Kiwi Gothic - kapiticollege

advertisement

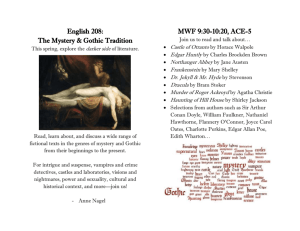

Kiwi Gothic Australia produces Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Muriel’s Wedding. New Zealand produces Heavenly Creatures, The Piano, and Scarfies. Has the Kiwi psyche gone over to the Dark Side? Only recently have we begun to realise how Gothic much of New Zealand’s literature and film is, says Dr Jenny Lawn of the School of Social and Cultural Studies at the Albany campus. “Commentators on New Zealand culture have discussed themes such as violence within families, alienation, abandonment, horror, and the mixture of fear and temptation associated with imagined stereotypes of Mäori in early New Zealand. In 1952, Bill Pearson characterised Päkehä New Zealanders as “fretful sleepers, living anxious, twilight, unfulfilled lives, haunted by their own conventionality”. However, it took an American critic, William Schaffer, to point out the obvious. “Schaffer toured New Zealand in 1997 and wrote a kind of traveller’s guide to New Zealand culture. What struck him most baldly was the Gothicism of so much of our cultural self-representation.” Gothic literature stems from the “Gothic revival” of the late 18th century, a period when hundreds of fantastical novels and melodramas were produced. Typically these works were set amid haunted castles, graveyards, ruined abbeys, and wild, craggy landscapes, often featuring young heroines who fight off threats to their virginity and rightful inheritance. But with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), the Gothic novel began to explore the idea of a divided consciousness, and it is this tradition of psychological horror that most influences Kiwi Gothic. “Dr Frankenstein and the monster that he creates can be seen as two facets of the same personality,” explains Dr Lawn, who suggests that early Gothic literature influenced some foundational thinkers in psychology and psychoanalysis. “In fact, as the essay The Uncanny shows, Freud picked up some of his key ideas from Gothic narratives, together with other literary classics such as Hamlet and Oedipus Rex.” Dr Lawn extends such connections between literature and psychology in her post-graduate block mode paper Trauma, Memory, Haunting. So what makes a story Gothic? Dr Lawn argues that the Gothic mode is not necessarily defined by content, such as the presence of bats, ghosts, haunted castles, and so on. “Instead, I look at the underlying phenomenological structure of the narrative and the psychology of the characters. By that I mean that the Gothic mode deals with a particular configuration of split space and time. For example, the stains of past generations frequently infiltrate the present action of the story. You also find that Gothic settings have a vertical dimension, whether that be a basement or attic in a house, steep hills or cliffs in landscape, or, more loosely, class divisions in the social setting.” Gothic is thus an adaptable genre, ever popular and evolving. Dr Lawn’s second-year Gothic course (139.275), offered internally in semester one at Albany, traces the development of the genre from its European roots to its widespread variants, such as American Gothic, Female Gothic, and Kiwi Gothic – including the blockbuster film The Rocky Horror Picture Show, written and directed by a New Zealander, Richard O’Brien. “When we discuss Kiwi Gothic,” notes Dr Lawn, “I start by asking students whether New Zealanders are haunted by anything. Answers have included the bush, distance, and a sense of relative existence overshadowed by larger cultures. Other students argue that New Zealand has matured as a culture to the extent that these elements of colonial life no longer provoke anxiety.” Dr Lawn argues that within New Zealand, the Gothic mode is concentrated in Päkehä literature and film, rather than in Mäori creative work published in English. “Gothic depends on an attempt to split light from darkness and modern reason from ancient superstition,” a division which proves impossible to maintain. “Mäori cosmology, by contrast, does not seem to split the spirit world from the material world in such a binaristic manner. In a novel such as Witi Ihimaera’s The Matriarch, for example, the world of light is called up through twelve orders of darkness. Likewise, death in novels such as Ihimaera’s Tangi or Patricia Grace’s Potiki does not terrify, but rather it galvanizes a community or family into political action.” Oddly, New Zealand literature has not produced any well-known examples of one of the most popular Gothic forms, the vampire story. “Our monsters tend to be interior: they are experiences of intense psychological states, often with sexual undertones within isolated nuclear families.” She points to Vincent Ward’s Vigil and Jane Campion’s The Piano as examples. Also typical of Kiwi Gothic, these films depict an intruder who disrupts a family or community, often exposing underlying stresses. In R. H. Morrieson’s ‘Taranaki Gothic’ novel The Scarecrow, for example, the necrophiliac murderer who invades the small provincial town of Klynham darkly enacts the more innocent sexual fantasies of the adolescent male protagonist, Ned Poindexter. A similar dynamic occurs in the Sarkies brothers’ film Scarfies. Named after the omnipresent item of clothing worn by University of Otago students, the film depicts the moral disintegration of a group of students following the discovery, and harvesting, of a cannabis crop in the basement of their flat. The students lock the angry owner of the dope in the basement, and his intrusive force manifests the students’ own jealousies and self-interests. Scarfies also continues a trend toward urban settings in Kiwi Gothic movies, notes Dr Lawn, which often reveal the nature of the city. “The class consciousness of Christchurch is fundamental to Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, for example. “Scarfies, I would suggest, evokes Dunedin’s Calvinist heritage when the students are placed in the position of having gained a material reward – the cannabis crop – that they have not worked for. And even The Irrefutable Truth about Demons, a horror film about the paranoid obsessions of an anthropology lecturer, conveys something of the self-analytical quality of the Wellington intelligentsia.” Because Dr Lawn’s course focuses on representation, students do not actually study real-life Goths, who dress in black with heavy black eye make-up, enjoy the droning bass of Gothic rock, and dwell on the aesthetics of death. “There is a thriving sub-culture in Auckland”, says Dr Lawn, “but I’m not a participant. I restrict myself to reading and writing about Gothic stories – that’s enough excitement for me!”