Esoteric Libraries

Esoteric Libraries

by Albert R. Vogeler

“Esoterica.” As a category of literature in libraries, or on dusty shelves of usedbook shops, the word implies books that are rare, obscure, secret, faintly sinister, perverse, delusional, unintelligible, and connected to rites, magic, and cults. “Esoterica”--which can be more or less equated with “hermetica” and “arcana”-- does indeed claim to embody hidden knowledge of great significance--life-transforming secrets--which are accessible only through guided insight and spiritual training. The implied distaste, suspicion, and dismissal of esoteric literature today is of course a modern rational response to a vast body of texts in many languages, some with a long history of influence, veneration, and deep study in both

Western and Eastern cultures.

In concentrated collections, esoterica has historically comprised whole independent libraries, as distinct from recent specialized collections of esoterica within general libraries.

An esoteric library has always been tangible: a collection of books. But today it may also be virtual: a collection of titles on a computer screen. The jarring fact about esoteric libraries is that many have websites. Some are apparently nothing but websites. We cannot easily know how many esoteric groups are not on line. But those that are on line apparently have no qualms about self-advertisement. For any library, the transformation of books from a physical to a virtual existence is--at least for the older generation—miraculous and even discomfiting. But for an esoteric library it creates what the critics call “cognitive dissonance.”

Secrecy, privacy, and spirituality seem blatantly inconsistent with a public presentation promoting promiscuous access.

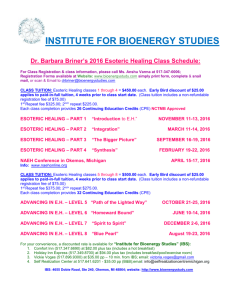

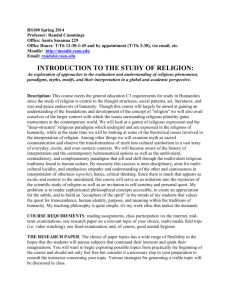

On-line esoteric libraries are usually more than lists of titles. Books may be excerpted, and in some cases full texts can be summoned up; background and commentary

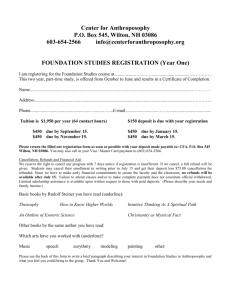

(as on a DVD) may be provided; and links establish new connections. The esoteric teachings of Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and Rosicrucianism are notable for their displays of important documents. But each presents itself initially as an educational, therapeutic, or selfhelp program promoting ethics and the good life; and each veils or defers mention of its metaphysical substructure, cross-cult connections, and internal power struggles. Continuity

with ancient traditions and relevance to modern life are both stressed; co-fraternity with

and differences from other esoteric groups have to be shown; the difficulty and the promise of grasping hidden truths have to be balanced.

Esoteric libraries consisting of real books are not necessarily in remote places: some may be found in the heart of modern civilization. People who have, or want to have, direct conversation with the dead, or who puzzle over ghosts, poltergeists, or precognition should know the immense treasure-trove of published testimony on these subjects in a building on a quiet London street. There, the Society for Psychical Research, a survival of the Victorian fascination with spiritualism, soldiers on in a skeptical age. So does the Swedenborg

Society in Bloomsbury, dedicated to perpetuating the grandiose cosmological vision of the eighteenth-century Swedish mystic. And the Rosicrucians (Ancient and Mystical Order

Rosae Crucis) maintain a religious compound in San Jose with a library, planetarium, and

Egyptian museum all testifying to the heterogeneous esoteric sources of the Order.

Esoteric libraries of alchemy, astrology, witchcraft, and magic may have disturbing associations: remember, in Harry Potter, how the Hogwarts Library’s thick volume of powerful incantations burst suddenly into flames when it was opened by an unqualified reader?

By

distilling elixirs, casting spells, and reading horoscopes, Masters and adepts gain secret knowledge that supposedly permits powerful interventions in the natural order. At the extreme limits of Tantrism, Yoga, Kabbala, and Sufism (all well represented in websites) paranormal events purportedly accompany enlightenment. For believers, libraries of esoteric books represent reservoirs of concentrated spiritual energy waiting to be tapped.

Some people assume that Theosophy is a venerable esoteric tradition—but it was invented in New York only in 1875 by Madame Helena Blavatsky. Its authoritative works, many of which are on its internet library, hark back to ancient traditions, primarily Hindu, but are also elaborate inventions of its prolific founder (the website lists her seven books and provides the texts of 238 of her articles). There are in fact several Theosophical websites competing for authenticity and members. (The doctrines, schisms, and politics of the movement are recounted in a top-notch scholarly journal published at Cal State Fullerton and edited by James Santucci of the Comparative Religion Department: Theosophical History.)

One of Theosophy’s esoteric teachings, the coming of a new messiah or World

Teacher, led to Jiddu Krishnamurti’s acceptance of this exalted role, which he then renounced in 1928. During the next six decades, he practiced as an independent guru, rejecting the name but fulfilling the role, in the process creating a new persona and a new body of esoteric literature to be found on the Krishnamurti Foundation website.

The books of secret teaching of Eckancar, the esoteric science of soul flight, are on its website. If, after years of devoted study, you become an adept, you can hope to travel fast and free—no fare, no luggage—and no body. Fortunately, or unfortunately, your destination must be on a higher plane of existence, not Hawaii, and illumination, not relaxation, will be your reward.

Scientology, whose origins in 1950s pop culture are obvious, provides a website in which the “ library of Scientology” begins with a dozen science fiction pulp novels by L.

Ron Hubbard. In its aggressive growth from Dianetics into a “Church”--always reliant on secret teachings needing increasingly advanced interpretation, and expanding costs and commitments—it purveys its primal myths at a price, and gains a cultural presence through influential converts like Tom Cruise.

Thelema, a contemporary outgrowth of the obsessive confabulations of Aleister

Crowley a century ago, offers a vast website library of Crowley’s orphic utterances. His notorious “Abbey of Theleme” in Sicily, shut down by Mussolini, provides the inspiration of modern Thelemites in its motto, “Do what thou wilt shall be the sum of the law.” Not license, they insist on their website, but freedom and fulfillment, are their aims. A surprisingly large number of local branches, including one in Laguna Hills, invite you to participate.

The highly-evolved Masonic Orders do not present themselves to the public primarily as esoteric institutions, but their roots run deep in the occult world, their symbols and nomenclature reflect it, and their libraries expound it. Mormons, accommodating to much of modern life, nevertheless have their origins in Freemasonry and occultism, and

share secret books and hidden ceremonies with esoteric cults, along with sacerdotal hierarchies, changing revelations, suppressed practices, sacralized mythologies, and costly membership. The websites of most New Age religions also testify to their esoteric heritage.

. If esoterica puts you off, or makes you impatient and bewildered, the antidote may easily be found. A refreshingly different kind of institution, dedicated to sweeping away mental cobwebs, has recently appeared on Hollywood Boulevard. The Center for Inquiry

West (sponsored by the Council on Secular Humanism and the Committee for the Scientific

Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal) is devoted to promoting critical thinking, scientific method, and liberal social values. There are other Centers of Inquiry around the country. These people are tenacious skeptics, rationalists, debunkers, and practitioners of open debate. Their library serves their cause of mental liberation. How much more antiesoteric can you be?