Ramses II`s Abu Simbel - Western Oregon University

advertisement

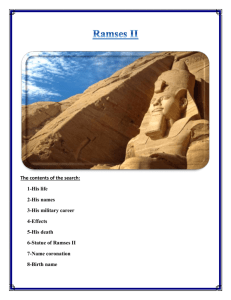

Kathleen Willey History 538 11/16/2009 The Function of Reliefs and Statues at Abu Simbel “The Egyptian pharaoh was considered the embodiment of Horus on earth and son of the sun god Re. Serving in this sacred role, the king provides a bridge between the earthly sphere and the world of the gods.” (Hawass, 2000) Believing that there was a sacred trust passed from the gods to the ruling pharaohs, ancient Egyptians believed the pharaoh’s nature to be divine. During the New Kingdom, the priests of the god Amun grew in power and therefore were seen as a threat to the power of the King. To counter this, Eighteenth century pharaohs focused praise on other gods, such as Re and Ptah, as well as placing “special emphasis on the worship of the living pharaoh.” (Hawass, 2000) To spread and encourage this change in devotional focus, rulers would; build temples dedicated to the worship of the living king, link the pharaohs with different gods within these temples, and inscribe statutes in and around the temples with the names expressing the divinity of the pharaoh. (Hawass, 2000) Although these efforts allowed for the divine connection of the pharaoh and the gods to be instilled widely, in order to become a god, the king must achieve several goals set by the gods themselves; build themselves a tomb, build temples for the gods, defeat Egypt’s enemies, present the gods with offerings and promise to unite upper and lower Egypt. (Hawass, 2000) An excellent example of a pharaoh’s attempt to fulfill these goals is seen in the reliefs and statues at the temples of Ramses II and his wife Nerertari at Abu Simbel. The grandiose statues, detailed reliefs and the magnitude of these temples all manifest into the propaganda that allowed Ramses II to accomplish his sacred duties and achieve his highly powerful status. This paper will examine several prominent reliefs and statues of the temples and how they function as political and spiritual representations of Ramses II’s power, strength and divinity. Upon the return of King Ramses II from battle in Kadesh, the commission of the temples at Abu Simbel was ordered. Taking nearly twenty years to complete, the temples at Abu Simbel are considered to be some of the most remarkable achievements of the ancient world. (Hawass, 2000) The temple of Ramses II, or the Great Temple, is dedicated to four gods; the sun god and the god of the North, Ra-Horakhty (culmination of the gods Ra and Horus), Amun-Ra, the god of Thebes and the god of the South, Ptah, the god of Memphis, and the deified Ramses II, the king god. The reasoning behind dedicating the temple to more than one god had three purposes; first, to fulfill the promise of guaranteeing the unification of Egypt through the reconciliation of the main deities of Lower and Upper Egypt (Amun-Ra and Ra-Horakhty) secondly, to strengthen worship of other gods (such as Ptah) as set forth by the eighteenth dynasty, and third, to further promote Ramses II as a god, for it is his deified self that is included in the list of gods the Great Temple is dedicated to. The temples at Abu Simbel are much like the usual prototype plan of an Egyptian temple, except for the lack of an open courtyard, which is due to the temple being cut into a cliff side. (Choukry, 2008) The Great Temple also features a spectacular façade, which replaces the traditional pylon of a free standing temple due to the construction methods, however is still trapezoidal in shape. The shape of the façade itself mimics the shape of the anket [akhet] or horizon hieroglyph, (Wilkinson, 2000) symbolizing rebirth or recreation, as the horizon symbolizes the western desert, or image of what is beyond now, the afterlife and realm of the dead. The façade is preceded by a forecourt, decorated with statues of the king and of the god Horus. The forecourt also contained two tanks for the ablutions of the priests flanking the stairs leading to the entrance. (Wilkinson, 2000) With the tanks outside, ceremonies and special occasions were celebrated at the foot of the temple, allowing the view of the grand facade to seen by the masses, a strategic move on behalf of Ramses II which will be discussed later. Above the entrance to the Great Temple is a relief of the falcon headed god Ra-Horakhty and Ramses II, who depicted handing a statuette of the goddess of justice, Maat, to the god. This relief represents the cryptogrammic way of writing the King’s birth name, User-maat-ra meaning “Powerful is the justice