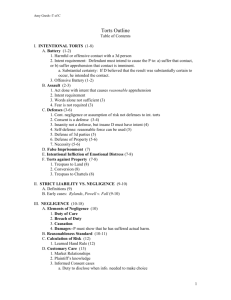

Torts Outline – Maatman

Torts- Maatman Fall 2007

I.

What is a tort? a.

Conduct that amounts to a legal wrong, and causes harm for which courts will impose civil liability. b.

Legal wrong—causes harm—civil liability imposed. c.

Legal: cognizable- something courts “recognize as a legal wrong that justifies compensation. d.

Wrong = fault. Courts look for fault. i.

Fault

1.

Intentional wrongdoing.

2.

Recklessly.

3.

Negligently. e.

Justification for compensation, goals of tort law: i.

Hold wrongdoers accountable. ii.

Restore injured persons to original position. iii.

Deter wrongdoing. iv.

Establish consistent norms.

II.

Four main branches of tort law: a.

Intentional. b.

Negligence. c.

Strict Liability (no fault). d.

Economic and Dignitary.

III.

Intentional Torts (6 C.O.A., 1 defense). a.

Battery. b.

Assault. c.

False Imprisonment. d.

Trespass to land. e.

Trespass to chattels. f.

Conversion. g.

Affirmative defends (D asserts).

IV.

Intent a.

General: Intent to bring about a harmful or offensive contact is determined by: i.

Acting for the purpose of causing contact, or ii.

With substantial certainty that such conduct will occur. (Garratt) b.

Transferred (Hall): i.

A tortfeasor intends a tort on one person, but commits a tort on another.

1.

Ex: Intent to commit battery on one person but batters another. ii.

A tortfeasor intends one tort, but accomplishes another.

1.

Ex: Intend assault but actually commits battery. c.

Insane/mentally deficient persons: i.

May be held liable for their torts, can form the necessary intent regardless of the rationality of their motives for that intent. (Polmatier) ii.

Dual intent required- actor must have intended offensive or harmful consequences (White).

iii.

Insanity, while not a defense, may make the intent element more difficult

V.

BATTERY to prove. (White) a.

Fault (Van Camp) i.

Fault is required for intentional wrongdoing. ii.

The plaintiff must plead all of the elements to sustain a cause of action. b.

Elements (Snyder) i.

Battery: Acting with the intent to cause a harmful or offensive contact, and when that contact results. ii.

Single Intent: intent to cause contact only (minority) iii.

Dual intent: intent to cause contact and intent that it be harmful or offensive, contact must always result (majority) iv.

Offensive contact: Offensive to a reasonable sense of personal dignity.

1.

“Offensive” is defined as disagreeable, nauseating or painful because of outrage to taste and sensibilities or affronting insultingness. (Leichtman) a.

Ex: Kiss, blowing smoke, throwing water on someone.

2.

“Reasonable” is what is accepted as mainstream or by society. v.

Even seemingly trivial batteries are actionable. vi.

There is no “smoker’s battery.” Contact must be intentional, not circumstantial. vii.

Defendant can be liable for unforeseen consequences of a battery.

VI.

ASSAULT a.

Elements: i.

Assault: Acts intending to cause a harmful or offensive contact with the person of the other, or an imminent apprehension of such contact.

1.

Apprehension a.

Normally aroused in mind of reasonable person. b.

Awareness, anticipation.

2.

Imminent: a.

Without significant delay. ii.

The right to be free from imminent apprehension of battery is protected by the tort of assault. (Cullison) iii.

There must be an apprehension of an immediate battery to sustain an assault claim. (Kofman) iv.

Words Alone Rule: Words are not sufficient to constitute an assault; they must be accompanied by some overt act that adds to the threatening character of the words. v.

Transferred intent applies. vi.

Conditional threats and emotional distress can constitute assaults.

VII.

FALSE IMPRISONMENT a.

Elements: (McCann)

i.

Conduct which is intended to, and does in fact confine another within boundaries fixed by the actor for any appreciable time, and ii.

The victim is either conscious of the confinement or harmed by it. b.

Confinement can be based on: i.

Imposition of physical barriers/force. ii.

Threats of physical force, implicit and explicit. iii.

False assertion of legal authority to confine. iv.

Other unspecified means of duress.

VIII.

TRESPASS TO LAND a.

Intentional entry upon the land of another. i.

Entry: personal entry or causing an object to enter the land. ii.

Intent:

1.

Intent to enter land, even if you don’t know it isn’t yours.

2.

Intentional entry not needed if you enter unintentionally and refuse to leave after a reasonable time. iii.

No liability imposed for accidental entries that aren’t negligent. b.

Damages: i.

Liability even without physical or economic harm. ii.

Punitive damages allowed if entry is deliberate or malicious, no harm required. iii.

Extended liability also allowed.

IX.

CONVERSION OF CHATTELS a.

Intentional deprivation of property from the rightful owner by exercising the rights of an owner over the property of another. Must exercise substantial dominion and control over property. b.

