Allergy Care Pathways Project: Anaphylaxis Working Group

advertisement

Allergy Care Pathways Project

Anaphylaxis Pathway – final draft v16

Table of Contents

National Care Pathway ...........................................................................................................................1

Anaphylaxis ............................................................................................................................................1

Methodology ...........................................................................................................................................3

Recommendations .................................................................................................................................7

Research Priorities .................................................................................................................................8

Care Pathway for Children with Anaphylaxis .......................................................................................9

Conflict of interest ................................................................................................................................15

References ............................................................................................................................................16

Appendix 1: Glossary...........................................................................................................................20

Appendix 2: Evidence Table: systematic reviews and primary research .........................................21

Appendix 3: Evidence Table: Guidelines ............................................................................................27

National Care Pathway

Allergic conditions constitute the commonest cause of chronic disease in childhood and affect upwards

of 20% of the population. They seriously impair quality of life and health of children and occasionally

can lead to death. Children and young people who experience allergic conditions often received

different levels of care which can affect health outcomes and interfere with schooling. The 2006

Department of Health review of allergy services recommended that there was a specific need to define

care pathways for children with allergic conditions.

The terminology and format for care pathways is wide and varied. Critical pathways, care paths, clinical

pathways are all patient focussed tools that provide the sequence and timing of actions to achieve

patient outcomes with the greatest efficiency [20]. Integrated care pathways are important because they

help to reduce unnecessary variations in patient care and outcomes [21].

The RCPCH has been commissioned by the Department of Health to develop 6 national care pathways

for children with allergies. It is the intention of the Project Board to develop ideal evidence based

national care pathways that are adopted for local use. These pathways will focus on standardising the

level of care received by children with allergic conditions and defining the competences required to

provide a high quality service.

The Allergy Care Pathways Project Board recommends that all locally adopted care pathways should be

implemented by a multidisciplinary care team with a focus on improving services for children with

allergic conditions. One important factor in implementing the care pathway is the use of audit tools to

analyse unnecessary variations in care.

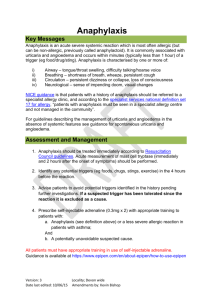

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, generalised or systemic hypersensitivity reaction which is

characterised by rapidly developing life-threatening respiratory and/or circulation problems; it is usually

associated with skin and mucosal changes [22;23].

Understanding the epidemiology and disease burden posed by anaphylaxis is important in order to

develop insights into risk factors for its aetiology, and inform service provision and resource allocation

decisions. Accurately characterising the epidemiology of anaphylaxis is however complicated by

inconsistencies in disease definition [23] and the challenges in undertaking prospective cohort studies for

a disorder that is relatively infrequent, and in which disease episodes are typically short-lived and are in

the majority of cases self-limiting [24]. There is as a consequence concern about under-reporting,

Page 1

v15

under-recognition and under-diagnosis of anaphylaxis, this further complicating any reliable assessment

of its frequency or impact. This is important because despite the overall good prognosis, fatalities do

occur, most commonly in young people; these fatalities are believed to be largely avoidable with

appropriate emergency and preventative management [24-29].

A variety of data sources have been used in an attempt to estimate the incidence, lifetime prevalence,

morbidity and case fatality ratio associated with anaphylaxis. These have included population surveys,

case records from primary and secondary care, hospital episode statistics, adrenaline prescribing data

and mortality statistics. Whilst all these available sources have some utility, population-based studies are

likely to yield the most accurate data on the epidemiology and disease burden posed by anaphylaxis.

From the population-based data currently available, the incidence rate, where this is defined as the

number of episodes of anaphylaxis that occur in a defined population over a given period of time, is

estimated at between 80-210 episodes per million person-years [24]. Incidence varies by age, gender,

geography and socio-economic position; the usual socioeconomic gradient between adverse health

outcomes and deprivation seems to be reversed [30]. The limited data available on time trends suggests

that the incidence of anaphylaxis has increased over recent decades and this appears in particular to be

due to increases in allergies to foods in children and young people and adverse drug reactions in older

people; greater awareness, recognition, reporting and recording are other possible explanations [30-36].

Anaphylaxis may be triggered by a wide range of factors, but may also occur spontaneously (idiopathic

anaphylaxis). The most common trigger in childhood is food, followed by drug allergy. Anaphylaxis due

to other triggers such as insect venom or exercise is rare [33;37]. The most frequent food triggers in

childhood are peanut and nuts, cows milk, hen egg, fish and shellfish [38;39].

Lifetime prevalence can be defined as the proportion of a defined population known to have experienced

anaphylaxis during their lifetime. A review by a Working Group of the American College of Allergy,

Asthma and Immunology summarised the findings from a number of seminal studies and concluded that

anaphylaxis affects anywhere between 0.05-2.0% of the general population at some point in their lives,

these large variations possibly reflect regional differences in the diagnostic criteria that tend to be used

[40]. More recent work from the UK however suggests that the prevalence in the UK may be lower than

this estimate; interrogation of a large database of GP records suggests that there are an estimated

40,000 people with a clinician-recorded diagnosis of anaphylaxis diagnosis in the UK [35].

The majority of episodes of anaphylaxis are self-managed by patients/carers – often sub-optimally using

antihistamines and/or bronchodilators, but not adrenaline – and many people experiencing episodes of

anaphylaxis will therefore not receive medical attention [41]. A proportion of episodes will result in the

seeking of medical attention, of whom some (estimated at 28-100 hospital admissions per million people

per year) will be admitted to hospital [24;42].

As a potentially fatal condition, anaphylaxis can have a profound impact on quality of life, this impact

extending way beyond the acute phase of the illness. Although still often thought of mainly as an acute

disorder, anaphylaxis should really be considered as a long-term condition [26]. The impact on the

quality of life of carers should not be under-estimated.

There are at present no reliable ways of assessing of who will and will not experience severe episodes,

but in general terms factors such as the speed of onset of the reaction, the dose of allergen required to

trigger a reaction and severe previous reactions are markers of potentially severe future reactions [27].

Those with underlying asthma – especially if poorly controlled – and cardiovascular disease are

particularly at risk of fatal outcomes [24-27;43]. Delay in receiving medical attention and in particular

adrenaline treatment is another key factor that has repeatedly been implicated in fatal episodes [44;45].

The overall case fatality ratio, where this is defined as the proportion of cases of anaphylaxis that prove

Page 2

v15

fatal of anaphylaxis, is estimated at less than 1% in the majority of case series, or in population terms as

between 1-5.5 fatal episodes of anaphylaxis per million population per year [24]. Mortality statistics

obtained for the Department of Health review showed that from 1993 to 2002 there were approximately

10 deaths per year in England and Wales in which anaphylaxis was a contributing cause [46]. Reported

anaphylaxis fatality rates will inevitably underestimate the true incidence due to difficulties in diagnosis

post-mortem. A case review of death certificates for adults and children in the UK recorded up to 20

probable anaphylactic deaths in the UK annually [47].

Methodology

Objectives

The aim of the project was to develop an evidence-based national care pathway for children with

anaphylaxis. The underpinning principle was that the eventual pathway would:

describe the ideal pathway of care for children from the first presentation with suspected

anaphylaxis in any healthcare setting to the desired patient endpoint

be informed by the best available research evidence and, in areas where research evidence is

lacking, by the consensus of a multidisciplinary team of experts

define the steps in pathway on the basis of the competencies of health care professionals rather

than the setting in which the care should be provided

provide a national template to facilitate local review of services for children with anaphylaxis to

ensure consistent high quality care.

