Occupation and Identity Construction

advertisement

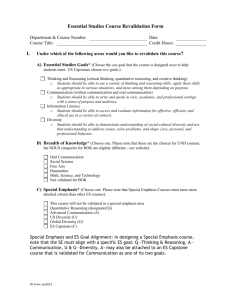

social space matches symbolic space? gendered regional and national identities within a heterogeneous post-war society Renate Huber Paper to be presented in Bo Stråth’s seminar „Writing History, A Collaborative Venture“, 5th November 2001, EUI Florence __________________________________________________________ 2 Dear colleagues and friends, and all others who will read (and hopefully also comment on) this paper, in line with the practises of this seminar, each seminar paper should aim to bring together for discussion both general concepts and more developed concepts, often within a specific setting, as relating to my thesis. Approaching the moment when I will have to write up my PhD, today’s opportunity to present my research to date is a challenge much welcomed. In this paper, I therefore will try to develop the main ideas of my PhD while also trying to set them into a preliminary structure without concluding this process of structuration down by already providing you with a detailed table of contents. The four main parts of this paper, however, will correspond with the main chapters of my PhD – unless you will convince me to restructure my argument. My main objective, of course, is to get as much feedback as possible. As a result, I have not weighted the different sections according to importance to my argument. Instead, I have decided to expose some of the more problematic issues and to present new ideas for critical discussion. Thus, this paper should address some of the main questions and ideas on identity construction processes, discourses on and practises around them as relating to the westernmost province of Austria, called Vorarlberg, with special emphasis on the two decades after the Second World War. Though, the paper will still be fare away from already showing the coherency and straight forwardness I would like to have in my final PhD. For those of you who are not familiar with my research, but who would like to obtain some additional information on its framework, please refer to the seminar paper which I presented some one and a half years ago, also within the context of this seminar.1 While you are reading, possibly struggling through my paper, I am already looking forward to the seminar discussion and your constructive criticisms. 1 [http://www.iue.it/Personal/Strath/Seminars/rewriting2.htm] 3 Bridging and Questioning Theoretical Concepts By choice of this heading, I may also be bridging the way into discussing some of my research dilemmas. As the title of this paper implied, I am dealing with and am interested in a series of different concepts, namely identity, region, nation, gender, occupation, migration, discourse, practice and so on. While I have repeatedly considered to focus on a smaller amount of concepts, I have maintained this comprehensive approach as I believe that the very interesting point about my research is its complexity, is the fact that different identities and their construction processes overlap, fully or only partially, thus constituting a multi-layered identity phenomenon. In order to make this clearer, I will briefly explain how I developed this set of questions. As part of a comparative research project focusing on different historical settings and different regions in Austria, I worked on the perception of ‘the strange’ and ‘strangers’ in post-war Vorarlberg.2 Some clearly marked differences emerged through this comparative approach which I decided to research further. Compared to the province of Salzburg, 3 where the presence of American GIs had been central, in the French-occupied Vorarlberg discourses on the ‘self’ were omnipresent. Interestingly, this ‘self’ was constructed both regionally and nationally (i.e. with regard to Austria), even though the province of Vorarlberg had also been considered federalist, or even separatist. 4 The existence of a strongly marked gender differentiation within these processes had already emerged from the research I had undertaken for my master thesis on women’s everyday life under French occupation in Vorarlberg.5 A considerable amount of my female interviewees had expressed feelings of not having entirely belonged to the post-war society in Vorarlberg, of having felt foreign to a certain extend within their society. My catalogue of questions had contained questions about relationships with occupation soldiers, See Ingrid Bauer/Josef Ehmer/Sylvia Hahn (Ed.), Walz – Migration – Besatzung. Historische Szenarien des Eigenen und des Fremden. Klagenfurt (forthcoming in December 2001) 3 See Ingrid Bauer, ‘Die Amis, die Ausländer und wir’. Zur Erfahrung und Produktion des Eigenen und Fremden im Jahrzehnt nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: see footnote 2. 