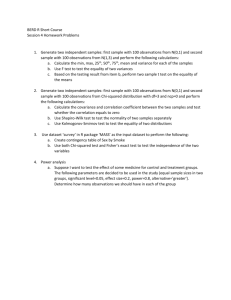

Read the case submission - Equality and Human Rights Commission

advertisement

C1/2013/1283 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE ADMINISTRATIVE COURT BETWEEN:THE CROWN ON THE APPLICATION OF BRACKING & OTHERS Appellants - and – SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK & PENSIONS Respondent -andTHE TRUSTEES OF THE INDEPENDENT LIVING FUND Interested Party - and THE EQUALITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Intervener _____________________________________________________________ INTERVENTION ON BEHALF OF THE EHRC _____________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION 1. The Equality & Human Rights Commission (EHRC) intervened in this case at first instance. On 24 April 2013, Blake J granted permission but rejected the substantive application for judicial review of the Respondent's decision to close the Independent Living Fund (ILF). 1 2. The claim is brought on the basis (in part) that in the process by which it has addressed the decision, the Respondent breached the public sector equality duty now contained in s149 Equality Act 2010 ("EqA 2010"). 3. This aspect of the claim raises significant issues of wider public importance. The Commission is concerned: a) that the Respondent failed properly to address the statutory equality needs in the context of a major changes to the structure of provision to enabled disabled people to live independently; a change which is likely to affect their rights protected by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2006 ("UNCRPD"). and b) that the learned judge did not correct this error. In particular, he glossed over the absence of evidence that the Minister had conducted any focused rigorous thought ("due regard") to equality implications of her decision for disabled people, because the context was 'levelling down' of provision for some disabled people to that which others could in future expect, which he regarded as a relevant countervailing consideration (decision [53v], AB/1/53). 4. It is important that this error of approach should be corrected. As Davis LJ (as he then was) observed in Meany v Harlow DC [2009] EWHC 559 Admin at [78]-[79] there is a distinction between the question of whether there has been due regard to equality; and the question of whether - if there has - the decision is a rational one having regard to relevant countervailing considerations. 5. In any event, the decision under challenge was not ever about redistributing a ring- fenced budget for the needs of some disabled people among a wider group; it was about removing the ring-fenced budget for disabled people's independence, initially distributing an equivalent amount among local authorities as part of their general 'pot' to spend as they saw fit (including on the needs of non-disabled people); and - from 2015 - removing such funding altogether. The judge failed properly to address whether the Minister herself had identified the potential implications of such a decision for the 2 ability of disabled people to live independently, and addressed the need to advance equality in relation to that opportunity in a structured, rigorous and informed way as required by s149(1)(b) EqA 2010. 6. The Commission considers that the learned Judge erred by implicitly suggesting that the public sector equality duty had little if any application in such a context; and that the (wholly unspecific and inadequate) regard given to the obvious, and serious, implications of the decision, was therefore adequate. He also incorrectly distinguished the approach taken by this Court in Burnip v Secretary of State for Work & Pensions [2012] EWCA Civ 629. 7. The Commission's remit as the expert regulator in this field is to assist the Court as to the correct legal approach to the public sector equality duty. The Commission's submissions address the following topics: a) The role of the EHRC; b) Overview of the Commission's approach; c) Relevant legal background d) The statutory purpose of the public sector equality duty; f) The correct interpretation of s149(1) EA 2010, and the effect of s149(3), (4), (6) and s158 EA 2010 on the interpretation of s149(1)(b). g) The interaction of the public sector equality duty and the duty to consult. h) Relevant Commission guidance. i)The relationship between the public sector equality duty and the UN Convention on the Rights of Disabled Persons; j) Some observations on the approach of the judge below. 3 THE ROLE OF THE EHRC IN RELATION TO THE PUBLIC SECTOR EQUALITY DUTY 8. The Commission was established under the Equality Act 2006 ("EqA 2006"): see s.1. The Commission has been accredited with “A” status by the International Co-ordinating Committee which assesses and reviews the compliance with the UN's Paris Principles for National Human Rights Institutions. It thus has formal status with the Human Rights Council and human rights treaty bodies of the United Nations and plays an active role in UN treaty monitoring of the UK. The Paris Principles (paragraph 3(c)) require the Commission, as the UK's national human rights institution "to promote and ensure harmonisation of national legislation with the international human rights instruments to which [the UK] is a party and their effective implementation." 9. The Commission has statutory duties, inter alia, to promote understanding of the importance of equality and diversity, encourage good practice in relation to equality and diversity, and to enforce the equality enactments: s.8(1), EqA 2006. It also has statutory duties to promote understanding of human rights principles, to encourage good practice in relation to human rights issues and to encourage public bodies to comply with section 6 Human Rights Act 1998: s9(1) EqA 20061. The Commission has power under s30 EqA 2006 intervene in legal proceedings if it appears to it that "the proceedings are relevant to a matter in connection with which the Commission has a function.” 10. The EHRC has a particular interest in the correct application of the public sector equality duty, contained in s149 EqA 2010, because that duty is (as Arden LJ observed in Elias v Secretary of State for Defence [2006] 1WLR 3213 at [274]) "an integral and important part of the mechanisms for ensuring the fulfilment of the aims of anti-discrimination legislation". In the same case, Arden LJ said (at [274]) `"Human rights" for this purpose means both the Convention rights within the meaning of section 1 `Human Rights Act 1998 and other human rights (s9(2) 2006 Act) 1 4 "it is not possible to take the view that [a decision-maker's] non-compliance with the [public sector equality duty] was not a very important matter. In the context of the wider objectives of anti-discrimination legislation, [the public sector equality duty] has a significant role to play". 