Defendant need not be conscious of wrongdoing. Exercise of dominion and control is all that matters. c.

Only personal property may be converted. d.

Damages: value of chattel at time of conversion or replevin.

X.

TRESPASS TO CHATTELS a.

Intentional intermeddling with a chattel of another person, even dispossession, but something short of a conversion. i.

Intermeddling is defined as intentionally bringing about a physical contact with the chattel. (CompuServe) b.

Liability is imposed only if the possessor of the chattel suffers dispossession, lost use, if the chattel is impaired as to its condition, quality, or value, or if the chattel or the possessor is harmed. c.

Damages: actual damages, not market value. d.

Rule: Electronic signals generated and sent by computer are sufficiently tangible to support a trespass cause of action. (CompuServe)

XI.

AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES a.

Self Defense

i.

A defense to battery, assault, false imprisonment (means). ii.

Definition: Use reasonable force to defend against harmful or offensive contact and/or confinement. Proportionality. iii.

Privilege extends to reasonable force necessary to prevent harm. Deadly force only if harm threatened is death or serious bodily injury.

Proportionality. iv.

No retreat requirement. v.

Privilege does not extent to initial aggressor as long as other party’s use of force is reasonable or proportionate. vi.

Defense of Others: may defend others as they could if defending themselves. No privilege for mistakes. vii.

Use of Deadly Weapons/Force (Slayton v. McDonald)

1.

Generally, one isn’t justified in using a dangerous weapon in selfdefense if the attacking party is not armed but only commits a battery with his fists or in some manner not inherently dangerous to life.

2.

Resort to dangerous weapons to repel an attack may be justifiable where the fear of danger of the person attacked is genuine and founded on facts likely to produce similar emotions in reasonable men.

3.

The reasonableness of actions of the party being attacked require consideration of the character and reputation of the attacker, the belligerence of the attacker, a large difference in size and strength between the parties, overt attack by the attacker, threats of serious bodily harm and the impossibility of a peaceful retreat. b.

Shopkeeper’s Privilege—Arrest and Detention i.

A shopkeeper may detain a suspected shoplifter if:

1.

He reasonably (prob. cause) believes the person has tortiously taken his property, a.

No probable cause exists unless the suspect actually attempts to leave without paying, unless he manifests control over the property in such a way the his intention to steal is unequivocal.

2.

The detention is conducted in a reasonable manner, and

3.

The detention is limited to a reasonable period of time to make an investigation/recover property. ii.

If the person detained does not unlawfully have any of the arrestor’s property, the arrester is liable for false imprisonment. c.

Defense and Repossession of Property i.

An owner of a premise is prohibited from willfully or intentionally injuring a trespasser by means of force that either takes life or inflicts great bodily injury.

1.

The exception is when the intrusion threatens death or serious bodily injury to the occupier or user of the premises. (Katko) ii.

There is no privilege to use any force calculated to cause death or serious bodily injury where only property is threatened. (Brown)

1.

Law places a higher value on human safety than property rights. iii.

The property owner may use the force reasonably necessary to overcome resistance and expel the intruder, and if his own safety is threatened, deadly force is justified. (Brown) d.

Privilege of Consent i.

Defense to all intentional torts. ii.

2 types will extinguish liability

1.

Actual- subjective willingness (from P’s POV) for D’s act to occur.

2.

Apparent conduct (P’s) - includes words reasonably understood by another as consent. iii.

Consent defense precludes recovery for all consequences of the other person’s act that you consented to. iv.

Capacity to Consent:

1.

Adult- must be able to manage own affairs or understand the nature/character of the act.

2.

Minor- can consent to touching appropriate to their age.

3.

No capacity to consent to illegal acts.

4.

There is liability for exceeding scope of consent. v.

Incapacity will make consent ineffective if D has knowledge of the incapacity and a prior condition substantially impairs the ability to weigh harm, risks v. benefits.(Reavis) vi.

Assumption of Risk

1.

Persons who engage in roughhouse horseplay also accept the risk of accidental injuries which result from participation therein.

(Hellreigel) e.

Necessity i.

Public Necessity (Surocco)

1.

The private rights of the individual yield to the interests of general convenience and society.

2.

Necessity justifies destroying private property to prevent the spread of a conflagration and to protect the property and lives of others.

3.

The necessity must be clearly shown. Without apparent or actual necessity, the parties involved would be liable for trespass. ii.

Private Necessity

1.

Personal property may be sacrificed to save your life or the lives of others. (Ploof)

2.

Necessity does not preclude liability for damage done to property while protecting one’s property. You cannot be ejected from one’s property, but you are liable for damage done. (Vincent)

XII.

NEGLIGENCE a.

Definition: i.

Any conduct that creates an unreasonable risk of harm to others.

ii.

Absence of ordinary care which a reasonably prudent person would exercise under the circumstances. Ordinary care is care that RPPSSC would use. iii.

Standard of Proof: By preponderance of the evidence. b.

Elements: i.

Duty ii.

Breach of Duty iii.

Actual Harm iv.

Cause-in-fact (actual cause) v.

