Lecture Notes - The Great Compromise

advertisement

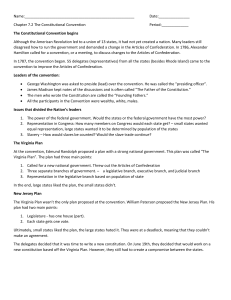

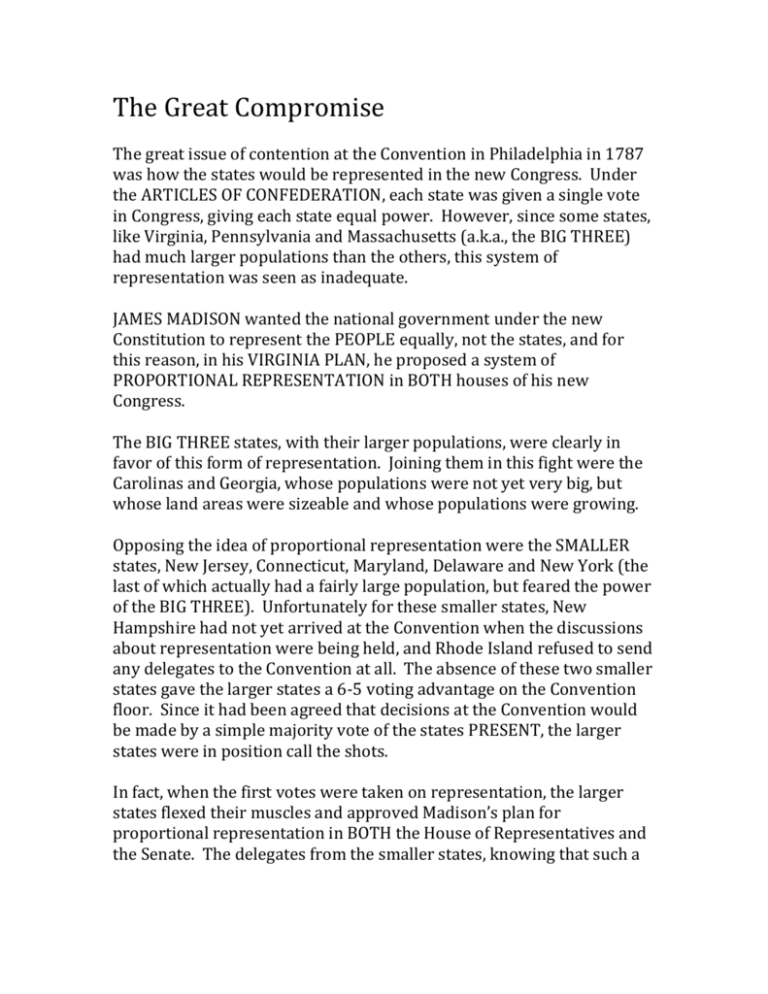

The Great Compromise The great issue of contention at the Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 was how the states would be represented in the new Congress. Under the ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, each state was given a single vote in Congress, giving each state equal power. However, since some states, like Virginia, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts (a.k.a., the BIG THREE) had much larger populations than the others, this system of representation was seen as inadequate. JAMES MADISON wanted the national government under the new Constitution to represent the PEOPLE equally, not the states, and for this reason, in his VIRGINIA PLAN, he proposed a system of PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATION in BOTH houses of his new Congress. The BIG THREE states, with their larger populations, were clearly in favor of this form of representation. Joining them in this fight were the Carolinas and Georgia, whose populations were not yet very big, but whose land areas were sizeable and whose populations were growing. Opposing the idea of proportional representation were the SMALLER states, New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware and New York (the last of which actually had a fairly large population, but feared the power of the BIG THREE). Unfortunately for these smaller states, New Hampshire had not yet arrived at the Convention when the discussions about representation were being held, and Rhode Island refused to send any delegates to the Convention at all. The absence of these two smaller states gave the larger states a 6-5 voting advantage on the Convention floor. Since it had been agreed that decisions at the Convention would be made by a simple majority vote of the states PRESENT, the larger states were in position call the shots. In fact, when the first votes were taken on representation, the larger states flexed their muscles and approved Madison’s plan for proportional representation in BOTH the House of Representatives and the Senate. The delegates from the smaller states, knowing that such a plan would never be approved in their states, asked for one-day’s postponement of the Convention to consider their next move. While some of the smaller state delegates wanted to abandon the Convention at this point, others argued that if the Convention failed to improve our system of government in some substantial way, that the country would fail. The government under the Articles of Confederation was the laughing stock of the civilized world, and was leading the states down the path toward chaos and anarchy. Thus, the smaller state delegates resolved to stay at the Convention and fight to get their opinions heard. WILLIAM PATERSON, a delegate from New Jersey, proposed that the smaller state delegates rally around his newly developed plan for giving the Congress more power (just as Madison had suggested), but doing so while leaving the basic structure of the Confederation Congress intact – meaning a unicameral (one-house) Congress in which each state gets 1 vote and 1 vote only. This plan, known as the NEW JERSEY PLAN, clearly favored the smaller states since they would still have an equal voice with the larger states in a much more powerful Congress. When the Convention reconvened, all of the smaller states rallied around Paterson’s plan. Now the Convention was split pretty much down the middle. The larger states still backed the Virginia Plan with proportional representation, but the smaller states now had the New Jersey Plan, with equal representation for every state, to put up against it. Although the larger states still had a 6-5 voting advantage inside Independence Hall, everyone knew that New Hampshire and Rhode Island (as smaller states) would be much more likely to support the New Jersey Plan when it came time to end the Convention and get the new Constitution ratified by the 13 states. This would likely mean that if proportional representation was adopted at the Convention, the states would likely reject the new Constitution by a 7-6 vote. Clearly neither the Virginia Plan nor the New Jersey Plan was adequate. Each plan favored only one set of interests, and neither would gain the approval of all of the states. Many of the delegates now realized that the time was ripe for COMPROMISE. It just so happened that a delegate from Connecticut, ROGER SHERMAN, had earlier created a compromise plan that would now, in a slightly altered form, become the blueprint for our new legislative branch. Sherman had proposed that the bicameral (two-house) structure of Madison’s Congress be adopted, but with representation in the House based on population (pleasing the larger states) and representation in the Senate based on the 1 vote per state principle that the smaller states preferred. After much contentious discussion and debate, Sherman’s compromise was eventually approved by the delegates at the Convention, with only one slight change: representation in the House would be based on population, while in the Senate, each state would have 2 VOTES instead of only one (a somewhat insignificant change, since the basic principle of each state having equal power was maintained). This compromise is now known as either the GREAT COMPROMISE, or, giving props to Sherman, the CONNECTICUT COMPROMISE. Without this agreement, the Convention likely would have disintegrated in conflict over this single issue of representation. Madison, although he understood its necessity, was not at all happy with the outcome of this compromise. He lamented that the Senate would be a “NON-DEMOCRATIC” body where a state like Rhode Island with a tiny population could cancel out the wishes of a state like Virginia with 20 times the number of people. Even though he thought this was a breach of the fundamental democratic principle that all people should count equally, he eventually came to accept this compromise as the only way that both the large and small states would likely accept the new Constitution.