30 YEARS OF BREATHING:

advertisement

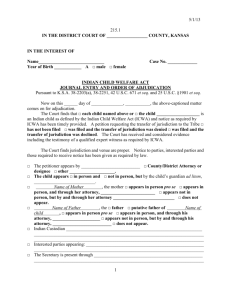

30 YEARS OF BREATHING: EMERGING ISSUES UNDER THE INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT OF 1978 _________________ JILL ELIZABETH TOMPKINS Clinical Professor of Law Director, American Indian Law Clinic University of Colorado Law School 404 UCB Boulder, Colorado 80309-0404 (303) 735-2194 Email: jill.tompkins@colorado.edu 30 YEARS OF BREATHING: EMERGING ISSUES UNDER THE INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT OF 1978 JILL ELIZABETH TOMPKINS1 “Breathe” -- 1) to draw in and let out (air etc.) from the lungs; 2) to be exposed to air after being uncorked, in order to develop flavor and bouquet (of a wine). 2 I. INTRODUCTION Three decades have passed since the United States Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act of 19783 (“ICWA”) in an effort to “protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes by the establishment of minimum federal standards for the removal of Indian children from their families and the placement of such children in foster and adoptive homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture . . . .”4 In those 30 years, ICWA has largely achieved the aspirational goals articulated by Congress. Despite the fact that the United States Supreme Court has only rendered one opinion, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield,5 more than 19 years ago, ICWA continues to “breathe” – to be embraced by many of states which Congress set out to rein in and to be * Prepared for the 33rd Annual Federal Bar Association Indian Law Conference. Clinical Professor of Law, Director, American Indian Law Clinic, University of Colorado Law School; Appellate Justice, Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians Court of Appeals, Mashantucket Pequot Court of Appeals and Passamaquoddy Tribal Appellate Court, J.D., University of Maine School of Law. The author is a member of the Penobscot (Burnurwurbskek) Indian Nation. I thank Melissa Pingley, ’08 for her valuable research assistance. I also want to express my gratitude to the Native American Rights Fund and the National Indian Law Library for their invaluable publication A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO THE INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT found at their comprehensive website: http://narf.org/icwa. 2 “Breathe” at www.dictionary.com, http://dictionary.reference.com /browse/breathe (last visited 02/19/08). 3 25 U.S.C. § 1901 et seq. 4 25 U.S.C. § 1902. 5 490 U.S. 30 (1989). 1 resisted by others. With the urbanization of Native America and the strains placed on state social services agencies, new challenges are arising requiring ICWA to be applied in recently authorized private non-parent custody actions. This article explores how ICWA, after 30 years of life, continues to breathe--to be expanded and enhanced by states and their courts in some respects, and, to be contracted and thwarted in others. It will also alert family law practitioners and domestic relations judges to an emerging area, non-parent private custody actions involving Indian children, where ICWA may be applicable. II. BREATHING IN: STATES ENACT ICWA IMPLEMENTING LEGISLATION The provisions of ICWA apply to foster care proceedings, pre-adoptive placements and adoptive placements of Indian children occurring in state courts.6 State judges and court officers involved in the day to day adjudication and disposition of such cases are accustomed to applying state law and procedures exclusively. Thus it is easy to overlook the possible applicability of a federal statute, namely ICWA, when it may rarely arise in the state juvenile or family court context. One of the most positive developments in recent years is the enactment of amendments to state children’s codes to include specific mention of the possible applicability of ICWA to state court proceedings concerning the custody of Indian children. As of this date, at least 14 states have included mention of ICWA in their state laws governing children’s cases.7 Many more include general references in the state children’s statutes 6 See 25 U.S.C. § 1903(1). California, Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Washington, Wisconsin and Wyoming. http://narf.org/icwa/state. 7 2 indicating that ICWA may apply.8 The States of California and New Mexico have included the most frequent ICWA references through their statutes.9 Among the 14 states with specific ICWA-implementation legislation, the most often-appearing provisions concern the required notice of child custody proceedings to an Indian child’s parents or Indian custodian and to the Indian child’s tribe mandated by 25 U.S.C. § 1912(a).10 The federal regulations add a lengthy detailed list of information regarding the child and the proceeding that should be included in the notice as well as appropriate attachments, such as a copy of the petition.11 The Bureau of Indian Affairs Guidelines for State Courts; Indian Child Custody Proceedings contains a similar ten point list of items to be included in the notice, which should be accompanied by a copy of the document initiating the proceeding.12 The Guidelines are not binding on state courts, but many have found them persuasive.13 The statutes of California, Iowa, Michigan, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Washington all include provisions substantially similar to the federal statutory, regulatory or guideline notice language. Some states take the additional step of adding language to further refine or enhance the notice provisions. California and Colorado, for example, direct that the tribal notice be sent to a particular 8 See OR. REV. STAT. § 419.B.878 (2001); WYO. STAT. § 14-3-412(b)(v)(2005). See collected at http://narf.org/icwa/state. 