4 More detailed see Renate Huber, Ein französischer Herr im Haus, ungebetene Gäste und ein Liebäugeln mit den Schweizer Nachbarn. Wahrnehmungen und Deutungsmuster des ‘Fremden’ als Bausteine des ‘Eigenen’ im Nachkriegsjahrzehnt in Vorarlberg, in: see footnote 2. See as well Werner Dreier/Meinrad Pichler, Vergebliches Werben. Mißlungene Vorarlberger Anschlußversuche an die Schweiz und an Schwaben (1918 - 1920), Bregenz 1989. 5 See Renate Huber, ‘I säg all, ma heat vrgessa höra schaffa ... .’ Alltagsleben von Frauen in Vorarlberg während der französischen Besatzungszeit 1945 - 1953 anhand lebensgeschichtlicher Interviews, Phil. Dipl. Salzburg 1996, p. 91ff. 2 4 food, consumer goods, labour market, political and public life, dreams and future perspectives, but none about ‘self’ nor the ‘other’. In a way, new questions developed out of my work, questions that I had not considered before.6 Another phenomenon requiring further investigations had also emerged from my rather inductive research approach. From studying the evolution of the population structure within this province it became evident that due to the unprecedented ‘migration of nations’ as a consequence of the Second World War the immense heterogeneity of the population has to be taken into account. The following graphics7 illustrates on numerical terms the evidence of this phenomenon within the post-war society of Vorarlberg. Indeed, I could focus on one of those phenomena only, using the others as no more than additional explanatory patterns. A balanced analysis, however, would then almost become impossible. One way out of this dilemma could be to analyse these phenomena across different levels, i.e. not a comparison by hierarchy. At this point, I should describe my intended research approach in some further detail. As I already tried to point out, my ideas centre on the 6 Of course, they also show the different time-layers within my research strategy. So, we ourselves are highly bounded to time and to space which also affects the way we are writing our representations on the past, called history. See as well the paper of James Kaye within this seminar session who is developing this point much further than I do in my paper. 7 Land Vorarlberg, eine Dokumentation, verfasst vom Lehrerarbeitskreis des Landes Vorarlberg „Heimatkunde im Unterricht“, Bregenz 1988², p. 36 5 concept of identity, as discussed on a number of occasions in the past, and which I will take for granted in this paper. Region – Nation According to Heinz-Gerhard Haupt, Michael G. Mueller and Stuart Woolf, the relationship between region and nation is “asymmetrical, in the sense that it is impossible to conceive of regional identity without the existence of the nationstate”8. They have argued that the rise of regional identity or regionalism is strongly linked with the increase of the number of phenomena, for instance administrative centralisation, market unification and cultural homogeneity within the nation-state. In general, studies on national identities and nationalism focus either on the period around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century or on the time period after the so-called ‘Wende’ in 1989. The conjunctures of regionalism have more or less followed these trends, or, to be more precise, even seem to have preceded them.9 In line with international trends, a regionalist movement called ‘Pro Vorarlberg’ developed in the late 1970s in Vorarlberg and became subject of research in the 1980s.10 After the Second World War, however, nationalism was disavowed by National Socialism. Thus, it might seem rather contradictory to focus my research on the post-war period which appeared to have lacked the phenomena of regionalism and nationalism. However, analysing identity construction processes from within the cultural studies approach, these implications are changing completely, in particular when introducing the concept of Heimat11 into the analysis. Focusing on a 8 H.-G. Haupt, M. G. Mueller a. S. Woolf (eds.), Regional and National Identities in Europe, p. 11 9 See i.e. Rolf Lindner (ed.), Die Wiederkehr des Regionalen. Über neue Formen kultureller Identität, Frankfurt/New York 1994, p. 7ff. 10 See Markus Barnay, Pro Vorarlberg. Eine Regionalistische Initiative, Bregenz 1983; on regional identity see also Theodor Veiter, Die Identität Vorarlbergs und der Vorarlberger, Wien 1985; Markus Barnay, Die Erfindung des Vorarlbergers. Ethnizitätsbildung und Landesbewußtsein im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Bregenz 1988. 