Sarah Blacker

advertisement

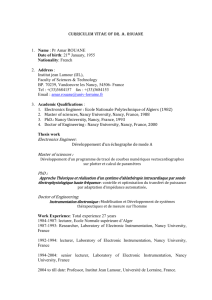

Blacker 1 Sarah Blacker Cultural Studies and Critical Theory Executive Committee Major Research Project Proposal Writing on the Body: The Graft in Jean-Luc Nancy and Jacques Derrida While existing research on organ donation in the humanities focuses on philosophical articulations of the “self”/”other” distinction in the context of organ donation (Fox and Swazey [1992]; Ross [2002]) and cultural beliefs regarding the sanctity of the body (Sharp [1995]; Belk [1992]), my project seeks to explore the problems and possibilities surrounding the notion of gift-giving between strangers by focussing on how the complexities of the gift of an organ unsettles our understanding of the nature of individual consent, patients’ interests, and societal expectations about the body of the one who is deemed to be the “stranger.” I argue that we need to find the means to radically revise our very concepts of the gift; this work is already complexly underway in the writings of Derrida (1992; 1995). In a now widely cited argument, Derrida argues that the “pure” gift, the gift that has, in effect, given away its status even as gift, is empirically impossible but conceptually necessary as the horizon against which gifts of more conventional kinds appear and become meaningful. The “pure” gift is, in other words, a counter-intuitive hazard or threat–a radically priceless “object” in a world that is otherwise wholly given over to getting and spending, and to understanding all phenomena as reducible to those terms. Does the mere prospect of organ donation between strangers hint at the possibility of the “pure” gift? Does its conceptual excess Blacker 2 vis-à-vis conventional, exchange-based understandings of social interaction account for the reluctance of policy makers and physicians to embrace donation between “strangers” (that is, those deemed “strangers” in the absence of “familial relatedness,” either through genetics or kinship)? My project seeks to develop new languages to address the nature of the gift and the consequences of gift-giving when the gift in question is an organ that appears to be given solely for the sake of being-given, yet is interpreted as an intruder inflicting violence upon the recipient. Nowhere is the unlikely affinity between contemporary philosophy and embodiment, theory and the question of transplantation, more complexly evident and consequentially alive than in Jean-Luc Nancy’s L’Intrus, a meditation on his heart transplant, subsequent lymphoma, and stem cell transplant. What happens when one of the world’s leading philosophers falls ill and reflects philosophically upon that illness? L’Intrus, first published in French in 2000 and translated into English by Susan Hanson for The New Centennial Review in 2002, is the ideal archive through which to explore theory of the gift, hospitality, the “stranger,” foreignness, and distinctions between “self” and “other.” Nancy’s text itself can be viewed as a grafting of “theory” into the body and “life proper” in that L’Intrus is a contemporary theorist’s meditation on his own experience of transplantation, and is thus an exceptionally rich text through which to examine theoretical questions in a “biomedical” context. The provocative title of Nancy’s text captures the reader’s attention even before the very first sentence is read: the intruder. For those readers who are aware of the subject matter Nancy addresses in his text, this title registers as curious, to say the least. Knowing that L’Intrus chronicles Nancy’s heart transplant, it seems counter-intuitive that Blacker 3 this experience would be characterized as one in which a being is intruded upon, rather than one in which a rare and priceless gift is received, health is restored, and a life is “saved” or preserved. Recalling Derrida’s assertion that “as good,” the gift “can also be bad, poisonous…the gift puts the other in debt, with the result that giving amounts to hurting, to doing harm” (Given Time 12), I view Nancy’s text as a meditation on the ambivalent valences of the gift—including the possibility of experiencing a gift as “poisonous” or “parasite.” In what sense, then, is the heart poisonous? The donated heart has zero capacity to function on its own; it is entirely dependent upon being housed within and connected to a functional human body in order to carry out its duties. This donated heart of an other is grafted into Nancy’s body when his own heart, his original heart, begins to fail. In order to accommodate this stranger, this other, within a bastion of sameness, Nancy’s immune system is pharmaceutically induced into a repressed state, its “natural” tendencies towards violence and rejection subdued. Is the donated heart not an unexpected and undeserved gift that miraculously arrives to do the work the diseased heart loses the ability to carry out? Nancy’s text does not take up the question of donated organ as panacea in a discussion of any significant length; instead, he characterizes the donated organ as a poisonous parasite upon the “proper” body. The text does not express a great deal of wonder and gratefulness in response to the receipt of such a vital body part from an unknown other. Instead, the donated heart is aligned with the parasitic, suggesting that the grafting of the other within the self inflicts great