10 Section 1912(a) provides that, “In any involuntary proceeding in State court, where the court knows or has reason to know that an Indian child is involved, the party seeking foster care placement or termination of parental rights to, an Indian child shall notify the parent or Indian custodian and the Indian child’s tribe, by registered mail with return receipt requested, of the pending proceedings and of their right of intervention. If the identity or location of the parent or Indian custodian and the tribe cannot be determined, such notice shall be given to the Secretary in like manner, who shall have fifteen days after receipt to provide the requisite notice to the parent or Indian custodian and the tribe. No foster care placement or termination of parental rights proceeding shall be held until at least ten days after receipt of notice by the parent or Indian custodian and the tribe or the Secretary: Provided, That the parent or Indian custodian or the tribe shall, upon request, be granted up to twenty additional days to prepare for such proceeding. 25 U.S.C. § 1912(a)(emphasis supplied). 11 25 CFR 23.11(d),(e). 12 44 FED.REG. 67584 (Nov. 26, 1979) at B.5 “Notice Requirements.” 13 B.H. v. People ex rel. X.H.,138 P.3d 299, 301, n. 2 (Colo.2006). 9 3 person, for example the tribal chairperson, or office, such as tribal social services, instead of just to “the tribe” as required by ICWA itself.14 In her article, “Colorado Moves Toward Full Compliance with Federal Indian Child Welfare Act,” Brenda J. Bellonger explains that the separate additional notice to the tribe’s social services agency, “. . . is intended to enhance the effectiveness of the notice, inasmuch as the social services worker in the tribe is primarily responsible for processing the ICWA case through tribal procedures.”15 Section 1912(a) of ICWA requires that notices be sent by registered mail, return receipt requested. 16 Some states have added to their children’s codes the common-sense requirement that the receipts be filed with the court.17 A troubling trend, however, was apparent in a review of the states’ ICWA notice mailing requirements in that several states, California, Nebraska, New Mexico and Washington, have deviated from the federal statutory mandate of registered mail service, the most secure method of delivery offered by the United States Postal Service, and allow service by certified mail instead.18 At the time of the writing of this article, the State of Colorado is considering an 14 CAL. FAM. CODE § 180(B)(2) (2006)(“Notice to the tribe shall be to the tribal chairperson, unless the tribe has designated another agent for service.”); COLO. REV. STAT. § 19-1-126(b) (“If the petitioning or filing party knows or has reason to believe that the child who is the subject of the proceeding is an Indian, send notice . . . to the tribal agent of the Indian child’s tribe as designated in title 25 of the code of federal regulations . . . and to the social service department of the Indian child’s tribe.” 15 31 COLO.LAW. 77, 79 (Nov. 2002). 16 25 U.S.C. § 1912(a). 17 CAL. FAM. CODE § 180(b)(1) (2006); COLO. REV. STAT. § 19-1-126(c); MINN. STAT. § 260.761, Subd. 5 (“. . . [P]roof of service upon the child’s tribe or the secretary of interior must be filed with the adoption petition.”) 18 CAL. FAM. CODE § 180(b)(1) (2006) (registered or certified mail); NEB. REV. STAT. § 43-1505(1)(1987) (certified or registered mail); N.M. STAT. § 32A-4-29(C)(2005) (motion for termination of parental rights shall be sent by certified mail); WASH. REV. CODE §26.10.034(1)(a) (2004)(notice shall be by certified mail). 4 amendment to its Children’s Code to allow for mailing of ICWA notices by either registered or certified mail.19 In the area of federal Indian law, Congress has preempted the field with regard to Indian child custody actions and states may not regulate this area in a contrary fashion. A state may provide greater protections for Indian families, children and tribes, but may not enact provisions that attempt to lessen the protections of the federal law. In 1978, when ICWA was enacted, both the registered and certified mail processes existed. Congress chose registered mail. Congress alone has authority to change the requirement of Section 1912. While proponents of the Colorado notice bill argue that it could result in significant cost savings to Colorado county social service departments, what they are failing to consider is the jeopardy to Indian children that may result from the legal uncertainty surrounding future Indian child custody proceedings due to the failure to adhere to ICWA’s notice requirements. The financial resources that may have been saved by not using registered mail for sending notices may be consumed by subsequent lawsuits challenging the amendment. Other progressive ICWA-friendly state statutory provisions include the extension of coverage of ICWA to areas where they have been excluded or it has been unclear, such as juvenile delinquency matters20 and voluntary adoption proceedings.21 The State of Iowa took particular care to define the “active efforts” required by ICWA to “ . . . provide remedial services and rehabilitative programs designed to prevent the breakup of the Indian family . . . .” 