CHAPTER THREE - Red and White Kop

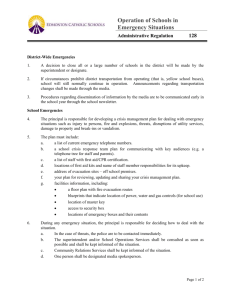

advertisement