Stages of Pathway Development

The pathway was developed by a multi-disciplinary Anaphylaxis Working Group (AWG) chaired by Dr

Andrew Clark and which reported to a Project Board chaired by Professor John Warner.

The AWG included health professionals with expertise in paediatric allergy, allergy nursing, pharmacy,

primary care, secondary care, immunology, dietetics and emergency care and a parent/carer

representative (Table 3). The AWG was supported by a full-time project manager.

There were two face-to-face meetings of the AWG, in September and October 2009 and one telephone

conference in November 2009.

1. Initial mapping

At its initial meeting the AWG mapped out the ideal care pathway for the five key stages: self care,

ambulance care, emergency department (ED) care, inpatient/further care and outpatient

management, including follow up.

2. Evidence Review

A comprehensive evidence review was undertaken to identify the evidence base for a care pathway

for children with anaphylaxis. A PICOS (Patient/Population, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes

and Studies) approach was used when formulating the search strategy.

Scoping search

An initial scoping search conducted between 3 August and 25 August 2009 focussed on clinical

questions did not provide a comprehensive list of evidence. The full list of clinical questions used in

the clinical questions used in the scoping search can be obtained from the RCPCH Science &

Page 3

v15

Research Department. This strategy was not pursued and a general systematic search for the

overall care of children with allergies was undertaken.

Literature search strategy

A systematic search was conducted between 26 and 27 August 2009; this covered searches in the

Cochrane Library, Medline, the National Guidelines Clearing House, the Scottish Intercollegiate

Network (SIGN) and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). An updated final search

will be conducted upon completion of all of the pathways in July 2010.

Search terms were compiled by pearling expert identified papers for keywords. The terms identified

and used included: hypersensitivity, adolescen$, child$, infant and anaphylaxis. A copy of the full

search strategy can be obtained from the RCPCH Science & Research Department. The search was

not restricted by language. In order to collate the most contemporary evidence base the search was

restricted to the period 1 January 1990 – 26 August 2009. The results of the search were compiled in

a Reference Manager library to allow for easy identification of duplicates. There was no systematic

attempt to identify grey literature. Additional papers for inclusion were identified by snowballing the

references of the appraised papers. Handsearching was conducted by working group members.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Participants: Children and young people aged 0-18 with anaphylaxis and/or an allergic condition

related to anaphylaxis. Mixed studies were included where it was possible to extract data on children

and young people. Where there was no evidence directly relating to children adult studies were

included on the recommendation of expert opinion, otherwise adult studies were excluded.

Interventions: Studies that included preventative and therapeutic interventions in any setting by any

health professional, including self care.

Comparators: Any comparator, including no comparator.

Outcome measures: The outcomes examined in the review of evidence included symptoms

(mild/moderate/severe), quality of life and mortality.

Studies: Systematic reviews of key interventions and clinical guidelines/guidance based on reviews

of evidence were included. Primary research was considered, including RCTs, non-controlled trials,

case-control studies and cohort studies. Case reviews with more than 3 reports were also considered

where there was no other evidence.

Evidence Appraisal Methods

The evidence was appraised in 3 stages: an initial title review, an abstract and title review and finally

an appraisal.

Stage 1

The project manager initially reviewed 831 titles; this resulted in 199 systematic reviews, primary

papers and guidelines.

Abstracts and titles were then reviewed by the AWG Chair; this resulted in 37 systematic reviews

and/or primary papers and 6 guidelines for appraisal by the AWG members.

Stage 2

Stage 1 was conducted by the AWG Chair who reviewed the 199 titles and abstracts of the clinical

guidelines and papers using 3 measures: meets study criteria (e.g. anaphylaxis), concerned

with/applicable to children and young people and guideline, systematic review or primary research

with original data.

Page 4

v15

This process resulted in 37 systematic reviews and/or primary papers and 6 guidelines for appraisal

by the AWG members

Stage 3 – systematic reviews and primary research

Thirty seven systematic reviews and primary research passing stage 1 and 2 were critically

appraised by two reviewers from the AWG using modified Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP)

tools [48]. The CASP tools can be obtained from the RCPCH Science & Research Department.

Data extraction was performed concurrently with the critical appraisal. Conflicts were resolved using

de-identified appraisals and the consensus of the AWG members. All included papers were

synthesised into an evidence table and assigned an evidence level by the AWG according to the

SIGN methodology (Table 1) [49].

This process resulted in the inclusion of 12 papers and an additional 17 papers for review through

snowballing the reference lists. After the completion of the stage 3 appraisal of the systematic

reviews and primary research 19 papers were marked for inclusion.

Stage 3 – guidelines

All documents setting clinical standards and passing stage 1 and 2 were reviewed by the RCPCH

Clinical Standards Team to ensure College standards for endorsement were met as part of the

RCPCH appraisal and endorsement process. One component of this was to appraise the guideline

using a modified version of the AGREE tool [50]. Any methodological weaknesses were highlighted

in the evidence tables and all included guidelines were assigned an appropriate grade accordingly.

Due to time and resource constraints within the project design recommendations from the clinical

guidelines have been accepted verbatim. Methodological weaknesses of each clinical guideline

were highlighted in the evidence table (Table 5).

This process resulted in the inclusion of 4 clinical guidelines. All but one clinical guideline appraised

used the SIGN methodology (Table 2) to grade their recommendations. The Resuscitation Council

UK Guideline [51] used the RCP Concise Guidance to Good Practice [52]; this is highlighted in the

evidence table.

Table 1 Key to evidence statements [49]

Level

Criteria

1++

High quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a very low risk of bias

1+

Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a low risk of bias

1-

Meta-analyses, systematic reviews, or RCTs with a high risk of bias

2++

High quality systematic reviews of case control or cohort or studies

High quality case control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high

probability that the relationship is causal

2+

Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a

moderate probability that the relationship is causal

2-

Case control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that

the relationship is not causal

3

Non-analytic studies, e.g. case reports, case series

4

Expert opinion

Page 5

v15

Figure 1: Methodology of Evidence Review

Literature Review and Expert Opinion

Project Manager

Stage 1: Reference Manager (de-duplication)

[831]

Project Manager

Titles reviewed

[199]

Project Manager/WG Chair

Titles and Abstracts reviewed [43]

Snowballing

reference list of

appraised papers

[17]

WG members

Include [12]

Stage 2:

Guidelines

[6]

Systematic Review/

Primary Evidence:

Stage 2 [37]

RCPCH Clinical Standards Team

WG Chair

Exclude {5}

Include [23]

Include

[4]

Exclude {14}

Exclude

{2}

Critical Appraisal / Data

extraction: Stage 2

Critical Appraisal / Data

extraction: Stage 3

Stage 3:

AGREE

Appraisal

Project Manager, background (5)

WG members, background (5)

RCPCH Clinical Standards Team

Include [7]

Exclude {0}

Include [12]

Exclude {6}

Include [4]

Exclude

{0}

Project Manager

Data extraction

Table 2 Grades of Recommendation [49]

Grade

A

Criteria

At least one meta-analysis, systematic review, or RCT rated as 1++, and directly applicable to the

target population; or

A body of evidence consisting principally of studies rated as 1+, directly applicable to the target

population, and demonstrating overall consistency of results

B

A body of evidence including studies rated as 2++, directly applicable to the target population,

and demonstrating overall consistency of results; or

Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 1++ or 1+

C

A body of evidence including studies rated as 2+, directly applicable to the target population and

demonstrating overall consistency of results; or

Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2++

D

Evidence level 3 or 4; or

Extrapolated evidence from studies rated as 2+

3. Synthesis of Pathway

Defining the pathway

The pathway was developed over two meetings of the AWG. At the first meeting the pathway was

iteratively mapped using expert consensus opinion. This process was initiated by defining the

principal points of entry into the pathway of children with anaphylaxis and then breaking down the

ideal pathway of care into discrete stages from self-care to follow -up. For each of these stages a

number of key components of care were identified. This approach was further developed at the

second meeting using the results of the evidence review to guide the discussion. The pathway

stages were further developed and linked, where possible, to the strength of the evidence, using

colour coding to distinguish those stages underpinned by evidence and those informed by the expert

opinion of the group. The pathway is colour coded according to the assigned SIGN grade [49].