violence (psychically, at least, if not physiologically). What is the character of this violence? It seems, from Nancy’s account, that it is the structural changes to the body inflicted by the stranger within that Blacker 4 instantiate Nancy’s grief more so than the mere existence of alterity within the medicalized body. How is this insight instructive for our thinking of the ways in which we theorize our own dwelling with alterity, our sense of what constitutes the body “proper,” and what it means to be “healthy” and “whole”? Does Nancy’s account warn against the dangers of welcoming the other solely on our own accord, of feigning a hospitality towards the other that is actually an inhospitable welcoming only of the aspects of the other that are beneficial to the self, while jettisoning those that might require some compromise, upheaval, and revisions on our part? L’Intrus is a troubling text with respect its engagement with questions of “self” and “other,” interiority and exteriority, propriety, belonging, the “natural,” and the “strange” or “foreign” in a medical context. Indeed, Nancy’s characterization of his own post-transplant subjectivity as béance, or a “gaping open” (10), calls for a rethinking of subjectivity in an age of identity-restructuring medical technology. As Anne O’Byrne suggests, L’Intrus overturns a conception of subjectivity defined by “accessible exteriors hiding inscrutable interiors” (178). Through L’Intrus, Nancy reveals a previously inscrutable interior and invites us to think through the “intrusion” of the other’s organ as a gift enacting radical dispossession. This transplant constitutes a novel form of exchange that repels moralizing and reconciliatory gestures by provoking us to revalue force and violence, pointing towards a relation to foreignness that more closely resembles being-with than assimilation. With good reason, Christopher Fynsk describes L’Intrus as both a “testimony to suffering” and “a protest” (24) possessing a “striking asceticism, even austerity” (32). Fynsk views Nancy’s text as a chronicle of perpetual conflict and the impossibility for Blacker 5 reconciliation: a text that is, at its core, one of discomfort. However, Nancy’s account of the “conflict” seems restrained; it is difficult for the reader to discern the nature of Nancy’s personal experience of the “invasion.” As Fynsk points out, though L’Intrus is Nancy’s most autobiographical text to date, Nancy “largely removes himself from the narrative” (26). How strange and telling: a narrative that is confessional in its orientation but somehow anonymous in its content. My project seeks also to explore how this paradox itself constitutes an important part of Nancy’s reflection on the nature of “intrusion” and the self’s encounter with foreignness. Reading a text that is simultaneously rich but sparse can be a highly productive activity: that which Nancy gestures towards, but refrains from discussing within this space, begs for critical engagement. Nancy’s text points outside of itself with subtlety and grace at every juncture; it is in these openings, these provocations, that this project will locate its shape and direction. My paper will be taken up with a close reading of Nancy’s capacious text, structured by close critical attention towards and commentary upon the modes of expression and patterns through which we see several key theoretical concepts play out in Nancy’s text. More specifically, the project will be divided into two sections: the first section will trace out a framework featuring the Derridean genealogies of the key theoretical concepts to be employed throughout my reading of Nancy’s text, namely, the graft, hospitality, the stranger, and the gift; the second section will be comprised of my close reading of L’Intrus, through which I will propel Nancy’s words to enact a different type of theoretical work than they currently perform within a text that has received remarkably little critical attention. The very language with which we discuss identity in the context of organ Blacker 6 replacement surgery is important; it is crucial that discrepancies in terminology are laid out, even at this very early stage. As Peggy Kamuf notes, there is an incongruity in medical terminology employed to describe the surgical procedures Nancy undergoes. The terminology varies depending upon linguistic context: while in English, the procedure is referred to as a “transplant,” in French, it is a “graft.” There is a significant etymological difference between the two terms that is important to our discussion here. The semantic journey traveled by the word “transplant” is straightforward and uncomplicated: “transplant” is derived from the Latin transplantere, meaning “trans‘across’ and plantere- ‘to plant’, or ‘something or someone moved to a new place” (OED). Conversely, “graft” is etymologically derived from the Greek graphion, meaning “stylus, writing implement,” related to graphein: “write” (OED). I am interested in the way in which the act of writing lies dormant in our every utterance of “graft” and in each of our references to the procedure of the grafting of organs. While “transplant” implies a straightforward replacement of one faulty or diseased organ with a healthy, functional organ, “graft” reminds us that this procedure is not so simple or mechanical. ‘Transplant’ suggests a sterile, surgical