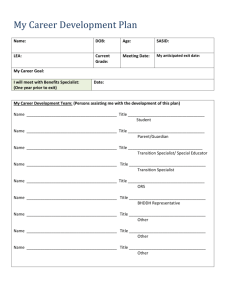

Review of the Standards for the Regulation of Vocational Education

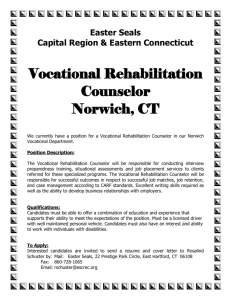

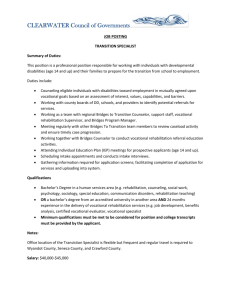

advertisement