11. The current public sector equality duty in s149 EqA 2010 was preceded by three separate duties, concerning race, sex and disability, set out in s71 Race Relations Act 1976 as amended (RRA), section 76A Sex Discrimination Act 1976 (SDA), and section 49A Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA). The Commission intervened in some of the early cases concerning these predecessor public sector equality duties, and its interventions have been regarded as useful2. The Commission also recently intervened in R (South West Care Homes) v Devon County Council [2012] EWHC 2967 (Admin), which related to setting the 'ordinary cost of care' normally payable for residential care 2 These cases include, notably: a. R(C) v Secretary of State for Justice [2008] EWCA Civ 882, [2009] QB657 (concerning secure training centres, which established that failure to comply with section 71 RRA was a substantial, and not mere procedural failing.) b. R (Brown) v Secretary of State for Work & Pensions & Secretary of State for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, EHRC intervening [2008] EWHC 3158 (Admin), [2009] PTSR1506 (the ‘post office closures’ case, in which the Divisional Court drew extensively on the Commission’s formulation of the legal principles governing the application of the disability equality duty (paragraphs [90]-[96]), which formulation was recently approved by the Court of Appeal in R(Greenwich Community Law Centre) v London Borough of Greenwich [2012] EWCA Civ 496; [2012] All ER (D) 157; c. R(Baker) v Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government [2008] EWCA Civ 141 (2008) LGR 239 (which concerned section 71 RRA and the grant of planning permission in the context of policy guidance concerning gypsies). d. R(Kaur & Shah) v London Borough of Ealing, EHRC intervening [2008] EWHC 2062 (Admin), in which Moses LJ (sitting as an Administrative Court judge) made important observations as to circumstances in which the concept of promoting of equality must include recognition of difference, approving submissions made on behalf of the EHRC. e. R(Harris) v London Borough of Haringey [2010] EWCA Civ 403; [2011] PTSR 931, in which the Court of Appeal ruled on the application of the race equality duty in the context of a planning decision intended to regenerate a racially diverse area for the benefit of all its residents. 5 home provision. The court in that case approved the EHRC's observations on the interrelationship between the PSED and the positive obligations under the UNCRPD. 12. The Commission has (as its predecessors had) the function of publishing advice and guidance under sections 13 and 14 EA 2006. Such guidance on the operation of the public sector equality duties has been cited with approval in a number of cases, including by the Divisional Court in R(Brown) v Secretary of State for Work & Pensions [2008] EWHC 3158 (Admin), [2009] PTSR 1506 at [119-120]: "[119] ... we accept the following propositions on the status of the Code [of practice published by the Disability Rights Commission]. First, a public authority must take the Code into account when considering disability equality issues. If it decides to depart from it, cogent reasons must be given and they must be convincing: see Khatun at para 47 per Laws LJ. However, we also agree ... that there are no higher positive duties to comply with the Code ... [120] Secondly, if a breach of the [public sector equality duty] is alleged and it appears to a court that relevant guidance given by the Code [of practice given by the Disability Rights Commission] has been ignored, departed from, misconstrued or misapplied without cogent reason, then that may be a powerful factor that leads the court to conclude that there was a breach of statutory duty by the public authority. Thirdly, it would be for the public authority to explain clearly and convincingly the reasons for the lapse". 13. The Commission has recently published Technical Guidance on the PSED, which is relevant to and will be of assistance in this case, and which is appended to these submissions. There are a number of respects in which it appears that there have been departures from that Guidance, without any recognition or explanation of that fact by the Respondent. OVERVIEW OF THE COMMISSION'S POSITION 14. The evidence before the Court did not demonstrate that the decision was adequately informed by structured, rigorous analysis of its likely impact on the equality needs identified in s149(1)(a) and (b) EqA 2010 as to impact of what was proposed on the human rights of those affected to live independently in the community (as the law requires: see per Pill LJ in Harris v London Borough of Haringey [2010] EWCA Civ 703 at 6 [40], "due regard" to the statutory equality needs means analysis of the material available to the decision maker "with the specific statutory considerations in mind"). 15. There was no evidence before the judge of anything more than 'name-checking' equality or independence; and no evidence of any rigorous analysis was undertaken in relation to how to avoid these effects which - as a matter of law - could only be tolerated if the only alternative was a truly disproportionate burden on the state (see AH, cit post). 16. Although this case concerns two limbs of the public sector equality duty: the duty to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination (including indirect discrimination) under s149(1)(a) EqA 2010 and the duty to have due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity for various protected groups under s149(1)(b), it is the latter which is to the fore, particularly when it is appreciated that the opportunity in question is that defined in Article 19 UNDRPD "to live in the community with choices equal to others ..." 17. The learned judge failed properly to appreciate and apply the structure of the second limb of the public sector equality duty, as set out in s149(1)(b) EqA 2010. Whilst it is modelled on the predecessor duties, it is not identical to them. In particular, s149(1)(b) refers to the need to 'advance' equality of opportunity, not merely to 'promote' it. This is a difference which Professor Sir Bob Hepple QC (former Master of Clare College Cambridge and the country's leading academic authority on equality law) considers to be material (see "Equality, the New Legal Framework" (Hart Publishing, 2011) at p135). Professor Hepple's perception of a more positive formulation accords with the positive obligations under the UNCRDP to 'take effective and appropriate measures to facilitate full enjoyment of [the Article 19] right ...'. 18. Moreover, unlike the predecessor public sector equality duties in the RRA, SDA and DDA, s149(1)(b) EqA 2010 is not free-standing. The measures which it involves are elaborated and explained in sections 149(3), (4) and (6). The judgment does not explain how the analysis of equality can be aid to comply with s149(1)(b) EqA 2010 read so as to give effect to s149(3), (4) and (6). 7 19. There is an important practical issue in this case as to the interaction of the public sector equality duty and the public law duty to consult. At first instance, the Respondent suggested, in the Summary Grounds of Resistance (paragraphs 54 and 69, AB/1/9/100 & 103) that if the Claimants are right that equality should have been conscientiously considered before the conclusion of the consultation, and that consultees should have been informed of that thinking: "(54) ... then the result would be required to include a full equality impact assessment in every consultation ..." ... (69) The implication ... would be that formal equality impact assessment documents would invariably require to be completed before or at the same time as consultations ..." 