Page 6

v15

Defining the competences

Competences were mapped to the appropriate section of the pathway using three sources:

RCPCH: A Framework of Competences for Level 3 Training in Paediatric Immunology,

Infectious Diseases and Allergy [53]

RCPCH: A Framework of Competences for Training General Paediatricians with an interest in

allergy [54]

Skills for Health National Occupational Standards for Allergy [55]

For each stage of the pathway the group then identified the competencies in one or more of the three

main categories:

the things a health professional should know

the specific skills a health professional should be able to do

the services or facilities the health professional should have access to

The final pathway is in therefore in two sections; an algorithm of the stages of care of the ideal

pathway and the competences, with the evidence referenced, required to deliver the ideal pathway.

4. Stakeholder consultation/External peer review

An initial stakeholder list was constructed by the Project Board. All stakeholders were contacted by

email and invited to review the pathway. Stakeholders were also invited to suggest additional

stakeholders. The pathway document was also made available on a public section of the RCPCH

website between Tuesday 6 October and Thursday 22 October, 2009. All stakeholder comments

were made public on the RCPCH website upon finalisation of the pathway and a full list of the

comments are available from the RCPCH Science & Research Department.

2. Development of recommendations

The AWG recognises that care pathways are not clinical guidelines and therefore do not normally

include recommendations. However the review of the evidence in relation to children with

anaphylaxis led the group to identify 4 key evidence-based recommendations which the group felt it

was important to include in the pathway chapter.

While the SIGN methodology allows for recommendations to be graded the AWG has chosen not to

do this. The evidence table clearly states the evidence levels applied to each paper. A full list of

evidence statements leading to the recommendations can be obtained from the RCPCH Science &

Research Department.

Recommendations

The Anaphylaxis Working Group (AWG) makes 4 key recommendations:

1. Prompt administration of adrenaline by intramuscular injection is the cornerstone of therapy both in

the hospital and in the community.

2. Children and young people at risk of anaphylaxis should be referred to clinics with specialist

competence in paediatric allergies.

3. Risk analysis should be performed for all patients with suspected anaphylaxis.

4. Provision of a management plan may reduce the frequency and severity of further reactions and is a

recommended part of anaphylaxis management.

Page 7

v15

Research Priorities

See: \\filesvr02\research$\RESEARCH\CURRENT PROJECTS\Allergy care

pathways\MEETINGS\Project Board\20091123_Meeting 3\Anaphylaxis Research Priorities.doc

Page 8

v15

Care Pathway for Children with Anaphylaxis

Entry points

Public places

Early years settings

School

Work

Further & Higher education

Home

Family

Self Care

GP/Primary Care

Immunisation clinic

Hospitals

NHS Direct/NHS 24

Emergency 999

i. Recognition that the child is seriously unwell

ii. An early call for help

iii. Early administration of IM injectable adrenaline, if indicated and available

iv. Identification and removal of trigger, if possible

1

Ambulance

Service/

Primary Care2

i. Recognition that the child is seriously unwell

ii. Initial assessment and treatments based on an ABCDE approach

iii. Early administration of IM injectable adrenaline, if indicated and available

iv. Transfer to Emergency Department (ED)

v. Other treatment, if necessary

ED: initial care3

i. Recognition that the child is seriously unwell

ii. Initial assessment and treatments based on an ABCDE approach

iii. Adrenaline therapy if indicated

i. Further treatment, observation and history

ii. Record all possible anaphylaxis triggers

iii. Provide adrenaline injector

iv. Train in use of adrenaline injector

v. Allergy clinic referral

vi. Provide basic avoidance advice

vii. Provide patient group information

ED/inpatient:

further care4

Medical Care5

i. Allergy focussed clinical history and examination5a

ii. Onward referral, if required5b

iii. Undertake investigations5c

iv. Identify trigger and exclude non-relevant triggers5d

v. Risk assessment5e

vi. Assess and optimise management of other allergies5f

vii. Provide trigger avoidance advice5g

viii. Provide dietary advice5h

ix: Communication5i

x. Immunotherapy, if indicated5j

Outpatient

management,

including follow

up

Provide an emergency management package6

i. Provide appropriate emergency medication

ii. Provide emergency treatment plan for future anaphylactic reactions

iii. Train to use emergency medication

School and early years settings care (SEYS)7

i. Adequate SEYS liaison

ii. Train in recognition of anaphylaxis and avoidance of identified trigger

iii. Provide training in the use emergency medication

Provide follow-up care8

i. Review diagnosis and update avoidance advice

ii. Update emergency treatment plan

iii. Repeat school training

GRADE A

Page 9

GRADE B

GRADE C

GRADE D

WORKING GROUP CONSENSUS

v15

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening, generalised or systemic hypersensitivity reaction which is likely

when all of the following 3 criteria are met:

1. Sudden onset and rapid progression of symptoms

2. Life-threatening airway and/or breathing and/or circulation problems

3. Skin and/or mucosal changes (flushing, urticaria, angioedema)

Ideally all specialists will have paediatric training in line with the principles outlined in the Children's

National Service Framework (NSF) [56].

Children is an inclusive term that refers to children and young people (0-18years).

A specialist allergy clinic is defined by the competences laid out in this document.

The pathway is linear but it is important to recognise the entry points can occur at any part of the

pathway and that the pathway children follow may not be linear.

All deaths from suspected anaphylaxis should be recorded on a National Anaphylaxis Register.

Ref

1

Pathway stage

Self Care

2

Ambulance Service /

Primary Care

3

ED: initial care

4

ED /inpatients further care

5

Medical Care

Page 10

Competence

Know

the signs and symptoms of potential anaphylaxis

to call for help

when and how to administer injectable adrenaline, if indicated

and available

to identify and remove the trigger, if possible

Know:

the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis

to transfer to the ED in all cases

Be able to

make an initial assessment and treatment based on an ABCDE

approach [51]

administer injectable adrenaline, if indicated

identify and remove the trigger, if possible

provide other treatment, if necessary

Know:

the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis

Be able to

make an initial assessment and treatment based on an ABCDE

[51]

administer injectable adrenaline, if indicated

Know

to record any suspected trigger(s)

to observe the patient, ideally for 4-6 hours, and understand the

potential for biphasic reactions

to refer to an allergy clinic [57-60] directly, via the GP using a local

clinic or by checking the BSACI website

Be able to

provide ongoing observation and treatment of the episode

provide basic avoidance advice based on the suspected

trigger(s)

provide and train in the use of an adrenaline injector

provide access to patient/parent/carer support group information

This is best provided by a multidisciplinary team including allergy

specialist doctors, specialist nurse(s), paediatric dieticians and

appropriate school nurse liaison for the further management of

v15

Ref

Pathway stage

5a.

