8.bronchiectasis

advertisement

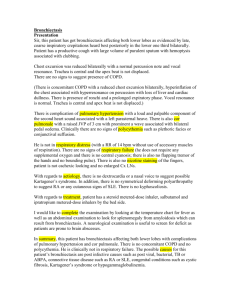

THE KURSK STATE MEDICAL UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SURGICAL DISEASES № 1 BRONCHIECTASIS Information for self-training of English-speaking students The chair of surgical diseases N 1 (Chair-head - prof. S.V.Ivanov) BY ASS. PROFESSOR I.S. IVANOV KURSK-2010 Bronchiectasis Bronchiectasis: Irreversible focal bronchial dilation, usually accompanied by chronic infection and associated with diverse conditions, some congenital or hereditary. Bronchiectasis may be focal and limited to a single segment or lobe of the lung, or it may be widespread and affect multiple lobes in one or both lungs. Etiology and Pathogenesis Congenital bronchiectasis is a rare condition in which the lung periphery fails to develop, resulting in cystic dilation of developed bronchi. Acquired bronchiectasis results from (1) direct bronchial wall destruction--due to infection, inhalation of noxious chemicals, immunologic reactions, or vascular abnormalities that interfere with bronchial nutrition--or (2) mechanical alterations--due to atelectasis or loss of parenchymal volume with increased traction on the walls of airways, leading to bronchial dilation and secondary infection. Bacterial endotoxins and proteases; proteases derived from circulating or pulmonary inflammatory cells; superoxide radicals; and antigen-antibody complexes may mediate bronchial wall damage. Amounts of functionally active neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and neutrophil matrix metalloproteinase MMP-8 found in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid increase with the severity of disease in moderate to severe bronchiectasis. Furthermore, the antiproteases 1-antitrypsin and antichymotrypsin may be proteolytically or oxidatively cleaved into lower molecular weight forms, which provide less protection against enzymatic destruction of extracellular matrix. Detection of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1 ), IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in sputum and demonstration of chemokine and cytokine bronchial cell interactions have led to the hypothesis that such interactions may result in recruitment and activation of certain inflammatory cells, affect their survival, and modulate ongoing inflammation, a cardinal feature of bronchiectasis. Nitric oxide, which affects the immune response, cell signaling, and plasma exudation at inflammatory sites, may help perpetuate the inflammatory response in bronchiectasis. Exhaled nitric oxide is increased in patients with bronchiectasis compared with normal subjects and bronchiectatic patients taking inhaled corticosteroids. Conditions commonly leading to bronchiectasis are severe pneumonia (especially when complicating measles, pertussis, or certain adenovirus infections in children); necrotizing pulmonary infections due to Klebsiella sp, staphylococci, influenza virus, fungi, mycobacteria, and, rarely, mycoplasmas; and bronchial obstruction from any cause (eg, foreign body, enlarged lymph nodes, mucus inspissation, lung cancer, or other lung tumor). Miscellaneous chronic fibrosing lung diseases (eg, those following aspiration pneumonia or inhalation of injurious gases or particles-eg, silica, talc, or bakelite) also predispose to bronchiectasis. Immunologic deficiencies, including AIDS, and various other acquired, congenital, and hereditary abnormalities that increase host susceptibility to infection or impair respiratory defenses are less common but important predisposing factors. Although incidence and mortality have decreased with the widespread use of antibiotics and immunizations in children, bronchiectasis as a manifestation of cystic fibrosis is still common. (Cystic fibrosis (mucoviscidosis; fibrocystic disease of the pancreas; pancreatic cystic fibrosis): An inherited disease of the exocrine glands, primarily affecting the GI and respiratory systems, and usually characterized by COPD, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and abnormally high sweat electrolytes). Bronchiectasis, along with situs inversus and sinusitis, is a feature of Kartagener's syndrome, a subgroup of the primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) syndromes. In these syndromes, structural or functional abnormalities in ciliary organelles result in defective mucociliary clearance that leads to suppurative bronchial infections and bronchiectasis as well as chronic rhinitis, serous otitis media, male sterility, corneal abnormalities, sinus headaches, and a poor sense of smell. Bronchiectasis can occur in patients with Young syndrome, which is characterized