Proximate cause (legal cause) c.

Affirmative Defenses: i.

Contributory Negligence ii.

Comparative Negligence iii.

Assumption of the Risk

1.

Express

2.

Implied d.

Variations on a negligence COA i.

Landowner’s duty. ii.

COA’s purely emotional harm (Int. Infl. Emot. Distress). iii.

Duties to protect P from another. iv.

Employer’s liability for employee’s negligence. e.

Duty i.

Whether a duty is owed and the nature of the duty owed. Define duty, define scope of liability. ii.

General Duty: act as a reasonably prudent person acting under the same or similar circumstances (RPPSSC).

1.

This means you must recognize risks that an RPPSSC would, and take steps to avoid/minimize risks.

2.

Fault—not recognizing or failing to avoid/minimize risks.

3.

Reasonableness depends on risk of harm involved and practicability of preventing it. iii.

Negligence SOC:

1.

The only standard of care that applies to negligence actions is reasonable care under the circumstances. This care is proportionate to the danger involved. iv.

Emergency situations:

1.

The test of negligence in emergency situations is the same as that to be applied in other cases: RPPSSC.

2.

Rule: A superfluous emergency instruction is now useless. It tells the jury what is an emergency, rather than leaving it to their discretion. f.

Variations of Duty i.

Children/Minors:

1.

General Rule: Must act as a reasonably prudent child of same and similar age, intelligence, maturity, training, experience.

2.

Exception: When a child is engaging in an activity that is inherently dangerous, the child is held to an adult standard. a.

Inherently dangerous activity: one capable of resulting in grave danger to others or the minor itself, if the standard of care drops below adult standard. b.

Example: motorized vehicles (car, snowmobile, etc)

3.

Rule of Sevens (minority approach) a.

Under 7—conclusively presumed incapable of negligence. b.

7-14—presumed incapable, but this is rebuttable. c.

Over 14—presumed capable of negligence.

4.

Majority Approach: a.

Under 3—Incapable of negligence. ii.

Mental Disabilities:

1.

A person with mental disabilities is generally held to the same standard of care as that of a reasonable person under the same circumstances, without regard to their capacity to control or understand the consequences of his/her actions.

2.

In cases involving one employed to take care of a patient, the duty of care is one-way from the caretaker to the patient. iii.

Physical Disability:

1.

Standard of care is that as an ordinary person with a like infirmity would have exercised under the same or similar circumstances. iv.

Superior Knowledge:

1.

If one has superior knowledge, they are required to exercise that knowledge in a reasonable manner under the circumstances. (SSC part of standard of care) v.

Medical Condition/Emergency:

1.

An operator of a motor vehicle who, while driving, becomes suddenly stricken by a fainting spell or loses consciousness from an unforeseen cause, and is unable to control the vehicle, is not chargeable with negligence or gross negligence.

2.

Fainting or momentary loss of consciousness while driving is a complete defense to negligence if it was not foreseeable. g.

Negligence Per Se (matter of law) i.

Fuses two things:

1.

There is a duty, which is defined by: a.

Court as rule of thumb. b.

Statute.

2.

Breach. ii.

Statute sets standard of care. A violation of the statute is a breach of the standard of care. Thus, duty and breach. iii.

Plaintiff still must establish legal cause, cause-in-fact and damages. iv.

Preliminary Question:

1.

Does a statute specify standard of care, more specific than general duty? v.

Two-Step Test:

1.

Is plaintiff in class to be protected by statute?

2.

Is the harm of the type the statute was designed to prevent? vi.

An excused violation of a legislative enactment is not negligence. Five categories of excusable situations:

1.

Incapacity: age, mental capacity, physical disability/incapability.

2.

Ignorance: no awareness of violation of law (light out on car)

3.

Inability: impossible to comply after due diligence/care.

4.

Emergency: not due to own misconduct (tire blowout)

5.

Greater risk of harm to actor or others w/ compliance. vii.

A minor’s violation of a statute is not negligence per se. It can be used h.

Breach only as evidence of negligence. i.

Notes

1.

Usually a jury question. Was conduct at issue unreasonably risky?

2.

If a judge believes no reasonable jury could find for P, breach question doesn’t go to the jury.

3.

Inquiry in breach analysis relies on either an implicit or explicit cost-benefit analysis.

4.

Conduct is always viewed through lens of foreseeability. For breach, harm must be foreseeable and too likely to occur to justify risking harm without adequate precautions.

5.

Harm must be more than possible to be reasonably foreseeable.

The harm must be objectively expected to occur. ii.

Undue Risk, Absence of reasonable care = Breach

1.

Taking some risk isn’t breach. Only an undue risk is a breach of duty. Standard is RPPSSC. (Mathew) iii.

Breach by employer:

1.

A reasonably prudent employer has a duty to furnish a reasonably safe workplace and tools, regarding the character of the work.

RPESSC. However, if an employee’s knowledge of job is equal or better than employer’s, the employee has a responsibility too.

Thus, the employer isn’t liable. (Stinnett) iv.

