The Pope is Wrong on Rights

advertisement

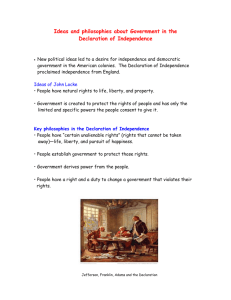

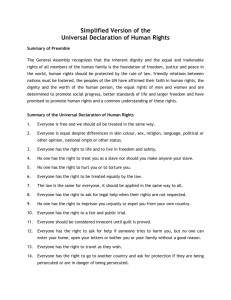

The Pope is Wrong on Rights By Stephen Pidgeon April 18, 2008 Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.1 Today Pope Benedict XVI addressed the U.N. General Assembly. During the course of this address, on the 60th anniversary year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Pope made many statements concerning the nature and origin of human rights, the values supported by these rights, and their ultimate pragmatic application, which of course, included reference to the right of the Catholic Church to have a meaningful effect on the dynamic properties of the emerging sociological and political paradigm in the modern context. The Pope, however, is wrong on human rights; dangerously wrong. Let us consider his assertions, one by one. First, the Pope gives credence to the Universal Declaration, saying that the “document was the outcome of a convergence of different religious and cultural traditions, all of them motivated by the common desire to place the human person at the heart of institutions, laws and the workings of society, and to consider the human person essential for the world of culture, religion and science.”2 This claim infers the intent “to place the human person at the heart of institutions, laws and the workings of society, and to consider the human person essential for the world of culture, 1 Article 18, Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted and proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948. 2 Text of pope's U.N. speech … motivated by the hope drawn from the saving work of Jesus Christ'. April 18, 2008, WorldNetDaily, http://www.wnd.com/index.php?fa=PAGE.view&pageId=61975 religion and science,” to those who developed this Declaration, which is simply not accurate or historically correct. According to the United Nations Association in Canada, the Charter was created primarily to avoid a recurrence of the horrors experienced during World War II. The Universal Declaration started out as a roster of prohibitions on the actions of the state in order to prevent the repetition of the atrocities perpetrated by the Nazi regime in Central Europe. It would have helped if the drafters of this Declaration had first declared and defined what those atrocities were. The Pope goes on to say that “the rights recognized and expounded in the Declaration apply to everyone by virtue of the common origin of the person, who remains the high-point of God's creative design for the world and for history.”3 This claim extrapolates an origin not consistent with actual application. The Pope tries to claim that “the high-point of God’s creative design for the world and for history” – “the common origin of the person” is the source of universal application of rights. In a word or two, this is wishful thinking. The application of the “rights” set forth in the Universal Declaration is predicated exclusively upon the degree of the sovereignty ceded to the international authority by the sovereign nation-states, and, as the world has witnessed since the adoption of this Declaration, these “privileges” exist only to the degree that sovereignty has actually been ceded. As a matter of international law, the Declaration itself has not been signed by any nation, and is not legally binding on any nation state. It is essentially merely a “here, here!” As a matter of practical reality, then, the roster of “privileges” set forth in the Universal Declaration apply to no one, because not one nation on earth has ceded even an ounce of sovereignty to this Declaration. Nonetheless, the Pope goes on to interpolate that the “privileges” set forth in the Universal Declaration “are based on the natural law inscribed on human hearts and present in different cultures and civilizations.”4 Again, the Pope projects his aspirations onto this document when such aspirations are simply not present. Traditionally, the “natural law” has meant the law as set forth in the Mosaic texts of the Old Testament or Torah. I am confident that this is the body of natural law to which the Pope refers, but it is possible that I have misconstrued his intent. Other interpretations would count “general revelation” as the source of natural law – that is, things “self-evident” such as reason and conscience (although, “general revelation” means in respect of a Godly order within metaphysics). In review of the Preamble of the Declaration, it is possible to distinguish “natural law” from the self-proclaimed source of the “privileges” set forth in the UD. For instance, the source of freedom, justice and peace in the world is declared to be the “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family”5 (although the UN is pushing to extend this “rights” to apes as well). The plain meaning of this phrase is that freedom, justice and peace in the world exist only when the international family of governments so recognize them. If this is true, what is created as a matter of international law is merely a group of “privileges” whose mortality is dependent upon the will of the governing class. Rights which spring from “natural law” have an existence that presupposes the will of the state. This presupposition – the Godly ordinance – is the foundation of rights. The recognition of such rights by the international family of governments, or by any single governing class, is merely an expedient set of “privileges” which may or may not give full birth to naturally ordained rights. To further understand this aspect of “natural law” it is necessary to include as a directive “special revelation” or the Word of God. The foundational doctrine for fundamental human 3 4 Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. rights springs from that Decalogue we refer to as the Ten Commandments. This roster of duties and prohibitions as ordained by God creates the supernatural authority for human rights. Such a notion is anathema to the secular state, and the spiritually blind will not recognize its ordinance. However, consider the alternative first paragraph to the UD. Whereas the God-ordained purpose of life and the God-ordained value of all human life and all indicia of human life as set forth in the inspired Word of God found in Holy Scripture is the foundation of all human rights including freedom, justice and peace in