of Ra”. The placement of the name above the entrance to the temple indicates the temple is dedicated to a divine form of Ramses II (Choukry, 2008 & Robins, 1997) and as previously described, inscribing the names which express the divinity of the pharaoh further promote the divine nature of the king. Fronting the façade are four colossi, or giant stone images of Ramses II. Ramses II was especially enamored of these colossal figures and had more, and larger, statues carved than any pharaoh before or after him. (Wilkinson, 2000) The statues on the south side of the entrance at Abu Simbel are of Ramses II himself, the two to the north of the entrance are of Ramses II, the god. (Choukry, 2008) The function of colossi is of great importance. As one would suspect, they did serve a protective role to the Great Temple itself. Their size reaching upwards of 22 meters in height would be intimidating to any approaching enemy. They were a sign of the great wealth and power that the Egyptian Empire held and served as a forewarning to any foe entering from the south. Their main purpose however was to show the inseparable relationship of the king with the gods at a level close to that of the divine. (Wilkinson, 2000) “As manifestations of the pharaohs they represented, they [colossi] were usually accessible to the people or in areas which were at least open on special occasions…and worshipped directly by the people, acting as intercessors with the gods…in their own right.” (Wilkinson, 2000) Access to the inside of the temple was limited to that of pharaohs and priests, but by placing the divine colossi outside and the name relief above the entrance, they were accessible to the common populace. Through this placement, Ramses II affirmed his divine nature to the people, thereby preventing revolt against the god king. Reaffirming his divinity to the people would also prevent uprising of the priests of Amun, by creating a resistance of those who would not let a god be usurped. (Choukry, 2008) The placement of the Great Temple in Nubia itself was also a strategic move. Nubia was considered a gateway to the south, giving Egypt a source of raw materials, most importantly gold. Nubia also provided a source of manpower for building projects and military expeditions. Although Nubia was controlled by Egypt, it was not considered to be Egypt but thought of as a region of protection or first line of defense for the southern territory against enemy states. (Choukry, 2008) By building temples in threatened regions such as Nubia, kings prevented turmoil and rebellion by “Egyptianizing the people of Nubia and guaranteeing their loyalty to the pharaoh as the embodiment of god on earth.” (Hawass, 2001) Below the colossi are the images of eleven members of the king’s family including select children, wives and his mother. The depiction of his family members had the function and purpose to bring eternal life and as a paean to them. At the base of the colossi’s thrones, which flank the entrance, are the reliefs of the Sematawy, the symbolic union of Upper and Lower Egypt. This is depicted by a scene of the god of the Nile, Haapy or Hapi, tying the lotus flower (representative of Upper Egypt) and the papyrus plant (representative of Lower Egypt) around the hieroglyph for unite, which is said to be a representation of the Nile. (Hawass, 2001) This relief is propaganda in the sense that Ramses II is being said to be fulfilling his godly guarantee of preserving the unity of both Upper and Lower Egypt. Below the Sematawy reliefs, are another set at the ankles of the colossi. They are symbolic to Egypt’s borderland enemies; the Asiatics and Libyans which are found on the northern colossi and Africans which are on the southern colossi. These reliefs have the function of showing to the people and to the gods that the enemies of Egypt are “eternally bound under the feet of his majesty the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ramses II. “ (Choukry, 2008) This symbol reaffirms Ramses II as fulfilling his duty and king and god to not only smite the enemies of Egypt, but unify Upper and Lower Egypt under one rule. On the terrace to the Great Temple are several stelae, the most important of which depicts the marriage of Ramses II to the Hittite princess. Considered one of Ramses II’s most diplomatic triumphs, the marriage was designed to consolidate the ties of peace and friendship between Egypt and the Hittite Empire (Hawass, 2001) the result of an episode which will be discussed at length further on, Kadesh. The princess’ diplomatic importance is