CHAPTER ELEVEN

advertisement

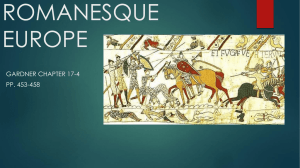

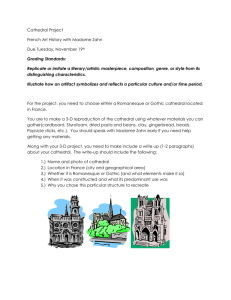

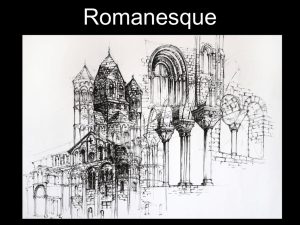

55 CHAPTER ELEVEN ROMANESQUE ART Key Images Nave and choir (looking east), Sant Vincenç, p. 348, 11.1 Lintel of west portal, Saint-Genis-des-Fontaines, France, p. 349, 11.2 Nave, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, p. 351, 11.4 Reliquary casket with symbols of the four Evangelists, p. 352, 11.5 Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, p. 353, 11.7 Nave and choir, Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, p. 353, 11.8 Christ in Majesty (Maiestas Domini), p. 354, 11.9 Cloister, Priory of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, p. 357, 11.13 South portal with Second Coming of Christ on tympanum, Church of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, p. 359, 11.14 Trumeau and jambs, south portal, Church of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, p. 360, 11.16 East flank, south portal, Church of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, p. 360, 11.17 West portal, with Last Judgment by Gislebertus on tympanum, Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, p. 361, 11.18 Gislebertus, Eve, north portal from Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, p. 362, 11.19 Sarcophagus of Doña Sancha, Monastério de las Benedictinas, Jaca, p. 363, 11.20 Christ and Apostles, Priory of Berzé-la-Ville, p. 364, 11.21 Nave, Abbey Church, Fontenay, p. 365, 11.23 Choir, Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, p. 366, 11.24 The Building of the Tower of Babel, Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, p. 366, 11.25 Pentecost, from the Cluny Lectionary, p. 367, 11.26 St. Matthew, from the Codex Colbertinus, p. 367, 11.27 St. Mark, from a Gospel book produced at the Abbey of Corbie, p. 369, 11.28 Initial I, from Gregory the Great’s Moralia in Job, p. 370, 11.29 St. John the Evangelist, from the Gospel Book of Abbot Wedricus, p.370, 11.30 West façade, Notre-Dame-la-Grande, Poitiers, p. 371, 11.31 West façade, Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, p. 372, 11.32 Baptistery, Cathedral, and Campanile, Pisa, p. 372, 11.33 Interior, Pisa Cathedral, p. 373, 11.34 Baptistery of San Giovanni, Florence, p. 374, 11.35 Façade, San Miniato al Monte, Florence, p. 374, 11.36 Renier of Huy, Baptismal Font, p. 375, 11.37 Reconstruction of interior of Speyer Cathedral, p. 376, 11.38 Interior, Speyer Cathedral, p. 376, 11.39 Crowds Gaze in Awe at a Comet as Harold is Told of an Omen, Detail of the Bayeux Tapestry, p. 377, 11.40 The Battle of Hastings, Detail of the Bayeux Tapestry, p. 377, 11.41 Nave, Durham Cathedral, p. 380, 11.43 West façade, Saint-Étienne, Caen, p. 381, 11.46 Nave, Saint-Étienne, p. 381, 11.47 Mouth of Hell, from the Winchester Psalter, p. 382, 11.48 56 Romanesque art, meaning ″in the Roman manner,″ dates from the eleventh to the twelfth centuries in Western Europe. This style of art and architecture was influenced by Carolingian, Byzantine, Islamic, and other artistic traditions. In France, ″pilgrimage type″ churches included a nave, side aisles, transept and apse with radiating chapels. An ambulatory within the apse connected the inner aisles. Vaults are used with interior bay articulations. The interior spatial design of these churches is ″legible″ from the exterior. ″Hall churches,″ without reinforcing arches, offered a continuous surface for interior murals. Innovations in Norman churches include a redefined westwork and a novel interior vault articulation. The cathedral complex at Pisa, the Baptistery of San Giovanni and San Miniato al Monte in Florence reflect the ″classical heritage″of the Tuscan Romanesque style. The revival of monumental stone sculpture during the Romanesque period centered around the entrances to churches. The purpose of this sculpture was to appeal to the lay worshiper. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a member of the Cistercian order which was a reform movement for the Benedictines, objected to the lavish decoration in churches and monasteries. Romanesque sculpture witnessed the use of distinct artistic personalities, such as Giselbertus, Wilgelmo and Antelami. Gislebertus is thought to have trained at Cluny. Figurative Romanesque sculpture included a range of styles from a more ″Roman″ flavor to an intense, nervous linearity which reflects the manuscript and metalwork traditions. The traditions of painting and metalwork during the Romanesque period continued the stylistic energies of Carolingian and Ottonian painting. The Bayeux Tapestry exhibits the same interest in narrative seen in the illuminations of the Gospel Book of Abbot Wedricus. Key Terms/Places/Names apsidioles pilgrimage plan church reliquaries champlevé triforium tympanum 57 trumeau Cistercians Benedictines hall church gable Latin cross groin vaults Bayeux Tapestry Discussion Questions 1. What was the purpose of Romanesque tympanum sculpture? 2. What Classical architectural elements are used in the façade of San Miniato al Monte in Florence? 3. What regional variations are prevalent in the Romanesque Church architecture of Lombardy, Germany and the Low Countries, and Tuscany? 4. In what ways can the Bayeux Tapestry be considered monumental? In what ways is it similar to contemporary manuscript illumination? How is it different? 5. In what ways could the Winchester Psalter be considered instructive? Does it function in the same way as Gislebertus’ Last Judgment? If so, how? Resources Books Busch, Haraldo, and Bernard Lohse. Romanesque Sculpture. London: Barsford, 1962. Gantner, Joseph, and Marvel Pobe. Romanesque Art in France. London: Thames and Hudson, 1956. Grape, Wolfgang. The Bayeux Tapestry: Monument to a Norman Triumph. New York: Prestel, 1994. Petzold, Andreas. Romanesque Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995. Toman, Rolf. Romanesque: The Fascination of Medieval Art from the Mediterranean Lands to Scandinavia. Köln: Könemann, 2005.