22 “Reasonable efforts shall not be construed as active efforts. The active efforts must be made 19 H.B. 08-1206 (Colo. 2008) “A Bill for An Act Concerning Allowing Notice to be Served by Certified Mail in a Case Filed Under the Federal ‘Indian Child Welfare Act.’” 20 See COLO. REV. STAT. § 19-1-126(1)(2006); MI. R. SPEC. P. MCR 3.980(A)(1985). 21 N.M. STAT. § 32A-5-26 (2003). 22 25 U.S.C. § 1912(d). 5 in a manner that takes into account the prevailing social and cultural values, conditions and way of life of the Indian child’s tribe,” states the Iowa Child Welfare Act.23 The Iowa statute provides a detailed and lengthy list of efforts and services that may fulfill the requirement of active efforts.24 New Mexico included a thoughtful provision that the treatment plan for the Indian child is required to provide for the maintenance of the child’s cultural ties.25 For reasons discussed below, one of the most powerful provisions adopted by a state is that of the Iowa’s Indian Child Welfare Act which states, “A state court does not have discretion to determine the applicability of the federal Indian Child Welfare Act . . . based upon whether an Indian child is part of an existing Indian family.”26 This provision outlaws use of the “Existing Indian Family Exception” to avoid applying ICWA. Section 1911 of ICWA establishes the right of an Indian child’s parents or tribe to petition to transfer a state court proceeding for foster care placement or termination of parental rights to tribal court.27 The petition to transfer is to be granted absent: 1) a parent’s objection, 2) declination by the tribal court, or 3) “good cause” not to transfer.28 The term “good cause” is not defined by the Act, but the BIA Guidelines do provide some suggestions as to what may constitute good cause not to transfer, such as, the child’s tribe does not have a tribal court or the proceeding was at an advanced stage when the petition to transfer was filed.29 The states of Colorado, Iowa and Michigan all include provisions addressing petitions to 23 IA. ST. JUV. P. § 232B.5(19) (2003). Id. 25 N.M. STAT. § 32A-3B-19(F). 26 IA. ST. JUV. P. § 232B.5(2) (2003). 27 25 U.S.C. §1911(b). 28 Id. 29 44 FED. REG. at 67591, C.3 “Determination of Good Cause to the Contrary.” 24 6 transfer.30 Iowa’s Indian Child Welfare Act dictates that the court, “shall reject any objection that is inconsistent with the purposes of this chapter.”31 Michigan’s Rule 3.980, “American Indian Children” states that, “A perceived inadequacy of the tribal court or tribal services does not constitute good cause to refuse to transfer the case.”32 The inclusion of references to ICWA and enhancements to ICWA’s terms in state codes are important means of improving implementation of both the letter and spirit of ICWA. Moreover, state law provisions are able to be tailored to the circumstances of each state and the affected tribes and to address specific implementation problem areas.33 The trend of states adopting ICWA-related legislation is a highly effective way of promoting Congress’ responsibility for “protecting and preserv[ing] Indian tribes and their resources . . . [namely] their children.”34 The more “breathing in” of ICWA states do, through the enactment of implementation legislation, the better able ICWA will be to protect Indian children, their families and their tribes. III. BREATHING OUT: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE “EXISTING INDIAN FAMILY EXCEPTION” The most extreme example of resistance to ICWA by state courts and social services agencies has been the rise of the judicially-created “Existing Indian Family Exception” (“EIFE”). 30 COLO. REV. STAT. § 19-1-126(4)(a)(I)(2006); IA. ST. JUV. P. § 232B.5(10)(2003); MI. R. SPEC. P. MCR 3.980(A)(3) (2003). 31 IA. ST. JUV. P. § 232B.5(11)(2003). 32 MI. R. SPEC. P. MCR 3.980(A)(3) (2003). 33 New Mexico addressed what appears to have been an area of confusion by including a clarifying provision that, “An Indian child residing on or off a reservation, as a citizen of this state, shall have the same right to services that are available to other children of the state, pursuant to intergovernmental agreements. The cost of the services provided to an Indian child shall be determined and provided for in the same manner as services are made available to other children of the state, utilizing tribal, state and federal funds and pursuant to intergovernmental agreements. The tribal court, as the court of original jurisdiction, shall retain jurisdiction and authority over the Indian child.” N.M. STAT. § 32A-1-8(E). 