summed up in this inscription within the stelae, “from now on, if a man or woman travels to Syria for any reason, they can reach the land of the Hittites without any fear as a result of his Majesty’s victories.” (Hawass, 2001) Much like the colossi, this proclamation of victory was placed outside to prove to the people and the gods that Ramses II was fulfilling his duties as both king and a god. The first hall of the Great Temple is the pillared hall. The ceiling is held up by eight square columns, four on each side. These columns are engraved with reliefs of Ramses II and his wife Queen Nefertari presenting various offerings to several gods; Hathor, Maat, Amun-Ra, Ra Horakhty, Onuris-Shu, Thoth, Mut, Satis, Anubis, Isis and Amun-Min Kamutef. The first column on the south side shows Ramses II king burning incense before Ramses II god. (Choukry, 2008) Presenting offerings to the gods is one of the goals set forth by the gods to the pharaohs to become gods themselves. The function of these reliefs, especially the one of the first southern pillar, suggests that Ramses is not only proving his eternal piety to the gods, but considers himself one as well. The variety of gods being presented offerings on these columns support the reformation of religious practice made during the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties. The primary focus on Amun presented a power conflict with the god’s priests and the king, as previously discussed. By linking himself with a variety of gods as well as depicting himself as a god, Ramses II was placing special emphasis on himself as a godly and divine being. The eight columns are fronted by eight colossi of Ramses II depicted as the god Osiris, further supporting the chthonic theme of the temple complex. (Wilkinson, 2000) These statues depict Ramses II holding the emblems of kingship; the crook and the flail, but the rows of statues are wearing two different crowns. The statues on the south side represent the king wearing the double crown of Egypt, while the statues on the north side of the pillared hall represent the Osirid king wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt. (Choukry, 2008) These grand statues hold two functions; the first is to unite all of Egypt through the representation of two separate crowns on the king’s head, and second is to make the connection of Ramses II as both king and god by holding the kingly emblems, but being depicted as the god Osiris. Also within the pillared hall of the Great Temple are reliefs on each surrounding wall. They were formed in different historical epochs under the influences of different factors, but their common object was to glorify the ruler, to show his superhuman power and the divine character of the king's authority, and to support his imperialistic policy of conquest. (Sliwa, 1974) Many of the reliefs here at Abu Simbel are not unique to this temple complex, as will be discussed upon the analysis of each relief, but they do serve as visual representations, often biased and improvised, of the king's success , authority and divinity. The East wall of the pillared hall, the entrance wall, contains two scenes of Ramses II smiting his enemy. On wall north of the entrance, Ramses II with his Ka is smiting Libyan enemies before Ra-Horakhty. The wall south of the entrance is Ramses II smiting Nubian and Hittite enemies before Amun. The significance of these two reliefs is multifaceted. First of all, smiting scenes are not uncommon in Egyptian history, even being seen in first dynasty art. Within this propaganda, representations of the enemy [Libyans, Hittites and Nubians] themselves is highly discriminatory, emphasizing ethnic features and adding comic elements which greatly contrasts the realist dignity of the pharaoh's figure. (Sliwa, 1974) The purpose of a smiting scene is to portray the victor, in this case Ramses II, as taller, more powerful and of more importance than his enemy. (Sliwa, 1974) Secondly, both the smiting scenes on the east wall of the pillared hall are done so in the presence of a god, which indicates that the sacrifice of the enemy is done so in the honor of that god. Furthermore, the gods being honored, Amun and Ra-Horakhty, are on the walls corresponding to their region of influence. Amun, the god of the South, is being honored on the southern part of the eastern wall. Likewise, Ra-Horakhty, the god of the North, is being honored on the northern part of the eastern wall. The purpose behind this is not just to prove Ramses II's eternal piety to these gods or to show he his fulfilling his