the world . . . That’s a bit different, and has substantially different consequences as its application evolves within the governing class, because every human being – including each of the unborn – has these rights whether or not governments recognize them. It seems to me that this notion would necessarily be rejected by an organization attempting to establish its power and authority; and the attempt as set forth in the Universal Declaration appears to be one anathema to the Godly order, or as we in the theological world are wont to say – unrighteous. It is alarming, then, that the leader of the self-proclaimed universal (that is to say, Catholic) church would pay homage to a creed that asserts itself over the authority of God. Again referring to the Pope’s claim that the UD springs from “natural law,” the second paragraph of the Preamble goes on to decry “barbarous acts” which have “outraged the conscience of mankind.”6 Of course, these “barbarous acts” go undefined, which is a shame, because it is difficult to determine if the General Assembly is decrying the massacre of tens of millions under the regime of Chairman Mao, the massacre of tens of millions under the Soviet regime of Josef Stalin, the Holocaust and the slaughter of millions of non-combatants by the 5 Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, op. cit. 6 Nazi regime, the ruthless execution of authority by the Empire of Japan, the steps taken by the United States to secure victory in World War II, or just all of the deaths – combatant and noncombatant – associated with World War II. I suppose one could guess that there was some hint that the Soviet deaths were decried, given the abstention by the Soviet Union in the vote among the General Assembly in its adoption of the UD. The authors of the UD also fail to define the conscience of mankind that is so outraged. The “conscience of mankind” appears to exclude the Leninist-Marxist communist conscience, and, given the abstention of Saudi Arabia, appears to exclude the Islamic conscience as well. The “conscience of mankind” identified in the UD is merely the author’s conception of such a conscience, which, given the text of the document, appears to be some undefined blend of denominational Christianity or Deism, state socialism, and secular humanism. Viewing this doctrine in a light most favorable to the authors, let us assume that waging of war itself constitutes the barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind (although such an outrage would have been impossible to express if the Axis powers had prevailed). Such an assumption begs the question initially asked by Patrick Henry: “Is life so dear, and is peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” Apparently, the authors of the UD wanted the freedoms which rose from the ashes of victory over Nazism, Japanese Imperialism and European Fascism, claiming another reason why the UD was adopted; because the victors from WWII “proclaimed” freedom of speech, freedom of belief, and “freedom from fear and want” to be the “highest aspiration” of “the common people.”7 In short, the “natural law” here is premised upon the circular reasoning that such rights exist because “the common people” have proclaimed them. 7 Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, op. cit. So far, there is no referral to general revelation as the source of natural law. In the first two paragraphs of the Preamble to the UD, the foundation for the “rights” enumerated thereunder is the self-proclaimed power of the international family of nations to declare such “rights” and the will of the “common people” to proclaim such “rights.” Neither of these two sources have sufficient authority to declare human rights, nor do these claims constitute “natural law.” Let’s consider the third source for the “rights” set forth in the UD: Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law . . .8 Now we have a claim to authority based on pragmatism; the recognition of “human rights” by the rule of law is “essential” if man (and for the feminists reading this, “man” is a euphemism for all members of the human race, male and female) is to have recourse other than rebellion to deal with oppression and tyranny. The Pope himself decries this understanding, saying that “[w]hen faced with new and insistent challenges, it is a mistake to fall back on a pragmatic approach, limited to determining “common ground,” minimal in content and weak in its effect.”9 The pragmatic expression that the recognition of rights is necessary to avoid rebellion is a notion the Pope describes and “minimal in content” and “weak in its effect.” Well said. Pragmatism is not a foundational premise a priori. It is a justification a posteriori. Besides, how useless would it be to establish a protocol for the abolition of war only to create a condition for the rise of barbarous rebellion? 8 9 Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, op. cit. Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. The next “natural law” upon which this declaration of rights is premised is the need to promote friendly relations among the nations.10 This is sentiment, not foundational natural law. Sensing this, the authors then provide us with a faith statement, claiming that “the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women.”11 Once again, this is not a foundational premise underscoring human rights. The claim is essentially circular logic: we have human rights because we have faith in human rights . . . whatever they may happen to be. Furthermore, just what exactly is meant by “the dignity and worth of the human person”? One supposes that this expresses the sentiment that there is no justification recognized (yet) by the international family of governments and the common people for genocide (the Soviet Union and Saudi Arabia abstaining). The foundational premise for human dignity and worth is simply not forthcoming. Finally, human rights are premised upon the faith of the authors in the equal rights of men and women. So far, the “natural law” upon which the UD is based is the declaration of the international family of governments, the proclamation of the common people, the necessity to create the rule of law in order to stop rebellion, and faith in equal human rights and human dignity, although we don’t know what rights and dignity actually are. Based upon this complete failure