Clinical history and

examination

5b

Referral

5c

Investigation – all allergies

5d

Investigation – drug and

venom allergy

Page 11

Competence

children with anaphylaxis [58-61]

Be able to

recognise and distinguish the features of anaphylaxis from less

severe allergic reactions

recognise the clinical features of conditions which masquerade

as anaphylaxis (e.g. panic attacks, vocal cord dysfunction,

hereditary angioedema)

recognise that anaphylaxis can present as ‘asthma’ without any

cutaneous or other features

gather relevant information on exposure to potential triggers (e.g.

anaesthetic chart for GA anaphylaxis)

recognise the clinical features of anaphylaxis induced by

different triggers and appreciate important differences (e.g.

food, venom, drug, exercise induced and idiopathic)

take a full history including important co-morbidities (e.g.

asthma) and psychosocial issues and interpret the findings

examine and interpret findings in relevant body systems

including chest, ENT and skin

Know

to refer children with venom, drug allergy, idiopathic and

exercise induced anaphylaxis to specialist units with appropriate

expertise in investigation and management

to refer onwards if you do not have access to the appropriate

range of diagnostic techniques (refer to boxes 8. and 9.

investigation) or knowledge of their indications, limitations and

interpretation [45;57;58;60]

when to refer to other agencies, e.g. CAMHS

Have access to:

sufficient facilities, practical skill and knowledge to undertake

and interpret investigations including

– mast cell tryptase (know the time course of elevation during

anaphylaxis) [59]

– skin prick testing [59]

– serum specific IgE

– for food allergy - facilities to perform and interpret oral

challenges in a safe and controlled environment

Understand the

relationship between sensitisation and clinical allergy

performance (sensitivity and specificity) of tests for sensitisation

to allergens which commonly cause anaphylaxis

Know

which allergies commonly occur together in the same individual

(e.g. latex and kiwi fruit allergies) and therefore which additional

tests should be performed

that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) allergy

tests, including kinesiology, serum specific IgG and Vega tests

have no place in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis

Be able to

interpret the results of investigations in the context of the clinical

history

Have access to

sufficient facilities, practical skill and knowledge to undertake

and interpret investigations including facilities to perform and

interpret (in a controlled and safe environment) [59]:

– intradermal tests for venom and drug anaphylaxis

– oral or subcutaneous challenges for drug allergy. For venom

v15

Ref

Pathway stage

5e

Identify trigger

5f

Risk Assessment [62]

5g

Assess and optimise

management of other

allergies

5h

Provide trigger avoidance

advice for family members

5i

Provide dietary advice

Page 12

Competence

allergy, understand potential cross reactivity between species

and the relative value of serum specific IgE and skin tests

For drug allergy be able to

exclude allergy to alternative related drugs (e.g. antibiotics and

anaesthetics)

Be able to

synthesise information gathered from history, examination and

diagnostic tests to identify the likely trigger factor

exclude non-relevant triggers which the patient may be

inappropriately avoiding

Know

the natural history of individual food allergies, venom, drug,

exercise induced, and food and exercise induced anaphylaxis to

be able to provide the patient with a reasonable risk assessment

indicating the likelihood of further anaphylactic episodes and the

need for provision of emergency medication

Be able to

recognise potential high risk situations and provide appropriate

advice to minimise the risk

Be able to

appreciate the importance of maintaining good asthma control in

children with anaphylaxis

assess asthma control using history, examination and

investigations (including spirometry)

identify allergic and non-allergic triggers for asthma

recognise that rhinitis control affects asthma and treat

appropriately

give written and verbal advice on reducing allergic triggers

prescribe asthma medication appropriately

provide a written emergency management plan for asthma as

required

Have the relevant skills and information to educate and empower

families on avoidance strategies including

food allergy: be able to provide comprehensive written and

verbal advice based on knowledge of the natural history of the

food allergy and the age of the child. Also, be able to provide

sufficient information to interpret labelling on food and non-food

products.

drug allergy: be able to provide written and verbal advice on

which specific drugs to avoid (main trigger and any crossreacting drugs). Also, the ability to inform the family which drugs

can be tolerated in future.

Venom: be able to provide advice to reduce chance of further

stings including practical measures and information on cross

reacting species.

For exercise induced and food and exercise induced

anaphylaxis be able to provide written and verbal advice on

reducing exposure to predictable high risk situations.

Be able to

provide additional appropriate information on patient support

groups and/or other sources

Have access to

a state registered dietitian competent in dealing with children

with food anaphylaxis

Be able to

recognise the potential effect of food allergen avoidance on

v15

Ref

Pathway stage

5j

Communication

5k

Immunotherapy

6

Emergency management

package for patients, their

families and other carers

[44;57;59;62-64]

7

Schools and Early Years

Settings (SEYS) care

8

Follow up

Page 13

Competence

growth and nutrition

supplement trigger avoidance advice and recommend suitable

alternatives to avoided foods

Be able to

communicate with patients, parents and carers, primary care,

other health care professionals, schools and early years settings

(SEYS) and where necessary social services

Know

how to share appropriate information to support other health

care professionals in performing a risk assessment

Have access to

a specialist unit, with full paediatric resuscitation facilities

the appropriate expertise and experience in performing

immunotherapy

Know

the indications and contraindications for immunotherapy

when to cease immunotherapy

Be able to

select patients appropriately for immunotherapy

Be able to provide an emergency management package that

includes:

a written or electronic emergency treatment plan for future

anaphylactic reactions that includes [57;63]

– contact details [63]

– allergen avoidance advice [44]

– advice on recognising symptoms [63]

– guidance when to use each medication during a reaction [35]

– age, language and psychosocially appropriate information

sources

appropriate emergency medication [26] based on risk

assessment (refer to box 11).

training in the use of emergency medication [35]

provision to review the management plan

repetition of training

Have

adequate liaison with SEYS

Be able to:

advise SEYS on the provision of rescue treatment

train SEYS personnel [65]

– in recognition of anaphylaxis

– on avoidance of identified trigger(s)

– to be able to use emergency medication when appropriate

repeat training annually

Have

facilities and expertise to be able to provide adequate follow up

Know

the natural history of allergy in childhood

Be able to

diagnose new allergies

modify allergen avoidance advice according to new information

adjust the dose of adrenaline injectors according to change in

body weight

update dietetic advice

access trained personnel to update school training as required

detect possible resolution by repeating investigations including

v15

Ref

Pathway stage

Page 14

Competence

allergen challenges if required

update emergency management plan

assess asthma control and adjust therapy as required

inform children and families about the process and appropriate

timing for obtaining a medical identity bracelet

v15

Conflict of interest

Table 3: Conflict of Interest

Name

Representation

Position

Conflict

Dr Andrew Clark

Tertiary Care - Paediatric

Allergist

Paediatric Allergist,

Addenbrookes Hospital

Consultancy: Schering Plough. Member: BSACI

council, BSACI Standards of Care Committee

Dr Mazin Alfaham

Secondary Care Paediatrician

Paediatric Consultant,

University Hospital of Wales

NIL

Dr Pamela Ewan

Secondary Care - Adult

Allergist

Mrs Louise Sinnott

Commissioning/DoH

Allergy Pilot

Adult Allergist, Addenbrookes

Hospital

NW Allergy and Clinical

Immunology Project Manager,

NHS North West Specialised

Commissioning Team

NIL

Dr Ian Maconochie

Emergency

ED Paediatrician, St Mary's

Hospital

Member: Resuscitation Council, UK (RCUK)

Dr Fiona Jewkes

JRCALC

Ms Rosie King

Nursing

Hon Secretary and RCPCH

representative, JRCALC

Allergy Nurse Specialist,

Southampton University

Hospital NHS Trust

TBC

Representative: RCGP/JRCALC on RCUK

Anaphylaxis Guidelines

Member: RCUK Executive

Member: BSACI

Employed by Anaphylaxis UK. Work with the

National Allergy Strategy Group

Member: BSACI

Ms Mandy East

Patient/Parent/Carer

Mr Stephen Tomlin

Pharmacist

Parent Rep, Anaphylaxis

Campaign

Consultant Pharmacist Children's Services, Evelina

Children's Hospital

Prof Aziz Sheikh

Primary Care / RCGP

Professor of Primary Care

Research and Development,

University of Edinburgh

Family members with anaphylaxis. Ongoing

programme of work funded by the Government

and charitable donors in relation to allergic

disorders which include anaphylaxis.