Cost-Benefit Analysis Tests

1.

Implicit Cost Benefit Analysis: a.

There is a duty to take precautions against pole knockdowns by cars. The designer and controller of the pole must anticipate the environment in which it will be used, and must design against reasonably foreseeable risks in that environment. (Bernier) b.

Degree of risk of harm must be weighed against the privilege to protect property. Recovery of property as a matter of law does not expose invitees to an unreasonable risk of harm. (Giant)

2.

Explicit Cost Benefit Analysis: a.

Hand formula: Probability v. burden of adequate protection determines breach. (Carroll Towing)

i.

If Burden < Probability x Loss, then breach. ii.

If B> PxL, then no breach. v.

Proving Conduct

1.

Inferences must be more than speculation. a.

No info on accident, only a speculative inference.

(Santiago) b.

Inferences can be drawn from physical evidence w/o actual eyewitness testimony. (Upchurch) vi.

Evaluating Conduct

1.

Slip & Fall Cases a.

To recover, P must show that: i.

D created a dangerous condition, or ii.

had actual or constructive knowledge of a dangerous condition. b.

Notice of dangerous condition may be established by circumstantial evidence, such as evidence leading to an inference that a substance has been on the floor for a sufficient length of time such that, in the exercise of reasonable care, the condition should have become known to the premises owner.

2.

Safety Manuals a.

The failure of a party to follow its own precautionary steps or procedures is not necessarily failure to exercise ordinary care. These steps/procedures are merely evidentiary and are not a legal standard of care. (Wright)

3.

Custom & General Use a.

Evidence of custom and general use is admissible because it can establish a standard by which ordinary care can be judged. Custom can prove harm was foreseeable, that D knew or should have known risks, the risk was unreasonable unless customary precautions taken. (Duncan) b.

Reasonable men can recognize that what is usually done may be evidence of what should be done. (McComish) c.

There are precautions so imperative that even their universal disregard will not excuse their omission. (TJ

Hooper) i.

Res Ipsa Loquitur - “the thing speaks for itself” i.

Specialized shortcut to prove a breach, for things that don’t normally happen without negligence. ii.

Effects:

1.

Avoids directed verdict, nonsuit.

2.

Gets case to the jury with instruction that permits, but not requires, it to find D negligent. iii.

Two threshold questions before res ipsa:

1.

Is there a complete explanation?

a.

This is the difference between knowing what happened and guessing what happened. Possible explanation isn’t complete. b.

If yes, no RIL.

2.

Superior Knowledge. a.

RIL not applicable only if P has superior knowledge. b.

If both P and D have it, RIL ok. Equality of ignorance. iv.

Elements: It may be inferred that P’s harm is caused by D’s negligence if:

1.

The event would not normally occur without negligence.

2.

The instrumentality or agent causing accident is under D’s control. a.

Exclusive control not required. b.

D must have right or power of control, and the opportunity to exercise it (Giles). c.

D’s control must be enough to show that D was more likely responsible than someone else (Giles). d.

RIL ok for more than one defendant if they had consecutive control over the P. (Collins).

3.

The event wasn’t caused by others or plaintiff’s acts, negligence.

Other causes substantially eliminated. v.

R: RIL not blocked if it is impossible to prove P didn’t contribute to cause of accident. P no prove negative. j.

Actual Harm i.

P needs to suffer Cognizable Harm/Damages:

1.

Past and future medical expenses.

2.

Loss of wages or earning capacity.

3.

Pain and suffering, including emotional harm (not same as emotional loss only)

4.

Specially identifiable expenses. ii.

Apportionment Schemes for Multiple D’s:

1.

Joint & Several Liability (minority) a.

Ex: A- 80%, B- 20%. P can get damages totaling 100% from either A or B. A can ask for B’s share, but won’t get it if B is unable to pay through insolvency or immunity.

2.

Several Liability (most states) a.

Ex: A- 80%, B- 20%. Each D is only responsible for their share. If A is judgment proof, P only gets B’s 20% share of the award. b.

Also called proportionate or comparative fault. k.

Cause-In-Fact i.

“But For” Test:

1.

But for D’s negligence, would P’s harm have occurred?

2.

If no difference in what actually happened compared to what should have happened, then there is CIF (Salinetro). ii.

Substantial Factor Test:

1.

Is D’s negligence a material or substantial element in causing the injury?

a.

A substantial factor is one that has such an effect in producing harm as to lead a reasonable person to regard it as a cause (Anderson).

2.

Used if: a.

Where several causes occur to bring about an injury and one alone would have been sufficient to cause the injury.

All are causes of negligence (Duplicative Causes) b.

There are odd results arising from the “but for” test. c.

Ex: Two fires burn down P’s home. i.

Either cause would have been sufficient by itself to bring about the harm. ii.

If D’s cause and another unknown cause, then D’s cause must be sufficient alone to bring about harm. iii.

Alternative Liability: Summers v. Tice Test

1.

1 party responsible, but we don’t know which one.

2.