11 See Celia Applegate, A Nation of Provincials. The German Idea of Heimat, Berkeley 1990; Gisela Ecker, ‘Heimat’: Das Elend der unterschlagenen Differenz, in: ib. (ed.), Kein Land in Sicht: Heimat – weiblich?, Munich 1997; Elizabeth Boa/Rachel Palfreyman, Heimat. A German Dream. Regional Loyalties and National Identity in German Culture 1890 – 1990, Oxford/New York 2000. See as well the paper of James Kaye. 6 “society in crisis”,12 as could be applied to Austria in the immediate post-war period, it is difficult to conceive of this post-war society without the term Heimat. On the one hand, the concept of Heimat – which will be more explicitly developed in the paper by James Kaye – may be even more vague than region and nation and therefore even more difficult to utilise. On the other hand, it allows to a further degree the inclusion of cultural practices into explanatory patterns, allowing for a more differentiated analysis and explanation of processes of in- and exclusion. Heimat, in contrast to region and nation, might more inherently implicate the existence of subjectivity and evoke emotionality within negotiation processes relating to questions of belonging and notbelonging. Nonetheless, in my research I do not intend to replace the categories region and nation with the term Heimat. Rather, I would like to connect them through Heimat in the sense that it might facilitate my argument that the relationship between regional and national identities does not have to be competitive (and asymmetrical) by definition, but could be complementary, too. Gender – Region/Nation This rather more elastic approach towards region and nation might help to ‘read’ the identity construction processes in question across different levels, that is to integrate gender. “Nationed Gender and Gendered Nation”13: by choice of using this heading in her introductory chapter on theorizing gender and nation, Nira Yuval-Davis has emphasized the strong references between these two concepts. According to her argument – which I agree with – it is almost impossible to conceive of one of these concepts without taking the other into account. In her article on the relationship between Heimat and Gender, Gisela Ecker has also made a strong case for avoiding isolated analysis of differentiations: “Die Geschlechterdifferenz stellt sich (...) als eine kulturelle Differenzierung unter anderen Differenzierungen dar, und da sie, als isolierte Kategorie analysiert, nur See Bauer, ‘Die Amis, die Ausländer und wir’, Konstrukte und Erfahrungslagen von „selbst“ und „fremd“ im Jahrzehnt nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg: Das Fallbeispiel Salzburg, in: Josef Ehmer/Ingrid Bauer/Sylvia Hahn, Vielfältige und schwierige Fremdheit: Historische Erklärungsszenarien, Salzburg 1998 (unpublished project report), p. 211; ib., in: see footnote 2; See also Stefano Bartolini, Thomas Risse und Bo Stråth, Between Europe and the Nation State: Introduction into the Forum Themes, Seminar Paper EUR/1, 7th October 1999, European Forum, Florence, p. 14f. 13 Nira Yuval-Davis, Gender & Nation, London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi 1997, p. 21 12 7 isoliert Brauchbares zutage fördert, gilt es, die jeweiligen Verschränkungen im System der kulturellen Wertsetzungen zu beachten, als Voraussetzung für eine kritische Intervention.”14 I now would like to return to the strong references between these concepts as they exist on different levels. I here will let the headings of the main chapters in Nira Yuval-Davis’ book speak for themselves: - Women and the Biological Reproduction of the Nation (Volksnation) Cultural Reproduction and Gender Relations (Kulturnation) Citizenship and Difference (Staatsnation) Gendered Militaries, Gendered Wars15 Two aspects appear crucial when linking together both concepts on these different levels: first, the analysis of the male power of definition about what the ‘nation’ (and ‘region’) has (have) been,16 second, how the implementation of the bourgeois family model was embedded into both political discourses on nation (and/or region) and everyday practices. Again, I would argue that there exist quite strong links to the discourses on Heimat. In a workshop on region and gender held in Münster, Sylvia Schraut suggested to investigate the relationship of space and gender in two directions, namely as a male boundary drawing with female limitation/restriction as well as a male boundary preservation with female boundary transgression.17 Her approach exactly corresponds very closely to my own approach, that is to look more closely at how people – women, migrants and ‘occupation children’ in particular18 – were located (through appeal/reference to symbolic space) and positioned themselves within their social space. (The first direction of investigation should be mirrored in the chapter on symbolic space, both directions in the chapter on social space.) Ecker, ‘Heimat, p. 10 See Yuval-Davis, Gender & Nation. 16 I already tried to develop that further in my junepaper (Konstituierungsprozesse regionaler und nationaler Identitäten. Vorarlberg nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, EUI Florence, June 2000.) 17 “Schraut schlug vor, dass ein Modell, in dem Raum und Geschlecht kombiniert wuerden, sowohl die maennliche Grenzziehung mit weiblicher Begrenzung als auch den maennlichen Grenzerhalt mit weiblicher Grenzueberschreitung beruecksichtigen muesse.” See report on the workshop ‘Zum Verhältnis von Geschlechtergeschichte und Regionalgeschichte’, on the 27th June 2001 at Münster, organised by Julia Paulus, [H-SOZ-UKULT@H-NET.MSU.EDU, 29th August 2001] 18 I will develop that further in the chapter on social space. 