20. This submission is not right. It is based on a misapprehension as to the technical requirements and statutory purpose of the public sector equality duty, and the role which 'formal equality impact assessment documents' play (and do not play) in compliance with the duty. 21. The Defendant's apparent understanding of the legal position both overstates the importance of an EIA and understates the importance of focused evidence gathering, to comply with the state's obligations under Article 31 UNCRPD. 22. The Commission, as the UK's National Human Rights Institution, respectfully draws the Court's attention to the learning as to the relevance of the UNCRPD to the issues in this application, including the recent Court of Appeal authority of Burnip, which (see [69] below), the judge at first instance incorrectly sought to distinguish. 23. The Commission's submissions below set out the correct analytical approach to these issues. The Commission deprecates any mechanistic or formulaic approach to performance of the public sector equality duty, and draws the court’s attention to how the equality duty requires due regard to the equality implications of decisions equality to be brought into the mainstream of public body decision-making, including the 8 interaction between the public sector equality duty and the duty to consult; by reference to its new Technical Guidance on the PSED; and by reference to the UNCRPD. THE LEGAL BACKGROUND Relevant sections of the Equality Act 2010 24. Section 149 EqA 2010 provides (so far as is material): “(1) A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to – (a) Eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act; (b) Advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it; (c) Foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it. (2) ... (3) Having due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it involves having due regard, in particular, to the need to – (a) remove or minimise disadvantages suffered by persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are connected with that characteristic; (b) take steps to meet the needs of persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are different from the needs of persons who do not share it; (c) encourage persons who share a relevant protected characteristic to participate in public life or in any other activity in which participation by such persons is disproportionately low; (4) The steps involved in meeting the needs of disabled persons that are different from the needs of persons who are not disabled include, in particular, steps to take account of disabled persons’ disabilities (5) ... (6) Compliance with the duties in this section may involve treating some persons more favourably than others; but that is not to be taken as permitting conduct that would otherwise be prohibited by or under this Act. 9 (7) The relevant protected characteristics are – ... Disability ... " 25. Section 149(6) EqA 2010 should be read in conjunction with s158 EqA 2010. S158 provides, so far as material: "(1) This section applies if a person (P) reasonably thinks that a) persons who share a protected characteristic suffer a disadvantage connected with that characteristic, b) persons who share a protected characteristic have needs that are different from the needs of persons who do not share it, or c) participation in an activity by persons who share a protected characteristic is disproportionately low. (2) This Act does not prohibit P from taking any action which is a proportionate means of achieving the aim of a) enabling or encouraging persons who share the protected characteristic to overcome or minimise that disadvantage, b) meeting those needs, or c) enabling or encouraging persons who share the protected characteristic to participate in that activity. ..." STATUTORY PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE PSED 26. The public sector equality duty is intended to guard against the creation or continuation of policies and practices which, if their impact remains unexamined, may disadvantage particular sections of our communities. The duty was introduced to remedy the previous position in which 'regrettably little' thought has been given to the interests of disabled people in policy formation (Brown (cit. sup.) at [30]) and to 'avoid the inadvertent' creation of disadvantage (R(Luton Borough Council & Ors) v Secretary of State for Education [2011] EWHC 217 (Admin) at [115]), by requiring public authorities to give advance consideration to the likely or possible equality impact of their activities, and to consider whether those activities can be performed in a way which addresses specific identified equality policy objectives (described in the statutes as 'needs'). 27. The public sector equality duty is also intended to focus recognition on the need in some circumstances for adjustment of policies and structures and provision of specialist 10 allowances and services to advance genuine equality of opportunity or outcome, even if that means treating some members of some disadvantages groups apparently more favourably: "there is no dichotomy between the promotion of equality and cohesion and the provision of specialist services to ... a minority" [which can be] "anti-discriminatory and further the objectives of equality and cohesion. I can do no better than to conclude this judgment ... by quoting the chairman of the Equalities Review in the final report Fairness and Freedom, published in 2007: "An equal society protects and promotes equality, real freedom and substantive opportunity to live in the ways people value and would choose so that everyone can flourish. An equal society recognises people's different needs, situations and goals and removes the barriers that limit what people can do and can be"". (per Moses LJ in the context of specialist services for black minority ethnic victims of domestic abuse, R(Kaur & Shah) v London Borough of Ealing [2008] EWHC 2062 (Admin) [55] and [58], emphasis added). 28. The Commission wishes to emphasise the broad scope of application of the public sector equality duty. It arises - perhaps most pertinently - when a policy or new way of delivering a service is under review, including reconfiguring or restructuring expenditure which would have or which may (on further examination) have an impact on the statutory equality needs in relation to persons with a particular protected characteristic. 29. It does not matter if the service being reconfigured does not affect all people with a particular protected characteristic. The issue to which 'due regard' must be given is the impact of the actual decision under consideration upon equality of opportunity (etc) for disabled people. 