Overview of preterm labor and delivery

advertisement

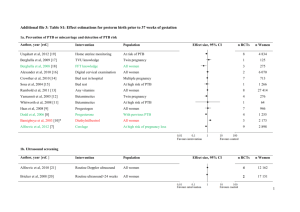

Overview of preterm labor and delivery Author Charles J Lockwood, MD Section Editor Susan M Ramin, MD Deputy Editor Vanessa A Barss, MD Last literature review version 16.1: January 2008 | This topic last updated: April 26, 2007 (More) INTRODUCTION — Preterm birth (PTB) refers to a birth that occurs before 37 completed weeks (less than 259 days) of gestation. A very PTB is more variably defined as less than 32, 33, or 34 weeks of gestation, and an extremely preterm birth is a birth at less than 28 weeks of gestation. SIGNIFICANCE — Taken together with its sequelae, PTB is by far the leading cause of infant mortality in the United States. The relationship between neonatal mortality and gestational age is nonlinear (show figure 1). (See "Perinatal mortality", section on Causes of infant death). PTB is also a major determinant of short- and long-term morbidity in infants and children. (See "Premature infant"). INCIDENCE — In the United States, 12.7 percent of births in 2005 occurred preterm and 2 percent were less than 32 weeks of gestation. (See "Definition; incidence; significance; and demographic characteristics of preterm birth"). PATHOGENESIS — Approximately 70 to 80 percent of PTBs occur spontaneously: preterm labor (PTL) accounts for 40 to 50 percent of all PTBs and preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) accounts for 20 to 30 percent. The remaining 20 to 30 percent of PTBs are due to intervention for maternal or fetal problems (show table 1). Clinical and laboratory evidence suggest that a number of pathogenic processes can lead to a final common pathway that results in preterm labor and delivery. The four primary processes are: Activation of the maternal or fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis Infection Decidual hemorrhage Pathological uterine distention These processes are discussed in detail separately. (See "Pathogenesis of preterm birth"). RISK FACTORS — Numerous risk factors for PTB have been reported (show table 2). A causal association between these risk factors and PTB has been difficult to prove because (1) many PTBs occur among women with no risk factors at all, (2) some obstetrical complications resulting in PTB require cofactors to exert their effect, making the chain of causality difficult to document, and (3) an adequate animal model for study of PTB does not exist. Risk factors for PTB are discussed in detail separately. (See "Risk factors for preterm labor and delivery"). CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS — PTL is one of the most common reasons for hospitalization of pregnant women, but identifying women with preterm contractions who will deliver preterm is an inexact process. In one systematic review, approximately 30 percent of preterm labors spontaneously resolved [1] . Others have reported 50 percent of patients hospitalized for PTL deliver at term [2-4] . Signs and symptoms of early PTL include menstrual-like cramping, constant low back ache, mild uterine contractions at infrequent and/or irregular intervals, and bloody show. However, these signs and symptoms are non-specific and often noted in women whose pregnancies go to term. Uterine contractions, the sine qua non of labor, are a normal finding at all stages of pregnancy, thereby adding to the challenge of distinguishing true from false labor. The frequency of contractions increases with gestational age, the number of fetuses, and at night. Although many investigators have tried, no one has been able to identify a threshold contraction frequency that effectively identifies women who will go on to deliver preterm. The diagnosis of PTL is generally based upon clinical criteria of regular painful uterine contractions accompanied by cervical dilation and/or effacement. Specific criteria, which were initially developed to select subjects in research settings, include persistent uterine contractions (four every 20 minutes or eight every 60 minutes) with documented cervical change or cervical effacement of at least 80 percent, or cervical dilatation greater than 2 cm. Digital cervical examination has limited reproducibility between examiners, especially when changes are not pronounced; therefore, some centers evaluate the cervix via transvaginal ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis [5,6] . Sonographic measurement of cervical length is a more sensitive indicator of a patient's risk for PTB than cervical dilatation. Cervical length is predictive of PTB in all populations studied, including asymptomatic women with prior cone biopsy, mullerian anomalies, or multiple dilation and evacuations [7] . A short cervix has been variously defined as a cervical length less than 2.0 cm, 2.5 cm, or 3.0 cm. The correlation between cervical findings in ultrasound examination and risk of PTB is discussed in detail separately. (See "Prediction of prematurity by transvaginal ultrasound assessment of the cervix"). INITIAL EVALUATION — In addition to reviewing the patient's obstetrical and medical history, the initial evaluation of women with suspected PTL should determine: The presence and frequency of uterine contractions Whether there is uterine bleeding (See "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of placenta previa", see "Clinical features and diagnosis of placental abruption") Whether the fetal membranes have ruptured (See "Preterm premature rupture