34 25 U.S.C. § 1901 (2), (3). 7 The Kansas Supreme Court created the EIFE in 1982 by holding in the case In Re Adoption of Baby Boy L. that ICWA should only apply to the removal of Indian children who were members of an Indian family and participated in Indian culture.35 Courts in Kentucky, Louisiana and Missouri adopted the exception.36 Oregon and Washington courts originally adopted the exception, but both states have since statutorily rejected it.37 The courts of Alaska, Arizona, Idaho, Illinois, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, and Utah have rejected the EIFE.38 Similarly, the Iowa state legislature has rejected the exception.39 California courts are split on the issue. The first, third and fifth appellate districts rejected it.40 The second district, second division; the fourth district, third division; and the sixth appellate district have adopted it.41 Most recently, Colorado has joined the growing list of states rejecting the EIFE in the recent decision, In the Matter of the Petition of N.B,42 a case concerning a non-Indian stepparent’s petition to adopt her Indian step-son over the objection of his Indian mother. In declining to adopt the exception, the N.B. court relied on the 35 643 P.2d 168, 175-77, 231 Kan. 199, 205-09 (1982) See Rye v. Weasel, 934 S.W.2d 257, 262 (Ky.1996); Hampton v. J.A.L., 658 So.2d 331, 334-335 (La.Ct.App.1995); In Interest of S.A.M., 703 S.W.2d 603, 608 (Mo.Ct.App.1986). 37 OKLA.STAT. tit.10 § 40.3 (2001); WASH. REV. CODE §§ 26.10.034(1), 26.33.040(1). 38 See In re Adoption of T.N.F., 718 P.2d 973, 977-8 (Alaska 1989); Michael J., Jr. v. Michael J. Sr., 7 P.3d 960, 963-4 (Ariz.Ct.App.2000); In re Baby Boy Doe, 123 Idaho 464, 470-71, 849 P.2d 925, 931-32 (1993); In re Adoption of S.S., 252 Ill.App.3d 33, 42-43, 190 Ill.Dec. 802, 622 N.E.2d 832, 838-39, (1993) rev’d on other grounds 167 Ill.2d 250, 212 Ill.Dec.590, 657 N.E.2d 935 (1935); In re Elliott, 218 Mich.App. 196, 203-06, 554 N.W.2d 32, 35-37 (1996); In Re Adoption of Riffle, 277 Mont. 388, 393, (22 P.2d 510, 513-14 (1996); In re Adoption of Child of Indian Heritage, 111 N.J. 155, 169-71, 543 A.2d 925, 932-33 (1988); In re Baby Boy C., 27 A.D.3d at 46-53, 805 N.Y.S.2d at 319-327; In re A.B., 663 N.W.2d 625, 636 (N.D. 2003); Quinn v. Walters, 117 Or.App. 579, 583-84, 845 P.2d 206, 208-209 (1993) rev’d on other grounds, 320 Or. 233, 881 P.2d 795 (1994); In re Adoption of Baade, 462 N.W.2d 485, 489-90 (S.D.1990); State in Interest of D.A.C, 933 P.2d at 999-1000. 39 IOWA CODE, § 232B.5(2). 40 In re Adoption of Hannah S., 48 Cal. Rptr.3d 605, 610-11(2006); In re adoption of Lindsay, 280 Cal.Rptr 194, 197201 (1991). 41 In re Santos Y., 112 Cal.Rptr.2d 692, 715-27 (2001); Crystal R. v. Superior Court 69 Cal.Rptr.2d 414, 420-27 (1997); In re Alexandria, 53 Cal.Rptr.2d 679, 684-87 (1996). 42 --- P.3d ---, 2007 WL 2493906 (Colo.App. 2007) *5-6 (petition for cert. filed)(No.07 SC 961). 36 8 reasoning of the U.S. Supreme Court in Mississippi Band of Choctaw v. Holyfield.43 In Holyfield, the Court stated that individual reservation-domiciled tribal members having custody over children on a reservation cannot defeat the tribe’s exclusive jurisdiction over those children by removing them from the reservation.44 The Court explained that such action would defeat congressional recognition of the tribes’ interest in Indian children as well as the interests of the Indian children themselves. Id. The N.B. court, noting that several courts have read this language as undermining the exception, stated that, “We agree with this view. Just as a parent or Indian custodian cannot defeat application of the ICWA by removing a child from a reservation, a parent or Indian custodian should not be able to do so by unilaterally deciding that the Indian child will not be raised in an Indian home and will not participate in Indian culture. Both actions similarly defeat the tribal interest recognized by the statute.”45 In further support of its rejection of the EIFE, the N.B. court found that the plain language of ICWA did not require the child to be part of an existing Indian family and that applying the exception would “empower state courts to make an inherently subjective factual determination as to the “Indianness” of a particular child or the parents, which courts are ‘ill-equipped to make.’”46 The N.B. court summarily rejected the stepmother’s challenges that ICWA is unconstitutional because (1) ICWA is a racially-based statute, which does not survive heightened scrutiny; (2) the ICWA violates a child’s substantive due process right to a stable placement because that right is furthered by stepparent adoption; (3) the ICWA violates equal protection by placing demands on stepparents which do not exist under state law; and (4) the 43 490 U.S. 30 (1989). Id. at 49-53. 45 N.B. at *6. 46 Id. at *6 citing In Re Alicia, 65 Cal. App.4th at 90, 76 Cal.Rptr.2d at 128; In Re Baby Boy C., 27 A.D.3d at 49, 805 N.Y.S.2d at 324. 