Ms Kate Lloydhope

Project Manager

Project Manager, RCPCH

NIL

Dr Dalbir Sohi

Secondary Care

General Paediatrician, Royal

Free Hampstead NHS Trust

NIL

Dr Susan Leech

Tertiary Care - Paediatric

Allergist

Paediatric Allergist, Kings

College Hospital

Member: BSACI

Paediatric Allergist, St Mary's

Hospital

Lectures/Consultancy: Novartis, Danone,

Airsonelte, Merck, Allergy Therapeutics. Trustee:

Anaphylaxis Campaign (until Jul 2009). Member:

steering committee for BTS/SIGN asthma

guideline. Research Funding/Support: GSK,

AstraZeneca, Merck, Danone, Airsonelte, Allergy

Therapeutics, ALK

Prof John Warner

Page 15

Tertiary Care - Paediatric

Allergist

NIL

v15

References

20

Pearson S, Goulart-Fisher D, Lee T. Critical Pathways as a Strategy for Improving Care: Problems and

Potential. Ann Intern Med 1998; 123:-941.

21

Bandolier. What is an integrated care pathway? Bandolier Journal 2001; 3(3):1-8.

22

Johansson SGO, Bieber T, Dahl R, Friedmann PS, Lanier BQ, Lockey RF et al. Revised nomenclature

for allergy for global use: report of the Nomenclature review Committee of the World Allergy

Organization, October 2003. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113:832-836.

23

Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF, Bock SA, Branum A et al. Second

symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: Summary report-Second National Institute of

Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2006; 117(2):391-397.

Page 16

24

Chinn D, Sheik A. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis. In: Pawankar R, Holgate S, Rosenwasser L, editors.

Allergy frontiers: Epigenetics, allergens and risk factors. Tokyo: Springer, 2009: 123-144.

25

Bock S, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sampson H. Fatalaties due to anaphylactic reactions to foods. J Allergy

Clin Immunol 2001; 107:191-193.

26

Simons FE. Anaphylaxis, killer allergy: Long-term management in the community. J Allergy Clin Immunol

2006; 117(2):367-377.

27

Simons FE, Frew AJ, Ansotegui IJ, Bochner BS, Golden DB, Finkelman FD et al. Risk assessment in

anaphylaxis: current and future approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120(1):S2-S24.

28

Simons FE. Anaphylaxis in infants: can recognition and management be improved? Journal of

Allergy & Clinical Immunology 2007; 120(3):537-540.

29

Simons F. Epinephrine autoinjectors: first-aid treatment still out of reach for many at risk in the

community. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2009; 102(403):409.

30

Sheik A, Alves B. Age, sex geographical and socio-economic variations in admissions for

anaphylaxis: analysis of four years of English hospital data. Clin Exp Allergy 2001; 31(10):1571-1576.

31

Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan D, Anderson H. Increasing hospital admissions for systematic allergic

disorders in England: analysis of national admissions data. BMJ 2004; 327:1142-1143.

32

Sheikh A, Alves B. Hospital admissions for acute anaphylaxis: time trend study. BMJ 2000; 320:1441.

33

Alves B, Sheikh A. Age specific aetiology of anaphylaxis. Arch Dis Child 2001; 85(4):348.

34

Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan D, Anderson H. Time trends in allergic disorders in the UK. Thorax 2007;

62:91-96.

35

Sheikh A, Hippisley-Cox J, Netwon J, Fenty J. Trends in national incidence, lifetime prevalence, and

adrenaline prescribing for Anaphylaxis in England. J R Soc Med 2008; 101:139-143.

36

Simons FE, Sampson HA. Anaphylaxis epidemic: fact or fiction? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;

122:1166-1168.

37

Braganza S, Acworth J, Mckinnon D, Peake J, Brown A. Paediatric emergency department

anaphylaxis: different patterns from adults. Arch Dis Child 2006; 91:159-163.

38

Novembre E, Cianferoni A, Bernardini R, Mugnaini L, Caffarelli C, Cavagni G et al. Anaphylaxis in

Children: Clinical and Allergologic Features. Pediatrics 1998; 101(4):e8.

39

Mehl A, Wahn U, Niggemann B. Anaphylactic reactions in children – a questionnaire-based survey in

Germany. Allergy 2005; 60:1440-1445.

40

Lieberman P, Camargo CJr, Bohlke K, Jick H, Miller R, Sheikh A et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis:

findings of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Epidemiology of Anaphylaxis

Working Group. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006; 97:596-602.

41

Webb LM, Lieberman P. Anaphylaxis: a review of 601 cases. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, &

Immunology 2006; 97(1):39-43.

42

Gaeta J, Clark S, Pelletier A, Camargo C. National study of US emergency department visits for acute

allergic reactions, 1993 to 2004. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2007; 98:360-365.

43

Pumphrey RS. Anaphylaxis: can we tell who is at risk of a fatal reaction? Curr Opin Allergy Clin

Immunol 2004; 4:285-290.

44

Kemp AS, Hu W. New action plans for the management of anaphylaxis. Australian Family Physician

2009; 38(1/2):31.

Page 17

45

Sheikh A, Shehata YA, Brown SGA, Simons FE. Adrenaline (epinephrine) for the treatment of

anaphylaxis. Cochrane 2008; 4.

46

Department of Health. A review of services for allergy - the epidemiology, demand for and provision

of treatment and effectiveness of clinical interventions. DH Allergy Services Review Team, editor.

2006. London, Department of Health.

47

Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy

2000;30, 8: 1144-1150.

48

CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Program [Online]. [accessed: 26/09/2009] Available from: http://www

phru nhs uk/Pages/PHD/CASP htm 2009. CASP, Public Health Resource Unit, Oxford.

49

SIGN. Annex B: Key to evidence statements and grades of recommendations [Online]. [accessed:

26/09/2009] http://www sign ac uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/annexb html 2009. CASP, Public Health

Resource Unit, Oxford.

50

AGREE Collaboration. AGREE Instrument. [accessed: 26/09/09] Available from: http://www

agreecollaboration org/instrument/ 2001.

51

Resucitation Council (UK). The emergency medical treatment of anaphylactic reactions. Guidelines

for healthcare providers. 2008; 1-50. London, Resucitation Council (UK).

52

RCP. A new series of evidence-based guidelines for clinical management. In: Turner-Stokes L, editor.

Concise Guidance to Good Practice. London: RCP, 2003: 1-12.

53

RCPCH. A Framework of Competences for Level 3 Training in Paediatric Immunology, Infectious

Diseases and Allergy [Online]. [accessed: 05/10/2009] http://www rcpch ac uk/doc

aspx?id_Resource=4355 2008.

54

RCPCH. A Framework of Competences for training general paediatricians with an interest in allergy.

Forthcoming. 2010.

55

Skills for Health. Competence Application Tools [Online]. [accessed: 05/10/2009] https://tools

skillsforhealth org

uk/competence/searchResults?keywords=allergy&level%5B%5D=1&level%5B%5D=2&level%5B%5D=

3&level%5B%5D=4&adv_search x=4&adv_search y=8 2009.

56

Department of Health. National service framework for children, young people and maternity services

[Online]. [accessed: 12/11/09] http://www dh gov

uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4089100 2004.

Department of Health.

57

Clark AT, Ewan PW. Good prognosis, clinical features, and circumstances of peanut and tree nut

reactions in children treated by a specialist allergy centre. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122(2):286289.

