CHAPTER 2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK This chapter mainly

advertisement

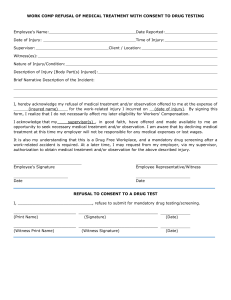

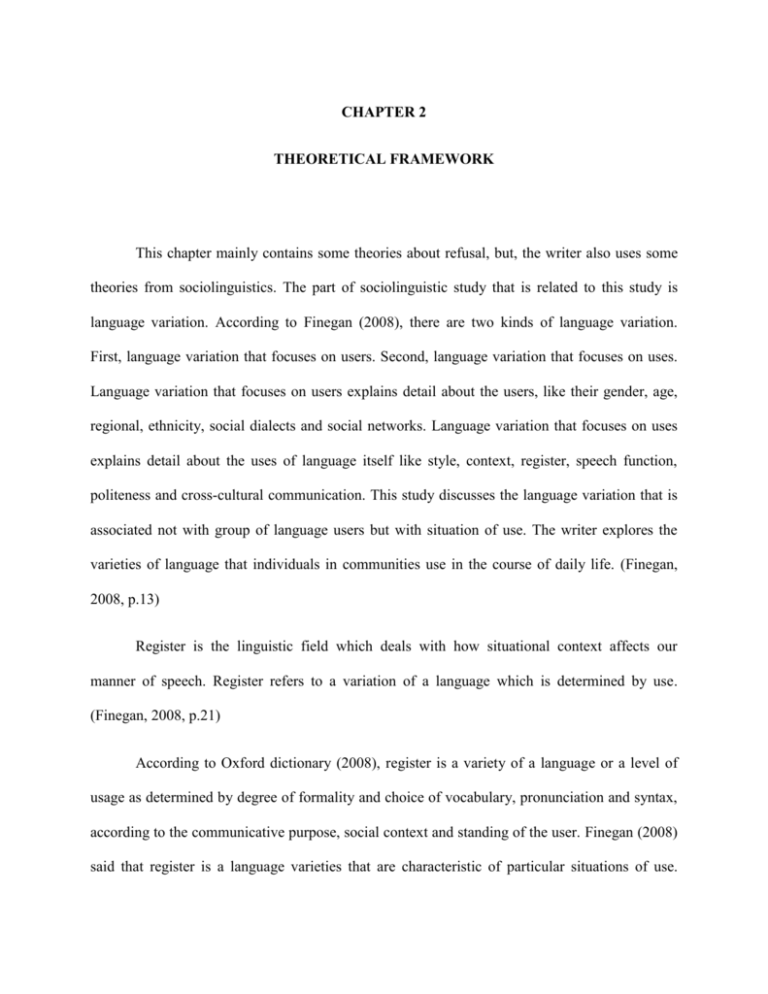

CHAPTER 2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK This chapter mainly contains some theories about refusal, but, the writer also uses some theories from sociolinguistics. The part of sociolinguistic study that is related to this study is language variation. According to Finegan (2008), there are two kinds of language variation. First, language variation that focuses on users. Second, language variation that focuses on uses. Language variation that focuses on users explains detail about the users, like their gender, age, regional, ethnicity, social dialects and social networks. Language variation that focuses on uses explains detail about the uses of language itself like style, context, register, speech function, politeness and cross-cultural communication. This study discusses the language variation that is associated not with group of language users but with situation of use. The writer explores the varieties of language that individuals in communities use in the course of daily life. (Finegan, 2008, p.13) Register is the linguistic field which deals with how situational context affects our manner of speech. Register refers to a variation of a language which is determined by use. (Finegan, 2008, p.21) According to Oxford dictionary (2008), register is a variety of a language or a level of usage as determined by degree of formality and choice of vocabulary, pronunciation and syntax, according to the communicative purpose, social context and standing of the user. Finegan (2008) said that register is a language varieties that are characteristic of particular situations of use. Registers vary along certain time and it reflects social processes. Finegan (2008) gives an example of it, people generally speak (and write) in markedly different ways in formal and informal situations. Formality and informality can be seen as opposite poles of a situational continuum along which forms of expression may be arranged. (Finegan, 2008, p.21-23) 2.1 Refusal Strategies 2.1.1 Definition of Strategy Strategy is a plan of action or policy designed to achieve a major or overall aim. Strategy is important because it is the way to achieve goals. Strategy generally involves setting goals, determining actions to achieve the goals, and execute the actions. A strategy describes how the ends (goals) will be achieved.(Freedman, 2013, p.1).The strategies in refusal can be divided into four. Those strategies will be explained one by one below. Figure1.Graphic for Strategies in Refusal (Beebe, Takahashi, Uliss-Weltz, 1990, p.61) 2.1.2 Definition of Refusal Refusing is a very common thing that happens every time and everywhere regardless age, gender, and social status. According to Oxford dictionary (2008), the meaning of refusal is an act of refusing to do something, it is an expression of unwillingness to accept or grant an offer or request from others. A refusal is a negative response to an offer, request, invitation and suggestion. It is often difficult to reject requests, misunderstandings may arise if someone does not carefully choose the right words to refuse. Refusals are face-threatening acts, the refusals function as a response to an initiating act and are considered a speech act by the refuser fails to engage in an action proposed by the speaker. (Hassani, Dastjerdi, Mardani, 2011, p.37) From a sociolinguistic perspective, refusals are important because they are sensitive to social variables such as gender, age, level of education, occupation, power, and social distance (Fraser, 1990, p.219).Refusal is one of the speech acts in which communication problems are likely to happen. Refusals are negative responses to requests, invitations, suggestions, offers, and the like which are frequently used in our daily lives (Sadler & Eroz, 2001, p.55). Refusals are very important because of their communicative role in everyday social interaction. Generally speaking, how to say “no” is more important than the answer itself. 