44 9 ICWA violates the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution because it infringes on the powers over domestic relations reserved to the states.47 The N.B. court joined the line of courts that previously rejected these arguments. The N.B. court found that the rational basis test applies and ICWA survives that scrutiny.48 Finding no precedential authority from the U.S. Supreme Court or the Colorado Supreme Court, the N.B. court declined to recognize a child’s substantive due process right to a stable home and concluded that ICWA is constitutional and does not violate the Tenth Amendment.49 The Existing Indian Family Exception does represent serious resistance to the application of ICWA and the protections that it affords Indian children, parents and tribes. On an encouraging note, with the recent Colorado N.B. decision, no state has adopted the EIFE in over a decade—since 1996. Nonetheless, ICWA practitioners may continue to hold their breath until the U.S. Supreme Court or Congress expressly rejects the EIFE.50 IV. BREATHING (LIKE A FINE WINE) REQUIRED: APPLICABILITY TO PRIVATE NONPARENT CUSTODY ACTIONS In the years since the enactment of ICWA, the child welfare landscape of the United States has changed dramatically. In 1985, 276,000 children were in foster care.51 By 1999, this 47 Id. at *7. See id. 49 Id. at *8. 50 In 1996, the Congressional bill H.R. 3286 was introduced which would have amended ICWA and codified the EIFE. The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs rejected that portion of the bill finding that the exception was “completely contrary to the entire purpose of ICWA.” S.REP.NO. 335, 104th Cong.2d Sess.14 (1996). Testimony of Thomas L. LeClaire, Director of the Office of Tribal Justice, U.S. Department of Justice Before the Senate Indian Affairs Committee (June 18, 1997) http://www.justice.gov/archive/otj/Congressional_Testimony/icwa2.fin.html. 51 Swann, Christopher A. and Michelle Sheran Sylvester, The Foster Care Crisis: What Caused Caseloads to Grow? Demography 43.2 (2006) 309-335, Population Association of America, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/demography/v043/43.2swann.html. 48 10 number had more than doubled, increasing to a staggering 568,000.52 One recent study, The Foster Care Crisis: What Caused Caseloads to Grow? revealed that the leading contributor to the rise in foster care figures was the substantial increase in the number of women incarcerated and the average length of their sentences as a consequence of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act.53 Within these burgeoning national foster care figures, American Indians make up only 1% of the U.S. populations, but American Indian children comprise 2% of the formal foster care system.54 In the 1980’s, a shortage in the number of available foster family homes prompted state social workers to turn increasingly to kin as an essential placement resource.55 One study discovered that the number of available foster homes decreased from 147,000 nationwide in 1987 to approximately 100,000 in 1990.56 It was thought that the reduction in foster homes was due to the growth of the number of single-parent households, the increasing proportion of women employed outside the home, the increase in divorce rates, and the rising costs of child rearing.57 All of these factors make it much more difficult for any family to undertake the burden of caring for additional children. Compounding the effect of the exponentially increasing number of children needing out of home care and the shrinking number of available foster homes, is the burden on the social services systems themselves occasioned by heavy caseloads and frequent turnover of child welfare caseworkers. Consequently, states are increasingly turning to grandparents, 52 Id. at 329. Id. 54 Population Reference Bureau, analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau. 2000 Census Summary File 1. As cited in: Annie E. Casey Foundation (2002). Kids Count Data Book. AECF: Baltimore, MD. 55 The Future of Children, When Children Cannot Remain Home: Foster Family Care and Kinship Care, The Growth of Kinship Foster Care, available at http://www.futureofchildren.org/information2827/information_show.htm?doc_id_=75367. 56 Id. 57 Id. 53 11 other relatives and friends of orphaned, abused and neglected children as the numbers rise. Present day, relatives predominantly provide homes for the vast majority of children whose parents can no longer care for them.58 Nearly six million children across the United States are living in households headed by grandparents or other relatives.59 Many of these relative and non-relative caregivers have obtained physical, if not legal, custody of children outside of the formal foster care system. Those caregivers outside the system who have not gained legal responsibility for a child through adoption, guardianship or other type of custody action often have trouble accessing social services and welfare programs. They may not be able to consent to medical treatment for the child, may be prevented from adding the child to their private health insurance coverage or from accessing federal health coverage for the child through Medicaid or other state-operated plans. Caregivers without a custody order may also have problems enrolling children in school. In response to this situation, as of 2005, 18 states expanded their kinship care60 programs and another 9 states had pending proposals to do the same.61 These states are making efforts to reduce paperwork, provide support services and increase funding for relative 58 Christine Vestal, States expand kinship care programs, available at http://www.stateline.org/live/. AARP Grandparent Center, Colorado: A State Fact Sheet for Grandparents and Other Relatives Raising Children, citing U.S. Census Bureau Table DP-2, Profile Selected Social Characteristics: 2000. http://ipath.gu.org/documents/A0//colorado05.pdf. (Last visited 03/03/07.) 