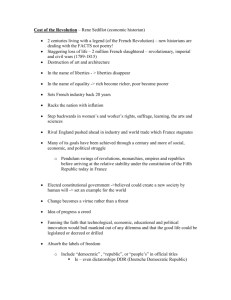

Levee en Masse

advertisement

Levee en Masse Levee en masse literally means “mass uprising”. It is a French term for the mass conscription during the Revolution. The term Levee en masse denotes a short-term requisition of all able-bodied men to defend the nation and was based upon the concept of the democratic citizen versus the royal subject. Central to the understanding of the Levee is the idea that the new political rights given to the mass of French people also created an obligation to the state. As the nation now understood itself as a community of ALL people, its defense also was assumed to become the responsibility of ALL. Thus, the levee en masse was created and understood as a means to defend the nation for the nation by the nation. It heralded the age of the people’s war and displaced prior restricted forms of warfare as the cabinet wars when armies of professional soldiers fought without general participation of the population. From this point on, war was to become “total” involving all elements of the population and all the reserves of the state. The levee en masse was born in the French Revolution. Under the Old Regime, there had been conscription by ballot to a militia to supplement the large standing army in times of war. This had been unpopular with the peasants on who this fell, and it was one of the main grievances the peasants brought to the Meeting of the Estates-General. This type of conscription was then abolished by the National Assembly. As the Revolution progressed, external enemies appeared to invade France to restore the French monarchy. They were resisted by a mixture of what remained of the old professional army and volunteers like at the Battle of Valmy. By March 1793, France was at war with Austria, Prussia, Spain, Britain, Belgium, Piedmont, and the Netherlands. The government realized they could no longer rely on volunteers to supplement the army. The National Convention called upon each French department to supply a quota of recruits totaling about 300,000. By some accounts, only half this number appears to have been actually raised, bringing the army strength up to about 650,000 in mid-1793. Due to this, the military situation for France worsened. In response to this, a levee en masse was decreed by the National Convention on August 23, 1793: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. From this moment until that in which the enemy shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the service of the armies. The young men shall go to battle; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothing and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen into lint; the aged shall betake themselves to the public places in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach the hatred of kings and unity of the Republic. The national buildings shall be converted into barracks, the public places into workshops for arms, the soil of the cellars shall be washed in order to extract therefrom the saltpeter. The arms of the regulation caliber shall be reserved exclusively for those who shall march against the enemy; the service of the interior shall be performed with hunting pieces and side arms. The saddle horses are put into requisition to complete the cavalry corps the draft horses, other than those employed in agriculture, shall convey the artillery and the provisions. The Committee of Public Safety is charged to take all necessary measures to set up without delay an extraordinary manufacture of arms of every sort which corresponds with ardor and energy of the French people. It is, accordingly, authorized to form all the establishments, factories, workshops, and mills which shall be deemed necessary for the carrying on of these works, as well as to put in requisition, within the entire extent of the Republic, the artists and workingmen who can contribute to their success. The representatives of the people sent out for the execution of the present law shall have the same authority in their respective districts, acting in concert with the Committee of Public Safety; they are invested with the unlimited powers assigned to the representatives of the people in the armies. 7. Nobody can get himself replaced in the service for which he shall have been requisitioned. The public functionaries shall remain at their posts.” As a result of this decree, all single men between the ages of 18 and 25 were required to join the army. The French population at the time was the second largest in Europe, only beat by the Russians. Thus, it had the people to support a huge military mobilization. By September 1794, the French Republic had 1, 169,000 men under arms out of a total 25 million people. The percentage of population mobilized during the French Revolution was unprecedented in Europe and was a revolutionary achievement. Therefore, the first meaning of the word referred to literally the goal of mass mobilization; the provision of the large numbers of soldiers supported by the people. For all his brilliance as a general, Napoleon could not have accomplished his dramatic transformation of the European landscape without the broad-based participation of the French population with the young male conscripts and the civilian labor. Numbers were crucial to the strategy of the French army, enabling it to function on several fronts simultaneously and to sustain the casualities that its opponents could not bear. The French tended to win when they had superiority in numbers. They enabled Napoleon to take greater risks, engage in battle more often, spread his troops over wider territory, and embark on more daring political ends. His opponents soon learned to counter his mass, with the result being a dramatic increase in the average of men engaged in battle in Europe. The resulting mobilization of the people in service of the state foreshadowed the nationalized warfare of the industrialized era in WWI and WWII. For Napoleon, the people were clearly the “engine of war.” This literal meaning of levee en masses as mass conscription is best known. But its second meaning, levee as uprising, is more crucial as it explains the shift in political power from a small minority to the mass majority. The French populace was reached, radicalized, educated, and organized so as to save the revolution and participate in its wars. While this was happening, there was a huge explosion in means of communication with a dramatic growth in journals, pamphlets, newspapers, and other short-lived forms of literature. No popular mobilization could succeed if there was no expanding popular communication. There was no longer censorship of texts. Books were published in shorter form and for less cost. Therefore, more were published. Over the course of the French Revolution, the number of journals produced in Paris alone went from 4 to 335. The number of printers quadrupled, and the number of publishers and sellers nearly tripled. It also started the trend of publishing the lyrics of songs for the masses to encourage unity and a sense of the republican identity. Revolutionary images were also important. Images of the storming of the Bastille flooded newspapers, pamphlets, and engravings. Such powerful symbolic pictures appeared on paper money, letterheads, stamps, membership cards, calendars, wallpaper, and children’s games. Communications was central to developing a national identity, a sense of passion among the people, and motivated the fight for the Revolution. The role of the poor French peasant was central to the power of the army. The passionate participation of the working-class Frenchmen was vital to the organization for war. The French believed that they were fighting a war for freedom and against tyranny. They were fighting for the Revolution and against monarchial power. The French nation and army were one. The levee en masses was the process of physical and ideological mobilization of the masses into war in the service of the French Republic. *The historical information for this reading came from the US Army Professional Writing Collection and Paul Halsall’s Modern History Sourcebook for Fordham University.