30. If - for example - a decision were taken to redistribute a ring-fenced fund for independent living from some disabled people among a wider group of disabled people, it might be thought that the impact of the decision on equality of opportunity for disabled people compared with non-disabled people would be broadly neutral. But if the decision is to remove a ring-fenced fund for independent living for some disabled 11 people, to be applied to whatever needs a local authority thinks fit, one can see at once that the implications for equality of opportunity are very different, and almost certainly adverse and severe. That is the position here, where the proposal under consideration was to close the Independent Living Fund and to distribute an equivalent sum (in the first year) to local authorities, in an entirely unringfenced way. 31. That was a decision in which the particular needs and aspirations of a group consisting of disabled people, a deeply disadvantaged minority, and to whose needs - as Aikens LJ said in Brown - 'regrettably little' attention has been paid in the past, have been subsumed to the 'wider public interest' of the majority: the very context in which the public sector equality duty was intended to make a difference to the policy-making approach; to ensure that policy changes advance equality of opportunity if possible; and in any event, wherever possible, do not - however inadvertently - diminish it in unnecessary ways. As Holman J observed in the Luton Borough Council case (cit. sup) at [115], the purpose of the PSED is to "avoid the 'inadvertent'". 32. Like other requirements of public law, such as consultation, giving 'due regard' to equality requires an active and conscientious frame of mind. Whether 'due' - ie sufficient - regard to the statutory equality needs has been given in the circumstances is a matter for the Court to decide for itself (R(Meany) v Harlow District Council [2009] EWHC 559 (Admin) at [72] and [78]-[79]. Where a decision will affect vital interests of large numbers of people - including (potentially) the right to live independently in circumstances of their own choice - the 'regard' to be given to the statutory equality needs is obviously correspondingly very high: see R(Hajrula) v London Councils [2011]EWHC 448 Admin at [68]. THE CORRECT INTERPRETATION OF S149(1) EQUALITY ACT 2010 AND THE EFFECT OF SECTION 149(3), (4) AND (6) AND S158 ON ITS INTERPRETATION 33. Although the current public sector equality duty is based on the predecessor duties in the race, sex and disability predecessor legislation, the language was refined and expanded when EqA 2010 was brought into force. 12 34. The first major expansion brought about by s149 EqA 2010 is that the duty to give ‘due regard’ to equality now covers all equality strands. The second is that the statutory language makes it much clearer what giving ‘due regard’ to each of the statutory equality needs involves, and in particular, gives greater guidance as to what is meant by, and involved in, 'giving due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity'. 35. The duty to give due regard to the three broad, linked but distinct statutory equality needs identified separately and sequentially in s149(1)(a), (b) and (c) EA 2010 goes beyond the need to avoid formal non-discrimination in comparison with some established ‘norm’. (That was so even under the old single-strand formulations of the public sector equality duty. As Dyson LJ - as he then was - explained (in the context of the race duty) in his judgment in R(Baker) v Secretary of State for the Environment [2008] EWCA (Civ) 141 at [30]: “… promotion of equality of opportunity … will be assisted by, but is not the same thing as the elimination of racial discrimination … the promotion of equality of opportunity is concerned with issues of substantive equality and requires a more penetrating consideration than merely asking whether there has been a breach of the principle of non-discrimination…” (emphasis added). 36. The higher courts have consistently emphasised the importance of a realistic and purposive approach to the performance of the public sector equality duty (see in particular Brown at [90]-[96]). The caselaw illustrates that a public authority will rarely if ever be able to demonstrate compliance with them in relation to a major policy decision simply by averring that it has kept `equality issues’ in mind at some point in the course of the policy-making process (R(Chavda) v London Borough of Harrow [2007] EWHC 3064 (Admin) at [40]). As the Court of Appeal decided in Harris v London Borough of Haringey (cit sup) at [40], the Court must be able to find evidence of analysis of the material available to the decision maker "with the specific statutory considerations in mind". The duties must be brought adequately to the attention of decision-makers (Rahman at [57]), and in examining whether there has been compliance with the public sector equality duty, the Court must be able to discern that due regard has been had to the specific elements of the duty insofar as 13 they are relevant to the issue in hand (Rahman at [31]), R(Hurley & Moore) v Secretary of State for Business [2012] EWHC 201 (Admin) at [96]). 37. The public sector equality duty is a duty of consideration not result. However, the equality goals are not ‘mere relevant considerations’: they are described, in the statutory language, as ‘needs’. The public sector equality duty may not be a duty of result, but it is a duty to formulate policy with an intended direction of travel and with the potential equality consequences of a decision well in mind. 38. The current public sector equality duty also differs from the predecessor duties in that it contains expansive or explanatory sections which expand upon what is meant by sections 149(1)(b) and (c) EqA 2010. Section 149(3) EqA 2010 sets out, for the first time, a helpful expanded definition of what is involved in 'having due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity' between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons in practice. The intention of the explanatory sections is to ensure that public bodies address their minds to what is "involved" in advancing equality of opportunity when purporting to address the need to do so. 39. Subsections 149(3)(a) and (b) state explicitly that giving due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity "involves" - identifying the causes of inequality and disadvantage associated with a protected characteristic, - addressing the questions of how those disadvantages can be removed in the performance of the public function, including the active steps needed to address the different needs of those with protected characteristics from those who do not share them; - considering those findings having due regard to the need to advance (rather than hinder) equality of opportunity between such people. 14 40. Section 149(4) EA 2010 further specifies that the steps involved in meeting the needs of disabled persons that are different from the needs of persons who are not disabled include, in particular, steps to take account of disabled persons' disabilities. 