60 “Kinship care” is a generic term that is broadly used to include formal and informal arrangements where children are living with and being raised by relatives, or even close family friends, who are not their parents. Formal kinship care arrangements apply to children reported to the child protective agency, removed from the care of a parent or guardian, and placed in state custody with the local department of social services. The department is then responsible for providing support services and supervision to the child/children while they are cared for in a kinship care placement. These children fall under the care and protection of the formal child welfare system. Informal kinship care is care provided by a relative or family friend without the involvement of the local department of social services. Often, these children have not come to the attention of the social services agency and living under an agreement among family members. All family matters are handled within the family unit. Berman, M.D., Stephen and Sara Carpenter, M.D. “Findings Brief—Children in Foster and Kinship Care at Risk for Inadequate Health Care Coverage and Access,” Changes in Health Care Financing & Organization, Vol. VII, No. 4, July 2004, ACADEMY HEALTH, p. 2. 61 Id. 59 12 caregivers. Some states, like Colorado and New Mexico, have expanded the definition of “kin” to include family friends and acquaintances who have been informally entrusted care of a child by a parent.62 Many states are also passing laws to make it easier for grandparents and other family members to gain the legal right to enroll children in school and secure their medical care.63 Over the past five years, states have begun to enact laws to make grandparents de facto guardians of grandchildren who already live with them.64 Many of the state legislative initiatives provide standing to non-parents to bring private child custody actions. Often these actions fall under the jurisdiction of the state court’s domestic relations division--not the juvenile court where child protective cases are usually filed. Although there persist problems with ICWA compliance by state child welfare agencies, these agencies are more likely to be cognizant of the law as a result of over 30 years of exposure than are private persons and domestic relations courts.65 The question arises that, if an increasing number of informal foster care placements occur under expanded kinship care initiatives and state laws that make it possible for non-parents to gain legal custody outside of child protective proceedings, who will perform the gate-keeping function for purposes of ICWA compliance without the involvement of state social services agencies? ICWA governs child custody proceedings involving Indian children. Under the Act, an “Indian child” is “any unmarried person who is under the age of eighteen and is either (a) a member of an Indian tribe or (b) is eligible for membership in an Indian tribe and is the 62 See N.M. STAT. ANN. § 40-10B-8(C)(1978); COLO. REV. STAT. § 14-10-123(2006). Id. 64 MINN. STAT. § 257.C.01.Subd. 3 (1999). 65 U.S. Government Accountability Office, Indian Child Welfare Act. Existing Information on Implementation Issues Could Be Used to Target Guidance and Assistance to States. GAO-05-290 (April 2005), 58 (GAO notes that some implementation problems with ICWA exist but scarcity of data makes it impossible to estimate how extensive the problems are). 63 13 biological child of a member of an Indian tribe.”66 “Child custody proceedings” include “foster care placements,” termination of the parent-child relationship, preadoptive placements and adoptive placements.67 For our discussion of third party private custody actions, our focus will be on the broad term: “foster care placements.” A “foster care placement” is defined as, “any action removing the Indian child from its parent or Indian custodian for temporary placement in a foster home or institution or the home of a guardian or conservator where the parent or Indian custodian cannot have the child returned upon demand, but where parental rights are not terminated . . . .”68 It must be noted that ICWA does not limit the term “foster care placement” to situations in which the Indian child is in state custody.69 In determining whether a custody case is governed by ICWA, the focus is not on what a proceeding is called, or whether it is a private action or an action initiated by a public agency, but on whether the case meets the definition of a “child custody proceeding” under the Act.70 For example, in the State of Colorado, ICWA is most likely to arise in the context of a dependency and neglect case brought under the Colorado Children’s Code, Title 19 of the Colorado Revised Statutes. Jurisdiction over dependency and neglect actions rests exclusively with the juvenile court.71 The Colorado legislature has created a separate private cause of action for the “allocation of parental rights and responsibilities” (“APR”) by which unmarried parents and certain other caretakers of children may petition to become a child’s legal 66 25 U.S.C. § 1903(5). 