to develop any foundation for the “rights” supposedly established, declared and proclaimed in this Universal Declaration (the Communist world and the Islamic world abstaining) other than the declaration and the proclamation itself, predicated on the faith in these undefined statements concerning the human condition, the General Assembly resolved then to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, universal 10 11 Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, op. cit. Preamble, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, op. cit. respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and a common understanding of these rights and freedoms. Unfortunately, we do not know the source of the ethics behind this so-called non-binding and non-universally adopted Universal Declaration. Instead, we are left to surmise such ethics from the terms themselves. To summarize, there is no “natural law” foundation for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights set forth within the document, whether sacred or secular. There is only a bald claim of authority. As such, the statements of the human condition enumerated under the UD are merely persuasive authority delineating privileges which may be granted by the member nationstates to the UN, and nothing more. The failure to state a natural law foundation for these socalled “rights” and the non-binding aspects of the UD means that the Universal Declaration most assuredly does not set forth “human rights”; in fact, it doesn’t even set forth “human privileges.” The Pope’s claim that the “the rights recognized and expounded in the Declaration” . . . “are based on the natural law inscribed on human hearts and present in different cultures and civilizations,”12 is simply belied by the text of the UD itself. The truth is that the “rights” recognized and expounded in the Declaration are based on the self-proclaimed authority of the General Assembly, the proclamation of the common people according to the authors, the need for an international rule of law to deter rebellion, and faith in human rights generally. There is no alliteration of “natural law” anywhere in the document. The Pope then goes on to claim that “the life of the community, both domestically and internationally, clearly demonstrates that respect for rights, and the guarantees that follow from them, are measures of the common good that serve to evaluate the relationship between justice and injustice, development and poverty, security and conflict.”13 This argument is again an 12 13 Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. argument based in pragmatism: the respect for human rights is good because it allows justice, relief from poverty, and security to be evaluated. The proper understanding of human rights is an understanding founded upon an acceptance that the source of human rights is divine ordination only. The respect for Godly-ordained human rights is best evaluated in terms of righteousness – that is, a nation-state which recognizes the rights established by means of special revelation. (This roster is not ambiguous, and it is substantially different than the advisory privileges set forth in the UD). A proper theological understanding of rights would therefore assert that the life of the community, both domestically and internationally, demonstrates righteousness when it respects God-ordained rights, and the guarantees that follow from them. Righteousness is the proper measure of the common good, and righteousness establishes justice over injustice, development over poverty, and security over conflict. It is therefore the duty of the state, both domestically and internationally, to seek righteousness. While I welcome the Pope’s proclamation that “the promotion of human rights remains the most effective strategy for eliminating inequalities between countries and social groups, and for increasing security,” again we have the pragmatic argument: i.e., the promotion of human rights is the proper thing to do, because it is an “effective strategy for eliminating inequalities,” and so forth. Because the Pope has adopted a pragmatic argument concerning human rights and has ignored the supernatural foundation of rights, we do not get the defense of human rights rising from Divine ordination; instead we get a defense which measures the current roster of advisory privileges in accordance with its ability to eliminate inequality and to increase security, neither of which are human rights. (On a side note, such claims are consistent with Catholic theology which promotes the tradition of the church to an equal status with scripture, premised upon the questionable claim of apostolic succession). The promotion of supernaturally-ordained human rights is the duty of the state first and foremost. There is no God-ordained right to steal the property of others in order to distribute the stolen goods to selected classes chosen on the basis of some notion of “equality.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that each person on earth has a “right” to social security,14 to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favorable conditions of work, to protection against unemployment,15 to equal pay for equal work,16 to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection;17and to rest and leisure, including . . . holidays with pay.18 Since the international family of governments and the common people had the stage, they might as well vote themselves the wealth of the productive class. Under the UD, “human rights” also include rights “to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control”;19 and special care and assistance for motherhood and childhood.20 Nowhere in the Universal Declaration is there a right to be free from the confiscatory taxation that would be required to pay for such cradle-to-grave socialism. By supernatural ordination, however, we have a right to be free from theft, to be free from interference with the 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 22 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 23(1) 16 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 23(2) 17 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 23(3) 18 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 24 19 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25(1) 20 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25(2) 15 ownership