41. Section 149(6) EA 2010 reminds decision-makers and courts that compliance with the duties encompassed in s149(6) may involve treating some people more favourably than others, so far as is permitted by or under the remainder of the EA 2010. This section should be read with s158 EA 2010 which specifically permits - proportionate positive action to enable or encourage people who share a protected characteristic to overcome disadvantages connected to it (s158(1)(a) and 158(2)(a)). - proportionate positive action to meet the needs of persons who share a protected characteristic who have needs that are different from the needs of person who do not share it. 42. These explanatory sections emphasise the structured and rigorous approach which is involved in having due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity where a particular public sector decision may have an impact upon it. Unless an authority can demonstrate that it understands these disadvantages associated with a characteristic in a context, and has addressed 'in substance and with rigor' what could be done to redress those disadvantages, it is unlikely to be able to persuade the court that it has given 'due regard' to the need to advance equality of opportunity. This is really a specific and focused statutory application to equality of the Tameside requirement for a decision-maker to address its mind to the problem before it in an informed way. Without doing this, a decision-maker will not be able to give `due regard' to equality (as the statute requires), properly informed in relation to relevant considerations. 43. The explanatory sections mean that, in order to comply with s149(1)(b) EA 2010: (a) the decision maker must have identified disadvantages which persons with obvious relevant protected characteristics have connected with that 15 characteristic, if a potential decision under consideration may have an impact on increasing or diminishing those disadvantages (s149(3)(a) EA 2010). (b) the decision maker must address how inequalities of opportunity which arise as a result of those disadvantages may be removed or minimised, so as to advance equality of opportunity, by the performance of the public function (s149(3)(a) EA 2010); (c) consideration of the removal or minimisation of identified disadvantage should include consideration of the need to take steps to meet the different needs of people with protected characteristics (s149(3)(b) EA 2010, s149(4) EA 2010). (d) the consideration of removal or minimisation of disadvantage may include considering whether proportionate positive steps may be taken for people with particular protected characteristics which are not taken for other people, in order to help them to overcome or minimise those disadvantages or meet particular needs (s158(1)(a) and 158(2)(a), s158(1)(b) and 158(2)(b), s149(4) EA 2010). 44. The learned judge did not address these sections at all in explaining how he came to the conclusion that the Respondent had demonstrated 'due regard' to the need to advance equality of opportunity for disabled people to live independently. 45. The judicial role in determining whether there has been compliance with the public sector equality duty is to consider whether the duty has been performed in substance, not in form. The presence of some ministerial statements regarding equality and a division of a department named 'Personalisation and Independence' is no more relevant than whether 'an EIA' has been 'performed'. This was clearly explained by Moses LJ in Kaur & Shah cit. sup: [22] “The jurisprudence … reinforces the importance of considering the impact of any proposed policy before it is adopted as part of the significant role of [the public sector equality duty] in fulfilling the aims of anti discriminatory legislation [citing Elias]… In considering the impact, the authority must assess the risk and 16 extent of any adverse impact and the ways in which such risk may be eliminated”: [23] The need for advanced consideration must be distinguished from the use of such impact assessments for what Sedley LJ described as a rearguard action following a concluded decision (see R (BAPIO and another) v Secretary of State for the Home Department and the Secretary of State for Health [2007] EWCA Civ 1139 paras 2 and 3). What is important is that a racial equality impact assessment should be an integral part of the formation of a proposed policy, not justification for its adoption [emphasis added]. [24] The process of assessments should be recorded (see Stanley Burnton J at first instance in BAPIO [2007] EWHC 199 (QB)). Records contribute to transparency. They serve to demonstrate that a genuine assessment has been carried out at a formative stage. They further tend to have the beneficial effect of disciplining the policy maker to undertake the conscientious assessment of the future impact of his proposed policy, which s 71 requires. But a record will not aid those authorities guilty of treating advance assessment as a mere exercise in the formulaic machinery. The process of assessment is not satisfied by ticking boxes. The impact assessment must be undertaken as a matter of substance and with rigor (see R (Baker and others) v Secretary of State and the London Borough of Bromley ...)". THE INTERACTION OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR EQUALITY DUTY AND THE DUTY TO CONSULT 46. The public sector equality duty requires a decision-maker to address the statutory equality needs 'in substance, with rigour and an open mind' at a formative stage of the decision-making process, to avoid the creation of 'inadvertent' (because unappreciated or insufficiently anticipated) disadvantage. Article 31 UNCRPD requires policies which will have an impact on the object of promoting disability equality to be formulated on the basis of 'appropriate information'. 47. How does one collect 'appropriate information' on the impact of a policy on persons likely to be affected by it, particularly if they are people whose life experiences and practical needs are likely to differ substantially from the 'norm'? An obvious means of doing so is by consulting them. It is, therefore, very likely that a deficiency in consultation in the context of a decision with potential equality impact will coincide and be indicative of a breach of the public sector equality duty. That, indeed, is reflected in the caselaw: see (for example) 17 - the EHRC case (cit. sup) at [49]: "... matters which were important to the [public sector equality duty] were not considered ... the note contains the assertion that health issues and disability should also be considered but no suggestion that it was. The evidence demonstrates that no consultation was undertaken with interested bodies prior to the adoption of [the policy] ..." - the Luton case (cit. sup) at [113-114]: "... I am simply not satisfied that any regard was had to the relevant duties, let alone rigorous regard. The tie-in is, of course, with the lack of consultation. Different claimants have emphasised to me schools of particular disability ... relevance in their areas. The point is that if only the Secretary of State had consulted with them they would have been able (if they wished) to highlight those special equality considerations to him". 