Online discourse in a teen chat room: New codes and new modes of

Study Title: Online discourse in a teen chat room: New codes and new modes of coherence in a visual medium

Study Author: Greenfield P. & Subrahmanyam, K.

Publication Details: Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 24, pp.713-738.

Summary:

What did the research aim to do?

The study aimed to examine online chat communication as a new communicative register, understood in terms of the social and communicative conventions of language use. The authors examined how conversational coherence is established and maintained when many traditional, face-to-face communicative conventions no longer hold within social interactions (e.g., when conversations no longer comprise adjacent pairs in interactional ‘turns’; and when multiple conversations are taking place concurrently within the one setting or transcript).

How was the study designed?

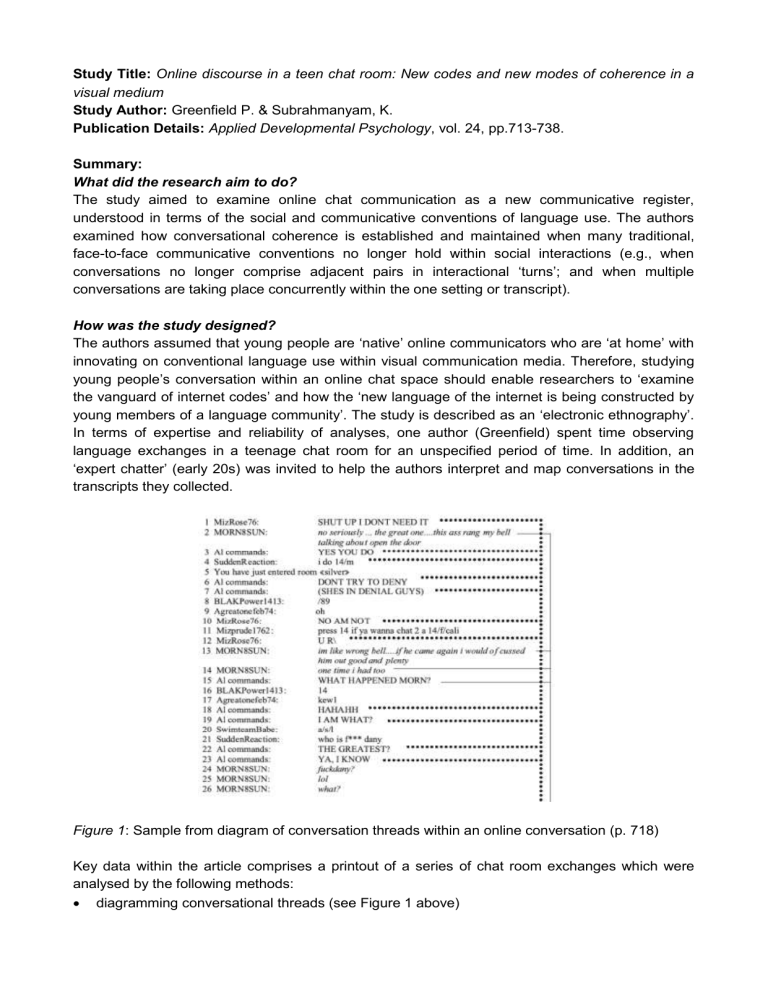

The authors assumed that young people are ‘native’ online communicators who are ‘at home’ with innovating on conventional language use within visual communication media. Therefore, studying young people’s conversation within an online chat space should enable researchers to ‘examine the vanguard of internet codes’ and how the ‘new language of the internet is being constructed by young members of a language community’. The study is described as an ‘electronic ethnography’.

In terms of expertise and reliability of analyses, one author (Greenfield) spent time observing language exchanges in a teenage chat room for an unspecified period of time. In addition, an

‘expert chatter’ (early 20s) was invited to help the authors interpret and map conversations in the transcripts they collected.