by obstructive azoospermia, chronic sinopulmonary infections, normal spermatogenesis, a dilated epididymal head filled with spermatozoa, and amorphous material without spermatozoa in the region of the corpus. Absent are the ciliary abnormalities seen in the PCD syndromes, the genetic and electrolyte abnormalities characteristic of cystic fibrosis, and the genetic mutations found in congenital absence of the vas deferens, which accounts for about 6% of obstructive azoospermia. An unusual pattern of bronchiectasis occurs in allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (An allergic reaction to Aspergillus fumigatus occurring in asthmatic patients as eosinophilic pneumonia): The proximal bronchi are dilated rather than the medium-sized subsegmental or peripheral bronchi as in idiopathic bronchiectasis. Bronchial wall damage is thought to be due to an immunologic response to a colonizing protease-producing fungus, most commonly Aspergillus fumigatus, permitting the organism to persist and inflammation and destruction to continue. The reported association of bronchiectasis with probable or possible autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and ulcerative colitis, has not been satisfactorily explained. Pathophysiology Bronchiectasis may be unilateral or bilateral; it is most common in the lower lobes, although the right middle lobe and lingular portion of the left upper lobe are often affected. The traditional classification as cylindrical, varicose, or saccular is based on the pathologic and bronchographic appearance. However, these distinctions have little clinical value, and current pathologic correlations with high-resolution and helical CT characteristics are making this classification obsolete. Pathologically, bronchial walls show extensive inflammatory destruction, chronic inflammation, increased mucus, and loss of cilia. Where adjacent interstitial and alveolar areas are destroyed, tissue reorganization and fibrosis result in loss of volume. Bronchiectasis is generally associated with chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema and some fibrosis. The extent and character of the pathologic changes determine the functional and hemodynamic abnormalities, which often include reduced lung volumes and airflow rates, ventilation/perfusion defects, and hypoxemia. Extensive anastomoses between the bronchial and pulmonary arteries may occur, with marked enlargement of bronchial arteries. Anastomoses between bronchial and pulmonary veins also enlarge. The resultant increased blood flow, right-to-left shunts, and hypoxemia lead to pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale late in the disease. CLASSIFICATION 1. unilateral, bilateral, total damage. 2. cylindrical,saccular and mixed bronhiectasis 3. anatomic localization (nomber of the lobe, etc) 4. with or without complications CLINICO-ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION 1.the first stage – cylindrical bronhiectasis, are localized in basal segments of lungs, unilateral damage. Tretment – conservative. 2.the second stage – cylindrical and saccular bronhiectasis, unilateral damage. Treatment – conservative and surgical treatment (segmentectomy, lobectomy, pulmonectomy- if there are no contraindications) 3/the third stage – saccular, bilateral bronhiectasis. Symptomatic conservative treatment. Symptoms and Signs Bronchiectasis, which can develop at any age, begins most often in early childhood, but symptoms may not be apparent until much later. Their severity and characteristics vary widely from patient to patient and from time to time in an individual, depending largely on the extent of the disease and the presence and extent of complicating chronic infection. Most patients have chronic cough and sputum production--the most characteristic and common symptoms--but occasionally, a patient is asymptomatic. These symptoms often begin insidiously, usually after a respiratory infection, and tend to worsen gradually over a period of years. Severe pneumonia with incomplete clearing of symptoms and residual persistent cough and sputum production is a common mode of onset. As the condition progresses, the cough tends to become more productive. Typically, it occurs regularly in the morning on arising, late in the afternoon, and on retiring; many patients are relatively free of cough during the intervening hours. Sputum usually is similar to that of bronchitis and is not characteristic. Less commonly, in long-standing cases, sputum is abundant and may separate into three layers: frothy at the top, greenish and turbid in the middle, and thick with pus at the bottom. Hemoptysis from erosion of capillaries, but