25 U.S.C. § 1903(1). 68 25 U.S.C. § 1903 (1)(i). 69 See N.B. at *2, “ . . . [W]e recognize that Congress enacted the ICWA to address rising concerns over the consequences to Indian children and tribes of abusive state and county child welfare practices which separated Indian children from their families and tribes through adoption by strangers. See Holyfield, 490 U.S. at 32. Nevertheless, the ICWA’s plain language is not limited to action by a social services department.” 70 RISLING, MARY J., CALIFORNIA JUDGES’ BENCHGUIDE: THE INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT, 7 (2000). 71 COLO. REV. STAT. § 19-1-104. 67 14 custodian.72 APR actions are within the separate jurisdiction of the domestic relations division of the district court.73 The division in which a custody action is brought is not determinative, however. So long as the action meets ICWA’s definition of a “child custody proceeding,” the requirements and the protections of the Act apply. States are with increasing frequency enacting statutory provisions that allow nonparents, including non-relatives, to obtain physical and legal custody over children without necessitating the need for state social services involvement. For example, in addition to Colorado’s APR provisions, Minnesota has authorized a person asserting him or herself to be a “de facto custodian”74 or “interested third party”75 to bring an action for a child’s custody. New Mexico allows a caregiver of a child to be considered “kin” and granted “kinship guardianship” if the petitioner has a relationship to the child as: 1) a relative; 2) a godparent; or 3) a member of the child’s tribe or clan.76 If the petitioner is “an adult with whom the child has a significant bond” then that individual is also consider to have a kinship relationship under the statute.77 The State of New York sets a high bar for a non-parent to hurdle before he or she may interfere with a natural parent’s right to care and custody. The non-parent petitioner must, as an initial matter, establish that the parent surrendered the child, abandoned the child, is unfit or has persistently neglected the child.78 In New York’s landmark case on non-parent custody actions, Bennett v. Jeffreys, the Court of Appeals held that a parent may not be deprived of the custody of a child unless, “. . . there is first a judicial finding of surrender, abandonment, 72 COLO. REV. STAT. § 14-10-123. COLO. REV. STAT. § 14-10-123(1), 14-10-123(d). 74 MINN. STAT. §257C.01(2). 75 MINN. STAT. §257C.01. Subd 3. 76 N.M.STAT. ANN. §40-10B-3(C) (1978). 77 Id. 78 Merritt v. Way, 460 N.Y.S.2d 20 (1983). 73 15 unfitness, persistent neglect, unfortunate or involuntary extended disruption of custody, or other equivalent but rare extraordinary circumstance which would drastically affect the welfare of the child.” 79 As of January 2004, however, things became easier for grandparents to seek custody. Under the revised New York statutes, grandparents are conferred with standing to seek custody, either in supreme court (by writ of habeas corpus or by special proceeding) or in Family Court under New York Domestic Relations Law § 72(2) and Family Court Act § 651. In order to be awarded custody rights to the child, the grandparents must demonstrate to the court that “extraordinary circumstances” exist.80 While on its face, this would seem to be a codification of the Bennett standard, the statute goes further by providing that “an extended disruption of custody” constitutes an extraordinary circumstance.81 An extended disruption of custody includes “a prolonged separation of the respondent parent and the child for at least twenty-four continuous months during which the parent voluntarily relinquished care and control of the child and the child resided in the household of the petitioner grandparent or grandparents . . . .”82 The court may find extraordinary circumstances even if the prolonged separation is less than 24 months.83 The legislature does not provide any other guidance, apart from a prolonged separation, as to what might constitute an extraordinary circumstance. In the case of Tolbert v. Scott, the Court of Appeals stated that “extraordinary circumstances” would continue to include situations where, a parent is mentally or physically unfit to have custody, where there has been a protracted separation between parent and child or “where the 79 356 N.E. 2d 277, 283 (1976). N.Y. DOM. REL. LAW § 72(2)(a) (2003) . 81 Id. 82 N.Y. DOM. REL. LAW § 72(2)(b) (2003). 