Dualism (Plato, Descartes)

advertisement

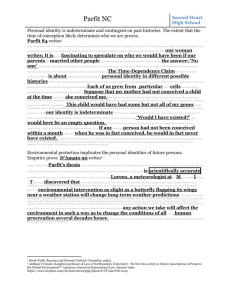

AGAINST PERSONAL IDENTITY Parfit: the question: “will I be the same person tomorrow” has no meaningful answer. The argument summarized: 1. Either dualism (“Ego Theory”) or else psychological continuity (“Bundle Theory”) are the correct theories of identity. 2. Dualism is false. 3. The Bundle Theory is incompatible with survival. 4. Therefore, personal survival is a myth. 1 Against dualism: Split brain cases Hemispheres of S’s brain have been severed: S observes a two-coloured screen. Left eye sees red; right eye blue. S is asked: (1) how many colours do you see? (2) What colour do you see? Right hand writes: (1) “One”. (2) Red. Left hand writes: (1) “One”. (2) Blue. Parfit: This shows that there are two streams of consciousness in one body. If dualism were true, the soul would unite the streams into one consciousness. Dualism must be false. 2 Objection There is only one stream of consciousness: the subdominant hemisphere is not conscious but is subordinated to the dominant one. Parfit: People have had their dominant hemispheres destroyed. They are changed but can still talk, move, respond and generally interact. So, subdominant hemisphere is conscious. So, there can be disunified streams of consciousness. This contradicts the idea of a unified soul. Bundle theory is the only way to go. 3 Implications of the bundle theory Teleportation: You are scanned at T1 in S1. You are destroyed. A replica is created at T2 in S1. Bundle theory: You survive because psychological continuity is preserved (in the right, causal way). Parfit: What if two copies are made? They can’t both be identical to you (2 ≠ 1). Conclusion: since each duplicate is psychologically continuous with you, psychological continuity is not sufficient for preserving identity 4 Against the No-Branching Clause Suppose that you are beamed somewhere. You open your eyes, look around, recall the teleportation and your childhood, and then get on with your mission. According to the Bundle Theory, you survive. If, however, 10 duplicates were to be teleported to the same room, none would be you. How can such an extrinsic fact be what determines whether you survive? 5 Summary On the Bundle Theory, there are only the following kinds of fact: Experiences exist. Some are psychologically continuous. But psychological continuity relates sets of experience that are not strictly identical. So this is possible: B C D E A Neither B, C, D nor E is identical to A. But if we remove B, D, and E, that can’t suddenly make C identical to A. 6 Operations Teleportation is like an operation where each of your cells is replaced by a duplicate. The above reasoning shows that 100% replacement destroys identity. But do you believe that, for example, 0.1% replacement does not destroy identity? If so, then you believe that: There is some critical percentage between 0.1% and 100% that marks the boundary between survival and death. Parfit: It is absurd to suppose there is a line at which removing one cell would destroy your identity, but not removing that cell would preserve it. 7 Impossible to find Parfit: What’s more, we could never detect where such a line would be. Say the crucial percentage is 49%. If 50% is replaced, you die. But the 50% replacement is psychologically continuous with you. So, we could never determine that s/he isn’t you. Conclusion: We should give up belief in such a line. 8 We are only bundles Parfit: If the bundle theory is true, then there is no point trying to find this line. There is no “you”, no Ego/substance that underlies your experiences. There are only the experiences. Here is a complete description: 1. John has 50% of his cells replaced. 2. Psychological continuity is preserved. 3. The continuity has an unusual cause. If we feel the need to ask: “But is the result really identical to John?” Then we have ignored the lessons of the bundle theory: There is no further fact of the matter besides 1-3 9 A short way of looking at it B1: 100% replacement destroys identity. B2: 0.1% replacement preserves identity. B1 + B2 = critical percentage = absurd. But B1 is proven by branching cases. So, must give up B2. 10 Lessons of the Bundle Theory Suppose Q (at T1) and P (at T2) are psychologically continuous experiences. Q: Are P and Q part of the same person? Parfit: What are you asking? 1. Same soul? No: dualism is false. 2. Strict identity (P = Q)? No: Leibniz’s Law. 3. Psych. Cont.? Yes. But: #3 may apply to many distinct bundles of experience: R (at T2), S (at T2), etc. may all be psychologically continuous with Q. Okay, but which one is really identical to Q? Parfit: senseless question: no more facts other than 1-3. 11 Surprising conclusion 1. You and your replica are psych. cont. but not identical. 2. Your experiences today and tomorrow are psych. cont. Therefore: 3. Future, psychologically continuous experiences are no more “you” than is your replica. In other words: There is no connection between “you” today “you” tomorrow that is not shared by you and possibly many distant replicas. Since there is no survival in the latter case, there is none in the former. 