Practices supporting intertextual reading using science knoweldge.

advertisement

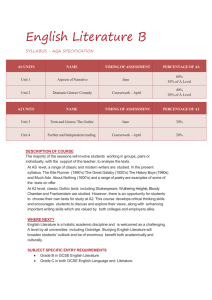

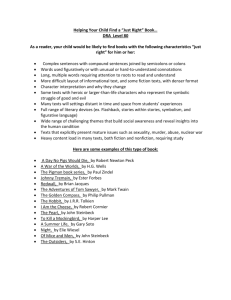

Reading Scientifically: Practices supporting intertextual reading using science knowledge Subject/Problem National standards call for students to learn about and participate in scientific inquiry (National Research Council, 1996, 2000). This places practitioners at the center of enacting research-based findings about inquiry. This becomes problematic as elementary teachers face many curricular demands for student performance (Mathison & Freeman, 2003). One recommendation is to develop integrated learning experiences including reading appropriate text genres in science learning (C. Ford, Yore, & Anthony, 1997; D. Ford, 2004; Hapgood, Magnusson, & Palincsar, 2004; Magnusson & Palincsar, 2004; Pappas, Varelas, Barry, & Rife, 2004). While there is limited research on effective approaches to integrating science and literacy (Cervetti, Pearson, Bravo, & Barber, 2006), researchers agree that integrated approaches benefit science and literacy learning. Furthermore, a primary research focus of science-literacy integrations – with a few exceptions – focuses on scientific knowledge to be learned through literacy processes. This research sought to explore and build on prior pilot research (Enfield, 2007) that investigated how text genres related to stimulating student driven inquiry. This study extends on that work. The study follows two research questions. How can teachers facilitate dialogic discussion (see Billings & Fitzgerald, 2002) situated in read-aloud events of narrative and informational texts in elementary science teaching? How does this create a situated context that supports students learning to read scientifically? There is a growing body of research about use of informational texts in elementary teaching. Elementary teachers infrequently use informational texts, resulting in students who lack of familiarity with genre and struggle to learn from these texts (Duke, 2000). However, informational texts in elementary classrooms provide students experiences with the language scientists use, provide prototypical experiences with experiences of science, can model for children how scientists build theory from data, and serve as tools in inquiry to facilitate students’ sense-making (Pappas et al., 2004; Varelas & Pappas, 2006). Furthermore, authentic experiences, experiences in which texts are used for purposes that mimic those in the real world, have the greatest influence on children’s familiarity with the genre (Purcell-Gates, Duke, & Martineau, 2007). Additionally, uses of informational texts can support development of conceptual understandings as well as understandings of the nature of science (Smolkin & Donovan, 2001; Girod & Twyman, 2009). However, the majority of this work argues for uses of informational texts and even argues for how narratives in science learning can be problematic (Smolkin & Donovan, 2001). An important consideration is the role of teachers in facilitating students’ use of informational texts (Ford, 2004; Donovan & Smolkin, 2001). The genre itself, as well as teachers’ assumptions about the genre, effects the selection of texts for use in science learning experiences. Teachers tend to choose text because of their assumption that students feel science is boring. These assumptions effect not only teachers’ selection of texts, but also the ways that they read those texts in classrooms. (Donovan & Smolkin, 2001) However, this point should be considered against the idea that individuals textualize their experiences in the world and that juxtaposition of multiple texts about the world is important to developing understandings (Blome & Egan-Roberston, 1993). From this perspective to counteract problems in discussions during read-aloud events, the teacher can share power with students as well as engage in students’ textualized experiences, which can result in students making connections to their personal experiences resulting in greater comprehension of informational texts. Engagement with students’ textualized experiences reflects findings describing how discussions about informational texts provide opportunities for teachers and students to engage in dialogic inquiry (Pappas et al. 2004). Since it has been argued that students can connect their experiences more readily with narratives (Short & Pierce, 1990), we might speculate that ‘reading scientifically’ may benefit from an intertextuality that reflects multiple text genres. Thinking about the construct, ‘reading scientifically’ relates to previously documented benefits of intertextuality in making meaning from texts in science learning (Varelas & Pappas, 2006). The findings and the construct of intertextuality support an argument that science and literacy learning can benefit from engagement with texts using participants collective body of knowledge and experiences to examine, question, and wonder about the claims, events, or ideas presented. This becomes a kind of critical literacy that has been shown to be useful in both improving comprehension as well as science learning (Cervetti et al., 2006). This study conceptualizes such intertexuality that engages in critical literacy as ‘reading scientifically’ – a construct that needs further research. Theoretical Framework This study assumes that learning occurs as a result of activity in a situated context. In these contexts, participants collaborate to communally validate what constitutes meaningful questions and inquiries (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Situated activity can occur in discussions that allow dialogic interactions which define meanings and participants in relation to one another (Bakhtin, 1986). From this perspective, communities both define contexts and explanations that are meaningful