2.1.2.1 Sequence of Refusal As Hassani, Dastjerdi, and Mardani (2011, p.39) mentioned, the usual sequence in refusal strategy application is in three phases: - Pre-refusal strategies: preparing the addressee for an upcoming refusal; - Main refusal (Head Act): bearing the main refusal; - Post-refusal strategies: functioning as emphasizer, mitigator or concluder of the main refusal. For example, a refusal sequence of someone to his friend’s request for going to movies together would be: Uhm, I’d really like to (pre-refusal), but I can’t (main refusal). I’m sorry. I have a difficult exam tomorrow (post- refusal). The number of moves in a refusal depends on the type of refusal (that is, whether it is direct or indirect). (Hassani, Dastjerdi, Mardani, 2011, p.40) Compare the following examples: A: May I go out now? B: No, you may not. A: Have another cookie. B: Thanks. Everything was so tasty, I couldn’t eat another bite. As it can be seen, there is only one move in the first example of refusal. On the contrary, the person uses more than one move in indirect refusals. Therefore, indirect refusals have more moves to make a refuse. 2.1.2.2 Types of Refusal Beebe, Takahashi, and Uliss-Weltz (1990) point out that refusal is a complex speech act which requires a high level of pragmatic competence to be performed successfully. The important point is that indirect strategies should be used to eliminate the offense to the hearer. Furthermore, Beebe, Takahashi, and Uliss-Weltz (1990) classify refusals into two main groups: direct refusals and indirect refusals. Direct refusals relate to the fact that the speaker expresses his/her inability to conform using negative propositions including performatives such as “I decline” and non-performatives like “I can’t” or “no”. Indirect refusals indicate the fact that an offer, an invitation, or a request is indirectly declined. Indirect refusals include different types: 1. Statement of regret: “I’m sorry.” 2. Wish: “I wish I could help you.” 3. Excuse, reason, explanation: “I have an exam.” 4. Statement of alternative: “I can do X instead of Y.” 5. Set condition for future or past acceptance: “If I had enough money, …” 6. Promise of future acceptance: “I’ll do it next time.” 7. Statement of principle: “I never drink right after dinner.” 8. Statement of philosophy: “One can’t be too careful.” 9. Attempt to dissuade interlocutor: 9-1. Threat or statement of negative consequences to the requester: “If I knew you would judge me like this, I never did that.” 9-2. Criticize the requester: “It’s a silly suggestion.” 9-3. Guilt trip (waiter to customers who want to sit for a while): “I can’t make a living off people who just order tea.” 10. Acceptance functioning as a refusal: 10-1. Unspecific or indefinite reply: “I don’t know when I can give them to you.” 10-2. Lack of enthusiasm: “I’m not interested in diets.” 11. Avoidance: 11-1. Non-verbal (silence, hesitation, doing nothing and physical departure) 11-2. Verbal (topic switch, joke, repetition of past request, postponement and hedge); An example for postponement can be: “I’ll think about it.” The above classification is used in current studies on refusal speech act. There are also some adjuncts to the refusals as follows: 12. Statement of positive opinion: “That’s a good idea.” 13. Statement of empathy: “I know you are in a bad situation.” 14. Pause fillers like “well” and “uhm” 15. Gratitude/appreciation: “Thank you.” The main reason of using indirect refusal is to sound more polite, so, when someone refuse other people, the person doesn’t get offended or misunderstood by the refuser because when using indirect refusal people say words like “I’m sorry” or “I wish I could help” which sound a lot nicer than saying “no” or “I can’t” right away. However, it does not mean that people who use direct refusal is not a nice person, not polite or arrogant, while many of them might be arrogant or less polite, most of them might just have this kind of way of talking or refuse, and some people might find it offensive and spiteful. (Beebe, Takahashi, Uliss-Weltz, 1990) 2.1.2.3 Refusal to Apologize Tyler G. Okimoto, Michael Wenzel and Kyli Hedrick (2013, p.22-31) reported on what they've found happens in people's minds when they refuse to apologize. They find that parents who tell their kids that saying sorry will make them feel better is not the whole truth. The researchers said, "We do find that apologies do make apologizers feel better, but