duty of eternally smiting the enemies of Egypt, but to reconcile the main deities of North and Upper Egypt. (Choukry, 2008) This theme is one that will continue throughout the reliefs of the Great Temple. Lastly, the scenes on the eastern wall are unspecific of any particular event and it is probably for this reason many scholars are unwilling to tie these reliefs with any preserved wars of Ramses II. (Spalinger, 1980) This information along with the characterization of the king and enemies themselves, these reliefs hold the ultimate function of being purely political and promotional in nature and not of historical accuracy. The southern wall of the pillared hall is divided into two sections. The first is a series of offering reliefs of Ramses II presenting the gods; Merymutef, Ra-Horakhty, Ipet, Amun and Ptah with incense, cloth, libations and other offerings. Offering scenes, much like smiting scenes, are seen in many other Egyptian reliefs and pieces of art. The purpose of this scene is to depict the eternal piety and dedication to the gods as well as to show Ramses II fulfilling the goals of godliness himself. The second section, which is below the first, depict three separate battle scenes; the first against the Syrian fortress of Tunip and Dapur, the second against the Libyans and the third against the Africans. Like the smiting scenes of the east wall, the lower portion of the southern wall functions as the proof of Ramses II destroying the enemies of Egypt, preserving its culture, power and way of life. The western wall of the great pillared hall is divided into two sections, much like that of the eastern wall. Separated by the doorway leading to the second pillared hall, the northern and southern scenes depict Ramses II leading prisoners of war toward various gods. The northern wall shows Ramses II driving defeated Hittites to Ra-Horakhty, the lioness goddess Lusas as well as the deified Ramses II. The southern wall shows Ramses II driving Nubian prisoners to Amun, Mut and like the northern section, the deified Ramses II. These scenes, much like the ones on the eastern wall, place Amun, the god of the south, on the southern wall and RaHorakhty, god of the north, on the northern wall. Unlike the scenes on the east wall, however, the inscriptions accompanying the ritual act are more precise, specifically mentioning Hatti (Hittites) on the northern wall and Kush (Nubians) on the southern. (Spalinger, 1980) The New Kingdom focused a great deal on the capture of foreign people which played a fundamental political and propagandistic role. (Sliwa, 1974) As with the other reliefs of Abu Simbel, the purpose and function of both the northern and southern reliefs is to glorify Ramses II, show his power and his authority. However, the western wall also depicts Ramses II as god, which the other walls omit. This additional function of the western wall is to further connect Ramses II not just with a divine nature, but to show that Ramses II himself was a god to the level equal to Amun and Ra-Horakhty, national gods. Finally, the northern wall is a detailed depiction of the battle at Kadesh. Covering the entire wall, this panoramic relief records the "significant details of a conflict in which his [Ramses II] courage saves his army from disaster". (Kantor, 1957) The historical account of Ramses II fighting in Kadesh is seen in many of the king's temples, for it is was his greatest military accomplishment. (Wilkinson, 2000) Temples in Abydos, Luxor and the mortuary temple in Thebes, the Ramesseum, all have reliefs depicting Kadesh. In a fight against the Hittites, Ramses II encountered bad intelligence regarding the location of the enemy forces. Surprised and outnumbered by the Hittites, the Egyptian forces were helped by the last minute arrival of an additional division, forcing the Hittites to declare a stalemate. Ultimately, nobody won as Kadesh remained untouched even if, sometimes, the pictorial reliefs and texts did not show this reality as it was. (Choukry, 2008) The reliefs on the north wall suggest victory in two manners; Ramses II riding a chariot, and by conducting prisoners, like that seen on the western wall. Battle scenes, in which the pharaoh takes direct part from his battle chariot and shooting a bow or fighting with another weapon, rides over a crowd of the enemy, are typical of the New Kingdom. (Sliwa, 1974) This aspect of the relief combined with the reliefs of the king's chariot directing prisoners, testified both to Egyptian power and to the military successes of individual leaders as well as intensified