58

de Silva I, Mehr S, Tey D, Tang M. Paediatric anaphylaxis: a 5 year retrospective review. Allergy 2008;

63(8):1071-1076.

59

Mirakian R, Ewan PW, Durham SR, Youlten LJ, Dugue P, Friedmann PS et al. BSACI guidelines for the

management of drug allergy. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2009; 39(1):43-61.

60

Singh J, Aszkenasy OM. Prescription of adrenaline auto-injectors for potential anaphylaxis--a

population survey. Public Health 2003; 117(4):256-259.

61

Kapoor S, Roberts G, Bynoe Y, Gaughan M, Habibi P, Lack G. Influence of a multidisciplinary

paediatric allergy clinic on parental knowledge and rate of subsequent allergic reactions. Allergy

2004; 59(2):185-191.

62

Muraro A, Roberts G, Clark A, Eigenmann PA, Halken S, Lack G et al. The management of

anaphylaxis in childhood: position paper of the European academy of allergology and clinical

immunology. Allergy 2007; 62(8):857-871.

Page 18

63

Nurmatov U, Worth A, Sheikh A. Anaphylaxis management plans for the acute and long-term

management of anaphylaxis: A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122(2):353-361.

64

Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clinical &

Experimental Allergy 2000; 30(8):1144-1150.

65

Anaphylaxis Campaign. Be AllergyWise - Training for school nurses [Online]. [accessed: 05/10/2009]

http://www anaphylaxis org uk/allergywise aspx 2008. Anaphylaxis Campaign.

Page 19

Appendix 1: Glossary

Acronym

AWG

CAHMS

CAM

CASP

ED

ENT

NICE

NSF

PICOS

RCP

RCPCH

RCUK

SEYS

SIGN

Page 20

Means

Anaphylaxis Working Group

Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Critical Skills Appraisal Program

Emergency Department

Ear, Nose and Throat

National Institute of Clinical Excellence

National Service Framework

Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Studies

Royal College of Physicians

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health

Resuscitation Council, United Kingdom

Schools and Early Years Settings

Scottish Intercollegiate Network

Appendix 2: Evidence Table: systematic reviews and primary research

Table 4: Evidence table: systematic reviews and primary research

Bibliographic Reference

Choo, K. and A. Sheikh.

"Action plans for the long-term

management of anaphylaxis:

systematic review of

effectiveness." Clinical and

Experimental Allergy 37.7

(2007): 1090-94

Sheik A, ten Broek WM, Brown

SGA, Simons FE. “H1antihistamines for the

treatment of anaphylaxis with

and without shock.” Cochrane

Database of Systematic

Reviews 2007; 1.

Sheikh A et al. "Adrenaline

(epinephrine) for the treatment

of anaphylaxis." Cochrane 4

(2008)

Ewan P, Clark AT. “Efficacy of

a management plan based on

severity assessment in

longitudinal and case

controlled studies of 747

children with nut allergy:

proposal for good practice.”

Clin Exp Allergy 2005; 35:751756.

Page 21

Study

Systematic

Review

Systematic

Review – Part A

Systematic

Review – Part A

Nested casecontrol (N=112

cases, 112

controls) in

longitudinal

prospective cohort

study of children

with confirmed

peanut or treenut

allergy (N=615)

Quality Assessment

Systematic search for RCT's and

quasi-RCTs conducted in CENTRAL,

Cochrane, Medline and Embase. Mixed

child and adult study. This study

identified no RCTor quasi-RCT

evidence to guide clinical practice.

Systematic search for RCT's and quasiRCTs in CENTRAL, MEdline, CINHAL,

ISI web of science and grey literature

and pre-publication with clear inclusion

and exclusion criteria. Found no RCT

evidence. Evidence presented in the

discussion section of the systematic

review has no clear inclusion and

exclusion criteria .

Systematic search for RCT's and quasiRCTs conducted in CENTRAL,

Cochrane, Medline and Embase. Found

no RCT evidence. However, the

discussion evidence has no clear

inclusion and exclusion criteria listed.

Caseswere well defined (confirmed

diagnosis) and controls were matched

according to sex, age at onset, age at

enrolment and duration of follow up. No

power calculation is reported for the

sample size

Key outcomes

Although there are potential major benefits of routinely issuing anaphylaxis

action plans, there is currently no robust evidence to guide clinical practice.

Pragmatic randomized-controlled trials of anaphylaxis action plans are

urgently needed; in the meantime, national and international guidelines should

make clear this major gap

No high level evidence for or against the use of H1 antihistamines in

anaphylaxis, this may be due to: 1. anaphylaxis is a potentially life threatening

emergency situation. 2. Absence of a universally accepted definition on this

topic.

This review failed to uncover any evidence from prospective, randomized or

quasi-randomized trials on the effectiveness of adrenaline for the emergency

management of anaphylaxis. Conducting research in this area is challenging

due to : 1. The established position of adrenaline treatment making it difficult

to argue for placebo controlled trials, 2. the ethics of obtaining informed

consent in emergency situations, 3. the difficulty in conducted double blind

placebo controlled trials due to the transient nature of adrenaline treatment, 4.

the fact that anaphylaxis usually occurs without warning in non medical

settings, the difficulty in obtaining baseline measurements.

There was an eight fold reduction in reaction frequency after enrolment in the

management plan and a 60 fold reduction in the frequency of severe

reactions. Of mild-moderate reactions 77% required oral antihistamines alone

and 15% no treatment. Children who had follow up reactions had more

frequent and severe reactions pre follow up and were older (median age 13

years). Considerations for criteria for provision of injectable adrenaline were

difficult to devise. Children with mild reactions were not prescribed injectable

adrenaline unless there was ongoing asthma or only traces had ever been

ingested. All patients were asked to carry antihistamines. This study also

provides reassurance about the safety of intramuscular adrenaline.

Level

1+

1+

1+

2++

Bibliographic Reference

Murphy KR, Hopp RJ,

Kittelson EB, Windle ML. “Life

threatening asthma and

anaphylaxis in schools: a

treatment model for school

based programs.” Ann Allergy

Asthma Immunology 2006;

96:398-405.

Prospective

Cohort (78

schools serving

45,000 children,

N=98 children

successfully

treated)

Studying the implementation of a

protocol in schools. Trained staff

collected the data. No statistical

analysis is performed.

Rancé F, Abbal M, LauwersCancès V. “Improved

screening for peanut allergy by

the combined use of skin prick

tests and specific IgE assays.”

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;

109(6):1027-1033.

Diagnostic Test:

cross sectional

study of children

with suspected

food

hypersensitivity

(N=363)

Appropriate design with use of negative

and positive controls. Sensitivity and

specificity with confidence intervals

reported.

Page 22

Study

Quality Assessment

Key outcomes

Selected school staff were fully trained. This protocol resulted in students and

staff having more knowledge of severe allergies. For students to return to

school they must have anaphylaxis action plan (AAP) and medication (or a

waiver). Parents expressed a feeling of safety generated by the knowledge

that a rapid response network exists. The protocol has led to early

intervention for severe asthma attacks, anaphylactic events and allergic

reactions. Rapid access to emergency medical care, patient educations and

caregiver education are the key components to make this program successful.