to the members of the community and the questions and evidence that will be validated as relevant and useful. Furthermore, defining text as any symbolic representation of meaning (Wells & Chang-Wells, 1992) means that texts become part of and products of the situated context. Texts support development of intrapersonal mental functioning. This facilitates epistemic engagement, which facilitates social action (Wells & Chang-Wells, 1992). Individuals’ actions are impacted by institutional, cultural and historic knowledge and tools embedded in personal repertoires; referred to as mediational means (Cobb & Bowers, 1999; Wertsch, del Rio, & Alvarez, 1995). Mediational means can include subject matter knowledge, strategies for engaging with and making sense of texts, and experiences in the world and with texts that enable reasoning with and about concepts, ideas, and phenomena represented in texts. Teachers, as participants with more robust and complex repertoires of knowledge, can mediate students’ participation in that context. Lave and Wenger (1991) also theorize that situated in contexts engage participants in resolving some implicit or explicit dilemma. Dilemmas involve participants in negotiation to arrive at shared, collective understanding. Thus, teachers and children have shared responsibility for learning and collective development of understanding. Connecting this with practice, teachers and students can share responsibility to resolve a dilemma around text. Engagement with text replicates inquiry processes, including identification of problems/questions and then defining procedures to answer those questions. The theoretical perspective elevates the notion of the problem as crucial to development of situated learning and defines the construct of ‘reading scientifically’ as engagement with texts to identify or resolve problems. Design and Procedures The study took place in two classrooms in a neighborhood elementary school in an urban district (Weiner, 2000). Consistent with typical assumptions, the students were predominantly minorities from low-income families. In the past the school has struggled to meet state assessment standards as required for AYP under NCLB; this year the school met AYP. Contrary to common assumptions, both classrooms were well equipped with materials, books, and supplies. In both classrooms, whole group instruction was limited but did occur. In all content areas there was limited use of textbook based curriculum materials. Finally, students had experiences talking about their ideas during teacher directed discussions. The data for this study were collected using purposive sampling (Patton, 1990). The researcher invited teachers based on past experience with the teachers, the researcher’s knowledge of the teacher’s pedagogical approaches, and the teacher’s willingness to participate. The study focuses on whole-group, classroom interactions, making classrooms and lessons the units of analysis. Primary data for this study are video recordings of reading events includeing pre-reading activities, the read-aloud, and any follow-up discussion that occurs in conjunction with the readings. Videos were reviewed and coded using HyperResearch. Then transcripts were analyzed using discourse analysis procedures. Additional data sources include field notes, informal interviews with teachers, and email exchanges between the teacher and the researcher. The theoretical framework for the study guided the analytic framework examining students’ discourse during discussions. Thus analysis focused on instances of intertextuality with texts read and utterances that led to instances of inquiry. The analysis focuses on students’ utterances in whole group discussions informational and narrative texts. Following Pappas et al (2004), transcripts were examined for utterances that represent instances of intertextual engagement with text. Related to this, discourse actions were annotated to determine how specific actions affected the situated context. Finally, the transcripts were examined for attributes of inquiry as described in the National Science Education Standards (2000). Findings This study focused on teacher actions and the ways that actions impacted the context of learning for students. Thus findings are presented here according to these interacting elements. First, these findings will describe the teachers’ actions in terms of uses of texts in science learning experiences. Within these findings, it is possible to consider the ways that the teachers’ actions created contexts that supported students learning to read scientifically. Teachers’ Actions In this study, the two participating teachers engaged in a number of actions in discussions to facilitate dialogic discussions. The teachers used relatively typical comprehension strategies with students. For example both of the teachers engaged students in substantial discourse around pre-reading strategies to stimulate interest, raise questions, and help the students to apply ideas of strategic reading in the context of a read-aloud experience. In many ways, the reading events allowed teachers to model reading strategies for children. In addition, the teachers engaged in some reading strategies that facilitated inquiry both about texts and also about phenomena. The following graph summarizes categories and numbers of actions taken by the two teachers in this study. This figure highlights the different actions teachers made in the discussion. The important points for this paper involve the number of questions that teachers asked about pictures and phenomena in the texts. These actions both scaffolded and modeled for students modes of engagement with texts that can be productive. However, looking across the two cases, it is possible to consider a couple of aspects of the teachers actions that seem important todeveloping an inquiry stance toward texts