the dignity of the victorious ruler. (Sliwa, 1974) Many theories exist to explain the function and purpose of the relief of the battle at Kadesh. The first suggests that the relief is a depiction of a physical battle that took place and is just a snapshot into the victory of a king. The second theory, as seen in the following quote, is that Kadesh was an abstract campaign, one in which the king is hopeful and expectant of the events within the relief to play out in future events. "True, Kadesh was not taken, and the Hittite had truculently annexed Upi as well as Amurru once more, but (in Ramses' optimistic view) this could all be put right in a year or two, with better military intelligence and a fully refurbished army. In that light, his heroics as Kadesh would not be the end of a dream, but the herald of greater achievements to come." (Kitchen, 1982) Lastly, as supported through the following quote, the relief is a generalized eternal conflict. "Although it is not clear that the battle of Kadesh was not an outright victory, the scenes that Ramses ordered carved on the walls of his temples show him victorious over his enemy. The reason is that these drawings represent not just this specific battle between the Egyptians and Hittites, but the eternal battle for order over chaos. The Egyptian king, as the earthly manifestation of the creator god, must always be shown as victorious, thus ensuring the proper functioning of the Egyptian universe." (Hawass, 2001) Judging by the propagandist nature of the other reliefs within and outside the temple at Abu Simbel, the third theory is most likely true. Leaving the great pillared hall, the floors of the rooms noticeably rise, following the basic convention of temple design in a somewhat foreshortened manner. (Wilkinson, 2000) Symbolic of the rise to the primordial mound, this incline continues to the back of the temple to the sanctuary. Leading to the sanctuary are the second pillared hall and the vestibule. The second pillared hall contains four pillars, two on each side, and are decorated much like the pillars in the first pillared hall as well as have the same function, to show eternal piety. The eastern wall of the second pillared hall has images of the deified Ramses II making offerings to Amun and Mut, The most important relief in this room are the ones on the north and south side, which are similar in theme. In these reliefs, Ramses II followed by Nefertari are advancing on the barque of god Ramses II on the north wall and the barque of the god Amen on the southern wall. It is in these reliefs, though, that the Queen Nefertari is shown as of equal height to Ramses II (Choukry, 2008), which is, as will be discussed later, of significant importance to the power and deification of the Queen. The second pillared hall leads into the vestibule, which is decorated with more reliefs showing Ramses II with offerings to many main and local deities. (Choukry, 2008) The most sacred and important part of the entire temple structure is the sanctuary itself, which is just beyond the vestibule. Much like the colossi featured at the facade of the Great Temple, there are four large sitting statues of the gods (right to left) Ptah, Amun, Ramses II as god and Ra-Horakhty. The choice and positioning of these gods was strategic and can be interpreted to show the political and religious balance of power among the cities of Heliopolis (the city of Re-Horakhty), Thebes (the city of Amun), and Per-Ramesses (the city of Ramses himself). (Hawass, 2001) The presence of these statutes in this particular order also follows the division of the temple into two symmetrical parts, Amun sitting on the south end of Ramses II and Ra-Horakhty sitting on the north end, as comparable with the north and south reliefs in the great pillared hall. (Choukry, 2008) These statutes are also a clear indication of the king's political and religious compromise to satisfy the priests of the main deities of the time, (Choukry, 2008) further diminishing the power of Amun's priests and instilling the connection between Ramses II to the divine, therefore increasing his ultimate power. By placing himself as a god in the sanctuary, Ramses II king was adding yet another aspect to his temple that showed he viewed himself as a god comparable to the divine level of the national gods of Egypt, therefore, of utmost importance. A little over 100 meters to the north of the Great Temple is the temple of Queen Nefertari, or the Small Temple, dedicated to the goddess Hathor. Cut into the rock of the cliff side, the Small Temple has