83 Id. 80 16 attachment of the child to the custodian is so strong that separation threatens destruction of the child.”84 In Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico and New York, the non-parent private custody action is filed in a court or a division of the trial court that does not have jurisdiction to hear child abuse and neglect petitions. Rather these private custody actions are brought in the domestic relations division or family court, where divorces are heard. ICWA does not apply to such divorce proceedings or other custody actions between the parents so these family court judges are not likely to have much exposure to the federal law.85 Moreover, a significant concern arises in that even state case workers and juvenile court judges assigned to hear abuse and neglect cases receive little ongoing training in the application of ICWA. Private persons and family law judges handling a domestic relations docket are even less likely to be cognizant of the Act’s applicability, requirements and overall purpose of preventing the breakup of Indian families and the important separate interest of tribes in their children.86, 87 84 15 A.D.3d 493, 494, 2005 N.Y. Slip Op. 01208, citing Bennett at 550-551, Matter of Miller v. Michalski, 11 AD3d 1029 (2004), Matter of McDevitt v. Stimpson, 1 AD3d 811 (2003), Matter of Benjamin B., 234 AD2d 457 (1996). 85 See 25 U.S.C. § 1903(1), the term “child custody proceeding” “. . . shall not include a placement based upon . . . an award in a divorce proceeding, of custody to one of the parents.” 86 GAO-05-290 supra at 50. 87 This concern is lent credence by the ruling of a Denver District Court judge hearing the domestic relations docket in the case In re the Parental Responsibilities of M.S., Order dated 10/30/03, Martinez, J., No. 01DR1004 (Denver Dist.Ct). This case involved an APR petition by non-Indian grandparents regarding their grandson who was an enrolled tribal member. The district judge ruled that ICWA did not apply to the APR proceeding stating that: . . . 3. In the present case, the Petitioners who are the grandparents of the Minor Child, have petitioned the Court for allocation of parental responsibilities. They are not petitioning for termination of parental rights of the Respondents nor are they asking Social Services to place the child in Foster Care. Social Services is not involved in this case in terms of placement of the minor child. This Court further finds that the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) does not apply in this case. 17 Private third party custody actions available pursuant to state law give grandparents, other relatives and other non-parent caregivers of American Indian children a valuable means by which they may gain formal legal authority to care for these children without needing to involve the already overwhelmed social services system. These Indian children who become the subject of such private proceedings, however, are entitled to the same familial and cultural protections ensured by ICWA as are those in abuse or neglect proceedings and guardianships. In privately filed actions, there is no state social services involvement and the judges who usually adjudicate privately filed custody cases filed in the state court’s domestic relations division are likely not to be highly familiar with the provisions of ICWA. Family law practitioners handling these cases therefore may need to educate the court as why the Act applies. Diligence, in making sure that ICWA’s requirements are met in private custody actions filed by non-parent petitioners involving Indian children, is essential to ensuring that the best interests of American Indian children, their families and their Indian tribes are being met. The emerging area of private non-parent custody actions involving Indian children is one in which ICWA will need to “breathe” and hopefully, caselaw will develop or legislation enacted that acknowledges ICWA’s applicability in these situations. V. CONCLUSION 4. As stated above, this is not a termination of parental rights or foster care placement case. This is not a juvenile court proceeding. All pertinent Colorado case law involving ICWA relates to juvenile cases, not domestic cases.” (Emphasis supplied.) The presiding judge is no longer on the bench. 18 In looking back over the past 30 years since ICWA’s enactment, it appears that ICWA generally works well.88 ICWA is particularly effective when states “breathe in” and internalize the federal law into their own state children’s codes. The Existing Indian Family Exception, while an extremely troubling judicially-instigated development, thus far has been rejected by Congress and fortunately seems to be losing persuasive force among state courts. Indian children, their families and their tribes can only benefit from the EIFE’s demise. Finally, practitioners and judges need to be aware of the changing child custody landscape, which is shifting from actions brought by state social services agencies, to more and more private actions brought by non-parents. While these non-parents, may be deeply concerned about the welfare of the Indian child, it is nonetheless critically important to the Indian child’s best interest that the protections and requirements of ICWA be applied in these new contexts. 88 Leclaire, supra at note 50, at 1. 19