12 Final view: Dualism There are two questions to ask: 1. Conceptual: What is it for P2 at T2 to be identical to P1 at T1? 2. Evidential: On what grounds do we conclude P2 = P1? Swinburne: Most writers assume that the answer to #2 gives us the answer to #1. These are “empiricist theories” of personal identity. They are not satisfactory. 13 The story of empiricism 1. BODILY THEORY Problem: Body gains/loses parts. 2. PSYCHOLOGICAL CONTINUITY Problem: Teleportation/Duplication. 3. BRAIN THEORY Problem: Brains can be duplicated as well. 4. PARFIT: There is no (total) survival. Problem: How does Parfit know this? It could be that one part of the brain is the centre of experience (Chisholm). Parfit’s view needs empirical support that he doesn’t provide. 14 Response Swinburne: Bodily continuity Brain continuity Psychological continuity Are all (fallible) evidence of personal identity. However, what they are evidence of is distinct from these criteria. Personal identity the criteria we use to ascribe personal identity. Okay, but then what is personal identity? 15 The story of dualism Swinburne: Logic alone can’t tell us which set of future experiences I will have. That’s why the empiricist theories have so many counterexamples. Perhaps as a matter of fact I will have one and only one set of future experiences (even in teleportation cases). There may be empirical doubt as to which of a future duplicate is in fact me. But it doesn’t follow that there is no fact of the matter. 16 The mind-body relation For a body to be my body means: 1. I can move this body directly. I don’t need to do something else first in order to get my arm to move. 2. Empirical knowledge is gained through the body. What I know about the world is the result of the world’s effects on this body. In short: this body is my vehicle of agency in the world and knowledge of the world. 17 Minds are not bodies But then, it is entirely possible that I find myself: 1. Able to move another body directly. 2. Gaining information via another body. It is also coherent to suppose a person becomes disembodied: Able to move objects in a room directly (not through a body). Able to know where objects in a room are without seeing them. Disembodied survival is logically coherent: Minds are not necessarily bodies. 18 Against verificationism Swinburne: Body/brain continuity is our main evidence of personal identity. So: I can’t describe an actual case where memory and bodily continuity are lost but identity remains. But: only verificationists conclude that lack of evidence = lack of possibility. So, it remains logically possible that I survive without my body and without my memories. 19 The argument for dualism 1. Let: P = I am conscious and exist in 2003. Q = my body is destroyed in 2003 (end) R = I have a soul in 2003 S = I exist in 2004 2. Whatever else is true today, it is logically possible that P & Q & S. (I.e. (x)(P&Q&S&x), where x ranges over states consistent with P&Q) 3. but if ~R, then (P & Q & S) is not possible. (I.e. ~(P&Q&S&~R)) Therefore: 4. R (I.e., ~R is not within the range of x) 20 The essence of persons So, the form (essential properties) of a person is: The ability to have conscious experiences and perform intentional actions. But what is it for such an essence at T2 to be identical to one at T1? Swinburne: If S2 at T2 has the same form (thought, intention) as that as S1 at T1. And S2 is made out of the same stuff as S1. Then S2 = S1. (Generalized Aristotelian criteria). 21 Mind-body dualism It follows that we are made up of two kinds of stuff. A person is: A thinking thing (soul) combined with A physical body. What matters for survival is the continuation of the soul. Souls are not divisible: All matter takes up space so all matter can be divided (logically) into smaller volumes. Souls take up no space so there is no sense in which they can divide. So, strict identity is preserved. 22 Problems with Dualism According to dualism one’s body, beliefs even personality may change. However: One survives because the soul continues. But: If the soul is not my beliefs, personality or body, what exactly is it? What’s left to be “me”? Is there room in a scientific worldview for an immaterial soul? How can an immaterial substance interact with a material one? 23 Problems with the argument Assume (P & Q & S) is possible. It doesn’t follow that this is only possible if I in fact have a soul. What follows is that this is only possible if it is possible that I have a soul. All Swinburne has shown is that I might have a soul, not that I do. 2. Swinburne assumes that whatever else is true of me, it is possible that I continue to exist without my body. Why assume this? If ~R is true of me right now, then it may not be possible that I continue w/o my body. So the possibility of (P & Q & S) assumes I have a soul, it doesn’t prove it. 24 Appendix: survival and the A-/B-series debate Two views on identity: Endurance: A person is wholly present at each moment s/he exists. The person endures by remaining unchanged from moment to moment (like dualism). Perdurance: A person is extended in time, composed of temporal parts or stages. These parts are related so as to be united into a single whole. There is no one part that is wholly present at all times in a person’s life. Does one’s stance on the A-/B-series dispute constrain one’s position here? 25 Temporal parts and the A-series Argument 1: perdurance is inconsistent with A-time. 1. If X is composed of temporal parts, then there is no time at which all of X’s parts are present. 