Burden of proof is shifted to Ds to show which one caused the injury. If one cannot be found liable, then both Ds are joint and severally liable (Summers).

3.

Applied when P shows all Ds are negligent and that other persons were not and could not have been the cause of the harm suffered

(Baxter Healthcare). iv.

Situations with an Indivisible Injury:

1.

An injury by its nature that cannot be apportioned with reasonable certainty to individual wrongdoers.

2.

Defendants are held Joint and Severally liable (Landers). v.

Lost Chance Analysis: (Lord)

1.

Traditional Tort Approach a.

P must be deprived of at least a 51% chance of a more favorable recovery as a result of D’s negligence. b.

P would get damages for entire injury.

2.

Relaxed Causation Approach a.

Less than 51% chance ok. b.

All damages recovered.

3.

Lost Opportunity Approach (Approach taken in Lord) a.

Lost Opportunity is the actual injury. b.

Less than 51% chance ok. c.

Recover only for value of lost opportunity. d.

Damages awarded by taking total value of injury and determining lost opportunity percentage. i.

Ex: Paralysis 100% = $100,000. 40% chance of full recovery w/o negligence. P gets $40,000. vi.

Multiple Defendants:

1.

Concert of Action- joint and several liability

2.

Indivisible Injury- joint and several liability

3.

Duplicative/Multiple Causes- substantial factor analysis l.

Proximate Cause

i.

Def: An actual cause that is substantial factor in resulting harm.

1.

Substantial refers to whether the harm created is of the same general nature as the foreseeable risk created by D’s negligence. ii.

Thus, the harm created must be in the scope of the risk created by the defendant’s negligence.

1.

General inquiry: Risk v. Outcome. Was the outcome within the scope of the risk. iii.

Basic Jury Instruction:

1.

Whether there was a natural and continuous sequence between the cause and effect.

2.

Was the one a substantial factor in producing the other?

3.

Was there a direct connection between them, w/out too many intervening causes?

4.

Is the effect of cause on result not too attenuated?

5.

Is the cause likely to produce the result?

6.

By the exercise of prudent foresight, could the result be foreseen?

7.

Is the result to remote concerning time and space from the cause? iv.

Liability limiting principles:

1.

Unforeseeable Plaintiff (Palsgraf)

2.

Unforeseeable manner of harm.

3.

Unforeseeable extent of harm.

4.

Intervening/Superseding cause. v.

Unforeseeable plaintiffs

1.

A defendant is liable only for types of injuries risked by his negligence (scope of risk) and to classes of persons risked by his negligence. Plaintiff must be within the foreseeable zone of danger. vi.

Manner of Harm

1.

If harm resulted from a mere variant of what was foreseeably expected, then there is still proximate cause. (Hughes)

2.

If harm resulted from something that is completely different that what was expected, no proximate cause.(Doughty) vii.

Extent of Harm

1.

Thin skull rule: If negligence is of kind that would cause harm to a normal person, or D knew or should have known of P’s condition, the fact that the harm was worse than expected doesn’t limit D’s liability. D takes the plaintiff as he finds him. viii.

Intervening/Superseding causes

1.

If there are two tortfeasors acting in sequence, the first often argues the second in an intervening cause that supersedes his liability entirely.

2.

An intervening cause will relieve the first tortfeasor of liability only where the resulting harm is outside the scope of the risk created by the first tortfeasor. (I & S) a.

If the resulting harm is within the scope of the risk, it is not a superseding cause, and liability remains. (I)

b.

(Deridarian, Ventricelli) ix.

Superseding Cause w/ Time Lapse

1.

When P is done coping with the consequences of D’s negligence, the situation returns to normal, and the previous negligence is not the proximate cause of future harms caused by other parties.

(Marshall) x.

Emerging Trends in Proximate Cause (minority)

1.

Intervening/Superseding cause instructions are not used unless alleged conduct is criminal, an intentional tort or a force of nature.

(3 states and 3 rd

Restatement)

2.

Reason: Proportional liability serves the same liability-limiting functions of proximate cause and avoids the confusion by I/S cause instructions. m.

Affirmative Defenses i.

Negligence of Plaintiff

1.

Contributory Negligence a.

If P could have avoided injury by exercising ordinary care,

D is not liable. b.

P only prevails if D is 100% negligent. c.

There can be no contributory negligence where the breach alleged would have prevented the negligence that occurred.

(Bexiga)

2.

Comparative Negligence a.

Pure CN: P can be any % at fault and will still be able to collect from D for D’s share of fault. b.

Modified CN: P can only recover if his fault is less than

D’s. 49-50 % is the cut off. c.

A BPL form of analysis is used to decide how to apportion fault. Costs to D to avoid injury are compared to costs to P to avoid injury. If both same, each 50% liable. (Wassell) d.

Exceptions: i.

Negligence to be prevented is in scope of D’s duty:

1.

There is no comparative negligence where the D’s duty of care involves preventing the self-abuse or self-destructive acts that caused the injury. ii.

Medical Malpractice:

1.