sometimes from anastomoses between the bronchial and pulmonary arterial systems, is common and may be the first and only complaint. Recurrent fever or pleuritic pain, with or without visible pneumonia, is also common; investigation of such symptoms may lead to the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. Wheezing, shortness of breath and other manifestations of respiratory insufficiency, and cor pulmonale (Heart failure (congestive heart failure): Symptomatic myocardial dysfunction resulting in a characteristic pattern of hemodynamic, renal, and neurohormonal responses) may occur in advanced cases with associated chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Physical findings are nonspecific, but persistent crackles over any part of the lungs suggest bronchiectasis. Signs of airflow obstruction (decreased breath sounds, prolonged expiration, or wheezing) tend to be more pronounced in smokers than in nonsmokers. Finger clubbing sometimes occurs with extensive disease and persistent chronic infection (Measuring finger clubbing. The ratio of the anteroposterior diameter of the finger at the nail bed (a-b) to that at the distal interphalangeal joint (c-d) is a simple measurement of finger clubbing. It can be obtained readily and reproducibly with calipers. If the ratio is > 1, clubbing is present. Clubbing is also characterized by loss of the normal angle at the nail bed). Diagnosis Bronchiectasis must be suspected in anyone with the above symptoms and signs. Standard chest x-rays may show increased bronchovascular markings from peribronchial fibrosis and intrabronchial secretions, crowding from an atelectatic lung, tram lines (parallel lines outlining dilated bronchi due to peribronchial inflammation and fibrosis), areas of honeycombing, or cystic areas with or without fluid levels, but occasionally x-rays are normal. High-resolution CT (HRCT) of the chest (1- to 2-mm cuts) has largely replaced bronchography. With 10-mm collimation, dilation of small bronchi may be missed, but the better resolution of HRCT provides results comparable or preferable to bronchography. Its widespread use indicates that bronchiectasis is probably more common than can be diagnosed by clinical findings and standard x-rays alone. Characteristic CT findings are dilated airways, indicated by tram lines, by a signet ring appearance with a luminal diameter > 1.5 times that of the adjacent vessel in cross section, or by grapelike clusters in more severely affected areas. These dilated medium-sized bronchi may extend almost to the pleura because of the destruction of lung parenchyma. Thickening of the bronchial walls, obstruction of airways (evidenced by opacification--eg, from a mucus plug--or by air trapping), and, sometimes, consolidation are other findings. Helical CT may be considered for surgical candidates because at least one study has shown it to be superior to HRCT in identifying the extent of bronchiectasis and distribution within a given segment, but the additional radiation exposure has prevented it from supplanting HRCT for general use. HRCT may be performed with or without contrast; the precise protocol is tailored to the patient's clinical situation. Excessive secretions or blood in the bronchial tree or acute bronchopneumonia can lead to misinterpretation. The reversible dilation that occurs with airspace consolidation (eg, pneumonia) should not be confused with true bronchiectasis. Chronic bronchitis often accompanies and may mimic bronchiectasis, but recurrent hemoptysis, fever, and pleuritic pain and the x-ray abnormalities help distinguish bronchiectasis from chronic bronchitis alone. Mycobacterial and fungal infections should be ruled out, because they are treatable. Sputum cultures, bronchial washings, serologic studies for fungal antigen or antibodies, and even biopsy of appropriate tissue (but not highly vascular bronchiectatic airways) may be indicated. When CT reveals multiple small nodules with bronchiectasis in a nonimmunocompromised host without cystic fibrosis, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAIC) cultures are commonly positive, and in some patients, MAIC granulomas suggest disease rather than mere colonization. When disease is unilateral or of recent onset, fiberoptic bronchoscopy is indicated to rule out tumor, foreign body, or other localized endobronchial abnormality. HRCT is often performed first to provide maximum information to the bronchoscopist in advance, but bronchoscopy is usually still necessary for precise pathologic diagnosis. Associated conditions should be sought, particularly cystic fibrosis, immune deficiencies, and predisposing congenital