in science learning. One aspect to consider is how the teachers shared autority with their students. This became important in providing opportunities for student generated inquiry. The second aspect of teacher action involved the ways that teachers mediated discourse in the classroom to scaffold students’ engagement with texts. Shared Authority Throughout the observed lessons, both teachers shared limited authority with students, which resulted in more focused, teacher-directed discussions. For example, both teachers used pre-reading strategies in order to engage children with the text. But, in all cases the teacher led discussion about pre-reading by asking questions in an IRE pattern that limited students’ opportunities to engage with or direct the discussion. Teachers asked students to look at the cover illustration, recall prior lessons, or recall prior knowledge related to the text. Teachers did attempt to provide a purpose for reading that might establish authenticity. However, again these purposes were established by the teachers and did not engage students in developing or identifying a purpose for reading. One observation that arises out of the teachers’ actions involves how the pre-reading varied according to genres. During readings of informational texts, teachers’ pre-reading focused on students’ prior conceptual knowledge and experiences. For example, when reading an informational book about how forces affect the motion of objects, the teacher asked students to recall their first-hand investigations as well as the ideas that they had learned in prior lessons before reading the book. In contrast, during readings of narrative texts focused on activating prior literary knowledge and experiences from other readings. The same teacher in the same unit read the book Mirette on a High Wire. During the pre-reading of this book the teacher focused on the Caldecott award and students’ prior experiences with Caldecott award winning books. She also talked about how she was excited about the illustrations in the book because she thought the pictures were ‘beautiful’. Regardless of these observations, a more important point is that both teachers controlled and, to some extent, dominated the discussions providing students few chances to invest themselves or their own ideas into the reading events. Primarily, students responded to teacher questions and prompts. This results in a context that limits opportunities for student generated inquiries about the ideas or phenomena in the text. Mediation of Discourse The teachers’ actions mediated students’ discourse to connect students’ experiences, the ideas in the texts, and designing first hand investigations. The idea of mediation in this case is that a teacher can either elevate a student comment or interpret a student comment so that the comment facilitates developing understandings or generating authentic student generated inquiry. As a result in both classrooms, the teachers’ actions seemed pivotal to transitioning from text to inquiry. A couple of cases highlight this point. Beginning with the lesson that focused on reading Mirette on a High Wire, students identified many relevant experiences. The students became very engaged with affective elements of the story. They made personal connections with the feelings of the characters and attempted to interpret why different characters might feel they ways that they did in the story. Students related these feelings to their personal experiences of successes and failures. The teacher took actions to mediate these comments, while also attempting to have students consider phenomenological aspects of the story. Students had previously done first-hand investigations of balancing, so they had some prior knowledge and experience with concepts in the story. At one point during the reading, the teacher attempted to have students consider an image that showed a high-wire walker cooking breakfast on the high-wire. The event in the story seems somewhat improbable, but even with teacher mediation, the students continued to focus on affective aspects of the story as opposed to phenomenological elements of the story. However, teacher actions can productively mediate discourse. For example, when the teacher read Roller Coasters, she was able to engage students in discussion that led to the generation of an inquiry-oriented question that resulted in a first-hand investigation. The teacher relied on students sharing their lived experiences riding roller coasters to identify a conceptual problem in their inferences about their experiences. One student, based on an illustration in the book, claimed that it was important that riders wear their seatbelts in the roller coaster because this prevented the rider from falling out when the roller coaster went through a loop. The teacher, using the pictures in the book, pursued the student’s claim and helped the students recognize that there was an implicit testable question in that claim. Based on this discussion, the class investigated objects moving through loops on tracks to determine if a restraint was needed to keep those objects on the track. Through first-hand investigations and explorations of simulations, the students explored the concept of centripetal force. These investigations were stimulated by the reading of the book, but also through the teacher’s actions to mediate students claims and the content of the book. Creating a context for students’ actions The teachers’ actions helped to create contexts for students to begin engaging with both texts and ideas. For the most part, in this study, the teachers constrained students’ opportunities to act by limiting the amount of authority students had in directing discussions. However, there remain interesting points about students’ actions that deserve attention. Similar to the teacher data presented above, the following figure