Patient’s negligent conduct that occurs prior to a healthcare provider’s negligent treatment and provides only the occasion for the provider’s subsequent negligence may not be compared to the provider’s negligence.

3.

Plaintiff’s participation in Criminal Acts a.

When P’s injury is a direct result of his knowing and intentional participation in a criminal act, he cannot seek

compensation for loss if the criminal act is judged to be so serious an offense as to warrant denial of recovery. i.

Must be substantial or serious in that there is a government interest in criminalizing the conduct, or there is a concern for public safety. (Barker) ii.

This applies where parties in the suit were involved in the underlying criminal act and where criminal seeks to impose a duty arising out of the illegal act. n.

Assumption of the Risk i.

Express AOR

1.

Need not be in written form. (Boyle v. Revici)

2.

For essential services (medical care), parties do not acquiesce voluntarily in the contractual shifting of the risk. No compulsory

AOR.

3.

Harm must also be within the scope of the release. (Moore v.

Hartley Motors)

4.

Analysis: a.

Is there a contract, agreement? i.

Oral or Written b.

Is it enforceable? i.

Tunkl- voluntary acquiesance? c.

Is what happened within the scope of the release? i.

Moore- no mention of general negligence in the release form. ii.

Implied AOR (contributory negl. States)

1.

P consents to Ds conduct. He consents if he… a.

Knew of the risk. b.

Appreciated the risk. c.

Voluntarily exposed himself to the risk. (Crews v.

Hollenbach).

2.

Comparative Negligence. a.

Assumed risk is merged into comparative negligence system.

3.

D did not breach a duty to P, either… a.

Because of Ps consent. b.

Because no duty on policy grounds. c.

Because no negligence on policy grounds.

4.

Sporting Event cases a.

Known, apparent and foreseeable dangers of a sport are not actionable, since you consent to them while participating in sport. (Turcotte v. Fell) i.

Ds duty is to exercise care to make conditions as safe as they appear to be. If risks of activity are obvious, P has consented to them and D has performed its duty.

b.

If implied AOR abolished, analysis shifts to Ds duty under the circumstances. The duty in athletic events is to avoid reckless disregard of safety. (Gauvin v. Clark)

XIII.

Duty of Landowners/Possessors a.

Applicable when P sues D landowner for injuries incurred on Ds land. b.

Duty to Invitees i.

Def: Rightfully come upon the premises of another by invitation for some purpose which is beneficial to the owner. ii.

Public invitee- land open to public (customer in store). iii.

Business Invitee- connected with business dealings of land. (repairman) iv.

Possessor is subject to liability for physical harm caused to them by his failure to carry on his activities with reasonable care if, but only if:

1.

He should expect that they will not discover, realize or fail to protect themselves against the danger.

2.

No liability for dangerous conditions that cannot be discovered through the exercise of reasonable care. c.

Duty to Licensees i.

Def: A person who is privileged to enter or remain on the land only by virtue of the possessor’s consent (including social guests). ii.

Possessor is subject to liability for physical harm caused by his failure to carry on his activities with reasonable care if, but only if:

1.

He should expect they will not discover or realize the danger or the risks involved in the activities. iii.

Possessor is subject to liability for physical harm caused by a condition on the land if, but only if he

1.

Knows or has reason to know of condition and realizes it involves unreasonable risk of harm to licensees

2.

And fails to exercise reasonable care to make condition safe, or to warn

3.

And licensees do not know or have reason to know of the condition and the risk involved. d.

Duty to Trespassers i.

Def: Any person who has no legal right to be on another’s land and enters the land without the express or implied consent of the landowner. ii.

Known/Anticipated trespassers: ordinary care to avoid injury. iii.

Unknown trespassers: refrain from willful and wanton conduct.

1.

Willful: intent, purpose or design to injure.

2.

Wanton: failure to exercise any care whatsoever. e.

Attractive Nuisance Doctrine (Bennett v. Stanley) i.

A landowner is liable for physical harm to children trespassing thereon caused by an artificial condition upon the land if:

1.

The place where the condition exists is one upon the possessor knows or has reason to know that children are likely to trespass, and

2.

The condition is one of which the possessor knows or has reason to know will involve an unreasonable risk of death or serious bodily harm to such children, and

3.

The children because of their youth do not discover the condition or realize the risk involved in intermeddling with it or in coming with in the area made dangerous by it, and

4.

The utility to the possessor of maintaining the condition and the burden of eliminating the danger are slight as compared with the risk to children involved, and

5.

The possessor fails to exercise reasonable care to eliminate the danger or otherwise to protect the children. f.

Open and Obvious Danger Rule (O’Sullivan v. Shaw) i.

Landowner has no duty to protect from injury where the dangers would be obvious to persons of average intelligence. ii.

If D could not foresee that P would not exercise reasonable care. No foreseeability = no duty. iii.

O & O danger depends on not just what people can see, but also on what they know and believe about what they can see. g.

In States where the 3 categories are abolished, general duty of care is substituted and categories are used to determine foreseeability of injury, and thus landowner’s immunity (Rowland v. Christian) i.