abnormalities. Such a search is most important in symptomatic younger patients and in patients with particularly severe or frequently recurring infections. Cystic fibrosis should be suspected if the abnormalities on x-ray occur predominantly in the apices or upper lobes. Pancreatic insufficiency is a feature in children but is not common in adults, in whom pulmonary manifestations predominate. Diagnosis of cystic fibrosis is based on sweat test results (Cystic fibrosis (mucoviscidosis; fibrocystic disease of the pancreas; pancreatic cystic fibrosis): An inherited disease of the exocrine glands, primarily affecting the GI and respiratory systems, and usually characterized by COPD, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and abnormally high sweat electrolytes.). Genetic testing may be informative in fertile patients who have unexplained bronchiectasis with normal pancreatic function and sweat electrolytes. Young syndrome, more common than cystic fibrosis or PCD syndromes, should be suspected in men with chronic recurrent sinopulmonary symptoms and infertility. Normal spermatozoa, testicular function, and sweat test results distinguish it from typical cystic fibrosis or PCD syndromes. Some patients with vas deferens abnormality have mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene, but such mutations have not yet been demonstrated in those with Young syndrome. PCD syndromes occur in 11% of children with chronic respiratory disease. Diagnosis is confirmed by examining the ultrastructure and function (motility, beat frequency) of nasal or other respiratory cilia, obtained via biopsy or brushing, and by measuring nasal ciliary clearance time--the time it takes for a patient to first taste saccharin after it is instilled above the inferior turbinate of the nose (normal: 12 to 15 min). Interpreting ciliary abnormalities involves excluding nonspecific ciliary defects, which can be present in <= 10% of cilia in patients with acquired pulmonary disease and in healthy persons; recognizing that infection can cause transient dyskinesia; and being aware that ciliary characteristics of patients and healthy persons can overlap. Ciliary ultrastructure may be normal in patients with PCD syndromes, perhaps because of biochemical and molecular abnormalities that affect function but not ultrastructure. Immunoglobulin (Ig) deficiencies may be identified by serum Ig measurements. If serum protein electrophoresis detects low -globulin levels, serum IgG, IgA, and IgM should be measured. Even when total levels of IgG or IgA are normal, some IgG subclass deficiencies have been associated with sinopulmonary infections; IgG subclasses should be measured in patients with unexplained bronchiectasis. 1- Antitrypsin ( 1-antiprotease inhibitor) deficiency, which is occasionally associated with bronchiectasis, may be suspected when 1-globulin is low and may be confirmed by phenotyping with crossed immunoelectrophoresis. Congenital abnormalities of tracheal or bronchial cartilage and connective tissue are usually detected on x-ray. In tracheobronchomegaly (Mounier-Kuhn syndrome), the trachea is about twice as wide as normal. In the rare WilliamsCampbell syndrome, total or partial absence of cartilage beyond the main segmental bronchi produces wheezing and dyspnea early in infancy; bronchoscopy, CT, or newer imaging techniques may show inspiratory ballooning and expiratory collapse of the affected bronchi. The yellow nail syndrome, believed to be due to a congenital hypoplasia of the lymphatic system, is recognized by thickened, curved, yellowish to greenish nails and primary lymphedema. Some patients have exudative pleural effusion and bronchiectasis. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis may be suspected when there is a wheal and flare reaction to fungal antigens, serum IgE is high, serum precipitins for Aspergillus fumigatus or another fungus are elevated, and the clinical picture suggests it. Blood and sputum eosinophilia are often present. Prophylaxis Awareness and early identification of conditions frequently associated with bronchiectasis may permit earlier therapy that may prevent its development or reduce its severity. More than half the cases of pediatric bronchiectasis can be accurately diagnosed and promptly managed to lessen morbidity. When there is a family history of cystic fibrosis, prenatal diagnosis by DNA analysis to identify specific mutations may permit very early treatment and guide counseling. Childhood immunization against pertussis and measles, widespread use of antibiotics, and improved living conditions and nutrition have helped reduce the prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of