describes the nature and frequency of students’ actions. This figure highlights some important features of the students’ talk. The students made several connections with the texts and also several comments about pictures in the text. Students made fewer utterances about vocabulary or comphrension. Students’ observations and comments Students made many observations and comments that related their personal experiences with the ideas, concepts or events portrayed in the text. Students’ utterances showed that the students were engaged with both genres of text and making connections to their lived experiences. For example, when reading about Come on rain, the students shared their own experiences on hot summer days (the context of the story) and how summer rain showers feel good on a hot summer day. Thus, the students were connecting their personal experiences with weather to phenomena portrayed in the story. However, this ultimately did not lead to generating an investigation of the relationship between temperature and precipitation. Students’ utterances were ripe opportunities to engage students in reading texts scientifically by engaging in inquiry experiences around ideas, concepts and events portrayed in texts. For example, when reading about evaporation and condensation, students identified many relevant personal experiences that could have stimulated further inquiry. Concurrent to reading informational texts about evaporation and condensation, students investigated these phenomena in the classroom. The teacher directed investigation reflected fairly typical approaches, using cups of water, ice, and ice water placed in different locations, and provided students with direct experiences with the phenomena. When reading narratives that included phenomena of evaporation and condensation, students did make limited connections to their experiences. But the problem was that the overall context was discretely compartmentalized. Each event – reading or first-hand investigation – was not connected to other, related events. Thus there were opportunities to engage in scientific reading, but these were not actualized in practice. Critically examining texts Seeing texts as including problematic symbolic representations of phenomena was less prominent in these classrooms. The teachers created contexts in which students were expected to focus on comprehension strategies. Thus, the context implicitly privileged getting information from text, as opposed to viewing texts as having values, impressions and beliefs that influence the writing. Both classrooms were devoted to developing students’ reading fluency and comprehension. As a result, there were limited opportunities for students to learn to or engage in critical examination of texts. However, there were limited exceptions. For example, during the reading of Down came the rain, the teacher initiated a discussion into the plausibility of events of the story. In the story, there had been a big storm, when the storm passed; the characters were immediately seen on a picnic. The teacher wondered about this with students, suggesting this it might be problematic. However, the students made few comments about this event in the story. In this study, there were few overall instances that involved students critically examining the story or phenomena represented in the texts. Teacher actions and student actions One important observation in comparing teacher actions and student actions involved the nature of their actions in the context. Teachers tended to make more comments focused on comprehension of the texts and developing comprehension skills. In contrast, students tended to ask questions about the texts and also making connections between the text and their experiences. Thus, the teachers and students seemed to have different purposes for reading and making connections between the text and science investigations. Discussion & Implications The findings reported in this study raise additional questions about the role of text genres in children’s science learning. Scholars have argued that narrative ways of knowing and reasoning are useful in making concrete connections between experiences and abstract phenomena. Regardless of this argument, in science, research has focused almost exclusively on a single genre – informational text. In the context of this study the teachers’ actions during discussion were pivotal to scaffolding students’ engagement with both genres. This supports prior suggestions that the role of the teacher is important (D. Ford, 2004; Pappas et al., 2004). The findings from this study suggest that teachers may need support to leverage the opportunities of texts to support inquiry learning, literacy learning, and learning to read scientifically. Thus, it may be useful to teachers to have content related lists of titles useful in engaging students in inquiry around narrative texts. Additionally, it may be useful to have recommended strategies (e.g. question types) that might be more effective in scaffolding student inquiry. This builds on thinking about the kinds of actions a teacher takes in situated contexts to engage children with texts. More specific to science, how can teachers use texts to stimulate inquiry? An implication from these findings involves considering how we think about the role of problems in science as being useful for thinking about integration of science into other content areas. Often our notions about integration focus on either topical integrations or following disciplinary perspectives (e.g. Schwab, 1978) to create authentic learning experiences. However these findings suggest potential for thinking about using the conceptual and epistemic nature of science as a mediator for integration. This would create a very different kind of integration that focused on highlighting the problematic nature of texts to launch investigation, inquiry, and