relationship having an affective bond in itself. The notion of ‘impersonal trust’ could help us understand why eighteenth-century merchants took the risk of doing business at extremely long distances with contacts that they only knew by name and/or reputation. 2 Certainly merchants dealt with many people at long distances whom they had never met. Ideas on ‘technological’ versus ‘natural’ risk may enlighten whether merchants thought differently about risk regarding shipping, as opposed to with whom they dealt. 3 For example, a slave ship owner wrote to his Captain to guard against bad decision making for “Misfortunes may to be sure happen that human prudence cannot forsee or guard against, but many there are that might be prevented by prudence and a proper attention”.4 ‘Mutual obligation’ may explain why some merchants extended their networks further and further; whilst others chose to keep potential future calls for help to a minimum. 5 Finally, but by no means least, reputation, or ‘credit’ was the lynchpin of a successful merchant. For example, having trusted in an Irish trader, McDowell, and the system of bills of exchange in general, Liverpool merchant Thomas Leyland was horrified to find that a bill drawn by him had been dishonoured. He wrote to McDowell that “surely you dont consider the consequences of such amatter and how much it injures my credit”. 6 Edward J. Lawler & Jeongkoo Yoon, “Commitment in Exchange Relations: Test of a Theory of Relational Cohesion”, American Sociological Review, 61, 1 (1996), 89-108. 2 Susan P. Shapiro, “The Social Control of Impersonal Trust”, American Journal of Sociology”, 93, 3 (1987), 623-658. 3 Lee Clarke & James F. Short Jr., “Social Organization and Risk: Some Current Controversies”, Annual Review of Sociology, 19 (1993), 375-399. 4 Clemens & Co. to Capt Speers, 3 Jun 1767, Tuohy Papers, Liverpool Record Office (hereafter LivRO). 5 D. E. Muir & E. A. Weinstein, “The Social Debt: An Investigation of Lower-Class and Middle-Class Norms of Social Obligation”, American Sociological Review, 27, 4 (1962), 532-539. 6 Mark Granovetter, “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness”, American Journal of Sociology, 91, 3 (1985), 481-510; Leyland to McDowell, 29 May 1786, Thomas Leyland Letterbook, LivRO. 1 D:\116098009.doc 1 This paper will investigate these themes in order to study the nature of business culture in the eighteenthcentury Atlantic. It will argue that there was a common business culture held together by a mentalité understood by all traders. Following a brief overview of some of the concepts being investigated by this project, this paper will take a closer look at networks and trust. Social-exchange theory and notions of trust are often ‘modelled’ in the social-science literature, and comparing these to the reality of eighteenth-century sources highlights both the problems and potential of using such theories in historical context. 7 In particular they allow a nuanced analysis of how business culture functioned on a day-to-day basis. For example, trust was central to the commercial code of conduct at the personal, institutional and general level. 8 Breaking this code of conduct was considered extremely bad practise and those who suffered by such actions felt very personally insulted. Thomas Leyland found out that two supposedly unconnected trading associates in Ireland had colluded against him. He wrote to one of them that “I have since discovered you were a Partner with him in all these transactions, and to remove your distresses, at the time, you sacrificed me”.9 It will be argued that this inter-disciplinary approach will help us to understand better the mind and business attitudes of the eighteenth-century merchant, and their success in binding the Atlantic economy together. Sheryllynne Haggerty University of Liverpool Abstract for the Economic History Society Conference 2005 sheryllynne.haggerty@liv.ac.uk word count: 956 inclusive of all titles and footnotes. Shane R, Thye, Michael J. Lovaglia & Barry Markovsky, “Responses to Social Exchange and Social Exclusion in Networks”, Social Forces, 75, 3 (1997), 1031-1047. 8 Oliver E. Williamson, “Calculativeness, Trust, and Economic Organization”, Journal of Law and Economics, 36, 2 (1993), 453-486. 9 Leyland to Tallon, 24 Jun 1786, Thomas Leyland Letterbook. 7 D:\116098009.doc 2