of membranes") Gestational age (See "Prenatal assessment of gestational age") Fetal well-being (See "Intrapartum fetal heart rate assessment") Uterine contractions and fetal well-being are evaluated using an electronic fetal heart rate and contraction monitor. Physical examination — The uterus is examined to assess firmness, tenderness, fetal size, and fetal position. A sterile speculum examination is performed to rule out ruptured membranes, to visually examine the vagina and cervix, and to obtain specimens for laboratory testing (see below). A digital examination to assess cervical dilatation and effacement is performed after placenta previa and PPROM have been excluded (by history and physical, laboratory, and ultrasound examinations, as indicated). Laboratory tests Urine culture, since bacteriuria and pyelonephritis are associated with PTB. (See "Urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy") Rectovaginal group B streptococcal culture, to determine need for antibiotic prophylaxis. (See "Chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of neonatal group B streptococcal disease") Tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia. Testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia may be omitted if previously performed, the results were negative, and the patient is not at high risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections. Fetal fibronectin (fFN). We obtain a swab for fFN on all patients, but only send the swab to the laboratory if the cervical length is 20 to 30 mm (see "Triage based upon cervical length" below) Given the link between cocaine use and placental abruption, we perform drug testing in patients with risk factors for drug abuse. Imaging — Lastly, we perform an ultrasound examination to measure cervical length. (See "Prediction of prematurity by transvaginal ultrasound assessment of the cervix"). TRIAGE BASED UPON CERVICAL LENGTH — There are no data from large randomized trials to help determine the optimal approach to management of women with suspected PTL and intact membranes. The approach described below reflects our paradigm based upon our experience and data from observational studies (see "Background data" below). Cervical length >30 mm — These women are at low risk of PTB [8,9] , regardless of fFN result, so we do not send their swabs for fFN testing to the laboratory. We discharge the patients home after an observational period of four to six hours during which we confirm fetal well-being (eg, reactive nonstress test), exclude the presence of an acute precipitating event (eg, an abruption or infection), and assure ourselves that the cervix is not dilating or effacing. Follow-up in one to two weeks is arranged and the patient is given instructions to call if she experiences additional signs or symptoms of PTL, or has other pregnancy concerns (eg, bleeding, PROM, decreased fetal activity). (See "Patient information: Preterm labor"). Cervical length 20 to 30 mm — PTB is more likely in women with cervices 20 to 30 mm than in women with longer cervices, but most women in this group do not deliver preterm. Therefore, we send the swab for fFN testing in this subgroup of women. If the test is positive (level greater than 50 ng/mL), we actively manage the pregnancy to prevent morbidity associated with PTB. (See "Prediction of prematurity by transvaginal ultrasound assessment of the cervix"). Cervical length <20 mm — These women are at high risk of PTB regardless of fFN result. Therefore, we do not send their swabs for fFN testing to the laboratory and actively manage them to prevent morbidity associated with PTB. Background data — In women with preterm contractions, sonographic cervical length assessment, followed by fFN if the cervix is short, improves the ability to distinguish between women who will and will not deliver within 7 or 14 days. This was illustrated in a study showing that women with cervical length ≥30 mm were unlikely to deliver preterm and that measuring fFN did not enhance the predictive value of ultrasound examination in these women [10] . By comparison, if the cervix was <30 mm in length, the risk of delivery within seven days with positive and negative fFN results was 45 and 11 percent, respectively; the risk of delivery within 14 days was 56 and 13 percent, respectively. Delivery within seven days occurred in 75 percent of women with cervical length <15 mm and positive fFN. One prospective blinded study concluded that fFN was most useful in symptomatic women with cervical length 16 to 30 mm [11] . In this study, ultrasound cervical length and fFN data were collected in symptomatic patients, but the results were blinded to the physicians. A fFN ≥50 ng/mL was significantly more reliable than an ultrasound cervical length determination ≤25 mm for identifying patients who would deliver preterm. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of cervical length ≤25 mm for PTB were 75, 63, 24, and 94 percent, respectively, while the corresponding figures for fFN ≥50 ng/mL, were 63, 81, 33, and 93 percent, respectively. The authors went on to determine whether selective use of fFN after cervical length measurement could decrease the number of fFN tests ordered. As noted above, women with cervical length >30 mm were unlikely to deliver within seven days and the addition of fFN testing did not significantly improve the predictive value of cervical length measurement alone. Cervical length ≤15 mm or fFN ≥50 ng/mL plus cervical length 16 to 30 mm were predictive of PTD and the sensitivity specificity, and predictive values (67, 81, 36, and 94 percent, respectively) were not significantly different from those of using fFN alone. Limiting fFN testing to women with intermediate cervical length avoided 200 tests in this population. Others have also found that it is possible to use fFN testing selectively. One such study reported that only positive fFN testing and functional canal length <20 mm were independently associated with PTD [12] . The authors proposed two-step testing: first, sonographic assessment of the cervix is performed with functional canal length <20 mm as a positive result and >31 mm as a negative one. fFN testing is then performed only in patients with length 21 to 31 mm. Two-step testing had overall sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of 86, 90, 63, and 97 percent, respectively, for predicting delivery within 28 days. The combined use of the cervical sonography and fFN testing predicted PTD with higher sensitivity and negative predictive value than any of the methods alone. MANAGEMENT OF WOMEN WITH PRETERM LABOR — We hospitalize women diagnosed with PTL at less than 34 weeks of gestation and initiate the following treatments: Antenatal glucocorticoids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with PTB (See "Antenatal use of glucocorticoids in women at risk for preterm delivery"). Appropriate antibiotics for GBS chemoprophylaxis (See "Chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of neonatal group B streptococcal disease"). Tocolytic drugs for 48 hours to delay delivery so that glucocorticoids given to the mother can achieve their maximum effect. (See "Inhibition of acute preterm labor"). Appropriate antibiotics to women with positive urine culture results or positive tests for gonorrhea or chlamydia. (See "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth"). Management of women after diagnosis and initial treatment of PTL is discussed separately. (See "Management of pregnant women after inhibition of preterm labor"). MANAGEMENT OF ASYMPTOMATIC WOMEN AT HIGH RISK OF PTB — Interventions to prevent PTB generally have not been successful, with some exceptions (eg, supplemental progesterone). (See "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth", section on Supplemental progesterone). Women with risk factors for PTB are sometimes followed with serial ultrasound measurement of cervical length. A cervical length ≥35 mm is generally considered normal and reassuring; as cervical length decreases below 35 mm, the risk of PTB increases (show table 3). We manage asymptomatic patients at high risk of PTB similar to the way we manage symptomatic patients, but with a higher cervical length threshold for intervention. This minimizes overtreatment of high risk asymptomatic patients and undertreatment of symptomatic patients. Surveillance with serial cervical length measurements is begun at 22 weeks. Cervical length ≥35 mm - The risk of PTB is low. We see these patients in routine follow-up in one to two weeks. Cervical length 25 to 34 mm - We obtain a fFN concentration. If the test is positive (level greater than 50 ng/mL), we actively manage the pregnancy to prevent morbidity associated with PTB. As an example, we consider administering a course of glucocorticoids, we suggest that the patient stop physically demanding work, and we give appropriate antibiotics to women with positive urine culture results or positive tests for gonorrhea, chlamydia, or bacterial vaginosis. Early aggressive treatment of bacterial vaginosis in high risk patients may reduce PTB/PPROM [13,14] . (See "Bacterial vaginosis", section on Treatment in pregnancy). Cervical length <25 mm - The risk of PTB is increased. We actively manage the pregnancy to prevent morbidity associated with PTB, as described above. INFORMATION FOR PATIENTS — Educational materials on this topic are available for patients. (See "Patient information: Preterm labor"). We encourage you to print or e-mail this topic review, or to refer patients to our public web site, www.uptodate.com/patients, which includes this and other topics. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS The diagnosis of preterm labor (PTL) is based on clinical criteria of regular painful uterine contractions accompanied by cervical dilation and/or effacement. Ultrasound measurement of cervical length and laboratory analysis of cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN) level can help to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of preterm labor (see "Clinical manifestations and diagnosis" above). We suggest cervical length measurement be used to identify patients for further evaluation and therapy (Grade 2C) (see "Initial evaluation" above and see "Triage based upon cervical length" above). We suggest treatment of women with suspected PTL (Grade 2C). We administer tocolytic drugs; appropriate antibiotics to women with positive urine culture results or positive tests for gonorrhea, and chlamydia; appropriate antibiotics for GBS chemoprophylaxis, and antenatal glucocorticoids to reduce neonatal morbidity and mortality associated with preterm birth (see "Management of women with preterm labor" above). We suggest treatment of asymptomatic women at high risk of preterm birth be based upon cervical length measurement and fFN results (Grade 2C) (see "Management of asymptomatic women at high risk of PTB" above).