1.The DBPCFC is the gold standard for diagnosing peanut allergy because it

has a sensitivity and a specificity of 100%. 2.In our study the combined use of

the 2 tests made it quite certain that children had peanut allergy when one of

the 2 test results was positive (≥16 mm for the raw SPT and ≥57 kUA/L for the

specific IgE assay) with a sensitivity of 27.7% and a specificity of 100%. 3.A

skin reaction diameter of less than 3 mm combined with a specific IgE assay

result of less than 57 kUA/L totally eliminated the possibility of peanut allergy

(100% NPV). 4.For other raw SPT and specific IgE assay values, there were

always false-positive and false-negative results that made it necessary to

perform an oral food challenge. 5. The clinical history must be taken into

consideration, and a DBPCFC should be undertaken when the history is

suspicious for a reaction. Our study corresponds to the first diagnostic step for

children with suspected food allergies. We did not observe children with

unequivocal histories of anaphylactic shock induced by ingestion of peanut.

This proposed diagnostic strategy must be confirmed in another population

with peanut allergy. 6. In the event of an unequivocal clinical history of

anaphylactic shock triggered by the ingestion of peanut, peanut consumption

must be forbidden, no matter what the values of the SPT and specific IgE

assay. However, when in doubt, a DBPCFC must be performed. A strong

suspicion of peanut allergy despite negative test results should lead to a

DBPCFC under medical supervision and not a return home with no specific

dietary advice. Superior effectiveness of raw extracts over commercial

extracts

Level

2+

2+

Bibliographic Reference

Sporik R, Hill DJ, Hosking CS.

“Specificity of allergen skin

testing in predicting positive

open food challenges to milk,

egg and peanut in children.”

Clin Exp Allergy 2000;

30:1540-1546.

Braganza, SC et al. "Paediatric

emergency department

anaphylaxis: different patterns

from adults." Arch Dis Child 91

(2006): 159-63

Clark AT and Ewan PW.

"Good prognosis, clinical

features, and circumstances of

peanut and tree nut reactions

in children treated by a

specialist allergy centre." J

Allergy Clin Immunol 122.2

(2008): 286-89

de Silva, IL et al. "Paediatric

anaphylaxis: a 5 year

retrospective review." Allergy

63.8 (2008): 1071-76

Page 23

Study

Diagnostic Test:

Prospective

cohort of children

referred to a

tertiary allergy

clinic with

suspected food

allergy (N=467,

with 555 food

challenges)

Retrospective

case series of

children under 16

(N=526,

generalised

allergic reaction,

N=57

anaphylaxis)

Prospective case

series of children

with peanut/nut

allergy (N=785)

Retrospective

case series of

children with

anaphylaxis

(N=117)

Quality Assessment

Positive and negative controls. No

blinding due to the life threatening

nature of anaphylaxis. Sensitivity,

specificity and likelihood ratios reported

with confidence intervals

Key outcomes

SPT cut-off levels will be different according to the clinical context, the allergen

extract used and the age of the child. Positive food challenges were always

seen when the skin weal diameter was greater than a certain size: cow milk, 8

mm; egg, 7 mm; and peanut, 8mm. In children aged less than 2 years these

diameters were correspondingly smaller: cow milk, 6 mm; egg, 5 mm; and

peanut, 4 mm. This implies that weal diameters equal to or greater than these

diameters were 100% specific in defining the outcome of food challenges.

The findings from this prospective study have changed the food challenge

policy of this unit. If a child has on initial evaluation a skin test weal to cow

milk, egg, or peanut exceeding the above defined limits the child is considered

allergic to that food and does not undergo further evaluation.

Those with a lesser skin reactivity are challenged. Children are restudied

annually and challenged according to the skin test results. All children with

adverse reactions to other foods (such as soy and wheat) were the predictive

value of skin testing has not been defined, and in our experience is not as

clear, also require food challenges. However, caution needs to be applied in

extrapolating our results with these allergen extracts to other populations, of

different ages, where different skin test reagents of varying potency, and

different methodologies may be used.

Retrospective case study is a weak

design. No validation of data entry or

cross checking for accuracy of data

inputting.

The annual incidence of paediatric emergency department generalised allergic

reactions was found to be 9.3:1000 presentations, and that of anaphylaxis

was 1:1000 presentations, with prevalence figures of 2.47:1000 and 0.27:1000

paediatric population respectively.

The commonest cause of paediatric emergency department anaphylaxis was

found to be food items, followed by drugs and then insect venom, with

respiratory clinical features predominating

Prospective case series design, which

is a weak study design to guide decision

making. Source of participants was

clinic population, this may introduce

bias.

Retrospective case study is a weak

design. Disease was clearly defined

and information was gathered from

hospital coded notes. Patient exclusion

was clear and strict.

With a comprehensive management plan (detailed written and verbal age

appropriate advice on nut avoidance, provision of emergency medication ,

training of family members in the use of emergency medication, notification of

each child’s school or nursery), accidental reactions were uncommon and

usually mild, most requiring little treatment; 99.8% self-treated appropriately

and 100% effectively. Favourable prognosis for children attending a specialist

allergy clinic with an annual incidence rate for accidental ingestion of peanut

and/or tree nuts after diagnosis of 3%. This rate is substantially lower than

rates in other studies of accidental exposure to peanut alone e.g. 14-55% in

previous studies

1. Most cases presenting with anaphylaxis were experiencing their first

reaction; 2. Most cases were triggered by food consumed at home; 3.

Reactions developed quickly; 4. Although many children received treatment

with adrenaline, treatment was often delayed and given through a sub-optimal

route; 5. Case fatality rate was low.

Level

2+

3

3

3

Bibliographic Reference

du, Toit G. "Food-dependent

exercise-induced anaphylaxis

in childhood." Pediatric Allergy

& Immunology 18.5 (2007):

455-63

Study

Educational series

(case reports)

(N=3)

Quality Assessment

The author presented 3 case reports of

a rare condition. To gain a thorough

evidence based perspective a single

site study, as in this case, is suboptimal.

Gold and Sainsbury. "First aid

anaphylaxis management." J

Allergy Clin Immunol 106.1

(2000): 171-76

Retrospective

telephone survey

of parents of

children with a

history of

anaphylaxis

(n=68)

Case series design, which is a weak

study design. Small number of

participants

Hu W, Grbich C, Kemp A.

“Parental food allergy

information needs: a

qualitative study.” Arch Dis

Child 2007; 92:771-775.

Semi structured

interviews of

parents of

children with food

allergy (48

families, N=84)

Semi structured interviews are a good

way to obtain information needs.

Selection well explained, potential bias

noted, no reasons for declining noted

though.

Page 24

Key outcomes

The diagnosis of food dependant exercise induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA) is

heavily dependent on the clinical history. Allergy tests may need to be

performed to a broad panel of food and food additives. Modified exercise

challenges (performed with and without prior ingestion of food) are frequently

required as allergy test results frequently return low-positive results. A

diagnosis of FDEIA facilitates the safe independent return to exercise and

reintroduction of foods for patients who otherwise may unnecessarily avoid

exercise and/or restrict their diet. The natural history of FDEIA is unknown;

however, a safe return is usually achieved when the ingestion of the causal

food allergen/s and exercise are separated.

Recurrent generalized allergic reactions occurred with a frequency of 0.98

episodes per patient per year and were more common in those with food

compared with insect venom anaphylaxis.

The adrenaline injector device was only used in 29% of recurrent anaphylactic

reactions. Parental knowledge was deficient in recognition of the symptoms of

anaphylaxis and use of the adrenaline injector device, and adequate first aid

measures were not in place for the majority of children attending school.

Those children in whom the adrenaline injector device was used were less

likely to be given epinephrine in hospital and to require subsequent hospital

admission.

The adrenaline injector device is infrequently used in children with recurrent

episodes of anaphylaxis; the reasons for this require further research. It is

likely that parents and other caregivers will require continuing education and

support in first aid anaphylaxis management. When the adrenaline injector

device is used appropriately, it appears to reduce subsequent morbidity from

anaphylaxis.