procedure that promptly returns function to the ill patient, while “graft” points to a surgical event that is messy, and leaves a trace, pointing to the way in which the surgery is always-already a psychical event in excess of the visible scars that remind us of its occurrence. Furthermore, while “transplant” suggests a total doing-away with the old organ and its complete substitution with the new organ, “graft” more accurately reflects the inability to ever remove all traces of the first organ from the body, even if these traces remain solely in a spectral form. Instead, “graft” suggests a melding together of two disparate entities, forming a lasting attachment or collaboration. Blacker 7 This characterization of the surgical procedure is apt considering the ways in which the very concept of organ grafting so radically calls into question our comfortable conception of the individual’s absolute singularity as flowing out of a bodily integrity or wholeness that determines one’s identity. Organ grafting, then, enacts a specific type of writing on the body: it is writing that “renders the graftee a stranger to himself” (Nancy 9). Nancy suggests that following such a surgical procedure, an individual can no longer be ‘at home’ in his or her (divisible) body.1 For Derrida, the act of writing is indissociable from the act of grafting. In Dissemination, Derrida states: “[t]o write means to graft. It’s the same word…The graft is not something that happens to the properness of the thing. There is no more any thing than there is any original text” (355). Here, Derrida refers to the concept of the prosthesis and his assertion that every thesis is always-already a prosthesis (Glas 189). From this passage we can ascertain that every text we encounter is entirely constituted by grafts. So deeply entrenched is this process of grafting that it is impossible to locate any homogenous substance not formed out of a merging with another. Derrida emphasizes the covert nature of this grafting; this process of textual coalescence is imperceptible as the incisions leave no scars behind. Derrida writes of the grafted text: [i]t is the sustained, discrete violence of an incision that is not apparent in the thickness of the text, a calculated insemination of the proliferating allogene through which the two texts are transformed, deform each other, contaminate each other’s content, tend at times to reject each other, or pass elliptically one into the other and become regenerated in the repetition, along the edges of an overcast seam [un surjet] (Dissemination 355). In this rich passage we can identify the themes that constitute Nancy’s L’Intrus: violence, 1 It is important to interrogate the conception of bodily integrity and wholeness insinuated here when we compare the intruded-upon body to that which is supposedly ‘natural’, ‘originary’, ‘pure’, and ‘untainted by foreignness’. For, as Derrida reminds us, our bodies are always-already prosthetic, intruded-upon from the beginning. Blacker 8 proliferation, transformation, deformation, contamination, rejection, movement, regeneration, and repetition. If “[m]eaning is produced by a process of grafting” (Culler 134) and textual grafting is “inserting one discourse in another” (Culler 135), how is this instructive for our discussion of organ transplantation as “writing on the body”? Some of Derrida’s texts, including Glas, embody the graft through their form: two columns of text facing each other, continually reminding the reader that every text constantly refers outside of itself. By making it impossible to view a text as an entirely self-contained, homogeneous monolith, Derrida provokes us to view the text as an entity that is always-already indebted, and in relation to, other texts. What, then, does it mean to view Nancy’s physical body as a grafted text, an always-already prosthetic thesis? I want to explore what it might mean to view Nancy’s grafted body as the merging of two columns of text within one body. If we read Nancy’s body in the same way we read Derrida’s texts featuring oppositional columns, we cannot help but work towards a radical breaking down of the staunchly-enforced (within a medical model, at least) opposition between “self” and “other.” In his discussion of the graft in Derrida’s work, Jonathan Culler asserts that “[t]he graft is the very figure of intervention” (141). We will view the bodily graft in the same way for the purposes of this discussion: the graft for Nancy is perpetual intervention, displacement, and struggle. Identifying the locus of the graft in a text involves seeking out “the points of juncture and stress where one scion or line of argument has been spliced with another” (Culler 135). In the same way, Nancy’s L’Intrus is a chronicle of the “points of juncture and stress” arising out of the splicing of arteries. Nancy Blacker 9 characterizes these points as points of béance, or “gaping open” (10). The unending shifting and displacement within Nancy’s body is not merely the effect of the surgical incision that ushered in the intruder. Instead, Nancy attributes the internal struggle to “this gaping open [béance] that cannot be closed” (10). We see this structure of an open wound repeated in Derrida’s description of the grafted text as an entity that “limps and closes badly” (Derrida in Culler, 139). Perhaps we should view this stubborn structural