48. It is not only in cases of complete absence of consultation on relevant issues where the Courts can and will infer breach of the public sector equality duty. There is also likely to be inadequate regard to the statutory equality needs in circumstances where deficiencies in consultation lead to deficiencies in the gathering and consideration of relevant information. See for example R(JM) v Isle of White Council [2011] EWHC 2911 (Admin), in which Lang J held that the local authority had failed to comply with the public sector equality duty 'principally' because it did not gather the information required to do so properly, owing to deficiencies in the consultation (see [118]-[119], [122], [126], [140]). THE EHRC'S TECHNICAL GUIDANCE ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR EQUALITY DUTY 49. The Commission and its predecessor bodies have produced statutory and non-statutory guidance on public sector equality duties. The most recent, "Technical guidance on the Public Sector Equality Duty in England" was published under s13 Equality Act 2010 on 15 January 2013 and is appended to these submissions. The purpose of the guidance is to explain how public authorities can meet the requirements of s149 EA 2010, and it is admissible in Court proceedings. 18 50. The Commission draws particular attention to Chapter 5 of this guidance "complying with the general equality duty in practice", and in particular, paragraphs 5.15-5.36 "Ensuring a sound evidence base" and "Engagement". 51. The Commission respectfully invites the Court to adopt the approach adopted by Moses LJ in Kaur & Shah at [22] and the Divisional Court in Brown at [120] and to use the Commission's guidance to structure its enquiry as to whether there has been due regard to the statutory equality needs on the facts of this case. THE INTERACTION OF THE PUBLIC SECTOR EQUALITY DUTY AND THE UN CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 2006 52. Proper performance of the public sector equality duty is a means by which the United Kingdom can give effect to its obligations under Article 1 of the UNCRPD to 'promote' equal opportunities for disabled people. If there is doubt as to whether there has been 'due' regard to the statutory equality needs, it must be interpreted in a way which gives effects to those obligations. (The most material to this case are set out in an Annex to this submission). 53. Article 1 UNCRPD emphasises the positive obligations inherent in avoiding discrimination against disabled people (and therefore the ambit of that which must be considered to avoid such discrimination). It states that discrimination includes denial of reasonable accommodation (ie positive steps) to remove barriers which have the effect of nullifying enjoyment on an equal basis with others of human rights. Those rights include that contained in Article 19 and "recognised by States Parties to this Convention" (including the UK) "to live in the community with choices equal to others ... [and] to choose their place of residence ... on an equal basis with others and ... not [to be] obliged to live in a particular living arrangement". 54. The Respondent in the present case appeared to accept that the effect of the decision to close the ILF and to disperse funds to local authorities on a non-ring fenced basis may be 19 to remove from some recipients of ILF money the ability to live independently in the Community. That being so, the PSED should be interpreted so that a high standard of scrutiny should be expected of such a measure, since "the protection and promotion of human rights of persons with disabilities must be taken into account in all policies and programmes", and since the UK must "refrain from engaging in any act or practice that is inconsistent with the Convention ..." and public authorities must act in conformity with it. 55. As the Court of Appeal recently confirmed in Burnip (cit. sup., per Maurice Kay LJ at [19]-[22]), the relevant provisions of the UNCRPD inform the correct approach to domestic human rights and equality legislation. Maurice Kay LJ's observations were based on observations of the Grand Chamber of the ECtHR that specialist international instruments not only may but 'must' be taken into account when interpreting human rights. They are therefore material in deciding whether a public authority has given due regard to the need - which is an international law obligation - to advance equality of opportunity (and therefore to promote protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons with disabilities. 56. The court not only may, but must, take the relevant provisions of the UNCRDP into account when interpreting the domestic legislation, and in particular, when assessing whether a public authority has complied with the public sector equality duty and Articles 8 and Article 14 ECHR. The requirement to do so is enshrined both in national and ECtHR caselaw3. 57. Moreover, the fact that the UK government is a signatory to the UNCRPD is relevant in determining when it is proportionate to make a decision which (directly or indirectly) discriminates against disabled people. That is not to seek - impermissibly - to give an unincorporated treaty direct effect in domestic law4. Rather, it is recognition of the long-standing public law principle that a public authority may not depart from its public 3 The advocate-general also relied upon the UNCRPD her opinion in Jette Ring v Dansk almennyttigt Boligselskab DAB (CaseC-335/11) in proposing a broad construction of the duty of reasonable accommodation for disabled persons in the EU's Framework Directive 2000/78/EC, 6 December 2012. 4 cf Laws LJ in R(MA & Ors) v Secretary of State for Work & Pensions [2013] EWHC (Admin) * at *. 20 policy pronouncements without clearly recognising that it is doing so and articulating a reason for it. 58. In AH v West London Mental Health Trust & Secretary of State for Justice [2011] UKUT 74, the UT, presided over by Lord Justice Carnwarth (as he then was, now Lord Carnwarth JSC), described the relevance of the UNCRDP thus: “[15] The [UN]CRPD prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities and promotes the enjoyment of fundamental rights for people with disabilities on an equal basis with others ... [ratification history set out]. [16] The [UN]CRPD provides the framework for Member States to address the rights of persons with disabilities. It is a legally-binding international treaty that comprehensively clarifies the human rights of persons with disabilities as well as the corresponding obligations on state parties. By ratifying a Convention, a state undertakes that wherever possible its laws will conform to the norms and values that the Convention enshrines. [emphasis added] ... [22] ... article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (reinforced by article 13 of the [UN]CRPD) requires that a patient should have the same or substantially equivalent right of access to a public hearing as a non-disabled person who has been deprived of his or her liberty, if this article 6 right to a public hearing is to be given proper effect. Such a right can only be denied a patient if enabling that right imposes a truly disproportionate burden on the state [emphasis added]. The European Court of Human Rights has emphasised the need for special consideration to be given to the rights of particularly vulnerable groups such as the mentally disabled (see eg Kiss v Hungary (App no 38832/0, judgment 20 May 2010 para 42)).” This reasoning was approved and adopted by the Court of Appeal in Burnip (cit. sup). 