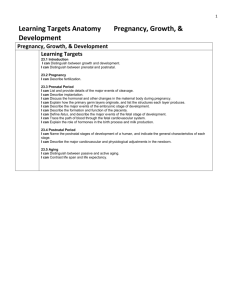

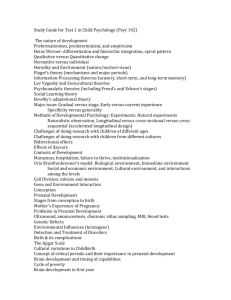

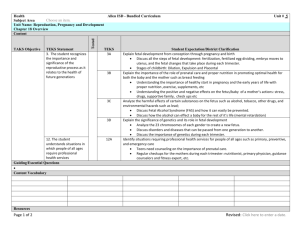

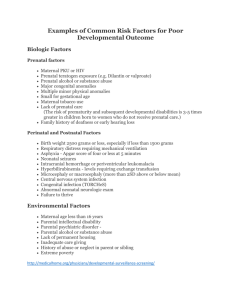

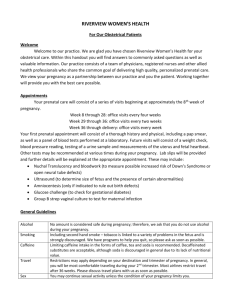

Prenatal Section

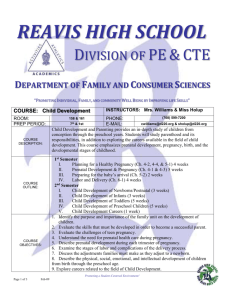

advertisement