14 15 8 Migration – Gender – Region/Nation In addition to this multi-level readings of gender and region/ nation, I would like to introduce two further concepts as transversal layers in my research project. Migrants, because of their large number in Vorarlberg – as I attempted to exemplify in my introduction –, cannot be left out this analysis. Indeed, I would even go a step further in my argumentation. The concepts of migration and – see below – occupation, allows us to enquire not only the possibilities of the concepts region/ nation and gender, but also allows us to establish their limits. Identities of migrants are hybrid to a high extend. They are influenced by different symbolic spaces in their every day practices as they commute between different social spaces while potentially oscillating at the same time between various discourses.19 In other words, the space of migrants – in terms of symbols and society – is more and less than the territorially defined space of nations and/or regions. Such immigrants may become in their host country the ‘internal Significant Others’, as Anna Triandafyllidou has pointed out in her forthcoming book on national identities.20 Their common representation as ‘threats’, of course, has influenced the discourses on the ‘self’. With regard to gender, the concept migration might both confirm and limit the explanatory power of similar mechanisms of exclusion, rather than inclusion. It may show the reinforcement of gender differentiation within this national respectively regional context as well as its approximation. Still, the concept itself remains gendered to a very high extend. Migration very often seems to be more or less exclusively a male phenomenon. The corresponding female phenomenon appear merely as non-existing within migrancy.21 Even prototype narratives on migration are male dominated and focussed. One of the most popular narratives – if we agree on the impact of Hollywood movies – is the ‘from-the-dishwasher-to-the-millionaire-story’. This American dream is 19 See Christof Parnreiter, Theorien und Forschungsansätze zu Migration, in: Karl Husa/ib./Irene Stacher (Ed.), Internationale Migration. Die globale Herausforderung des 21. Jahrhunderts?, Frankfurt am Main 2000, p. 30 20 See Anna Triandafyllidou, National Identity Reconsidered. Images of Self and Other in a ‘United’ Europe. Lampeter (forthcoming 2002), manuscript p. 37 21 See Sylvia Hahn, Wie Frauen in der Migrationsgeschichte verloren gingen, in: see footnote 19, p. 77-96; Elisabeth Aufhauser, Migration und Geschlecht: Zur Konstruktion und Rekonstruktion von Weiblichkeit und Männlichkeit in der internationalen Migration, in: see footnote 19, p. 97-122 9 about the ‘self-made man’, of course; a ‘self-made woman’ would be irritating, as it would imply a loss in womanhood, whereas becoming a ‘self-made man’ would agree with an increase of manhood.22 With regard to space, also, there appears to exist a highly gendered connotation of migration, as Gisela Ecker has underlined in her article on discourses on Heimat.23 While the Heimat of the childhood is usually represented as a female space provided with all the attributes of motherhood, the coming back to it is dominated by male actors. Men depart and return, fight in the war, and long for the Heimat, whereas women are supposed to stay, to work and wait, to guarantee its continuity. Apart from these interrelationships between these different concepts, there exists another strong reason for integrating migration into this analysis. As late as in the inter-war period, international migration streams were dominated by Europeans leaving their continent in search of a better life overseas. Only around 1950 did these streams change completely. Indeed, Europe developed from a continent exporting labour into one importing labour.24 This tension was also apparent in the province of Vorarlberg which became both the materialisation of the ‘Golden West’ within Austria as well as the contested place where people ready for emigration got stocked for a while or forever. To leave or to stay: not only does this question still occupy an important place within today’s memories of migrants, but was also influenced by and influenced itself discourses on the ‘self’ in post-war Vorarlberg. Occupation – Gender – (Region/)Nation Occupation is the second concept I wish to introduce as another transversal layer in my work. In general political theory maintains that a nation-state requires sovereignty to exist. As Austria was occupied by four foreign powers from 1945 until 1955, sovereignty was lacking in the first decade after the Second World War. The 22 I tried to develop that idea further in one of the chapters I had to give in at the end of the second year at the EUI (‘Vom Tellerwäscher zum Millionär?’ Gender- und Migrationserfahrungen im Spannungsfeld regionaler und nationaler Selbstverortung, EUI Florence, 2001) 23 See Ecker, ‘Heimat’, p. 12ff. 24 See Douglas S. Massey, Einwanderungspolitik für ein neues Jahrhundert, in: see footnote 19, p. 53-76 10 Austrian nation-state, therefore, only came into existence with the signature of the State Treaty in May 1955. Nonetheless, most academic discourse considers the year 1945 as the crucial turning point in the development of an Austrian national consciousness, which was then reinforced through the 1955 State Treaty.25 At first sight this could appear contradictory. By taking into account that the institution military plays an important role in constituting both nation and gender,26 a second look might provide deeper insights. Though investigations on the relationship between nation, gender and military are usually concerned with the inner-national construction of manhood (respectively womanhood) through military,.27 the application of this relationship can also provide revealing insights into the trans-national construction. The appeal of French (and Moroccan) soldiers for women in Vorarlberg had, for instance, quite often been described through their uniforms, so, through their quality of being soldiers. Apparently, a certain view about the specificity of a soldier-like manhood was part of every day conversation and practices. This phenomenon even was more apparent in interviews conducted within the former American occupation zone. As Ingrid Bauer has concluded from her research on the post-war period in the province of Salzburg,28 local people were both attracted and irritated by the different behaviour of American GIs, as manifested in descriptions of their very different march-steps: Wenn die Amerikaner eine Parade gemacht haben, das war natürlich bei weitem kein so zackiger Schritt. Abgesehen davon, daß sie nicht einmal Nägel an den Schuhen dran gehabt haben, sondern nur Gummisohlen, wo du den Marschtritt ja nicht einmal hörst. (...) Wenn die unten da vorbeimarschiert sind mit ihren kurzen Schritten, so getrappelt, haben wir gesagt: ‚Das ist ja furchtbar.‘ Aber bitte, Sie waren die Sieger.29 25 See i.e. William T. Bluhm, Building an Austrian Nation. The Political Integration of a Western State, New Haven/ London 1973; Ernst Bruckmüller, Nation Österreich. Kulturelles Bewußtsein und gesellschaftlich-politische Prozesse, Vienna 1996; Ruth Wodak et al, Zur diskursiven Konstruktion nationaler Identität, Frankfurt am Main 1998. 26 We have heard about that only recently in the presentation of Thomas Hippler’s paper on the 22nd of October within this seminar. 27 See i.e. Ruth Seifert, Destruktive Konstruktion. Ein Beitrag zur Dekonstruktion des Verhältnisses von Militär, Nation und Geschlecht, in: Erika Haas (Ed.), ‘Verwirrung der Geschlechter’: Dekonstruktion und Feminismus, Munich/Vienna 1995, p. 157-187; Ute Frevert, Soldaten, Staatsbürger. Überlegungen zur historischen Konstruktion von Männlichkeit, in: Thomas Kühne (Ed.), Männergeschichte -–Geschlechtergeschichte. Männlichkeit im Wandel der Moderne, Frankfurt am Main/New York 1996, p. 69-87 28 See Ingrid Bauer, Welcome Ami go home. Die amerikanische Besatzung in Salzburg 1945 1955. Erinnerungslandschaften aus einem Oral-History-Projekt, Salzburg/München 1998; ib., ‘Die Amis, die Ausländer und wir’. 29 Male interviewee, born in 1928, see Bauer, Welcome Ami, p. 98. 11 Sie haben etwas Leichtes, Fröhliches gehabt, schon vom Gang her. Sie haben auch andere Schuhe gehabt als unsere Soldaten, viel leichtere. Ja, sie haben etwas Heiteres und eine gewisse Naivität ausgestrahlt – im Gegensatz zur Schwere unserer Leute. Die sind gerade aus dem Krieg zurückgekommen, abgemagert, fertig. Und die anderen waren – trotzdem sie Militär waren – bubenhaft.30 ‘Die Amis mit ihren Gummischuhen’, hat es immer geheißen. Die deutschen Soldaten haben genagelte Stiefel gehabt.31 Because of their ‘rubber-shoes’, on could not hear their march-steps. Thus, the reception of US soldiers did not match the image constructed in relation to own/ German soldiers.32 Already from the 18th century onwards, discipline became a crucial element within the formation processes of the newly established national mass armies. Through subjecting the male body to military discipline the standardization of a similar male subjectivity increased dramatically. 