59. Thus, a decision taken without adequate scrutiny of the positive obligation to protect the right of disabled people to live in the community with choices equal to others is irrational. A high-level national government decision which, not only fails to fulfil, but significantly moves away from the fulfilment of a binding international law obligation to 21 protect the human rights of a disabled person to live independently; which is taken without any recognition that it is a departure from those standards; and without any explanation for the departure from them is irrational and inevitably breaches the public sector equality duty. 60. The public sector equality duty to give "due regard" to the need to "advance" equality of opportunity implies an obligation upon a decision-maker adequately to inform itself as to the prospective impact of a decision on equality of opportunity for persons with disabilities, identifying first which opportunities the decision might affect; what the impact of the decision upon access to them might be; and what steps if any can be taken to address relevant adverse impacts or to promote positive ones. 61. That duty to make a decision on the basis of adequate relevant enquiry and information is buttressed by the obligation in Article 31 UNCRPD for states party to "collect appropriate information" including research data to "enable them to formulate and implement policies to give effect to the UNCRPD". There is no evidence of any such data collection in this case. 62. A policy which adversely affects rights protected by the UNCRPD and which is formulated in the absence of appropriate information is highly likely to breach the duty of enquiry in the PSED. That is particularly so when the duty is interpreted through the 'clarifying' prism of the UNCRPD and the obligation undertaken by the UK in ratifying it that "wherever possible its laws will conform to the norms and values of the Convention" and that there will only be denial of rights protected by Article 8 ECHR and by the UNCPRD "if enabling that right imposes a truly disproportionate burden on a state" (per Lord Carnwarth in AM, cit sup). THE APPROACH OF THE JUDGE AT FIRST INSTANCE 63. It is not the purpose of this submission to 'enter the ring' on the facts of the case. However, the Commission respectfully makes the following (critical) observations on the approach adopted in the judgment at first instance. 22 64. Firstly, the learned judge did not explain the evidential basis which had persuaded him that the Minister had given 'due regard' to the need to avoid unlawful discrimination, as was required by s149(1)(a) EqA. The materials before the Court do not suggest that the Minister was aware of how, if at all, the adoption of the measures might discriminate against disabled people in relation to independent living. 65. Secondly, since it cannot rationally be said that the decision would not have any adverse impact on equal access to independent living for disabled people, the learned judge did not explain how the Minister had addressed (given 'due regard') to the issue of whether they were justified. Had she done so, having regard to the obligations undertaken by the UK under the UNCRPD she would have had to address why taking another course would have imposed (in Lord Carnwarth's words in the AM case) a 'truly disproportionate' burden on the State. 66. Thirdly, the judge did not address the issue of the Minister's compliance with her duty under s149(1)(b) EqA 2010 to give 'due regard' to the need to advance equality of opportunity through the prism of s149(3). He did not consider whether the Minister had addressed her mind - as s149(3) required - to the specific disadvantages facing disabled people who wished to live independently; or what could be done to minimise those disadvantages. He therefore did not explain how she had satisfied him that she had given 'due regard' to the likely impact of her decision on opportunity for disabled people to live independently, given the complete lack of evidence that she had addressed or understood any of the matters which s149(3) EqA states are 'involved' in giving such due regard. 67. Fourthly, he failed to explain how the Minister could have appreciated the scale, nature and extent of the potential impact of the proposals on the opportunity for disabled people to live independently, without fairly consulting on the (effective) removal of any ring-fenced funding for independent living for disabled people, and the (highly likely, and severe) diminution in funds available for independent living given the abolition of the 'devolved' funding in 2015. This point is a fortiori given the absence of any other 23 form of evidence gathering on the implications, as suggested by the EHRC's Technical Guidance and as required as a matter of international law by Article 31 UNCRPD. 68. Fifthly, the learned judge erred at [53] AB/1/53, in holding that ministerial statements expressing concern for independent living, and the title of the relevant division of the government department in question themselves suggested that 'due regard' was given to the need to advance equality of opportunity in relation to independent living and/or the UK's commitments under Article 19 UNCRPD. He did not explain how 'namechecking' of personalisation and independence could amount to compliance with s149(1)(b) EqA read so as to give any meaningful effect to s149(3). That did not evidence any attempt 'in substance' or 'with rigour' to address (give "due regard") the barriers to independent living for disabled people or to consider ("give due regard") the measures which could be taken to minimise them, before deciding whether or not some such existing measures should be removed. Cf Chavda at [40]: "... It is important that [decision-makers] should be aware of the special duties [the decision-making body] owes to the disabled before they take decisions. It is not enough to accept that the [decision-making body] has a good disability record and assume that somehow the message would have got across ...". 69. Sixthly, the learned judge did not bear in mind that the Defendant's failure in consultation and adequate evidence gathering was contrary to the EHRC's Technical Guidance, and did not require therefore, any explanation for departure from those standards (cf Aikens LJ in Brown at [119]-[120], see para [12] above). 