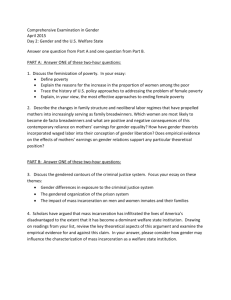

Ann Shola Orloff

advertisement