many of the same features discussed at the Great Temple as well as reliefs and statues that not only further deify her husband Ramses II, but herself as well. The facade is much like that at the Great Temple, a trapezoidal shape representative of the horizon and therefore the afterlife. The six colossi fronting the facade are not as large as the four seen at the Great Temple, only reaching a height of 11 meters, but do hold a similar purpose. Three colossi are standing on each side of the Small Temple's entrance, two of King Ramses II surrounded by Queen Nefertari. Three of the four statues of Ramses II wear the double crown, while the fourth one has the Nemes head cloth surmounted by ram's horns, the solar disc and two ostrich feathers, and protected by two cobras. The statues of Nefertari show the queen wearing the emblems of the goddess Hathor, the two cow's horns and the solar disc. (Choukry, 2008) The decor of these colossi suggest the divine nature of not just Ramses II, but of Nefertari as well. Her connection to the goddess Hathor, the deity most closely associated with queenship in ancient Egypt, is an affirmation of her religious role in the temple as a goddesses' high priestess. (Choukry, 2008) The uniform height of these colossi also serve an important function, the fact that the statues of Ramses II are the same height as those of his queen show that, as seen in the Great Temples second pillared hall, Nefertari is of equal importance of connection to the divine. The first room of the temple, the hypostyle hall, is columned much like that of the Great Temple. The columns feature many scenes of Ramses II and his wife making offerings in front of several local deities, further promoting both their piety and divine natures. (Choukry, 2008) Within the temple's vestibule, one particular scene shows Nefertari being crowned by goddesses Isis and Hathor. Transforming the queen into Sothis, a living goddess, Nefertari's divinity within this scene is assured by the beautiful sign of life that she is holding in her hand, an ankh. (Choukry, 2008) Normally such divine coronation scenes are reserved for the king, showing unusual prominence for the queen. (Robins, 1997) Ramses II, however, continues to reaffirm his deified self throughout the Small Temple as in the Great Temple. Scenes within the Small Temple's sanctuary depict Ramses II making offerings to both the deified Nefertari and Ramses II. These divine reliefs within the Small Temple hold one function, to promote the godly connection and deification of both Ramses II and his Queen, proving to priests, people and gods that they are gods themselves. As shown through the examination of reliefs and statues at both the Great and Small temple at Abu Simbel, the underlying focus and purpose for these magnificent temples can be stated as an egotistical manifestation of propaganda that supports and enforces the perceived divine connection that king Ramses II and Queen Nefertari thought they had to the gods. Ramses II uses symbolism through scenes of war, offerings to the gods, representations of himself and his queen as a god and defeating all of Egypt's enemies to validate his divine lineage. The temples go on further to not only support a divine connection, but to declare this royal couple gods themselves, equal to that of Amun, Ra-Horakhty and Hathor. Placed in public, Ramses II utilized the reliefs and sheer magnificence of the temple itself to instill his divinity and the fear of the power of Egypt upon all who saw it. One of the most remarkable achievements of the ancient world, the temples at Abu Simbel combine magnificent art and piety into one of the most impressive examples of self-preservation in history. Bibliography Choukry, N., Abu Simbel (American University in Cairo Press, 2008). Hawass, Z., The Mysteries of Abu Simbel: Ramesses II and the Temples of the Rising Run (American University in Cairo Press, 2001). Kantor, H.J., ‘Narration in Egyptian Art’ in American Journal of Archaeology 61 (1957) 44-54. Kitchen, K., Pharaoh Triumphant: the Life and Times of Ramesses II (Aris & Phillips, 1982). Robins, G., The Art of Ancient Egypt (British Museum Press, 1997). Śliwa, J., ‘Some Remarks concerning Victorious Rule Representations in Egyptian Art’ in Forschungen und Berichte 16 (1974) 97-117. Spallinger, A.J., ‘Historical Observations on the Military Reliefs of Abu Simbel and Other Remesside Temples in Nubia’ in Journal of Egyptian Archeology 66 (1980) 83-99. Wilkinson, R.H., The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt (Thames & Hudson, 2000).