bronchiectasis. Influenza vaccine yearly and pneumococcal vaccine one time (or repeated after 6 yr for persons at particular risk and likely to respond) may be helpful and are increasing in clinical importance. Early treatment of respiratory syncytial virus infection with ribavirin aerosol and prompt treatment of pneumonia may lessen their damaging potential. Appropriate treatment of pneumonia is based on the age of the patient, presence of comorbidities, severity of the infection, probable source, and likely pathogens. Ig replacement in deficiency states, early detection and removal of foreign bodies and localized bronchial obstructions, treatment of recurrent sinusitis, and prevention and prompt treatment of conditions predisposing to aspiration of infected or toxic material may prevent repeated chest infections or damage that leads to bronchiectasis. Ig replacement, reported to reduce the number and severity of chest infections in Ig deficiency states, may be especially beneficial in patients with a documented impairment in antibody production after a specific challenge. Immune globulin is given IM in doses sufficient to maintain an infection-free state. IV immune globulin (IVIG) is also available. Trough levels of serum IgG > 500 mg/dL are associated with fewer infections and better pulmonary function than are lower levels. IVIG may do more than passively supply antibody. It may neutralize some bacteria-derived toxins or otherwise supplement host anti-inflammatory defenses. Dose and frequency must be tailored to the patient. Inhalation of noxious gases and particulates, including cigarette smoke, should be avoided or minimized by using effective environmental controls or personal protective devices. When acute inhalation injury occurs, prompt treatment of complicating infection and judicious use of a corticosteroid may reduce inflammatory damage. Treatment Treatment is directed against infections, secretions, airway obstruction, and complications (eg, hemoptysis, hypoxemia, respiratory failure, cor pulmonale). Treatment of infection includes antibiotics, bronchodilators, and physical therapy to promote bronchial drainage. Sputum usually contains gram-positive and gramnegative microorganisms (eg, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Moraxella [Branhamella] catarrhalis, Pseudomonas sp); anaerobes commonly inhabit bronchiectatic cysts. A broad-spectrum antibiotic (eg, ampicillin 250 to 500 mg po q 6 h for adults or 50 to 100 mg/kg/day in divided doses q 6 to 8 h for children, with a maximum dose of 2 to 3 g/day for large children; amoxicillin 250 to 500 mg po q 8 h for adults or 40 mg/kg/day in divided doses for children; or, only for adults, tetracycline 250 to 500 mg po q 6 h) is often used until the sputum is nonpurulent and less voluminous, about 1 to 2 wk. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) 320/1600 mg po q 12 h for 14 days can also reduce sputum volume and eliminate pathogens; for children, TMP-SMX 6/30 to 12/60 mg/kg/day is given in divided doses q 12 h, depending on the size of the child and severity of the infection. Tetracycline or trimethoprim can inhibit increased airway absorption of sodium in vitro and might have a double benefit in a disease such as cystic fibrosis, in which enhanced sodium absorption in the airways is believed to contribute to inspissated secretions. A newer macrolide, such as clarithromycin or azithromycin, or a 2nd-generation cephalosporin is another possible choice. Antibiotics should be repeated at the first sign of recurring infection (eg, increased volume or purulence of sputum). If infection recurs often, prolonged chemoprophylaxis with ampicillin, amoxicillin, or tetracycline may be tried but is generally disappointing. In severe cases, high-dose amoxicillin (3 g po bid) is reported to achieve higher serum and sputum concentrations than do equal doses of ampicillin. Prophylactic or suppressive antimicrobial regimens can reduce the bacterial load (associated with purulence and destructive elastase activity in some), but there is no consensus about long-term continuous versus intermittent therapy or about specific regimens. With short-term therapy (1 to 2 wk), purulence and elastase activity rapidly return to pretreatment levels. One goal is to prevent development of resistant microorganisms and conditions favoring Pseudomonas sp, which is particularly difficult to eradicate. Regimens include an oral antibiotic for 7 to 10 days each mo, 7 to 10 days of treatment alternating with equal rest periods, continuous long-term treatment with a reduced dose, or high doses of an antibiotic (such as amoxicillin) for 