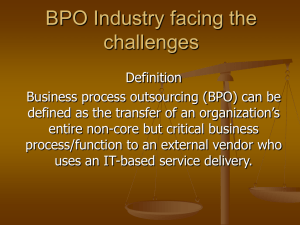

Indo US FTA: Prospects for IT-Enabled/BPO services

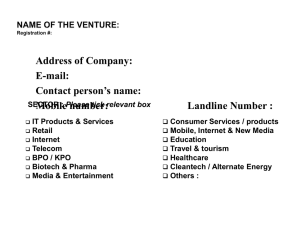

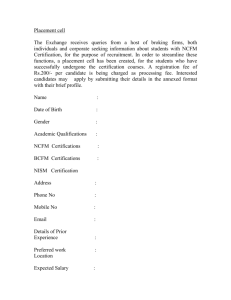

advertisement