Consciousness as the Foundation for Metaphysics

advertisement

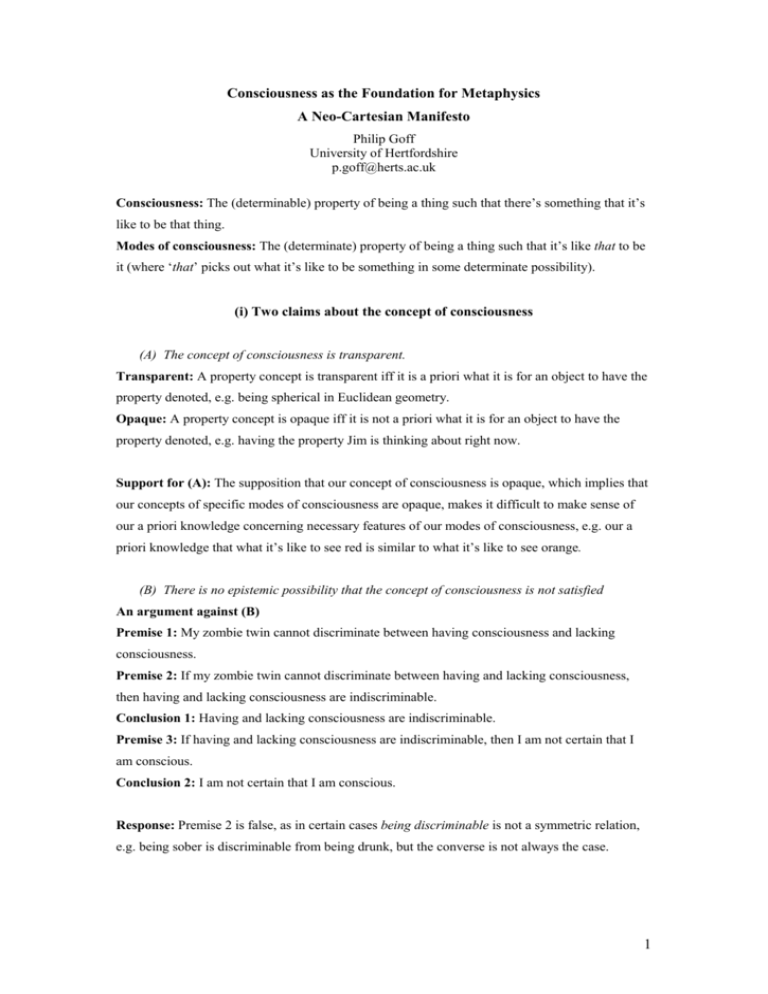

Consciousness as the Foundation for Metaphysics A Neo-Cartesian Manifesto Philip Goff University of Hertfordshire p.goff@herts.ac.uk Consciousness: The (determinable) property of being a thing such that there’s something that it’s like to be that thing. Modes of consciousness: The (determinate) property of being a thing such that it’s like that to be it (where ‘that’ picks out what it’s like to be something in some determinate possibility). (i) Two claims about the concept of consciousness (A) The concept of consciousness is transparent. Transparent: A property concept is transparent iff it is a priori what it is for an object to have the property denoted, e.g. being spherical in Euclidean geometry. Opaque: A property concept is opaque iff it is not a priori what it is for an object to have the property denoted, e.g. having the property Jim is thinking about right now. Support for (A): The supposition that our concept of consciousness is opaque, which implies that our concepts of specific modes of consciousness are opaque, makes it difficult to make sense of our a priori knowledge concerning necessary features of our modes of consciousness, e.g. our a priori knowledge that what it’s like to see red is similar to what it’s like to see orange. (B) There is no epistemic possibility that the concept of consciousness is not satisfied An argument against (B) Premise 1: My zombie twin cannot discriminate between having consciousness and lacking consciousness. Premise 2: If my zombie twin cannot discriminate between having and lacking consciousness, then having and lacking consciousness are indiscriminable. Conclusion 1: Having and lacking consciousness are indiscriminable. Premise 3: If having and lacking consciousness are indiscriminable, then I am not certain that I am conscious. Conclusion 2: I am not certain that I am conscious. Response: Premise 2 is false, as in certain cases being discriminable is not a symmetric relation, e.g. being sober is discriminable from being drunk, but the converse is not always the case. 1 (ii) How do we find out about the nature of reality? Suggestion 1: Science Problem: There are certain hypotheses about the nature of reality which empirical data cannot settle. Intra-object metaphysics: What is the nature of an object in general? (i) Realism about universals/tropes versus set nominalism. (ii) Realism about universals versus trope theory. (iii) Bundle theory versus substance-attribute theory. Object metaphysics: What objects are there? (i) Realism versus nihilism about inanimate composite objects. (ii) Perdurance versus endurance. Suggestion 2: Theoretical virtues Problem: Appeal to theoretical virtues, in and of itself, does not get us very far. Suggestion 3: Theoretical virtues in conjunction with a priori intuition. Problem: Intuition is a good guide to the nature of our concepts, but does not tell us which concepts are satisfied. Suggestion 4: Theoretical virtues in conjunction with a priori intuitions about consciousness (and science where relevant). The Neo-Cartesian Manifesto The metaphysician is to choose between metaphysical theories on the basis of, and only on the basis of: 1. Scientific findings or principles of theory choice which are involved in scientific enquiry. 2. A priori intuitions concerning the nature of consciousness. 3. The necessity for coherence. 2 (iii) The method in action Acceptable appeal to intuitions Against bundle theory? [It is] ‘ an obvious conceptual truth that an experience is necessarily an experiencing by a subject of experience, and involves that subject as intimately as a branch-bending involves a branch’ (Shoemaker 1990/1996: 10). Against austere nominalism ‘It’s hard to deny that there are natures or ways of being. They are most evident in our own conscious experiences, but the ‘what it’s like’ of consciousness is really just a special case of a way of being: it is a way an experience is’ (Robb: 2005: 466). Appeals to intuition which can be made acceptable Armstrong arguing against set nominalism ‘Is a thing the sort of thing that it is – an electron, say – because it is a member of the class of electrons? Or is it rather a member of the class because it is an electron?....it seems natural to say that a thing is a member of the class of electrons because of what it already is: an electron. It is unnatural to say that it