of our property, and free from interference with our employer/employee relationships. Somehow, these rights are conveniently missing from the UD. Notwithstanding the design of the Universal Declaration to redistribute wealth by means of confiscation from the productive to the non-productive, the Pope continues to embrace this doctrine. “The merit of the Universal Declaration is that it has enabled different cultures, juridical expressions and institutional models to converge around a fundamental nucleus of values, and hence of rights,” says the Pope.21 As a matter of fact, this statement is again wishful thinking. Human trafficking and slavery are at an all-time high worldwide. The 1.5 billion people living in China do not have a free right to Christian worship; free religious expression is culturally abolished throughout the Islamic world, a world that includes around 1.3 billion people; Christians are routinely persecuted among the 1 billion Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists living in India, and the Christians living in Canada have been deprived of virtually every religious right set forth in the Universal Declaration. In the west, Catholics suffer discrimination in Orthodox nations, and Protestants are still considered cults in Catholic nations in Europe and throughout Latin America. What convergence is the Pope discussing? The Pope goes on to say: “The Universal Declaration, rather, has reinforced the conviction that respect for human rights is principally rooted in unchanging justice, on which the binding force of international proclamations is also based.”22 Once again, there is nothing in the UD itself which lends credence to this claim. There has been no unchanging justice in the history of man other than Godly justice, and the UD makes no link to Godliness or righteousness. Instead, the UD is merely the advisory, non-binding, opinion of a self-elevating institution and an author claiming to speak for common people worldwide (the communist world and the 21 22 Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Islamic world abstaining). Maybe the Pope is referring to the victory of the Allied Forces over the Axis in WWII, or victors in general (to the victors go the spoils). Even though I believe that the victory of the Allied Forces of the Axis was a victory of righteousness and an expression of God’s justice, man’s victories in war do not amount to justice, unless you are prepared to argue that the ends justify the means. This statement strikes me as an implicit yielding of authority to the international family of governments. Let’s get to the meat of the subject, shall we? The Pope is fundamentally wrong on human rights when he makes the following statement: “Since rights and the resulting duties follow naturally from human interaction, it is easy to forget that they are the fruit of a commonly held sense of justice built primarily upon solidarity among the members of society, and hence valid at all times and for all peoples.”23 Human rights (which are by definition, supernaturally ordained rights, or as Thomas Jefferson referred to them, “God-given”) do not follow naturally from human interaction. Sin follows naturally from human interaction. How did Paul put it? And even as they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a reprobate mind, to do those things which are not convenient; Being filled with all unrighteousness, fornication, wickedness, covetousness, maliciousness; full of envy, murder, debate, deceit, malignity; whisperers, Backbiters, haters of God, despiteful, proud, boasters, inventors of evil things, disobedient to parents, Without understanding, covenant breakers, without natural affection, implacable, unmerciful: Who knowing the judgment of God, that they which commit such things are worthy of death, not only do the same, but have pleasure in them that do them.24 23 24 Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Romans 1:28-32. The Pope is tangentially wrong that rights are “the fruit of a commonly held sense of justice built primarily upon solidarity among the members of society.”25 Rights do not exist as a result of the solidarity among the members of society. This is the very definition of the source of privileges. If the Pope is going to make such a claim, he cannot espouse the doctrine of sola scriptura, or even immutable truth. Instead, there is only the transient whim of a given society’s commonly held sense of justice, which sometimes includes the extermination by force of socalled inferior races. Rights, to be rights, must have supernatural authority. Grants of additional authorities and freedoms from ultimate totalitarianism from governments, societies, and other people are privileges, not rights. The Pope’s failure to recognize the sovereign authority of God in the demarcation of human rights is alarming, given his position within the Catholic Church. Finally, the Pope’s claim that human rights are “the fruit of a commonly held sense of justice built primarily upon solidarity among the members of society and hence valid at all times and for all peoples”26 is a logical disconnect which cannot be substantiated with empirical data. There is no solidarity among all peoples. There is no common language, no common body of (binding) law, no common legislature, no common church, no common religion, no common currency, no common mores, and no common politics. Furthermore, there is no commonly held sense of justice. Europeans are opposed to the death penalty for any offense. Muslims sentence adulterers and homosexuals to death. The United States protects free political speech, while China imprisons people for publicly espousing the truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Where is this fruit of a commonly held sense of justice? The Pope’s understanding of human rights is a misunderstanding, and his praise for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights cannot be substantiated by a fair read of the document 25 26 Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. Text of pope's U.N. speech, op. cit. itself, which makes no claim to a foundation of “natural law.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is in reality the Advisory Declaration of a Majority of the UN General Assembly as to Government Granted Privileges. The Pope’s praise is misplaced, because, simply put, the Pope is Wrong on Rights.