units of study. Whitin & Whitin (1997) effectively describe this model of inquiry and integration. Yet, it seems that these ideas could be advanced further in science education. Finally it is important to note that these findings describe two classrooms. The findings do not: lead to causal claims, offer comparable cases to determine which genre more effectively supports inquiry, or offer generalizable claims. All of which suggest the need for further study and investigation to explore the implications of these findings. Furthermore, the findings should not lead to the inference that teachers should abandon efforts to increase uses of informational texts in elementary classrooms. We must continue to develop literate members of discourse communities. As such, students need abilities to engage with all genres of text. Furthermore, learning to read scientifically will be supported through experiences with multiple text genres. References Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres & other late essays (V. W. McGee, Trans.). Austin: University of Texas Press. Billings, L. & Fitzgerald, J. (2002). Dialogic discussion and the Paideia seminar. American Educational Research Journal, 39(4). Bloome, D. & Egan-Robertson, A. (1993). The social construction of intertextuality in classroom reading and writing lessons. Reading Research Quarterly 28(4). 305-333. Cervetti, G. N., Pearson, P. D., Bravo, M., & Barber, J. (2006). Reading and writing in the service of inquiry-based science. In R. Douglas, M. Klentschy & K. Worth (Eds.), Linking science and literacy in the K-8 classroom. Alexandria: NSTA Press. Cobb, P., & Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and Situated Learning Perspectives in Theory and Practice. Educational Researcher, 28(2), 4-15. Donovan, C.A. & Smolkin, L.B. (2001). Genre and other factors influencing teachers' book selections for science instruction. Reading Research Quarterly. 36(4). 412-440. Duke, N. K. (2000). 3.6 Minutes per day: the scarcity of informational texts in first grade. Reading Research Quarterly, 35, 202-224. Enfield, M. (2007) Could that really happen? Elementary children’s inquiry around informational and narrative texts. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, New Orleans, LA. Ford, C., Yore, L. D., & Anthony, R. J. (1997, March 1997). Reforms, visions and standards: A cross-curricular view from an elementary school perspective. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Oak Brook, IL. Ford, D. (2004). HIghly Recommended Trade Books: Can They Be Used in Inquiry Science? In E. W. Saul (Ed.), Crossing Borders in Literacy and Science Instruction: Perspectives on Theory and Practice. Newark: International Reading Association. Girod, M. & Twyman, T. (2009). Comparing the value added of blended science and literacy curricula to inquiry-based curricula in two second-grade classrooms. Journal of Elementary Science Education, 21(3). 13-33. Hapgood, S., Magnusson, S. J., & Palincsar, A. S. (2004). Teacher, text and experience: A case of young children's scientific inquiry. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(4), 455505. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Magnusson, S., & Palincsar, A. S. (2004). Learning From Text Designed to Model Scientific Thinking in Inquiry-Based Instruction. In E. W. Saul (Ed.), Crossing Borders in Literacy and Science Instruction: Perspectives on Theory and Practice. Newark: International Reading Association. Mathison, S., & Freeman, M. (2003). Constraining Elementary Teachers' Work: Dilemmas and Paradoxes Created by State Mandated Testing. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 11(34). National Research Council. (1996). National Science Education Standards. Washington DC: National Academy Press. National Research Council. (2000). Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Pappas, C., Varelas, M., Barry, A., & Rife, A. (2004). Promoting Dialogic Inquiry in Information Book Read-Alouds: Young Children's Ways of Making Sense of Science. In E. W. Saul (Ed.), Crossing Borders in Literacy and Science Instruction: Perspectives on Theory and Practice. Newark: International Reading Association. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qaulitative evaluation and research methods (2 ed.). Newbury Park: Sage Publications. Purcell-Gates, V., Duke, N. K., & Martineau, J. A. (2007). Learning to read and write genrespecific text: Roles of authentic experience and explicit teaching. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(1), 8-45. Schwab, J. J. (1978). Science, Curriculum and Liberal Education. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Short & Pierce (1990). Talking about books: Creating literate communities. Portsmouth: Heinemann. Smolkin, L.B. & Donovan, C.A. (2001). The contexts of comprehension: The information book read aloud, comprehension acquisition, and comprehension instruction in a first-grade classroom. The Elementary School Journal, 102(2), 97-122. Varelas, M., & Pappas, C. C. (2006). Intertextuality in read-alouds of integrated science-literacy units in urban primary classrooms: Opportunities for the development of thought and language. Cognition and Instruction, 24(2), 211-259. Weiner, L. (2000). Research in the 90's: Implications for urban teacher preparation. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 369-406. Wells, G., & Chang-Wells, G. L. (1992). Constructing knowledge together: Classrooms as centers of inquiry and literacy. Portsmouth: Heinnemann. Wertsch, J. V., del Rio, P., & Alvarez, A. (1995). Sociocultural studies: history, action, and mediation. In J. V. Wertsch, P. del Rio & A. Alvarez (Eds.), Sociocultural Studis of the Mind (pp. 1-36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Whitin, P., & Whitin, D. J. (1997). Inquiry at the window: Pursuing the wonders of learners. Portsmouth: Heinemann.