Property – Billman, Spring 2003

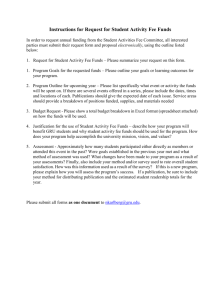

advertisement