33 In his paper on military service and national integration at the time of the French Revolution 34 Thomas Hippler has marked out discipline as a tool within military in order to substitute virtue for vice. The description of their gendered dichotomy – virtue as a male and sociable category entailing general interest, vice as a female and anti-social category which is only drawn on as a particular interest – inspired me to develop that idea further within my own research. Virtue appears to be a moral category, whereas vice seems to be immoral on the other. Thus, it might be worth distinguishing in greater detail between discipline and social control in relation to gender. Both tend to limit and punish the individual in order to create a better member of society. Their application, though, seems to mainly coincide with gender differentiations which might well become more visible by focusing on their intended implications. Discipline in particular aims to overcome disobedience, which I would consider being an active concept implying rational controllability. Social control in contrast, as I see it, directs more to prevail over hysteria, a non-rationally based, rather passive concept. Further, I wonder whether this gendered distinction has not have had an impact on the work ethos inherent in the conception of bourgeois life (or possibly also the other way round?). 30 Female interviewee, born in 1930, see Bauer, Welcome Ami, p. 98. Male interviewee, born in 1935, see Bauer, Welcome Ami, p. 99. 32 I think in particular in this relationship between military, nation and gender, the at that time still existing tension between belonging to a German or an Austrian nation becomes very obvious. 33 See Seifert, Dekonstruktive Konstruktion, p. 171ff. 34 See seminar paper ‘Service militaire et intégration nationale pendant la Révolution française’ on the 22nd October 2001, p. 9. 31 12 ***** As my PhD might already contain too many analytical approaches, I will not explicitly reflect on categories like generation, class/milieu, religion, or locality. Even though I will include them occasionally in order to explain certain ideas further. Another methodological difficulty might occur in my PhD. I am not dealing with micro history in the very classic sense, as I am focusing on a whole region and not only on a town or a group of people etc. In other words, even though using a micro historical approach which aims to bring together (all the) different perspectives, I have to choose certain of them within this microcosm. I am going to focus on political discourses on the one hand and social practices within certain groups on the other. I will explain that further in the next chapters. So, I will deal with the problem of how to bring together ‘life’ and ‘text’, as Ernst Langthaler has put it in his workshop paper on memory and identity last April. 35 He has developed a very interesting model for investigating identity construction processes: “We can expect a circular movement, a cultural circuit of encoding, discourse, decoding, and experience (Stuart Hall), which advances in a linear way - as a helix of memory. This helix of memory links together the space of social relations and the space of symbolic relations. By this means some representations achieve more durability and distribution than others; in such a case we speak of cultural representations (Dan Sperber). By cultural representation individuals can take the position of a collective; in such situations individual memories generate a collective memory (Maurice Halbwachs).” Relying on this model which was developed for a local context, I will try to adapt these very useful ideas for my own research on a regional level. I am fully aware of the quite slippery ground beneath the methodological concept of my research project and I might fail in bringing the different perspectives entirely together. One advantage of my approach, however, may be that it might allow to a higher extend to see more precisely the interrelations between the ‘microcosm region’ and the ‘macro history’ not only from a completely asymmetrical perspective.36 35 Ernst Langthaler, The Rise and Fall of a Local Hero. Memory, Identity, and Power in Rural Austria, 1945 – 1960, paper presented in the workshop on ‘Identity and Temporality. Constructions of Continuity and Discontinuity’ organised by Péter Apor, Carsten Humlebæk and myself, 2-3 April 2001, EUI Florence. [http://www.iue.it/Personal/Strath/Colmag/Frames/magset.htm] See as well Ernst Langthaler, Die Erfindung des Gebirgsbauern. Identitätsdiskurse zwischen NS-System und voralpiner Lebenswelt, in: ib./Reinhard Sieder (Ed.), Über die Dörfer. Ländliche Lebenswelten in der Moderne, Vienna 2000, p. 87-142 36 I have already tried to find or create a new term for the fact that region cannot really be considered as a ‘microcosm’. Any suggestions are highly welcome on that issue. 