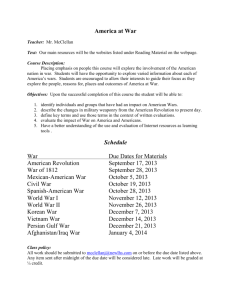

Is War Rational? - University of Notre Dame

advertisement