Lecture 1

advertisement

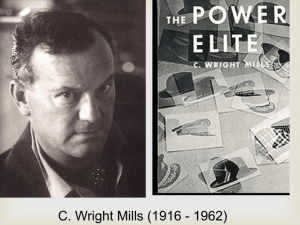

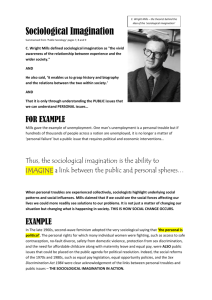

Understanding Contemporary Society Lecture and Seminar Programme Lecture 1 Understanding contemporary society This lecture explores what makes social scientific knowledge distinctive. It will address the difference between social science and common sense, define what the American sociologist C. Wright Mills termed “the sociological imagination”, and encourage students to think about their experiences at university in social scientific terms. Seminar Reading and Preparation - Read the brief extracts below from C. Wright Mills on the sociological imagination, the first chapter of Bauman and May and the introductory chapter of any sociology textbook. How might you apply these ideas to your own life and to social issues that concern you? How might you begin to understand your first week at university in sociological terms? What does it mean to “think sociologically”? What distinguishes social science from common sense? Further reading Wright Mills, C. (1970) [1959] The Sociological Imagination, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Bauman, Z. and May, T. (2001) Thinking Sociologically, 2nd ed. Blackwell: Oxford. (Ch. 1) Berger, P. (1966) Invitation to Sociology, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Abercrombie, N. (2004) Sociology, Cambridge: Polity Press. Back, L. (2007) The Art of Listening, Oxford: Berg. Bauman, Z. (2000) ‘Sociological Enlightenment – For Whom, About What?’, Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 71-82. Fuller, S. (2006) The New Sociological Imagination, London: Sage. Highmore, B. (2009) A Passion for Cultural Studies, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Jenkins, R. (2002) Foundations of Sociology, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan The January assessment requires you to review an academic journal article, so it would be a good idea early on to begin to learn how to find and read academic journal articles. This piece will give you an idea of how sociologists take an everyday phenomenon and use sociological theory and methods to make sense of it. Journal articles like this are available in hard copy in the library, but also electronically via the E-Library Gateway. Green, E. and Singleton, C. (2009) “Mobile connections: an exploration of the place of mobile phones in friendship relations”, Sociological Review, Vol. 57, No. 1, pp. 125 – 144 Quotations from C. Wright Mills (1970) [1959] The Sociological Imagination, Harmondsworth: Penguin 1. The sociological imagination defined “The sociological imagination enables its possessor to understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals” (Wright Mills 1970: 11). “The first fruit of this imagination – and the first lessons of the social science that embodies it – is the idea that the individual can understand his own experience and gauge his own fate only by locating himself within his period, that he can know his own chances in life only by becoming aware of those all individuals in his circumstances” (Wright Mills 1970: 12). “No social study that does not come back to the problems of biography, of history, and of their intersections within a society, has completed its intellectual journey” (Wright Mills 1970: 12). 2. The distinction between personal troubles and public issues “Perhaps the most fruitful distinction with which the sociological imagination works is between ‘the personal troubles of milieu’ and ‘the public issues of social structure’. This distinction is an essential too of the sociological imagination and a feature of all classic work in social science. Troubles occur within the character of the individual and within the range of his immediate relations with others; they have to do with his self and with those limited areas of social life of which he is directly and personally aware (…) Issues have to do with matters that transcend these local environments of the individual and the range of his inner life. They have to do with the organization of many such milieux into the institutions of a historical society as a whole, with the ways in which various milieux overlap and interpenetrate to form the larger structure of social and historical life (…) In these terms, consider unemployment. When, in a city of 100,000 only one man is unemployed, that is his personal trouble (…) But when in a nation of 50 million employees, 15 million men are unemployed, that is an issue, and we may not hope to find its solution within the range of opportunities open to any one individual. The very structure of opportunities has collapsed. Both the correct statement of the problem and the range of possible solutions require us to consider the economic and political institutions of the society, and not merely the personal situation and character of a scatter of individuals” (Wright Mills 1970: 14-15).