Closeness of connection between the injury and Ds conduct. ii.

Moral blame attached to Ds conduct. iii.

Policy of preventing future harm. iv.

Prevalence and availability of insurance.

XIV.

Non-Feasance a.

Def: Actors are not liable for failures to act under common law. No duty to take active or affirmative steps for another’s protection. i.

Misfeasance is actionable- negligence in doing something active. ii.

Nonfeasance is not actionable- doing nothing.

1.

You cannot do unlawfully what you can do lawfully. (Newton v.

Ellis)

2.

There is no legal duty to act is D does not place P in a position of peril. (Yania v. Bigan)

3.

Individuals are responsible for their own actions and are not liable for others’ independent misconduct. (Rocha v. Faltys) b.

Threshold question: Is there a duty? i.

If nonfeasance, no duty. c.

Exceptions to the no duty rule i.

If D knows or has reason to know that conduct has caused harm to another, there is duty to render assistance to prevent further harm. ii.

One who voluntarily renders services to another is liable for bodily harm caused by his failure to perform such services with due care or with such competence and skill as he possesses (Wakulich)

1.

If person places other in no worse position than before by his involvement, no liability (Krieg v. Massey) iii.

If there is a joint undertaking, one must help the other if he is in peril and can do so without endangering himself (Farwell v. Keaton) iv.

If person has created an unreasonable risk of harm, even innocently, there is a duty of reasonable care to prevent the harm from occurring. v.

Statutes and ordinances requiring a person to act affirmatively for the protection of another.

XV.

Duty to Protect from Third Persons a.

The general rule is no duty. b.

Exceptions: i.

Special Relationship between D and P.

1.

Carrier-passenger

2.

Inkeeper-guest

3.

Landowner-lawful entrant a.

Social host-licensee not a S.R.

4.

Employer-employee

5.

School-student

6.

Landlord-tenant

7.

Custodian-person in custody ii.

Special Relationship between D and 3 rd

Party c.

Ds Relationship with P i.

Specific Harm Approach

1.

Too restrictive. ii.

Prior Similar Incidents Approach

1.

arbitrary results. iii.

Totality of the Circumstances Approach (majority)

1.

#, location of prior similar incidents

2.

Foreseeability- known or should have known iv.

Balancing Test (minority- CA, LA, TN)

1.

Burden v. Foreseeability. d.

Ds Relationship with 3 rd Party (dangerous persons) i.

If there is a relationship, there is a duty to warn or duty to control.

1.

If landlord has control over danger from tenant, he has duty of care to legally get rid of the dangerous condition. (Rosales v. Stewart)

2.

Parents are liable for acts of their children if they know or should know of specific, dangerous habits. Parents must have ability to control.

3.

Therapists owe legal to duty to patient and his potential foreseeable victims if the patient poses a serious threat of danger to others.

(Tarasoff v. Regents UCA) a.

This duty applies when the 3 rd party poses a predictable threat of harm to a named or readily identifiable victim.

(Thompson v. Cty. Alameda) b.

Minority view is foreseeable harm to someone.

ii.

Negligent Entrustment

1.

Owner has knowledge of person’s incompetency, inexperience or recklessness and still entrusts his property to another with permission to use.

2.

Owner must have actual or constructive knowledge of person’s defects, evinced by mental/physical disability, youthful age, mental impairment, physical handicap or intoxication.

XVI.

Emotional Harm a.

Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress i.

Elements:

1.

D acts intentionally or recklessly a.

Producing distress must be intended or primary consequence.

2.

Conduct was extreme or outrageous * a.

Conduct is outside the bounds of what is expected as civilized conduct as to the P.

3.

Actions of D caused Ps E.D.

4.

Resulting E.D. was severe (based on reasonable person). ii.

For the workplace:

1.

P must show the existence of some conduct that brings dispute outside the scope of ordinary employment dispute into extreme and outrageous conduct. a.

Pro P viewpoint: employment entitles employee to greater degree of protection. b.

Pro D: court looks at employer’s interest in management of employees/workplace. iii.

Hostage situations/Felonious kidnapping:

1.

Exception to presence requirement. Lack of presence of loved one is cause of the distress. Immediate family may recover (parents, children, siblings). b.

Negligent Infliction of Emotional Distress i.

Types of Cases

1.

Direct Victim Cases: Ds negligence directed at P.

2.

Bystander Cases: Ds negligence directed at 3 rd

party and P is emotionally affected by what has happened to the 3 rd

party.

3.

Direct Victim cases in which D breaches an independent duty owed to P. ii.

Fright or Shock from Risks of Physical Harm

1.

Liability for Fright- Direct Victim a.

Impact Rule- no longer used i.

No recovery for fright alone, nor for its consequences, even physical consequences.

Physical injury required. (Mitchell) b.

Physical Manifestation Rule- dominant.

i.

No recovery for fright alone. Where no impact, P must produce evidence of physical harm resulting from shock or objective physical manifestation of shock occurring after events in question. c.

Objective Corroboration Rule i.

Requires medically diagnosable emotional injury. d.