70. Seven, the learned judge was wrong (at [54]) AB/1/53) to seek to confine the (binding) effect of the decision of the Court of Appeal in Burnip as to the implications of the UNCRPD at [19]-[22] to its own particular 'context'. Burnip was a successful challenge to the general compatibility of a set of Regulations with Article 14 ECHR having regard to their impact on disabled people. Although the point of law arose in appeals from the Upper Tribunal and not by way of judicial review, the case was not about 'individual decisions on care packages', but about a statutory barrier to a claim for housing benefit for accommodation required in relation to disability-related need. In any event, 24 Maurice Kay LJ's observations on the implications of the UNCRPD as a specialist instrument for the interpretation of concepts of discrimination and justification were not context-specific and were based on Grand Chamber judgments of the ECtHR. 71. Finally, the learned judge erred (at [55] AB/1/53-54) in drawing comfort from the fact that the public sector equality duty imposes a continuing obligation. He held that any implications of the decision for independent living could be revisited if the (assumed) legislative reform were stalled or diluted, or if Treasury funding for disabled people generally or ILF users in transition in particular was 'so austere' as to leave 'no option' but to reverse progress already achieved in independent living. 72. This approach failed to give effect to the first Brown principle: that due regard must be given to equality at a formative stage. The learned judge failed to recognise that by the time the consequences of the decision are felt, it would be too late: the ILF would have closed. Moreover, since any ring-fenced funding would already have gone, if any one of the 20,000 people likely to be affected lost his or her ability to live independently, it would be hard to identify the source of the problem. It is well known that local authorities face and will continue to face acute financial shortages, and the removal of any ring-fenced funding for independent living would almost inevitably mean a reverse in progress and retreat from equality of opportunity. It was therefore at that point that due regard was needed to avoid the creation of inadvertent disadvantage. The purpose of the statutory duty is to give 'due regard' to the equality implications in advance, so as to avoid adverse implications being noticed or properly appreciated only when it is already too late to reverse them. HELEN MOUNTFIELD QC Matrix Chambers 22 August 2013 25 ANNEX - THE UN CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 2006 1. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its Optional Protocol were adopted by the UN General Assembly on 13 December 2006. The CRPD came into force on 3 May 2008. It has 103 states parties. The UK ratified the CRPD on 8 June 2009 and the Optional Protocol on 7 August 2009, and the EU ratified it in relation to powers within its competence on 23 December 2010. 2. The purpose of the UNCRPD is described in article 1 as being “to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity” (emphasis added). In other words, CRPD imposes positive obligations on states parties to address and remove the obstacles faced by disabled people in realising their rights. 3. The following provisions of the UNCRPD are particularly material (italicised emphases added): Article 1 – Article 1 includes in the definitions of persons with disabilities “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation on an equal basis with others". Article 2 – definitions defines “discrimination on the basis of disability” as meaning “any distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field. It includes all forms of discrimination including denial of reasonable accommodation” (ie reasonable adjustments to usual practises to accommodate particular needs). Article 3 sets out the principles of the Convention. These include non-discrimination; full and effective participation and inclusion in society; respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity and equality of opportunity. Article 4 requires states parties to “ensure and promote the full realisation for all person with disabilities without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability”, and to take a number of specific steps to this end. 26 The obligations under Article 4 include an obligation to “adopt all appropriate legislative, administrative and other measures for the implementation of the rights recognised in the ... Convention”; to “take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs or practices that constitute discrimination against persons with disabilities”; and – critically in this context - to "take into account the protection and promotion of the human rights of persons with disabilities in all policies and programmes”; and “refrain from engaging in any act or practice that is inconsistent” with the Convention and “to ensure that public authorities and institutions act in conformity with the ... Convention” (Articles 4 a, b, c, d). Article 5(3) provides that “in order to promote equality and eliminate discrimination, States Parties shall take all appropriate steps to ensure that reasonable accommodation is provided”. Article 5(4) provides that specific measures necessary to achieve de facto equality shall not be considered discrimination. Article 19 provides that “States Parties to this Convention recognise the equal right of all persons with disabilities to live in the community, with choices equal to others, and shall take effective and appropriate measures to facilitate full enjoyment by persons with disabilities of this right and their full inclusion and participation in the community, including by ensuring that a. Persons with disabilities have the opportunity to choose their place of residence and where and with whom they live on an equal basis with others and are not obliged to live in a particular living arrangement; b. Persons with disabilities have access to a range of in-home, residential and other community support services, including personal assistance necessary to support living and inclusion in the community, and to prevent isolation or segregation from the community; c. Community services and facilities are available on an equal basis to persons with disabilities and are responsive to their needs. (emphasis added). Article 31 requires states parties to collect appropriate information, including statistical and research data, to enable them to formulate and implement policies to give effect to the UNCRDP. 27 C1/2013/1283 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL (CIVIL DIVISION) ON APPEAL FROM THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE ADMINISTRATIVE COURT BETWEEN:THE CROWN ON THE APPLICATION OF BRACKING & OTHERS Appellants - and – SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK & PENSIONS Respondent -andTHE EQUALITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Intervener ___________________________________________ INTERVENTION SUBMISSIONS OF EQUALITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION ___________________________________________ Clare Collier Senior Lawyer, Equality and Human Rights Commission 3 More London Tooley Street London SE1 2RG 28