ENGL 301 Definitions edited

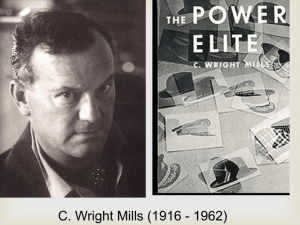

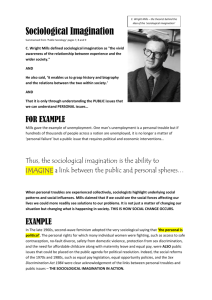

advertisement

The objective of this assignment is to practice our skills in writing definitions of complex terms for an audience without previous knowledge in the area. There will be three sets of definitions for the term. The types of definitions include the parenthetical, sentence, and expanded definition. For this exercise, I have chosen the term “Sociological Imagination”, which is a very common term in my study of Sociology. However, for a person outside of this major, they may not fully understand the meaning of this term. Therefore, these definitions will be targeted towards an audience who are novices to the area of Sociology. 1. Parenthetical definition: Through the sociological imagination (concept on the ability to link the relationship between individuals and greater forces of influence from society), we can see the relationship between suicide rates and the geography. 2. Sentence definition: Coined by C. Wright Mills, the sociological imagination is the ability to situate personal troubles and life trajectories within an informed framework of larger social processes. 3. Expanded definition: How was this created? A Sociologist, C. Wright Mills, published the book ‘Sociological Imagination’ in 1959 in which the concept on the ability to link the relationship between impacts of a large-scale social force and those of individuals was explored. Figure 1: The illustration in figure 1 demonstrates how the individual is influenced by much larger forces outside of their personal lives. It lists examples of these possible influences such as family, work, religion, to even greater scopes such as sexism, homophobia, racism, and classism. Image source: https://thesociologicalperspective.wordpress.com/kick-ass-college/criticalthinking/core-sociological-concepts/ What does it do? This concept allows the individual to see his or her issue beyond that of their daily lives, and instead, understand it from a sociological perspective. What is our relationship with the Sociological Imagination? As individuals, it is common that we cannot see far beyond the scopes of our daily lives, nor past the close perimeter about us. We see our personal problems simply as individual struggles. Unemployed? You need to work harder. Feeling fat? You need to be skinnier. From the smallest details of our lives to life-changing decisions, it may never appear to go beyond what is our own biography. However, the ‘sociological imagination’ explains that by making connections between these personal issues to that of the public, we can better understand how these social forces subsist among our daily lives. By doing so, we can see how it may be that not only is it an individual problem, but a problem shared with many others as a public issue. This ability, stated by C. Wright Mills, is a significant part of the sociological perspective. Figure 2: Figure 2 demonstrates how feeling depressed may be linked to capitalism. It seems odd to trace the cause of your depression to capitalism; however, it shows how even everyday problems like these for individuals may be influenced by forces much greater than we thought possible. Image Source: https://s-media-cacheak0.pinimg.com/236x/fa/26/76/fa2676d661e080045de838b66ae26ecd.jpg Why the Sociological Imagination? It is believed by Mills that “neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both”. (Mills, 1959) Furthermore, He describes individuals to be lacking in the awareness of the “interplay of individuals and society, of biography and history, of self and world”. (Mills, 1959) Thus, the capability to grasp this link is vital as to empowering the individual to see that their biography is a contribution to history of society. Sources: Boundless. “The Sociological Imagination.” Boundless Sociology. Boundless, 21 Jul. 2015. C. Wright Mills (1959). The Promise, in The Sociological Imagination (Chap. 1). New York: Oxford Univ. Press. Levkowitz, . H. (2013, October). CHOICE, 50(2). Retrieved September 27, 2015. Morozov, E. (2011, June 10). The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2015