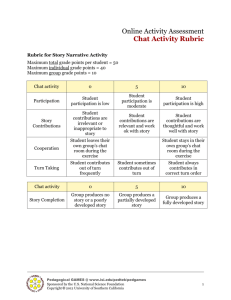

Figure 1 : Sample from diagram of conversation threads within an online conversation (p. 718)

Key data within the article comprises a printout of a series of chat room exchanges which were analysed by the following methods:

diagramming conversational threads (see Figure 1 above)

constructing taxonomies of cues and strategies (see Table 1 below)

focusing analysis on two communicative functions: identification of self and of conversation partners (i.e. ‘role’ functions); and establishing connectivity between utterances by producing or recognising a relevant utterance or response within a context of multiply-threaded conversations (i.e. ‘relevance’ functions).

What were the findings?

The authors found that the visual nature of online chat media enables participants to modify existing spoken and written communication strategies and to create new strategies to meet their communication needs (see Table 1 below). The authors also found that participants may participate in more than one conversation at a time. Moreover, in terms of conversational coherence, speed of communication matters online and online conversations often include:

short utterances

incomplete, grammatically simple or incorrect utterances

typographical errors or deliberate lack of capitalisation

omitted punctuation and

lexical truncation and abbreviations (e.g., ‘lol’ for ‘laughing out loud’).

According to the authors, the role functions and the relevance functions developed and deployed within the online conversation by participants established conversational coherence by the following means:

applying conventional face-to-face oral conversation strategies (e.g., the use of a name to affirm conversation partners)

adapting conventional strategies from spoken language interactions to the written medium (e.g. repetition of part or all previous relevant utterance to signal what is being responded to)

generating entirely new strategies for maintaining conversational coherence, such as visual cues (e.g. the idiosyncratic use of colour and font style by a particular participant, using nicknames or aliases that signal identity elements, emoticons); and chat code conventions (e.g. using numbers to find chat partners, such as ‘press 14 if ya wanna chat 2 a 14/f/cali’, that is, a

14-yearold female in California’; or ‘slot filler codes’ such as ‘a/s/l’ which invites participants to divulge their age, sex and general location).

What were the limitations?

The study reports on only a small fragment of online chat data from within one chat space devoted to teenagers and as such is not necessarily generalisable. The authors claim the study is an electronic ethnography, but focus only on language use as presented in one printout of chat conversations. The authors themselves admit they were not able to contact chat room participants due to university ethical clearance rules and thus were not able to obtain ‘insider’ interpretations of the conversations that they ob served. This makes their study more an ‘observation’ study than an ethnography per se. Thus, while one author is described as a ‘participant observer’ in the chat room, she functioned more as a passive observer, if not a ‘lurker.’ She interacted only when someone private messaged her, replied briefly, and not within the public conversation space.

What conclusions were drawn from the research?

The authors argued that online chat is a written register that makes use of many of the stylistic features of spoken language. In addition, the visual nature of online chat assists with conversational coherence by means of nicknames, font types, text colours, and chat language conventions like abbreviations. With respect to the main implication of their study, the authors proposed that conversational coherence in online chat is obtained by adapting available communication strategies and generating new ones in ways that enable participants to recognise and select conversational partners (role functions) and to recognise and participate in coherent conversations (relevance functions).

What are the implications of the study?

The authors predicted that online interactions will increasingly push written registers towards spoken registers. If this proves correct, teachers may need to rethink the strong emphasis in classrooms —especially in upper level classes—on written registers. Moreover, reading and writing instruction may need to engage with the complexities of new forms of cohesion practised in online conversation texts. With respect to research, chat provides investigators with an opportunity to document rapid language evolution due to the hybrid conversation medium provided by online chat spaces. Adolescents —the ‘first native speakers of the chat register’—will play critical roles in this language evolution process and their online conversation practices are therefore worth studying in more depth. This article may prove useful for ‘outsiders’ in terms of helping them navigate the complexity of online chat spaces which may appear bewildering and alien to some.

Where can interested readers find out more?

Subrahmanyam, K., Kraut, R., Greenfield, P. & Gross, E. 2001, ‘New forms of electronic media:

The impact of interactive games and the Internet on cognition, socialization a nd behavior’ in

Handbook of Children and the Media , eds. D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer, Sage, Thousand Oaks,

USA.

Keywords: literacies, multiliteracies, adolescents, youth culture, new technologies