Corroboration from Facts- minority.

2.

Emotional Harm Resulting from Injury to Another

1) General Mental Distress Claim a.

Zone of Danger i.

To recover for NIED, worker must be in the zone of danger of physical impact to recover for emotional injury caused by fear of physical injury to himself. b.

Dillon Approach (minority- PA, NJ) i.

Ps location to the cause of the emotional injury; close or far? ii.

Shock results from direct observance as contrasted from learning from others afterward. iii.

Whether P and victim are closely related. c.

Thing Approach i.

P must be closely related to the victim. ii.

P must be present at the scene. iii.

P must directly observe and be aware of victim’s injury. iv.

P must suffer severe E.D. v.

Exception : If D has pre-existing duty because of special relationship to protect from ED, rules no apply.

2) Loss of Consortium d.

Legal harm is ongoing sense of loss of injured party in relationship’s company, society, co-operation, affection. e.

Parents of a tortiously injured adult child cannot recover for loss of consortium. (Boucher v. Dixie Med. Ctr.)

XVII.

Vicarious Liability (Respondeat Superior) a.

Policy Underpinnings i.

Accidents that occur within the scope of employment are a cost of doing business; this cost is distributed among those that benefit from the business through insurance and in the price of the product. b.

Basic Test: i.

Whether the act was performed while doing the employer’s work (scope of employment). (Riviello) c.

Going and Coming Rule i.

Generally, an employee going to and from work is outside the scope of employment and the employer is not liable for his torts. ii.

Exceptions:

1.

Benefit to Employer: a.

Where the trip involves an incidental benefit to the employer, RS applies. b.

An employer receives substantial benefit from providing travel expenses to employees to enlarge the available labor market. Where the Er and Ee make travel time part of the work day by their contract, RS applies. (Hinman v.

Westinghouse)

2.

Special Hazards: a.

Distance alone does not constitute a special hazard.

3.

Dual Purpose a.

The Ee performs a concurrent service for the Er while commuting (picking up another Ee).

4.

For all, Er’s benefit must be the predominant purpose of the trip.

Benefit and control of Er are weighed against the personal nature of the trip. d.

Frolic & Detour i.

An act is not within the scope of employment if it is done with no intention to perform it as part of or incident to a service on account of which Ee is employed. (Edgewater v. Gatzke) ii.

Frolic-- Going to a place not associated with employment for a purpose not associated with employment; not considered within the scope of employment.

1.

Look for re-entry: the frolic is over and RS can be triggered. iii.

Detour—Trivial departure from the job that is reasonable under the circumstances; employer remains liable.

1.

Ex: Smoking (Edgewater) e.

Intentional Tort Liability i.

Employer not liable for assault or intentional torts that do not have a causal nexus to the employee’s work.

1.

The risk of injury must be a foreseeable consequence of the Er’s enterprise.

2.

Motivating emotions must be fairly attributable to work-related events or conditions. a.

The act must be one which is fairly and naturally incident to the business, is done while the servant was engaged upon the master’s business and arises from some impulse of emotion which naturally grew out of or was incident to the attempt to perform the master’s business.

XVIII.

Products Liability a.

Three Claims i.

Negligence ii.

Breach of Warranty iii.

Strict Products Liability b.

Rule of Strict Liability- Rest. 2d Torts, § 402A. P must establish:

i.

Product was in a defective condition ii.

Product was unreasonably dangerous for its intended use, iii.

Defect existed when product left Ds control, and iv.

Defect proximately caused the injury sustained. c.

Three types of Defects i.

Manufacturing Defects- flaws in production, physical departure from products intended design (few products) ii.

Design Defects- design is defective; all products unreasonably dangerous. iii.

Information Defects- failure to warn of problems with product. d.

Manufacturing Defects (Lee v. Crookston Coca Cola Bottling Co.) i.

Mere fact of injury during use is insufficient proof to show existence of defect at the time product left Ds control. ii.

D is not insurer of product regardless of circumstances. e.

Design Defects i.

Risk Utility Analysis: majority

1.

Benefits of Design do not outweigh risks inherent in it.

2.

Weigh by assessing factors: a.

Likelihood design will cause injury. b.

Gravity of danger posed. c.

Mechanical/economic feasibility of improved design. ii.

Consumer Expectations Test: minority

1.

Product must fail to perform as safely as an ordinary consumer would expect when used in an intended or reasonably foreseeable manner. f.

Information Defects- Duty to Warn i.

A failure to provide appropriate info about a product may make an otherwise safe product dangerous and defective. ii.

A warning can convey that a place, thing or activity is dangerous, or that a safer way can be undertaken to limit the risk. iii.

Heading Presumption: Courts will presume that people will heed warnings; D may prove otherwise. g.

Defenses i.

Misuse is not an affirmative defense in PL actions, but is to be treated in connection with the plaintiff’s burden of proving an unreasonably dangerous condition and legal cause. P must prove that the legal cause of the injury was a defect which rendered the product unreasonably dangerous in a reasonably foreseeable use.