13 Discourses, Agency and Myths – how do Elites Use and Appropriate Symbolic Space “Language in the broad sense, including both symbolic and grammatical codes, exposes a community to a particular experience, to particular ways of constructing the world. Those who control the standardization process derive power from doing so, so that the question of who is able to control the myths of the collectivity is an important one. Those who can invoke myth and establish resonance can mobilize people, exclude others, screen out certain memories, establish solidarity or, indeed, reinforce hierarchy of status and values.”37 By this paragraph, George Schöpflin not only has touched upon very important questions within identity construction processes, but he also has written a wonderful introduction for this following chapter of my PhD. On this account, I will not add that much to the theoretical background of this chapter. Furthermore, I have already developed some main ideas on identity discourses of the political elite in Vorarlberg at the occasion of the workshop on ‘Identity and Temporality. Constructions of Continuity and Discontinuity’ last April.38 Just let me very briefly mention how I intend to structure and develop this chapter. I will mainly focus on the political elite’s attempts to construct identity. But I will not very explicitly focus on the religious and the economical elites nor on the French occupation force within the province as further agencies in these processes as this would go fare beyond the scope of my PhD. Moreover, the provincial governor of the post-war period who was the most important representative of the political elite was a catholic conservative farmer. 39 So, the political discourses will also reflect to a certain extend the discourses of the catholic church the same as certain discourses of the French occupation force who shared this catholic background. For the economical elite, it seems to be a bit different, as she was much more pragmatic in certain respects, but also had to deal with the strong involvement into National Socialism by the majority of their representatives. Sharing the approach of George Schöpflin that language is a very important factor within identity construction processes, I would also like to see these 37 George Schöpflin, The Functions of Myth and a Taxonomy of Myths, in: Geoffrey Hosking/ib. (Ed.), Myths and Nationhood, London 1997, p. 22. 38 Please find attached to this paper the schedule of the ‘Labels of discourses’ which I used for the presentation within this workshop. An extended version of this paper will be publish in a volume on the International Conference in European Studies on ‘Manifestations of National Identity in Modern Europe’, 18-20 May 2001, in Minneapolis. 39 See Ulrich Ilg, Meine Lebenserinnerungen, Dornbirn 1985 14 discourse analysis as an important step towards the linguistic analysis of the interviews in the next chapter. In order to enable myself to inquire into the processes of encoding and decoding – so into the interrelations of symbolic spaces with social spaces –, I will very much focus on the different time-layers within these discourses in the Koselleckian sense of Erinnerungsschleusen and Erfahrungsschichten.40 Practices Embedded into Structures – how do People Experience, Live, and Memorise Social Space According to Uli Bielefeld, the definition of the ‘self’ and the ‘Other’ as well as questions of belonging and not-belonging are negotiated on three different levels, as there are sozialpsychologisch-individuell, politisch-rechtlich and gesellschaftlich-sozial.41 While the first is clearly marked as referring to the inner life of an individual and the second is relying upon structures, the third is what I would sum up by social space plus symbolic space. The last level in a way represents as well the ‘bridge’ between the two others. And of course, analysing a bridge means examining the fundaments on both sides as well as the construction in between. Though there is now doubt about what will be the most interesting part. Thus, that is – metaphorically speaking – how I intend to analyse the interviews. In other words, by keeping the structures in mind and taking the personal predispositions into account, I will mainly focus on how the interviewees placed themselves within their social space within which positions and locations were also symbolically defined. Following the suggestion of Anna Triandafyllidou42 to investigate on Significant Others, I will limit myself to Internal Significant Others who will be women, migrants and so-called ‘occupation-children’. The evidence of the first two groups should already have become clear through my paper. The third group, however, is not significant in the sense that their number was considerably high. Though they were standing for many more encounters than just the one of their parents. And the rhetorics on these encounters were manifold. Furthermore, I consider occupation as an important concept within my 40 See Reinhart Koselleck, Zeitschichten. Studien zur Historik, Frankfurt am Main 2000, p. 265ff. Sorry, these terms cannot be translated. See Uli Bielefeld, Das Konzept des Fremden und die Wirklichkeit des Imaginären, in: ib. (Ed.). Das Eigene und das Fremde. Neuer Rassismus in der Alten Welt?, Hamburg 1991, p. 100. 42 See Triandafyllidou, National Identities Reconsidered, p. 32. 