3 information phases: initial diagnosis, follow-up and milestone. Content

needs: 1. reasoning behind the doctor’s judgments about their child’s allergy,

including the likelihood of anaphylaxis, and the recommended management.

2. basic medical facts and practical advice related to daily management. l

What is anaphylaxis? What is not anaphylaxis? // l Recognising symptoms of

allergic reactions, the timescale of reactions. // l How accidental exposures

occur and how to manage risky situations. // l What to feed your child (rather

than what to avoid), maintenance of nutrition. // l Practical allergen avoidance:

label reading, shopping, cooking, social events, eating out and travel. How to

find allergen-free products. // l When and how to give the adrenaline injector.

Revision of techniques at each visit. // l How to educate extended family, other

carers and adults who may give the child food. // l Risks and benefits of skin

testing and oral challenges. Interpretation of results. // l When follow-up is

required, and why. // l Where more information may be found, e.g. nurse-led

education sessions, consumer organisations, contacting the clinic. // l How to

educate your child. // l Background information about allergy, the relationship

Level

3

3

3

Bibliographic Reference

Study

Quality Assessment

Key outcomes

between asthma, eczema and food allergy, natural history of food allergy.

information delivery: 1. clinic procedures and accessibility (multiple events,

overwhelming, bored child), 2. formats. Written take-home information was

strongly preferred, as it was difficult to recall details about food ingredients and

products, but not as a substitute for talking with a health professional. Parents

also spoke highly of videos. 3. third and most important aspect was the

doctor–parent–child relationship. The most common reasons for seeking a

second opinion were insufficient information provision

Kapoor S et al. "Influence of a

multidisciplinary paediatric

allergy clinic on parental

knowledge and rate of

subsequent allergic reactions."

Allergy 59.2 (2004): 185-91

Case series

(N=52) with

survey parent’s of

children with food

allergy

No comparator group - allergy

management plan was given to all

participants

Pumphrey, R. S. "Lessons for

management of anaphylaxis

from a study of fatal reactions."

Clinical & Experimental Allergy

30.8 (2000): 1144-50

Retrospective

case review of

164 allergic

fatalities of adults

and children

(1992-1998)

Weak study design (case series).

Subjects referred with food allergy were prospectively enrolled in this study.

Parental knowledge was reassessed after 3 months and rate of allergic

reactions after 1 year. The study found benefits of accessing a paediatric

allergy clinic. After one visit to the paediatric allergy clinic, there was a

significant improvement in parental knowledge of allergen avoidance (26.9%,

P < 0.001), managing allergic reactions (185.4%, P < 0.0001) and adrenaline

injector usage (83.3%, P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant

reduction in allergic reactions (P < 0.001).

Immediate recognition of anaphylaxis, early use of adrenaline, inhaled beta

agonists and other measures are crucial for successful treatment. Optimal

management of anaphylaxis is therefore avoidance of the cause whenever

this is possible. Predictable cross-reactivity between the cause of the fatal

reaction and that of previous reactions had been overlooked. Adrenaline

overdose caused at least three deaths and must be avoided. Kit for selftreatment had proved unhelpful for a variety of reasons; its success depends

on selection of appropriate medication, ease of use and good training.

Because all food related reactions caused difficulty breathing paramedics had

difficulty in deciding whether to use the protocol for asthma or anaphylaxis

A case series is a weak design. No

confidence intervals around calculated

parameters were reported.

Children with allergies should be treated in an allergy clinic. Also showing

effect of allergy on quality of life. Set out to assess the quality of training that is

provided for parents with children who were given adrenaline auto-injector,

adherence to recommendations regarding where these children should be

treated, and effect of allergy on quality of life. Training provided was very

poor. Almost 50% were not assessed in allergy clinic. 14.9% of children were

bullied as a result of their allergy. 28% of parents felt that their child could not

do something they really enjoyed as a result of the allergy, and 36.4% of

parents felt that their own lifestyle was affected.

Singh, J. and O. M.

Aszkenasy. "Prescription of

adrenaline auto-injectors for

potential anaphylaxis--a

population survey." Public

Health 117.4 (2003): 256-59

Page 25

Cross sectional

case series postal

survey of parents

of children

prescribed with

adrenaline injector

(N=154)

Level

3

3

3

Bibliographic Reference

Kemp, A. S and W. Hu. "New

action plans for the

management of anaphylaxis."

Australian Family Physician

38.1/2 (2009): 31

Nurmatov U, Worth A, and

Sheikh A. "Anaphylaxis

management plans for the

acute and long-term

management of anaphylaxis: A

systematic review." J Allergy

Clin Immunol 122.2 (2008):

353-61

Study

Quality Assessment

Comment

No methodology for the development of

the anaphylaxis management plans is

outlined.

Systematic

Review

Systematic search for conducted in

Medline, Embase, Science Citation

Index, Cochrane, , ISI proceedings,

TRIP, LILACS and CINAHL. No RCT

evidence and limited consensus on

what should be included in

management plans.

Sheik A, ten Broek WM, Brown

SGA, Simons FE. “H1antihistamines for the

treatment of anaphylaxis with

and without shock.” Cochrane

Database of Systematic

Reviews 2007; 1.

Systematic

Review – Part B

see part A

Sheikh A et al. "Adrenaline

(epinephrine) for the treatment

of anaphylaxis." Cochrane 4

(2008)

Systematic

Review – Part B

see part A

Page 26

Key outcomes

Standardised action plan templates are likely to reduce confusion caused by

varying instructions and differing plans formulated by medical practitioners or

by parents and carers. All action plans should:

• list allergens that need to be avoided

• provide instructions for action in the setting of an allergic reaction and/or

anaphylaxis

• be dated and signed by a medical practitioner, and

• be easily accessible by carers.

It is essential that patients provided with action plans be regularly reviewed.

Commonly this is done annually, but may vary depending upon

circumstances.

Anaphylaxis Management Plans should have emergency contact details,

advice on recognition of symptoms and treatment of reactions with

epinephrine. Written plans appear to be acceptable to patients and caregivers

and might when issued together with training reduce anxiety levels and

increase knowledge and self-efficacy among parents and school staff

Implications for practice: We found no relevant evidence. We are therefore

unable to make recommendations about H1-antihistamine use in the treatment

of anaphylaxis. Guidelines on the management of anaphylaxis need to be

much more explicit about the basis of their recommendations regarding the

use of H1-antihistamines. Implications for research: there is a case for RCTs

of high methodological rigour to define the true benefit from H1-antihistamines

in anaphylaxis. Specifically, more information is required on patients most

likely to benefit and the most appropriate preparations, route and dose of

administration. Any future trials would need to consider in particular: •

appropriate sample sizes with power to detect expected differences • careful

definition and selection of target patients • appropriate comparator therapy •

appropriate outcome measures including all those listed in this review • careful

elucidation of any adverse effects and the cost-utility of the therapy.

Intramuscular route for adrenaline is preferred.

Some disagreement exists about the recommended dose of adrenaline but

almost all of the literature agrees on 0.01 mg/kg in infants and children.

Delayed injection of adrenaline in anaphylaxis is reported to be associated

with mortality

Given that current evidence supports the relative safety of intramuscular

adrenaline, and early administration is believed to be associated with an

improved survival, any patient with a serious allergic reaction that is rapid in

onset should be a candidate for adrenaline by auto-injector.

Adrenaline has been associated with the induction of fatal cardiac arrhythmias

and myocardial infarction.

Level

4

4

4

4

Appendix 3: Evidence Table: Guidelines

Table 5: Evidence table: guidelines

Bibliographic Reference

Quality Assessment

RCPCH decision: Practice statement

A literature search of Medline, Scopus,

Cochrane, Embase, GoogleScholar was