2. I.e., X can’t be wholly present at different times. 3. So, X can’t “move” in time for this requires all of X to be at T1, then all of X to be at T2, etc. Therefore: 4. If the perdurance view is right, a person can’t “move” through time and the A-series must be false. 26 Objections Objection 1: The perduring whole is present so long as any temporal part is present. I.e., when part P1 is present, the person is (wholly) P1; when P2 is present, the person is (wholly) P2. Reply: Then there is not one thing persisting in time, but two things: P1 and P2. Objection 2: perhaps each part successively becomes present. Reply: then the person is never wholly present at any time, only a part is. 27 Objection 3: Why not say that I am wholly present so long as part of me is. E.g. W.W.II. is present if one of it’s battles is; John is present if one of his parts is. Then, as different parts become present, I (wholly) move in time Reply: If part of me is in room A and part in room B, I am not wholly in either. So, why say that John (or the war) is? 28 Rejoinder: Because time differs from space. If one temporal part is present, we have to say the whole is present—the alternative is absurd: If the whole is past, then no parts are present. If it is future, then no parts are present. So, if a part is present, the whole is neither past nor future. So, it is present if one part is. Reply: This proves too much, i.e. it proves that a whole is past if one part is past: If W is future, no parts are past. If W is present, no parts are past. So, if part is past, then whole is past. Upshot: If perdurance view is right, must adopt the B-series view. To hold to the A-series, one must adopt the endurance view. But … 29 Can the B-theorist be an endurantist? Argument 2: No, she can’t. 1. Assume B-series 2. S is (tenselessly) P 3. S is (tenselessly) not-P 4. So S is P and not-P, which is absurd. Therefore, 5. B-series requires temporal parts to exhibit the different properties. Reply: S is (tenselessly) P at T1 and not-P at T2. I.e. properties are relations if the substance view is right. This is consistent with B-series. So, the B-series is consistent with both endurance and perdurance. The A-series can only have endurance. Is this an advantage for the B-series view (i.e., it rules out less)? 30 Relational vs. substantive time Relational time: time is sets of events standing in temporal relations to each other. Substantive time: time is a substance that contains events. Argument: substance view + B-series view = substantive time. Assume B-time. Assume S is an enduring substance. For all time, S first thinks of Plato (event P) then Descartes (event D). Assume nothing else exists. I.e. all history contains is P followed by D. Every occurrence of P (or D) has exactly the same temporal relations to everything else. So, there is no way to differentiate them. 31 Reply 1: Each is present at a different time. Problems: Abandons B-series for A-series Assumes A-properties occur at different times, and this time might be substantive (i.e. how differentiate them?). Reply 2: Each subsequent P-type event is part of a different stage of S. I.e. we individuate P’s by reference to parts of S. Problem: we have abandoned the endurance view for perdurance. Conclusion: we need substantive time to differentiate the different P (D) events. In other words, different P’s (D’s) are at different substantive points in time. 32 But there is an objection to this: Maybe the story, as told, is incorrect: In fact, there are only two events, P then D (and one substance, S). Since we can’t distinguish them, it follows that we weren’t describing a universe of recurring P’s and D’s. Rather, we were actually describing a universe in which S thinks of P then D, and that’s it. There is no need for substantive time for there are no P’s (D’s) to distinguish. So, relationalism is saved: it is consistent with B-time and endurance (we just need to carefully interpret our stories). But this isn’t the end of the story … 33 Eternal recurrence It may be false, but eternal recurrence seems possible. I.e., there could be a world in which P and D repeat infinitely. So, if we assume S is a substance, and time is tenseless, we must assume: Time is substantive. That is the only way to make sense of different P’s preceding different D’s. I.e., so long as eternal recurrence is possible: The substance view of persons + B-time Entail: Time is a substance. Is this a weakness of the B-series view? 34