41 15 research. Therefore it might make sense to take the so-called ‘occupationchildren’ in. In order to make it easier to see where people position themselves within their social settings, I have developed the idea to analyse the interviews not as single interviews in the first place, but as fictive group interviews. This idea was highly inspired by the paper “Denkorte: ein Dorf reflektiert sein Gedächtnis” by Bernhard Ecker, Ernst Langthaler and Martin Neubauer.43 In this paper, they have analysed a group interview on how people remember and commemorate the history of a village materialized in a CD-Rom. The actual position of the interviewees – in the spectrum between centre and periphery – was a crucial aspect of this analysis. As this idea is a very recent one, I cannot really tell you whether it will work or not. But considering that individual memory is much more space- rather than time-bounded, as Gabriele Rosenthal has emphasized,44 it should work. Let me use another metaphor. An interview might be described as a walk through the different memory rooms of an interviewee, rooms which have different functions and different symbolic meanings. By opening and (re)closing doors and windows, the interviewee shows the traces of communication between the different rooms. And of course, these memory rooms are not at all deserted. Other people are in very different ways part of them. In this chapter, priority will be given to the analysis of entire biographies in order to get the narrative as a whole. Because of lack of time and as I am already approaching the critical limit of pages for a seminar paper, I will have to leave some examples of these narratives which I have in mind for the seminar discussion. I am sorry for that. Social space matches symbolic space? It is for two reasons that this heading has a question mark. Firstly, I would like to draw your attention to the ambiguity of the term ‘to match’ itself. At first sight it takes the connotation of ‘being equal to or harmonious with something, of corresponding in some essential respect to something else’. Then, of course, the question mark becomes essential for showing that social space did not 43 In: eForum zeitGeschichte 2 (2001) [http://www.eforum-zeitgeschichte.at] See Gabriele Rosenthal, Erlebte und erzählte Lebensgeschichte. Gestalt und Struktur biographischer Selbstbeschreibungen, Frankfurt am Main 1995, p. 78 ff. 44 16 always correspond to symbolic space. With the image of a soccer match in mind, the second meaning – namely ‘to place in conflict, contest, or competition with’ – presents itself. In this case, I could leave the question mark out. Nevertheless, I will leave it there because secondly, I have only some quite vague ideas as to how I should develop this chapter. My intention is to try to ‘confront’ as far as possible – I hope you can even hear the quotation marks – the elites’ discourses with one or even several individual biographies. Or, to be more precise, I should juxtapose single elites’ discourses with some ‘narrationbricks’ out of the interviews. So, I will look whether the discourses intermingle and to what extend they do so, do not so, where not, and why not. I assume that it will not be too difficult to answer ‘where’, whereas I may struggle to answer ‘why’. I think it would be less constructive to copy the structure of the political discourses and of the biographies into this chapter, since this would limit my analytical questions to those aspects which were inherent in the discourses and the experiences, or, in the material as well as in the mental representations.45 Intending to go beyond mere comparison – does social and symbolic space fit, or not – I would like to provide a connection between different functions of identity and how social space matches symbolic space. By formulating these functions as points – that is point of controversy, vanishing point, discussion point, aiming point, integration point –, I may well be able to introduce further clarity to this chapter. I mainly refer to the meanings of a point as the intersection of two lines, as a particular place or position, and as a precise or particular moment. So, do these different functions of identity also generate different attractions of social and symbolic space? Or, do different uses of identity allow us to draw conclusions from the interrelations of symbolic and social space? 45 See the helix of memory. Langthaler, Local Hero. 17 Labels of discourses Resurrection/Rebirth of Austria Discourse on Continuity Reconstruction (Wiederaufbau) Discourse on Dis(continuity) “Schaffa, schaffa, Hüsle baua” Gendered Discourse Liberation – Occupation Discourse on Freedom Denazification Othering of the Germans “Heimatrecht” “Volksgemeinschaft” Citizenship Discourse on Self and Other State Treaty + Neutrality The two Cornerstones of the Austrian Nation Montafon or Montavon Spelling Discourses: Ethnicity vs. Continuity (National) Heroes ... Discourses on Commemorations, Names and Baptism