is an electron because it is a member of the class of electrons. And that it is natural to put the property first and the class second is some reason to think that that is the true direction of explanation. This is bad news for any Class Nominalism…’ (Armstrong 1989: 27-8). Making it fit the party line: ‘Is a conscious thing conscious because it is a member of the set of conscious things? Or is it rather a member of the class because it is conscious?....it seems natural to say that a thing is a member of the class of conscious things because of what it already is: a conscious thing. It is unnatural to say that it is a conscious thing because it is a member of the class of conscious things…’ Martin arguing against bundle theory An object is not just a group of properties, because properties are not themselves objects to be grouped. An object, therefore, stands in need, not only of a set of properties as an ingredient, but also the ingredient of a bearer of whatever properties are borne….A particular shape or size has to be of something….what is referred to as the 'square shape' cannot be thought of under some other description as an object that could have existed without need of being the square shape of anything but as an object existing in its own right’ (Martin 1980: 7) Making it fit the party line: ‘A particular mode of consciousness has to be of something…what is referred to as the ‘feeling of pain’ cannot be thought of under some other description as an object that could have existed without need of being the painful feeling of anything but as an object existing in its own right.’ 3 Lewis arguing against relationalism, i.e. the view that all properties are relations to times ‘[Lewis starts by describing the view he is rejecting]….contrary to what we might think, shapes are not genuine intrinsic properties. They are disguised relations, which an enduring thing may bear to times. One and the same enduing thing may bear the bent-shape relation to some times, and the straight-shape relation to others. In itself, considered apart from its relations to other things, it has no shape at all….This is simply incredible….If we know what shape is, we know it is a property not a relation.’ (Lewis 1986: 204) Making it fit the party line: ‘….contrary to what we might think, modes of consciousness are not genuine intrinsic properties. They are disguised relations, which an enduring thing may bear to times. One and the same enduring thing may bear the feeling-pain relation to some times, and the feelings-pleasure relation to others. In itself, considered apart from its relations to other things, it has no mode of consciousness at all….This is simply incredible….If we know what a mode of consciousness is, we know it is a property not a relation.’ Unacceptable appeals to intuition An argument against four-dimensionalism ‘[for the four-dimensionalist] the variation of a poker’s temperature with time would simply mean that there were different temperatures at different positions along the poker’s time axis. But this, as McTaggart remarked, would no more be a change in temperature than a variation in temperature along the poker’s length would be. Similarly for other sorts of change’ (Geach 1972: 304) An argument against presentism ‘No man, unless it be at the moment of his execution, believes he has no future; still less does anyone believe that he has no past’ (Lewis 1986: 204) A neo-Cartesian argument for perdurantism Premise 1: The only coherent theories of persistence are perduantism, endurantism + presentism, and endurantism + relationalism. Premise 2: The reconstructed Lewis intuition shows relationalism to be false. Premise 3: Presentism is false, as shown by its inconsistency with relativity theory. Conclusion: Perdurantism is the true theory of persistence through time. Armstrong, D. M. 1989. Universals: An Opinionated Introduction, Boulder Colorado: Westview Press. Geach, P. T. 1972. ‘Some problems about time’, in Logic Matters, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Lewis, D. 1986 On the Plurality of Worlds, Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Martin, C. B. 1980 ‘Substance Substantiated’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 58: 1. Shoemaker, S. 1990/1996. ‘First Person Access’, in The First Person Perspective and Other Essays, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Robb, D. 2005. ‘Qualitative Unity and the Bundle Theory’, The Monist, 88:44. 4