openness as the locus or passageway of the pharmakos, or “scapegoat.” In the same way that the pharmakos is identified as “the evil that afflicts the city” (Culler 143), Nancy characterizes his donated heart as intruder and parasite within his body. In this way, Nancy’s grafted heart is the scapegoat that cannot be expelled from the city since the city would promptly crumble upon the intruder’s expulsion. Thus, the intruder is not welcomed and offered hospitality; instead, its presence is tolerated. However, we cannot view the donated heart alone as the graft, for as Derrida reminds us, the body as text is wholly comprised of grafts. Throughout Nancy’s text, we observe that the “intruding” heart oscillates between its status as remedy in the form of a gift of health and renewed life and its status as poisonous parasite. Culler asserts that this is the paradigmatic form assumed by writing as supplement in Derrida: “it is an artificial addition which cures and infects” (142). The pharmakon, or “intruder” for Nancy, features at bottom an ambivalence, perpetually morphing between two extremes as “the possibility of both poison and remedy” (143). At the beginning of his text, Nancy characterizes his receipt of the heart of another as a contamination rather than as a panacea for a medical affliction that imposed severe restrictions on his physical, cognitive, and emotional capabilities prior to the Blacker 10 transplant. As Fynsk suggests, there is an “irreducible discomfort, even…dispossession that comes with the advent of the strange” (25). Indeed, the intruder is discussed in relation to a gift-through-dispossession throughout the text. The accusation of dispossession, though, does not remain with the intruder; Nancy reveals a self that was always-already dispossessed when he identifies his own diseased heart in its limited, pretransplant functionality, as the originary intruder: “[m]y heart was becoming my own foreigner” (4). At the height of his illness, when the first heart becomes the intruder, Nancy’s self is defined wholly by its technical status in the context of medicine. Though his heart has betrayed him and is now working his body away from life and towards death, it is this same heart that entirely shapes his identity: “‘I’ am, because I am ill” (4). Now, the intruding diseased heart must be excised; its non-functionality necessitates the deployment of the stranger’s heart. At this moment, Nancy’s text demonstrates a decidedly conditional hospitality: the foreign heart is received in the absence of welcome, and solely out of desperation, as symbolized by the violent surgical incising of flesh to make way for the stranger. Indeed, Nancy’s text constantly evokes Derrida’s discussion of hostipitality in the sense that the reader is never certain whether the intruder will prove to be an enemy or an ally to Nancy as recipient. Within Nancy’s fascinating conceptual turn in which violence and intimacy become inextricably tied to one another, we see that distinctions made between health and illness, purity and contamination, and benevolence and destructiveness on the part of the intruder, can no longer be relied upon. As Nancy writes, “[w]hat cures me is what infects or affects me; what allows me to live causes me to age prematurely” (12). This provocation reminds us that this gift of an organ must be theorized in light of Derrida’s discussion of the gift as both present and poison. Blacker 11 Is Nancy’s discussion of a medically-imposed béance instructive for our thinking with respect to relationality between “self” and “other” and hospitality? Nancy characterizes his receipt of the intruder in the form of a functioning heart, along with pharmaceutical panaceas designed to repress his body’s “natural” tendency towards a rejection of the other being grafted on to his self, as a “disturbance and perturbation of intimacy” (2). But later on in his text, Nancy points to the possibility of an intimacy with alterity that is facilitated by immuno-suppressant drugs that both prevent the body from rejecting the grafted organ and allow other intruders, in the form of viruses and infections, to enter the body. In this drug-induced state of radical opening to alterity, “[s]trangeness and strangerness become ordinary, everyday occurrences” (9). Does this condition mark a gesture towards unconditional hospitality? Nancy suggests that his identity is entirely informed by his immune status; what would it mean to reconceptualize identity as a measure of the degree of immunity we possess and mobilize in response to a chronic proliferation of intruders? Nancy traces out an originary and unwavering strangeness that is not solely found within, but is actually constitutive of, the self: “an immune system that is at odds with itself, forever at cross purposes, irreconcilable” (10). Can a discussion of a physical grafting of an organ formerly belonging to an other instructively demonstrate a radical opening of the self to otherness, though the two may, on some level, forever remain irreconcilable? Nancy does suggest that reconciliation could take place, and suffering could be reduced, if only we could receive the intruder graciously and without resistance: “the suffering is the relation of the intrusion and its refusal” (11). It is precisely for this reason that Nancy’s text is so important: he speaks of a seemingly “natural” biological response of the self’s violent attack on the intruding Blacker 12 other, only to later insist that there can be no ideological differentiation between the two. Nancy’s discussion radically overturns any notions of distance and incommensurability between “self” and “other,” whether within community or without. The béance brought forth by L’Intrus announces a radically new conception of subjectivity within which there can be no division between “self” and “other.” The two are intricately woven together through a surgical grafting, and in this way, the “self” not only permanently dwells with the “other,” but both are altered and identity arises out of and is wholly determined by the in-between: “[t]he intrus is no other than me, my self” (13). Blacker 13 Preliminary Works Cited Adamek, Philip M. “The Intimacy of Jean-Luc Nancy’s L’Intrus.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 189-201. Belk, Russell W. “Me and Thee Versus Mine and Thine: How Perceptions of the Body Influence Organ Donation and Transplantation.” Organ Donation and Transplantation: Psychological and Behavioral Factors. Ed. James Shanteau and Richard Jackson Harris. Washington: American Psychological Association, 1992. Culler, Jonathan. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism. London: Routledge, 1983. Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference. Trans. Alan Bass. London: Routledge, 1978. Derrida, Jacques. Dissemination. Trans. Barbara Johnson. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981. Derrida, Jacques. Glas. Trans. John P. Leavey, Jr. and Richard Rand. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. Derrida, Jacques. Given Time: I. Counterfeit Money. Trans. Peggy Kamuf. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992. Derrida, Jacques. Aporias: dying—awaiting (one another at) the “limits of truth.” Trans. Thomas Dutoit. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993. Derrida, Jacques. The Gift of Death. Trans. David Wills. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995. Derrida, Jacques. “Hostipitality,” Trans. Barry Stocker and Forbes Morlock. Angelaki: journal of the theoretical humanities 5.3 (2000): 3-18. Derrida, Jacques. On Touching—Jean-Luc Nancy. Trans. Christine Irizarry. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005. Egginton, William. “The Sacred Heart of Dissent.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 109-138. Fox, Renee C. and Judith P. Swazey, Spare Parts: Organ Replacement in American Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Freund, Peter and Meredith McGuire. Health, Illness, and the Social Body: A Critical Sociology. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1991. Blacker 14 Fynsk, Christopher. “L’Irréconciliable.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 23-36. Hanson, Susan. “The One in the Other.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 203-209. Kamuf, Peggy. “Béance.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 37-56. Komesaroff, Paul A., ed. Troubled Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Postmodernism, Medical Ethics, and the Body. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995. Kristeva, Julia. Strangers to ourselves. Trans. Leon Roudiez. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. Lock, Margaret. Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death. Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2002. Nancy, Jean-Luc. The Inoperative Community. Trans. Peter Connor et al. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991. Nancy, Jean-Luc. Being Singular Plural. Trans. Robert D. Richardson and Anne E. O’Byrne. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000. Nancy, Jean-Luc. “Is Everything Political? (a brief remark).” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 15-22. Nancy, Jean-Luc. L’Intrus. Paris: Galilée, 2000. Nancy, Jean-Luc. “L’Intrus.” Trans. Susan Hanson. CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 1-14. O’Byrne, Anne. “The Politics of Intrusion.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 169-187. Palumbo-Liu, David. “The Operative Heart.” CR: The New Centennial Review 2.3 (2002): 87-108. Randhawa, Gurch. “The ‘Gift’ of Body Organs.” Social Policy and the Body: Transitions in Corporeal Discourse. Ed. Kathryn Ellis and Hartley Dean. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000. 45-62. Ross, Lainie Friedman. “Solid organ donation between strangers.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. Boston: 30.3 (Fall 2002). Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Loic Wacquant, eds. Commodifying Bodies. London: Sage Publications, 2002. Blacker 15 Schrift, Alan D., ed. The Logic of the Gift: Toward an Ethic of Generosity. New York: Routledge, 1997. Serres, Michel. The Parasite. Trans. Lawrence R. Schehr. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. Sharp, Lesley A. “Organ Transplantation as a Transformative Experience: Anthropological Insights into the Restructuring of the Self.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 9.3 (September, 1995). Shershow, Scott Cutler. The work and the gift. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005. Žižek, Slavoj, Eric L. Santner and Kenneth Reinhard. The Neighbor: Three Inquiries in Political Theology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.