the interesting thing is that refusals to apologize also make people feel better and, in fact, in some cases it makes them feel better than an apology would have”. (2013, p.22-31) The researchers surveyed 228 Americans and asked them to remember a time they had done something wrong. Most people remembered relatively trivial offenses, but some remembered serious offenses, including crimes such as theft. The researchers then asked the people whether they had apologized, or made a decision not to apologize even though they knew they were in the wrong. And they also divided the people at random and asked some to compose an email where they apologized for their actions, or compose an email refusing to apologize, and the result is more people decided not to apologize even when they know they were wrong. In both cases, the researchers said, refusing to apologize provided psychological benefits, which explains why people are so often reluctant to apologize. The researchers said, "When you refuse to apologize, it actually makes you feel more empowered. That power and control seems to translate into greater feelings of self-worth". Ironically, the researchers said, people who refused to apologize ended up with boosted feelings of integrity. (Okimoto, Wenzel, Hedrick, 2013, p.22-31) 2.1.3 Politeness Politeness, in an interaction, can be defined as the means employed to show awareness of another person’s face. In this sense, politeness can be accomplished in situations of social distance or closeness. (Yule, 1996, p.60) Politeness in speech is described in terms of positive and negative face. Positive face refers to one's desire to be liked and admired, while negative face refers to one's wish to remain autonomous and not to suffer imposition. Both forms, according to Penelope Brown and Stephen C. Levinson (1978), are used more frequently by women whether in mixed or single-sex pairs, suggesting for Brown a greater sensitivity in women than have men to face the needs of others. In short, women are to all intents and purposes largely more polite than men. (Brown and Levinson, 1978, p.38) Techniques to show politeness:(Beebe, Takahashi, Uliss-Weltz, 1990, p.61) Expressing uncertainty and ambiguity through hedging and indirectness. (e.g. “I have an exam”, “If I have enough money, …”) Polite lying. Robert Feldman (2010, p.29) cites self-esteem as one of the biggest culprits in our lying ways: "We find that as soon as people feel that their self-esteem is threatened, they immediately begin to lie at higher levels." Feldman believes many lies are simply for the purpose of maintaining social contacts by avoiding insults or discord. Small lies that avoid conflict are probably the most common sort of lie...and avoiding conflict is a top motivator for deception. For example: someone is lying about traffic holding them up, rather than sleeping in... or a "no, you look great in those pants" -- both sorts of lies achieve the effect of avoiding social conflict. They are "make life easier" kinds of lies. 2.1.4 Language and Gender Language and gender is an area of study within sociolinguistics, applied linguistics, and related fields that investigates varieties of speech associated with a particular gender, or social norms for such gendered language use. According to Lakoff’s (1975, p.37) study have shown that women are more likely to use politeness formulas than men, though the exact differences are not clear. Most current research has shown that gender differences in politeness use are complex, since there is a clear association between politeness norms and the stereotypical speech of middle class white women, at least in the UK and US. It is therefore unsurprising that women tend to be associated with politeness more and their linguistic behaviour judged in relation to these politeness norms. (Lakoff, R., 1975) 2.1.5 Self-disclosure Men tend to communicate differently with other men than they do with women, while women tend to communicate the same with both men and women. Female tendencies toward self-disclosure, i.e., sharing their problems and experiences with others, often to offer sympathy, contrasts with male tendencies to non-self disclosure and professing advice or offering a solution when confronted with another’s problems.(Dindia, K. & Allen, M.,1992)