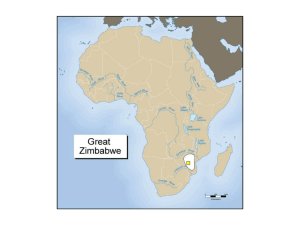

Zimbabwe: An End to the Stalemate?

advertisement