3 to 6 mo. A fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin 500 to 750 mg po bid, may be effective and can be given long-term, but resistance frequently develops after one or two treatment cycles. In severe cases, aerosol or IV regimens may be needed, but resistance is always a problem. Alternating drugs may help avoid early resistance and persistence of pneumococci, which tends to occur with ciprofloxacin. For bronchopneumonia or serious respiratory infection, parenteral antibiotics-chosen on the basis of Gram stain, cultures, and sensitivity studies--are indicated. Cefuroxime 750 mg IV tid for 48 to 72 h followed by cefuroxime axetil 500 mg po bid for 5 days is as effective as amoxicillin 1.2 g IV tid with clavulanic acid followed by amoxicillin 625 mg po tid. Amoxicillin penetrates lung secretions, especially in the presence of active inflammation, but some local inactivation may occur, correlating with -lactamase levels. For broader coverage to include Mycoplasma, Legionella, and Pseudomonas sp, a macrolide plus a 3rd-generation cephalosporin (such as ceftazidime or cefoperazone) plus an aminoglycoside can be used, or piperacillin or azlocillin with an aminoglycoside can be used when Pseudomonas predominates. When cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis are positive, appropriate antituberculosis treatment is required based on the clinical history and laboratory findings, but MAIC commonly colonizes the lungs of patients with bronchiectasis, so treatment is reserved for patients with strongly suspected or proven disease. An empirical multidrug regimen for MAIC may include clarithromycin 500 mg po bid, ethambutol 25 mg/kg po daily, clofazimine 200 mg po daily, and streptomycin 10 to 12 mg/kg/day IM or amikacin 12 to 15 mg/kg IM three times a week for 1 to 2 mo, followed by clarithromycin 750 mg po daily, ethambutol 15 mg/kg po daily, and clofazimine 50 to 100 mg po daily for 3 to 24 mo, usually given until cultures are negative for 12 mo. Basing therapy on drug susceptibility testing, however, is important. Patients with bronchiectasis should avoid cigarette smoke and other irritants and refrain from using sedatives or antitussives. Postural drainage, clapping, and vibration performed regularly may facilitate sputum clearance in some patients. Diffuse chronic bronchitis, often accompanying bronchiectasis, should be treated accordingly. 2-Agonists, theophylline, and corticosteroids may decrease airflow obstruction, facilitate ciliary clearance, and reduce inflammation. If asthma or allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is also present, corticosteroids may be especially beneficial in reducing inflammation, and in young children, who are most susceptible to fungal sensitization, they may enhance fungal elimination. Itraconazole 200 to 400 mg/day po reduces the corticosteroid requirements, reduces serum IgE, and improves airflow rates in a small number of patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, but antifungal drugs are usually reserved for invasive Aspergillus infection. Other drugs--such as the mucolytic N-acetylcysteine and recombinant human deoxyribonuclease (rhDNase), which breaks down DNA in purulent sputum--may benefit selected patients but have no proven benefit in bronchiectasis. NSAIDs, such as indomethacin, have been tried experimentally. Despite mild reduction in sputum volume and changes in peripheral neutrophil function, sputum elastase and myeloperoxidase levels were not reduced, and viable bacterial load was not altered in bronchial secretions. Chronic hypoxemia should be treated with O2, particularly if the PaO2 in a stable patient is < 55 mm Hg on room air or if there is evidence of pulmonary hypertension or secondary polycythemia. Respiratory failure and cor pulmonale should be treated as in other patients with chronic obstructive airway disorders. Intubation and mechanical ventilation should, if possible, be avoided, because the ability to cough is lost and the risk of inadequately evacuating secretions by suctioning alone and of promoting further infection is enhanced. Lung transplantation can be performed in patients with advanced cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. Double lung transplantation is usually the procedure of choice. Surgical resection is rarely necessary but should be considered when conservative management yields to recurrent pneumonia, disabling bronchial infections, or frequent hemoptysis and the disease is sufficiently localized and stable. For massive pulmonary hemorrhage, emergency resection or embolization of the bleeding vessel (usually a bronchial artery) can be lifesaving.